Interview Patrick Kasingsing

Images Hassell and Ar. Razvan I.Ghilic-Micu

Editor’s note: This conversation with Ar. Razvan I. Ghilic-Micu was held during the 2025 Manila Interior Design Summit (MIDS), organized by the Philippine Institute of Interior Design (PIID). Kanto thanks the PIID for making this interview possible.

Hello Razvan, welcome to Kanto! For our conversation today, we’ll be talking about the values you champion as an architect, writing and critique of built space in Southeast Asia, and where you see tomorrow’s architects headed as a mentor in the academe.

But let’s begin with your work for Hassell. Hassell’s work often champions the subtle brilliance of the anti-iconic urban grain, the ordinary structures that give neighborhoods their character. In cities like Manila, where GFA metrics usually dominate development logic, how do you make a case for the kind of regenerative architecture Hassell advocates? Regenerative architecture doesn’t always appeal to developers still chasing novelty and icons. Do you use particular design arguments, toolkits, or storytelling tactics to reframe what value looks like? How do you communicate that value to them?

Ar. Razvan I. Ghilic-Micu, senior associate, Hassell: Hey there! You started with a tough one!

The topic of value is central. Historically, architecture and development have been measured almost entirely in monetary terms: cost, dollars, and cents, because those are easy to quantify. But increasingly, new parameters are entering the picture and disrupting business as usual. By that I mean sustainability metrics, some self-imposed, others mandated by governments.

For example, large firms in Singapore already have to declare their Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3 emissions. At a minimum, governments are setting 2030 and 2050 targets. These become very objective arbiters, and you either hit them or you don’t.

I was telling Carla (Leonor, Events Lead for the Philippine Institute of Interior Designers) last night that I spend a lot of time reading the sustainability reports of our clients. You have to understand what matters to them, what drives them, and how we, as architects, can enable them to move forward quickly toward those targets.

So when we talk about challenging “business as usual,” I don’t see it as stubbornness or authorship. It’s a shared responsibility toward cities, the planet, and the clients who develop these buildings. Our role is to help them exceed their goals in a positive way.

That changes the mindset. For too long, I’ve heard questions like, “How do you convince your clients?” But I don’t see myself in the business of convincing. I see it as partnering with like-minded people. Sometimes we disagree, but at the end of the day, our role is to advise clients in their best interest.

I see. But inevitably, that must mean saying no sometimes, right? Because you said you want to work with like-minded partners, and being an architect carries its own responsibilities. You’d want to collaborate with people who share that.

Ghilic-Micu: Broadly speaking. That has to become part of the decision-making process for all ethical, responsible practices. Before you sign on to a pitch or a project, you need a robust process to understand what the work will entail.

Yes, and what you’re really getting yourself into.

Ghilic-Micu: Right. And it goes beyond “Will this be a fun design to do?”; It’s about the impact of that project. Does the client have the potential—or even just the desire—to push boundaries?

It’s also not about discrimination. Many clients have good intentions but haven’t yet worked with an architect who can help them amplify those intentions. So it’s a balancing act.

Take a few years back: two large global practices pulled out of Architects Declare. The debate was over whether designing airports in parts of the Middle East aligned with the charter. I don’t think the point is to vilify anyone. The point is to hold up a mirror and ask where you, as a practice, draw the line.

For instance, would it be responsible to design the next huge mine that depletes natural resources? Architects have to reflect on their values, their responsibilities to people and the planet, and decide which projects to undertake. And sometimes, projects that look problematic at first can be transformed, from carbon-heavy and extractive, toward neutral or even positive outcomes.

Right. And it’s not impossible. Okay, second question—and I’ll go easier this time.

You’ve been shaped by three very different regions: Europe, Asia, and America, each with its own spatial philosophy. In this age of blurred cultural identities and transnational aesthetics, how has that experience informed your approach to design? How do you create spaces that feel rooted but still responsive? And how important is it today to design architecture that is truly of its place?

Ghilic-Micu: Great question. I was born and raised in Romania, which shaped my childhood and teenage years. Later, I moved to Canada with my family, did my undergrad there, lived in the U.S. for grad school, and I’ve been living in Singapore for the past 12 years, where I’m licensed and very fortunate to have been embraced by the local community. That’s important to me on an emotional level.

Now, globalization, and the “international style” of architecture practiced over the past 70 years, has flattened the world. Buildings like the Seagram Building and Lever House set a precedent. A book I value, Unless by Kiel Moe, unpacks the Seagram Building’s carbon footprint. It shows how a single building designed in the international style mindset can have planetary-scale consequences, from where stone was mined to how far materials were shipped.

For centuries, architecture was local or regional. Materials, manpower, and resources all came from within a tight radius. Compare that to now, when we ship things halfway around the globe. The result is that cities look more and more alike. Show people a picture of a generic CBD streetscape and it’s often hard to tell: are you in Toronto, Singapore, Manila, or Tokyo?

But the consequences go beyond aesthetics. There are energy and carbon costs too.

Back to your question: living these “different lives”—Romanian, Canadian, American-educated, Singapore-licensed—has given me humility and perspective. It’s taught me that design must be rooted in its context.

At Hassell, we have a Reconciliation Action Plan in Australia that creates better outcomes together with First Nations People. That awareness reshapes the design process. Your design DNA—mine is largely Western—gets challenged and rewired. You start to design with the natural patterns of Country: water, land and sky.

Architects need to understand: when you cross a border, you’re in someone else’s home, on someone else’s land. You can contribute, but you can’t assume your value is absolute everywhere. The way I work in Singapore isn’t the way I’d work in Manila or Sydney. I have to defer, listen, walk in your shoes to design in a way that’s meaningful and respectful.

Indeed. Let me follow up. Since your creative process is so rooted in research, can you walk us through how you localize your approach? Say you have a project in the Philippines: what does that process look like? Who do you involve?

Ghilic-Micu: We start every pitch and project with a deeper appreciation of context, not just the site area on a Google map, but through our regenerative design framework, understanding carbon, ecology, and social systems.

That means a lot of research: understanding the client, their stakeholders, and even their stakeholders’ stakeholders. Any design decision ripples downstream, and you need to know how.

The first step is always to team up with a strong local partner to find answers together. Sometimes being a local means you take things for granted; you don’t question certain assumptions because “that’s just how things are.”

We all have blind spots.

Ghilic-Micu: That’s right. And on the flip side, there are unspoken cultural rules that you must be sensitive to. That’s why combining a global lens with local understanding is so important. The distance allows you to respectfully challenge assumptions, while local partners help you ground the design in reality.

So the process is about building the right team, doing broad research, and layering perspectives until you fully understand the parameters that will shape the project.

That makes sense. Let’s bring it back to Singapore, where you’re based. Singapore is often praised as a model for urban planning and architectural innovation. But some visitors would beg to differ, describing Singapore as lacking the texture, grit and soul you find in more chaotic cities like Bangkok or Hanoi. As someone who’s worked and lived in the Garden City for a while, what’s your prognosis?

And I guess, as Hassell, what do you think are some of the low-hanging fruits or opportunities for architects to either integrate or contribute to urban texture? Where does architecture’s role begin and end?

Ghilic-Micu: That’s a lovely nesting doll of a question! Three in one! I’ll try to riff with it. First, to those who call Singapore “boring.” Just this morning I watched a clip of Prime Minister Lawrence Wong addressing that exact point. In his speech, I think Prime Minister Wong even used the exact word “boring.” But he was pointing to something important: Singaporean life promotes safety, predictability, and stability. I’d be cautious about labeling Singapore with a broad brush. Beneath the international veneer, well-planned, well-articulated, predictable, “boring,” however you frame it, there is texture, history, and life. And it’s not hidden.

I’d invite those who feel otherwise to step out of the CBD, which, by the way, is a wonderful district around Marina Bay. But head to the industrial areas now being reclaimed by creative brands, or the older, grittier neighborhoods that are being preserved and carefully restored without full-on gentrification. Talk to Singaporeans in the heartlands. Everyday life there isn’t what you see on postcards. It’s real, vibrant, beautiful and deeply diverse.

So, Singapore is so much more than its CBD on postcard images. Planning makes that possible. But you also have to consider the country’s trajectory: it had almost no natural resources to begin with, only its people.

To attract investment and build a successful country, it had to show administrative strength. One anecdote I love: one of the earliest investments was the road from the airport to the city. It takes decades to build a city, but you can create a tree-lined highway in months. That display of order and ambition mattered.

Nearby countries—Malaysia for instance, where my wife is from—have rich land and resources. They didn’t face the same pressures to be frugal or intentional, and they also don’t have the advantage of Singapore’s small, manageable scale. Policies here can be implemented and felt immediately. So yes, there are pros and cons.

Other countries in the region, like the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, are full of culture, subculture, and land. But with size and abundance comes unpredictability. There’s no perfect model. Within its constraints, Singapore developed something that works remarkably well.

Now, as a practice, how do we plug into that? We know we’re global, but many of us in the Singapore studio have been there a long time, licensed there, embedded in the community. It comes back to values. Context, people, climate, beauty, these are the regenerative principles we work with. It’s not about our respective passports but an alignment of values. And in that sense, our practice and Singapore as a society are highly compatible. That’s why we see Singapore as a home base from which we can engage with Southeast Asia more broadly.

Carla Leonor, Executive Director for Events, PIID: Does Singapore have a long-term plan to stay on this course?

Ghilic-Micu: Yes, there are 2030 and 2050 targets. The new 2025 master plan has just been released. It’s a constant work in progress: long-term courses are set, but short-term adjustments are always made. Singapore is small enough to behave like a speedboat—it can change course faster than a big oil tanker. Larger countries with sprawling bureaucracies often struggle with that.

“For centuries, architecture was local or regional. Materials, manpower, and resources all came from within a tight radius. Compare that to now, when we ship things halfway around the globe. The result is that cities look more and more alike.”

Let’s make a big swerve now into your work as an architectural curator and writer. So back in 2021, you curated ArchiFest, and you’ve also been editing Singapore Architect.

Ghilic-Micu: I’m just now passing the baton. I’ve been on the editorial team since 2017, and chief editor for the past four years, working closely with my friend Ronald Lim.

Oh, Ronald! I know him. I spoke to him years back about his social media account on Singapore Modernist buildings!

Ghilic-Micu: Yes, that’s the one. Ronald is an encyclopedia of Singapore’s history. He’s a close friend and a pleasure to work with.

So, with your experience editing Singapore Architect, you, Ronald, and the team have helped shape the trajectory of architectural discourse in Singapore and the region. How would you describe the current state of architecture journalism and critique in Southeast Asia? What’s the appetite? The constraints? And how would you compare it to Europe or the Americas, where criticism has centuries of scaffolding?

What sensibilities or skills do architects and allied creatives here need to cultivate in order to advance meaningful dialogue, especially in a region where critique is often still seen as taboo?

Ghilic-Micu: Very good question, and one I’ll answer cautiously. You’re right: there are real cultural differences in how architecture is consumed, reviewed, and critiqued. Part of it comes from lineage: Europe and the U.S. have had longer runways, centuries of discourse. But part of it is cultural.

In high-context cultures, where “face” matters, confrontation is approached differently. Critique isn’t meant to be a bashing of others’ work. In the West, critique can be confrontational, and that’s culturally appropriate there. Critics play a “church and state” role, keeping tabs on development. That’s tied to governance and procurement systems.

Here, when I wrote my first article, I was told: do it maturely. You can highlight challenges, celebrate strengths, and point to opportunities for improvement. That doesn’t mean bubble-wrapping opinions but being respectful and thoughtful. Critique shouldn’t devolve into “I like/I don’t like.” That’s not meaningful.

It’s also relative to the writer. Some architects are more comfortable than others with dialogue about their work. Personally, over the past 12 years in Singapore, as I read widely and write regularly, I’ve found architects here increasingly open to critique. They know they’re not infallible.

So architectural writing here has moved beyond glossy coffee-table spreads of pretty photos. Critique is starting to unpack ideas and drivers behind projects. That’s valuable. I read critique not as tabloid scandal, but as education.

When I read a piece of text about architecture, I want insight into the architect’s mind, as well as into the writer’s. I want to see how the writer balances what the architect claimed they were going to do with whether they actually delivered on it. That’s where healthy conversation lies. At the end of the day, you can only be judged by the targets you set for yourself.

So if someone says, “Oh, they designed a square building, but too bad, I like circles,” that’s a non-starter. That’s not a productive conversation. It has to be relative to the parameters the architect set and how those played out in the project.

For instance, if someone says, “We set out to do the most sustainable building in Singapore,” but first they demolished a tower to make way for it, the natural question is: what about all the carbon that went into the landfill? That’s the level of critique I think is healthy: it becomes a matter of principles, not personal attacks.

Exactly. We should be having those conversations because buildings aren’t mistakes you can just magic away! They are here to stay.

Ghilic-Micu: Right. They’re not Play-Doh. You can’t just reshape them. Or you can but at great cost. And this is why, speaking more broadly, the Philippines really needs a more robust culture of architectural critique. How else do you weigh the works of architects except by examining them against the values you want to promote when shaping your cities?

Take Bonifacio Global City, for example. As much as it represents a certain aspiration, I’d expect locals to warn me against holding it up as the image of Manila. It’s an outlier. Do we want to replicate that bubble everywhere? Of course not. You need seeds of good urban quality, yes, but the question is: how do you stitch them into the broader city fabric over time?

Leonor: I have a question, Razvan. You’re in design journalism, and I write as well. Doesn’t that put you in a position of authority, or responsibility, rather, to start these discourses? You put writing out into the world, people respond—but how do you move from writing to action? Are there platforms for that?

Ghilic-Micu: Events. Writing is powerful; when I contributed to Singapore Architect, Cubes, and INDESIGN, the reach was wide. But in parallel, I also organized debates and forums. That way, you can curate a lineup and offer alternative views to the status quo.

A turning point for me was when the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) allowed our team to curate an exhibition and two forums. One of them, Agents of Change, featured entrepreneurs like Karen Tan from The Projector, Kelley Cheng, Pan Yi Cheng, and Javier Perez. The conversation turned very real and raw—especially around barriers to innovation that are written into the building code and zoning. And this wasn’t in some fringe venue; it was held in the URA’s own theater, with URA staff in attendance.

The discussion wasn’t about throwing stones but about identifying how far innovation could go within the boundaries we had, and the challenges to future change. No, the code wasn’t rewritten the next day, but it mattered.

I always start from the premise that people are inherently good, with good intentions. But how can a developer or planner possibly know everything that’s out there? They have limited hours, families, and lives. So I see journalism and events as a way of surfacing ideas they might never encounter otherwise. Sometimes a single soundbite in a debate plants the seed for something bigger later.

That’s why I don’t only write; I also moderate, curate, and organize. Not to push my own agenda, but to be a kind of sherpa—to help speakers bring their ideas out and create the conditions for real exchange.

Leonor: Because that influence can even lead to policy reform, right?

Ghilic-Micu: Potentially. It’s a soft influence, but yes. And that’s why I call it a responsibility. Some architects get power-hungry, self-absorbed. But in the end, it’s not about serving yourself but about wielding your responsibility toward society, toward people, and planet. Putting ideas out there, trusting they’ll land somewhere, and maybe, over time, make a difference.

Leonor: Does that kind of critical culture really exist in Singapore?

Ghilic-Micu: It does. In the Philippines, from what I gather, people are less comfortable with critique. There’s a cultural fear of offending, of causing someone to “lose face.”

Leonor: What would you recommend for building that culture here?

Ghilic-Micu: I wouldn’t presume to prescribe anything specific; I don’t know the cultural context well enough. But in general, for societies that hold back from critique, one approach is to pilot small, carefully curated events. You inch outside the comfort zone, respectfully. Like therapy, you confront a fear in small doses. What happens if we ask harder questions? Does the world collapse? Or do we come out better?

Yes, it’s uncomfortable in the moment, but if the answer is “we can do better,” then it’s worth the discomfort. It’s more about evolution than revolution.

In the West, things often swing to extremes; big shocks, big reversals. In the East, where the collective identity is stronger, change tends to be slower, more cohesive, stretched across decades or even centuries. Both have their dynamics, but I find the Eastern mode ultimately more balanced.

You also teach at NUS, specifically involved in the architecture thesis programs. From your years in academia, what skills do you think young architects should develop to remain relevant and impactful? And with creative silos increasingly breaking down, where else do you see architecture making pivotal contributions to the human experience?

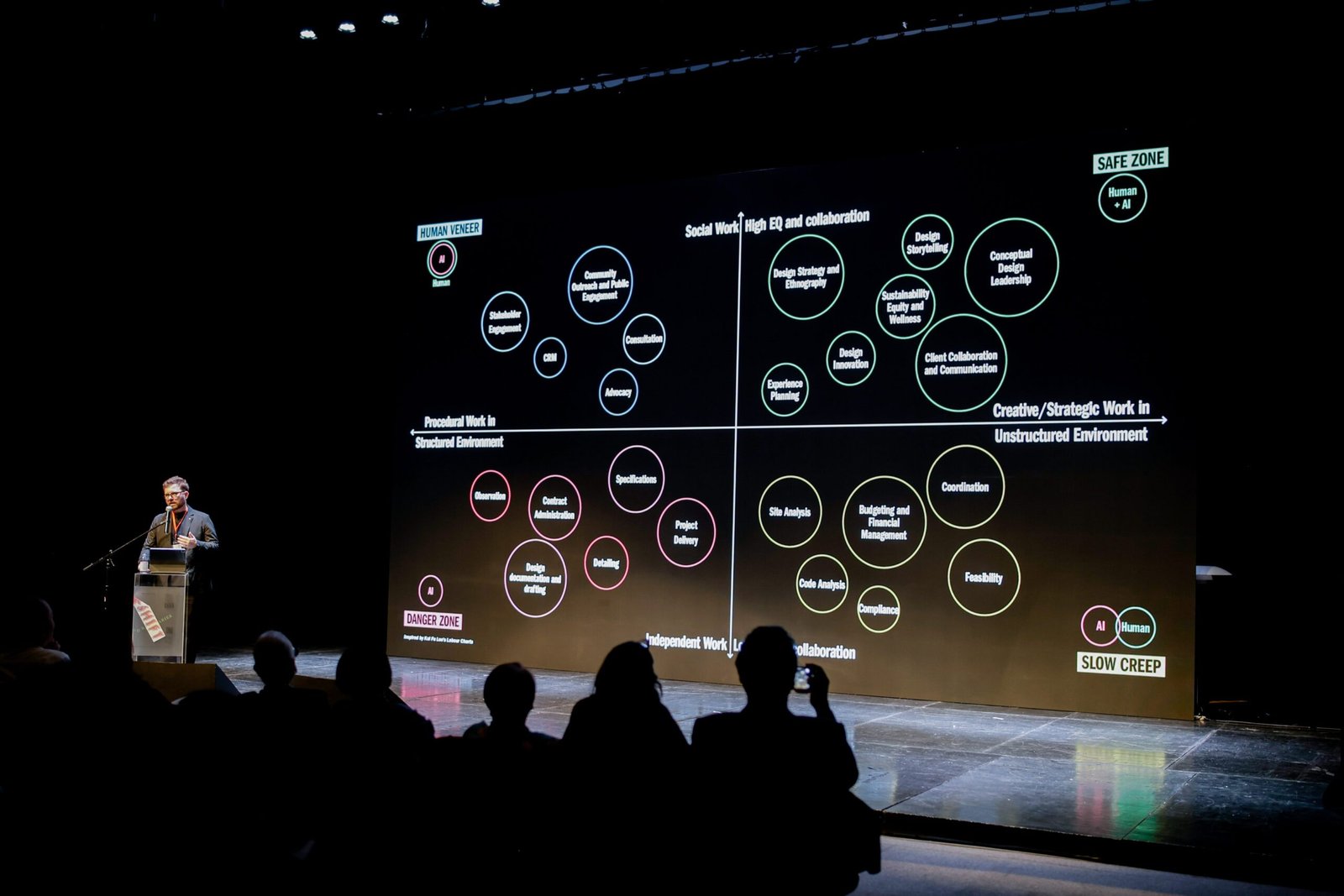

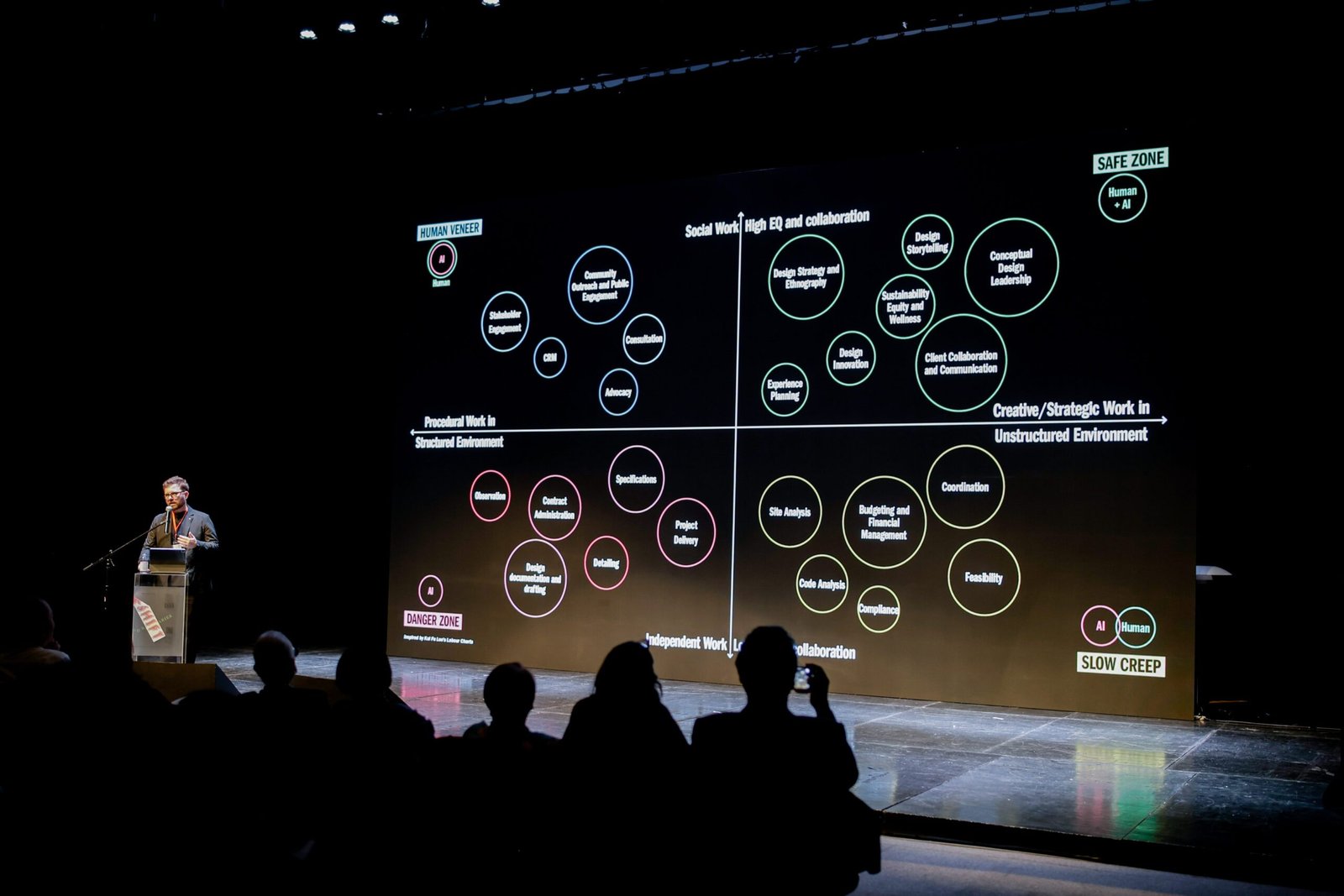

Ghilic-Micu: I had a chance to answer something similar recently in a URA publication. I think architecture has a broad bandwidth of what it can be, or what an architect can be, beyond just designing buildings. That’s been my position for years. ArchiFest in 2021 also explored this idea: how architects can contribute meaningfully to society in more than one way.

In school, this means fostering a deep appreciation for culture, the environment, and the fundamentals of architecture. If you choose to practice in the more conventional sense, like designing and constructing buildings, you’ll need to constantly challenge yourself in how you do it. Architecture shouldn’t be learned as a repetitive trade, like welding, where you repeat the same task to get the same result. You need to learn about yourself, your own way of thinking.

Today in my talk at MIDS, I hinted at something important: developing a healthy sense of self-awareness so you can challenge your own biases. That’s why we need to teach not just the history and theory of architecture—which is essential, because if you don’t know the past you risk repeating its mistakes—but also how to think. The only certainty about the future is uncertainty.

Even if we train students with hard skills and codes, by the time they graduate, much of that will already be obsolete. Things change too quickly. So the point is to teach them how to think and to give them opportunities to test themselves in a variety of challenges. Because it’s only by testing yourself that you understand your limits, your processes, and your biases. Then, when you face real-life challenges, especially when money is involved, you won’t freeze. You’ll find a way through.

And that’s why I think the idea of “one right way of doing architecture,” which is still taught in some schools, is so misguided. Instead, education should give young architects the chance to test themselves against a spectrum of challenges. That way, when the unexpected comes—and it always does—they’ll already know how they operate. They’ll face it with an open mind and a clarity of mission. •