Interview Patrick Kasingsing

Images Modernist Architecture Singapore

Hello! Hope you’re faring well there in Singapore. Do introduce yourself!

My name’s Ronald Lim. I’m an architect in an independent practice in Singapore. I am also an editor for The Singapore Architect (the Singapore Institute of Architects’ official magazine) and teach design at the National University of Singapore. I guess these extra-curriculars reflect my interest in architecture as a cultural and intellectual practice beyond being a professional who needs to make a living.

Your firm, Ronald Lim Architect, manages this wonderful Instagram account called @modernistarchitecturesingapore. As its name suggests, the account shares imagery and intel on the modernist architecture movement in Singapore. What led the firm to start the account?

It’s a long-winded story that spans over a decade.

I have always been interested in the Modern Movement in architecture. As an undergraduate, I had inspiring professors who opened my eyes to this world and how it came to be. The chance to visit such canonical buildings as Le Corbusier’s La Tourette and Unite d’Habitation and Pierre Charreau’s Maison de Verre—among many others—inspired me to pursue architecture further.

During my graduate school at Yale (2008 – 2011), my dean convened a series of retrospective exhibitions that interrogated the legacy of important Late-Modern, Yale-affiliated architects like Paul Rudolph, Eero Saarinen, and Robert Venturi. I had also earlier worked in the office of Cesar Pelli, who used to be Saarinen’s project architect, so the design genealogy felt personal. Inhabiting a masterpiece by Paul Rudolph (i.e. his Art & Architecture Building) and being next to two important buildings by Louis Kahn were their own living inspiration. Think of it as being a fish swimming in the waters of Late Modernism. It was just ever-present, and I was very enamored by it. To top these off, I went to work briefly for Fumihiko Maki, the Japanese Metabolist architect, after graduation.

Interestingly, Yale was the perfect setting to research Singapore’s architecture from this period (1960s – 1970s). Its library system had amazing Singapore-related primary source materials. Understanding the international modern canon helped me recognize the sophistication of many local buildings – especially the ones by the Malayan Architects Co-Partnership. Like the Yale exhibitions, I imagined that a MoMA-quality retrospective exhibition or monograph could burnish the legacy of these heroes like Lim Chong Keat. But I also felt that someone else, perhaps an architectural historian, would be better qualified to tell this story while I hunkered down to become an architect.

I guess it took me time to realize that I was qualified to tell this story with an original perspective. I hadn’t realized how accessible Instagram was. It really lowered the barriers to curatorship compared to organizing an exhibition or researching to write a book.

What would you say is your end goal for the account?

I don’t think I have an explicit goal. It’s more of an attempt to shape a conversation.

Another reason I started this account was that, in Singapore’s saturated market, creative opportunities for young architects are scarce. One hope is that it may open up opportunities for me with, say, a “white knight” client who owns an aging Modernist building and would value my involvement. An adaptive reuse project would be a dream commission since it involves revealing historical layers with a meaningful contemporary intervention.

More broadly, this account is a platform to raise awareness and help others see these Modernist buildings differently since they are sometimes misunderstood. We may have restored post-war monuments like Jurong Town Hall and created cult followings for icons like the Golden Mile Complex, but these are just the tip of the iceberg. We remain oblivious to the legacy of many accomplished architects. This is partly because deeper research, documentation, and dissemination are needed. I, therefore, see this account as an informal database and curatorial scrapbook. The information may be incomplete or even erroneous but at least it fills in some documentation vacuum and creates awareness.

We are, by and large an amnesic society. It’s easy to take for granted beautiful buildings once they recede into the every day and their design vision is not readily apparent. Society’s ignorance or indifference to a building’s cultural value can abet its unthinking removal. If I could offer a historical reminder, our many beautiful, ornate shophouses were once unsightly slums. They were severely neglected before their conservation allowed people to perceive them differently. For our generation, the fight is for these Modernist buildings. If the public learns to value them, then decision-makers (whether developers or bureaucrats) do not have carte blanche and will be obliged to work out solutions with stakeholders.

Going forward, it’s the more recent Post-Modern, Deconstructivist, and Neo-Modern buildings (roughly 15 to 30 years old) that I’m equally worried about. They are not old and quaint enough to be deemed heritage and can seem unfashionably dated to the uninformed, even if they are highly accomplished. We have even lost seminal buildings built as recently as 2001(!). Whether young or old, the best-designed buildings are a veritable part of our culture. They should be allowed to last. It’s painful to see beautiful architecture demolished and replaced with something unmemorable or ugly. This has happened too many times.

Are there plans to transcend Instagram and embark on more forms of interaction? There seems to be a growing interest in the content that you are disseminating.

I do have links with the architectural profession, academia, and heritage champions in the government. We mostly know each other. The challenge is that it is insufficient for professionals alone to grapple with these issues without public support and discourse. Collective progress happens only when there is momentum and support across the breadth of society, government, and the private sector.

So, I think the process is reversed. It is about exploring Instagram’s potential as a 21st-century media platform to open new conversations, generate public interest, and shift the discourse. It may take some effort to blend Instagram’s “visual candy” appeal with a more serious intent—a bit like sugar-coated spinach. This could create momentum to influence key players’ decision-making. It would also delight me if owners of existing Modernist buildings start to appreciate their own properties differently after following the account.

Modernism as a style had its own set of rules and characteristics, but we’ve seen how countries where it landed have given this international movement an injection of local flavor. What makes Singaporean modernism different?

I doubt a definitive answer exists. As a neutral observer, I’ve reflected on what makes Modernism different in settings like Japan, Mexico, or even the US – hoping to unlock some magic insight into Singapore. There isn’t one. I would say that when architecture is created in a place and culture, it has to remediate local factors like climate, local construction technology, living habits, and available materials. If there were sincerity and awareness during the design process, the result is naturally contextual. This arises more from an organic process than specific or prescriptive precepts.

Of course, the architects’ cultural self-awareness bears an influence. In the 1960s, although many architects in Singapore were of Chinese origin, their vernacular references were actually Malay. Seow Eu Jin, the eventual head of the University of Singapore’s Department of Architecture, published an essay called “The Malayan Touch” exploring the adaptive, tectonic potential of traditional Malay houses. This slightly predated Singapore’s independence when our national project was to construct a Malayan or Malaysian identity. Some architecture from this period reflects this Malayan awareness – like Lim Chong Keat’s Singapore Conference Hall or Alfred Wong’s National Theatre.

Having said that, I am often more astounded by how these buildings reflect prevailing currents in global architectural thinking. I think the overarching project (whether in Singapore, India, or Latin America) was the same, i.e. to construct a modern, emancipated society for a post-colonial nation. Architecture was a tool for nation-building.

There is always that debate between development and preservation, enhanced still in a land-scarce country like Singapore. Are there options out there to get the best of both?

This is an extremely complex question. As someone who has served clients, managed dollars and cents and dealt with government departments, I understand the thinking and limitations that each side faces.

I would say “yes” if we had a robust, inclusive, and transparent process that lays upfront all the competing issues, interests, and trade-offs. For example, if a developer acquires a heritage property, he may not be able to maximize his rentable area by fully conserving the original structure. He may need to demolish one wing to build an efficiently configured, revenue-generating addition. Should he be allowed to do so? If not, would he even buy the property and rejuvenate it? If we gazette a building for conservation, does it unfairly penalize its owners by curtailing its redevelopment potential? An inclusive and robust due process can remediate these difficult issues, assuming we share common goals and principles. The final outcome may need everyone to compromise.

In Singapore, the government tends to deliberate on key decisions privately and seek public feedback only after the direction is set. This is their general modus operandi, with some exceptions. When this happens, stakeholder input has limited effect on the outcome because this happens too far downstream. It’s important for all stakeholder concerns to be captured upstream, i.e. at the start of the process when solutions are being ideated on. I do understand this prevailing habit because the more constituents one engages, the less autonomy there is to do things decisively.

Interestingly and ironically, the fate of redevelopment that befalls our built heritage stems from policies that are intended to benefit us in the long term. Most condominiums are on an expiring 99-year lease. Once the lease expires, it reverts to government ownership. The underlying premise is that the future government can use this land for future needs. It is ultimately a good policy. Unfortunately, this same expiring lease makes condominium owners anxious to cash out once their properties are 30 or 40 years old. Also, the government only approves lease renewal if the land use is intensified. The general dynamic privileges redevelopment.

To cut a long story short, the issues and trade-offs are complex. The big challenge is for heritage to find a business model to withstand these economic pressures. The government is currently exploring tax incentives to entice developers to preserve Golden Mile Complex. Some intervention is definitely needed to give the heritage a leg up.

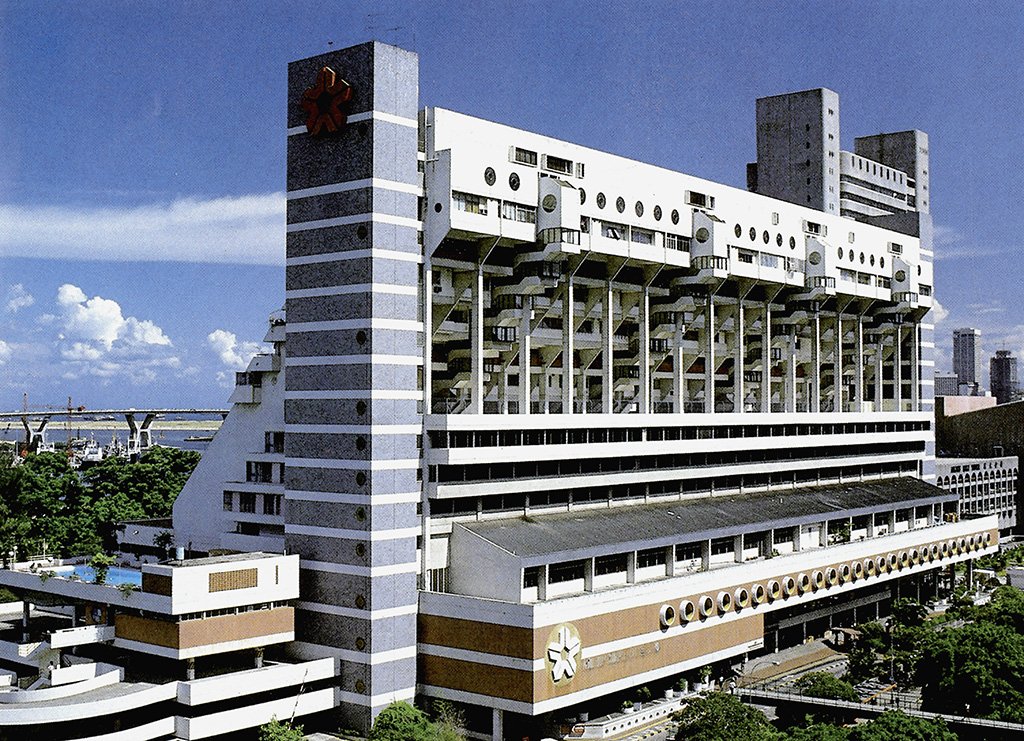

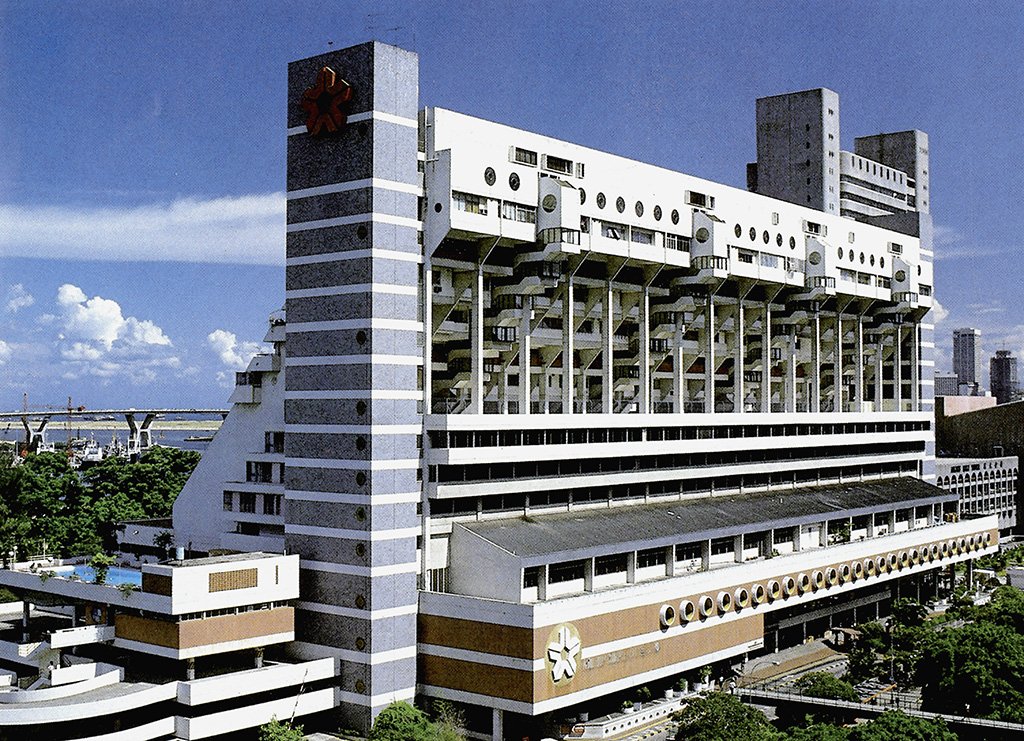

Anson Centre (completed 1971, by Yao & Quek Architects). Photography by Shunann Chen

Telecoms City South Exchange (completed 1970s, by Group 2 Architects). Photography by Shunann Chen

How do you curate or decide which buildings to post about? Where do you often source out your images and building intel?

I’m extremely lucky in that regard. I can find good material partly because the Singapore National Archives has digitized part of its collection. Historical annual reports of government departments, photos, and historical newspaper articles are retrievable from my desktop at home, so it’s possible to source good images of government-commissioned architecture. Our National Reference Library is also an excellent resource, and I sometimes make physical visits. Every visit is a visual feast. I consult my own library when I need to verify a building reference (e.g., a building by I.M. Pei or James Stirling, etc) to confirm its relevance.

There’s no hard and fast rule as to which building gets posted. It usually happens when enough good images of the building can be found. I have to straddle multiple sources or publications. It’s actually gratifying when these different sources tally. A good friend and ex-colleague of mine, Shunann, is also a Modernist geek himself and loves photo-documenting these old buildings as a pastime. We often bounce ideas and Google Street View finds off each other. In the language of tech businesses, he would be my “content partner,” so to speak.

Also, it is a balancing act between posting all-time favorites versus lesser-known buildings. I usually amplify the coverage of the latter. That said, there is a “visual candy” aspect to Instagram, and it’s a bit of a beauty contest to garner likes, so I have to plan big, impactful posts every so often. It’s not easy to keep up the momentum. Sometimes, when I go too deep into the research, I grow a bit scatterbrained and find myself at a loss over what to post.

How has your learnings and research informed the way you run your firm? How is the initiative reflective of your studio’s design philosophy?

I don’t think it informs how my own practice runs, but it definitely seeps into my own design consciousness. Architects today are under great pressure to create designs that look chic and trendy in a globalized, photogenic way—whether through sleek lighting or contemporary finishes. I find that a lot of local ’60s Modernist designs have richer local cultural inflections through the use of sensual materials like local timber or design patterns informed by craft (e.g., a batik-inspired mosaic wall pattern) or bold abstract shapes that feel culturally familiar.

I doubt those architects were particularly conscious of being Southeast Asian, but they drew on local culture to create stylish designs that were comfortable in their own skin. They were local and cosmopolitan at the same time. I find it authentic and inspiring. Of course, our context is different today. Natural timber used to be affordable, now it’s expensive. Brick was once an everyday material but is being displaced by pre-fabrication today. I do think we should re-examine aspects of vernacular craft and culture—not as a contrived nostalgic fetish—but to understand what we unknowingly discarded as we became a developed global city.

Are there recent examples of adaptive reuse/conservation of heritage architecture in Singapore that you think can serve as a good template for other developments?

The restoration of post-independence state buildings like Jurong Town Hall and the Subordinate Courts has been quite well done. These landmarks have found a new lease of life. However, because the state owns these buildings, it is not a good model for other privately owned buildings in danger of demolition.

Among commercial properties, I think the repurposing of the Asia Insurance Building, a 20-story Art Deco building in Raffles Place, into serviced apartments offers one viable model. There are really no straightforward commercial templates. Some of the examples we see in the UK (e.g. the remodeling of Park Hill Estate into upscale apartments) are difficult to apply here because the property cost alone affects the math. On a per-square-foot basis, spacious apartments designed in the 1970s or 1980s are beyond today’s range of affordability.

The most challenging part is to work out an economic formula that gives the building a new lease of life but preserves its integrity. Currently, the operative model is for the government to acquire such heritage buildings, like Capitol Theater, and tender this building with an adjacent plot of land to the most attractive bid with conditions attached. The heritage building is then integrated into a larger commercial developed or as a boutique hotel annex. The heritage building may end up as a bland simulacrum of the original. It’s better than losing the building, but it’s not necessarily the best outcome for the city. Some authenticity is lost in the process.

In terms of “bottom-up” stakeholder and community engagement that allows the building’s original life to continue, I like the example set by the rejuvenation of Chowrasta Market in Penang, Malaysia (by Arkitek LLA). We’ll probably have to take a couple of blind stabs to figure out a private sector model that better preserves heritage integrity.

We’ve seen how en bloc sales could threaten the existence of iconic heritage landmarks like Pearlbank, for example. What are some ways the government or private sector can inspire awareness and appreciation of what remains of Singapore’s modernist heritage?

Nothing beats public example. If good buildings are painstakingly restored to their original design vision and the public can access them, they will treasure them as cultural assets. A few state buildings are taking this route.

Also, we can better celebrate the role of architecture in national myth, however contrived or nationalistic that sounds. Since independence, we have depicted colonial buildings like the Supreme Court, City Hall, or the Istana Presidential Palace as emblems of statehood. We can include post-independence architecture in this narrative and illustrate their role in history (e.g. the Singapore Conference Hall and Singapore’s trade union movement). Often, modernist buildings resonate with ordinary folk because of their personal memories, even if they do not fully understand the building’s design vision. There is definitely room to weave architecture into more compelling narratives.

I think that the private sector, in its self-interest, would want to harness the marketing value of good architecture—especially where it grows its brand. Over the last decades, we have seen the blend of design culture with lifestyle consumerism, best exemplified by Aesop boutiques or that ubiquitous Monocle-chic look. Lifestyle consumers seek imageable experiences that embody sophistication. I see Modernist heritage fitting snugly into this strand of consumerism. As always, the challenge in Singapore is that rent and property cost severely distorts the financial calculus for retail risk-taking.

Still related to public awareness, would you say that the present Singapore architecture curriculum adequately covers the Singapore post-war, modernist experience? What can be improved?

Our architecture students are definitely taught local and Southeast Asian architectural history, including post-independence buildings. I have not reviewed the syllabus to comment fairly, but their professors are definitely passionate about what they teach. Having said that, architecture school is intense and architecture students have a lot on their plate. I teach some of them and sometimes understand why they sometimes “switch off” from what is being taught. Ultimately, passion arises where there is personal meaning, so I hope the young ones make their own discovery on a cause they care about.

If you could pick three architects or firms and three modernist buildings in Singapore that can best provide a briefer on the modernist movement for the uninitiated, which would it be?

This is a difficult question. It’s like asking a parent to pick favorites.

I would start with the Malayan Architects Co-Partnership (MAC) – founded in 1960 by Lim Chong Keat, William Lim, and Chen Voon Fee. This firm dissolved in 1967 to Design Partnership (DP), led by William Lim, and Architects Team 3 (AT3), led by Lim Chong Keat. These successor firms had further offshoots in Kuala Lumpur. If these 3 firms were one collective entity, I would pick the three following landmarks:

1. The Singapore Conference Hall (1965 – MAC)

2. Jurong Town Hall (1974 – by AT3)

3. Golden Mile Complex (1975 – by DP)

For a second entity, I would pick Alfred Wong Partnership. He designed a great many landmarks but his first among equals was the National Theatre (1963, demolished 1984).

For a third entity, I would actually pick the government. Many nondescript modernist buildings that left considerable social impact were designed by government architects. If I had to single out one project, I would pick the Outram Housing Estate (1969, demolished early 2000s). It was supposedly designed by Alan Choe, Singapore’s first Chief Planner.

As this is our heirloom issue, why is looking back at the past just as vital as having a future-forward mindset?

The past, the present, and the future are all important parts of ourselves. The more we can coherently reconcile who we were, who we are, and who we will be, the more we feel secure about being in our own skin. If we know where we come from, we will have the confidence to stay authentic when confronting a world of unknowns. •

CPF Tower (completed 1974, by Architects Department, Public Works Department, Singapore) Demolished, 2019. Source: CPF Annual Report 1977

Haw Par Glass Tower (completed 1974 by K. K. Tan & Associates). Source: URA Annual Report 1974

Interested persons may send queries to info@rla.sg