Introduction and interview Patrick Kasingsing

Images Bien Alvarez, Moritz Bernoully, with Patrick Kasingsing (Sulog)

Editor’s note*

*Sulog co-curator Patrick Kasingsing is also the editor-in-chief and founder of Kanto.PH

One can say that the roiling currents that brought forth Sulog, Cebuano for water currents, simmered from a place of quiet frustration. Years ago, a well-known Western author outrightly dismissed Filipino architecture as indistinct and unworthy of inclusion in his coffee-table book on tropical architecture in Southeast Asia. Being privy to that exclusion made me genuinely question: what is it about our spaces, and I’ve seen my share of striking architectural work across the Philippines as creative director of an architecture magazine, that renders them invisible or generic through foreign lenses?

After that tome came a book I wanted to exist: DOM Publishers’ Architecture Guide Manila, written by Bianca Weeko Martin, a young, precocious Filipino-Indonesian researcher whose bones, as she said, cried out for a homeland she barely knew. I gave her everything I could: contacts, photography, and research my team and I had gathered through Brutalist Pilipinas, our heritage advocacy group. After the pandemic pause, the book finally launched in 2024 at the Metropolitan Theater, and there I met Filipino-German museum director Peter Cachola Schmal. Unbeknownst to me, he was seeking a curator for a show on Philippine architecture, in conjunction with the country’s designation as Guest of Honor at the Frankfurter Buchmesse. A few weeks, a city tour, and some conversations later, I became the unlikely curator he was searching for. I remain grateful to Peter for his trust.

My inexperience as a first-time exhibit curator quickly surfaced. While Peter and I had clear fields we wanted to explore, Filipino diaspora, tropicality, and climate change, we needed a strong framework. I didn’t want to simply present a collection of beautiful spaces and risk becoming complicit in the same genericism that had once dismissed our architectural vernacular.

Thanks to my commissioning body, the National Commission for Culture and the Arts, I was joined by someone they had long trusted: my co-curator Edson Cabalfin. His breadth of architectural knowledge brought the force and clarity the show needed. With his inclusion of Arjun Appadurai’s Global Cultural Flow theory, my initial list expanded, and our curatorial process became more stringent, more evocative, more representative of the country’s multitudinous nature. From a shortlist of ten came thirty spaces and places, with each major island group and gender represented, bridging emerging talent and established names.

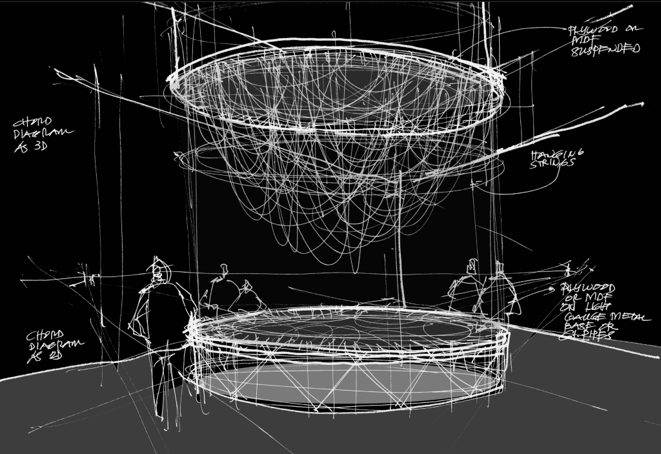

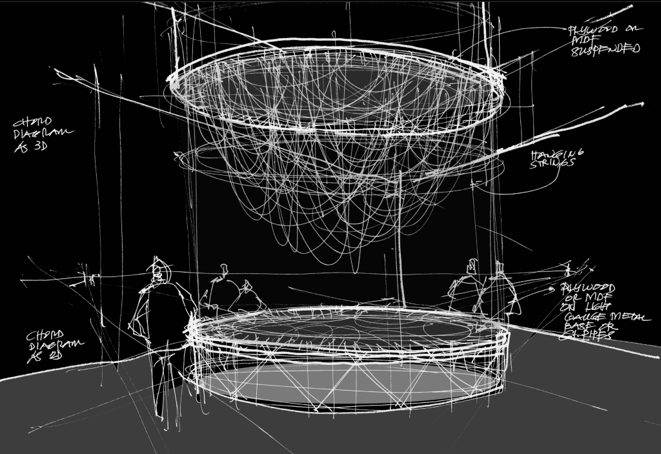

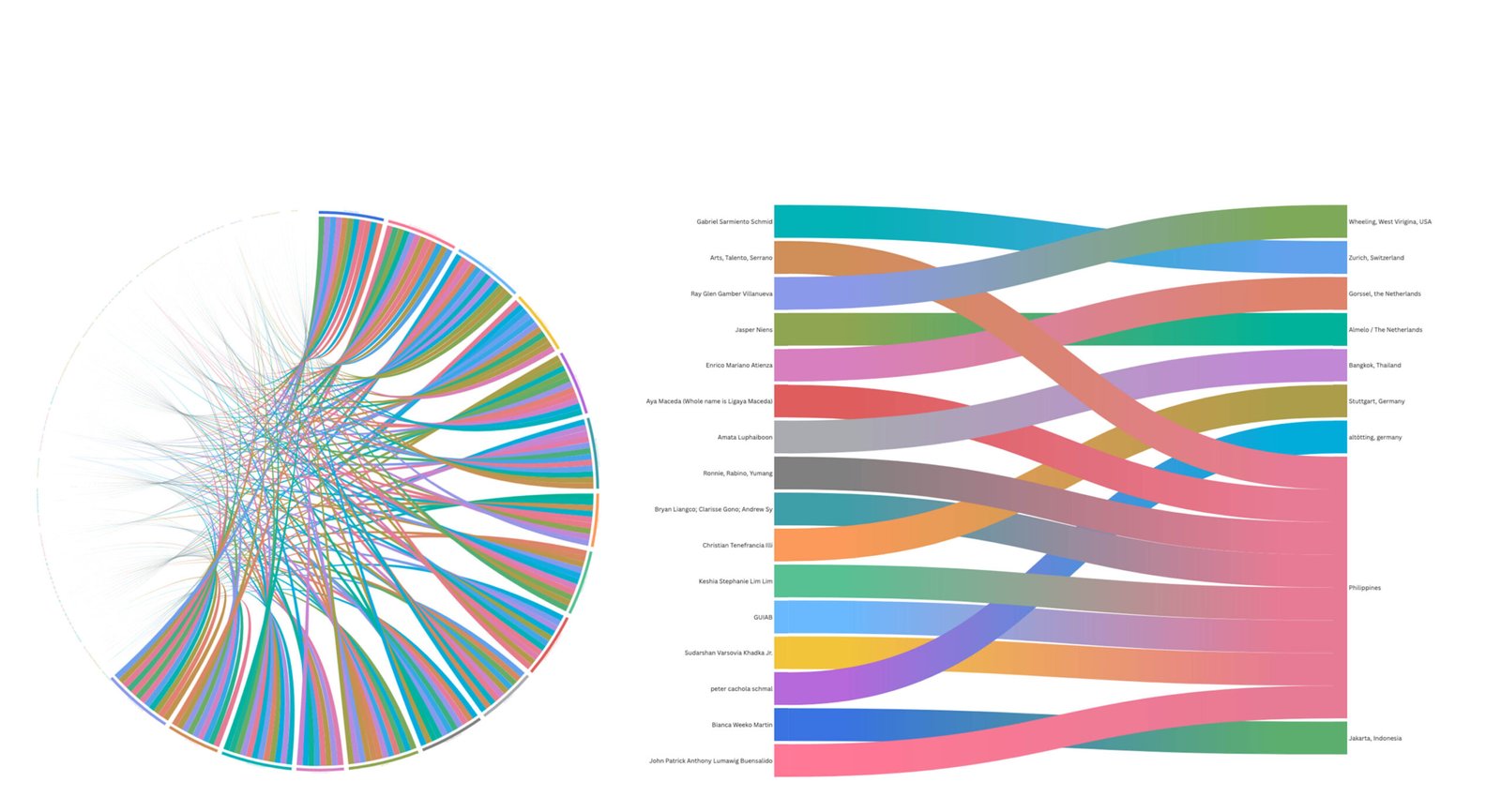

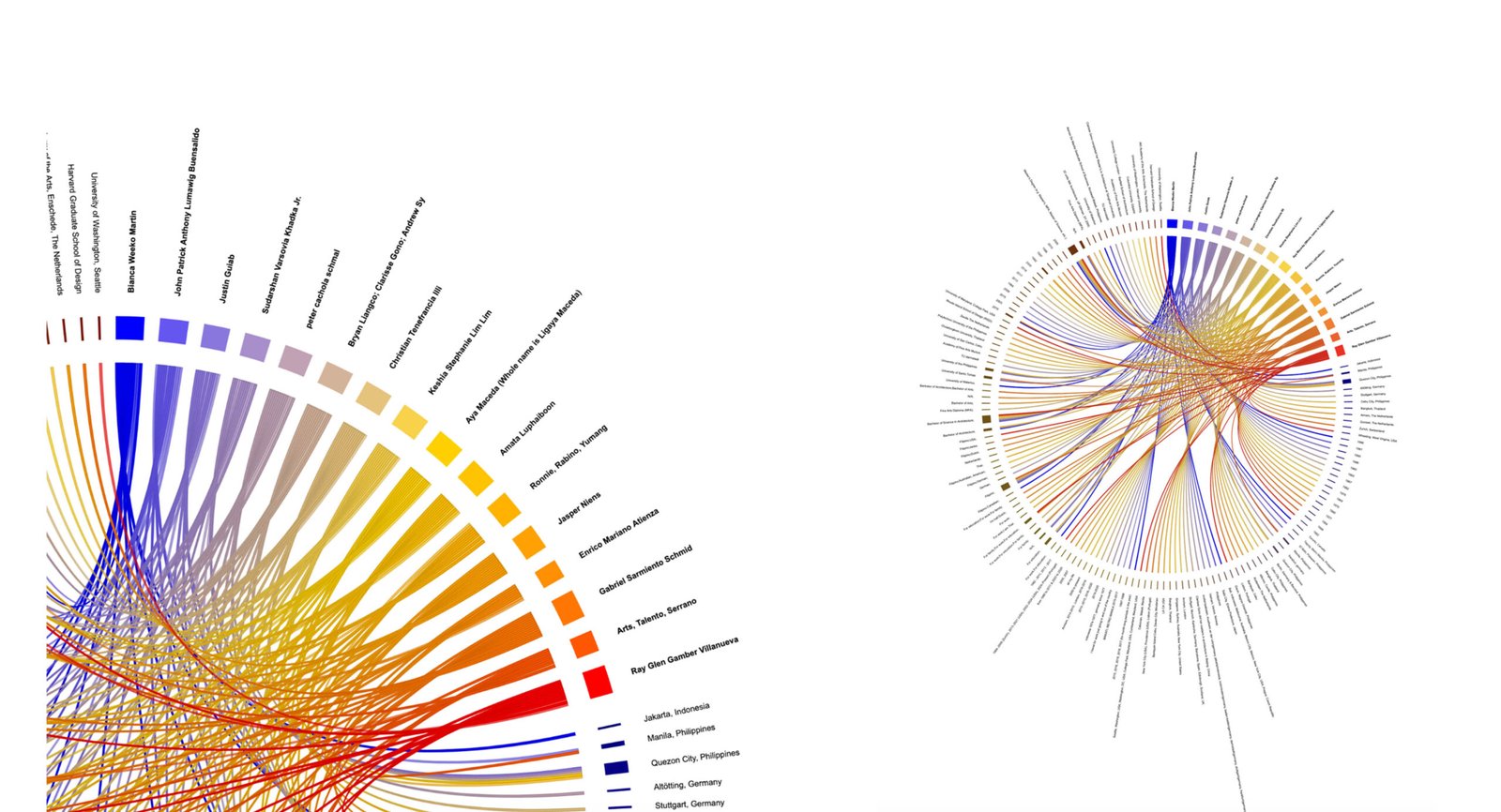

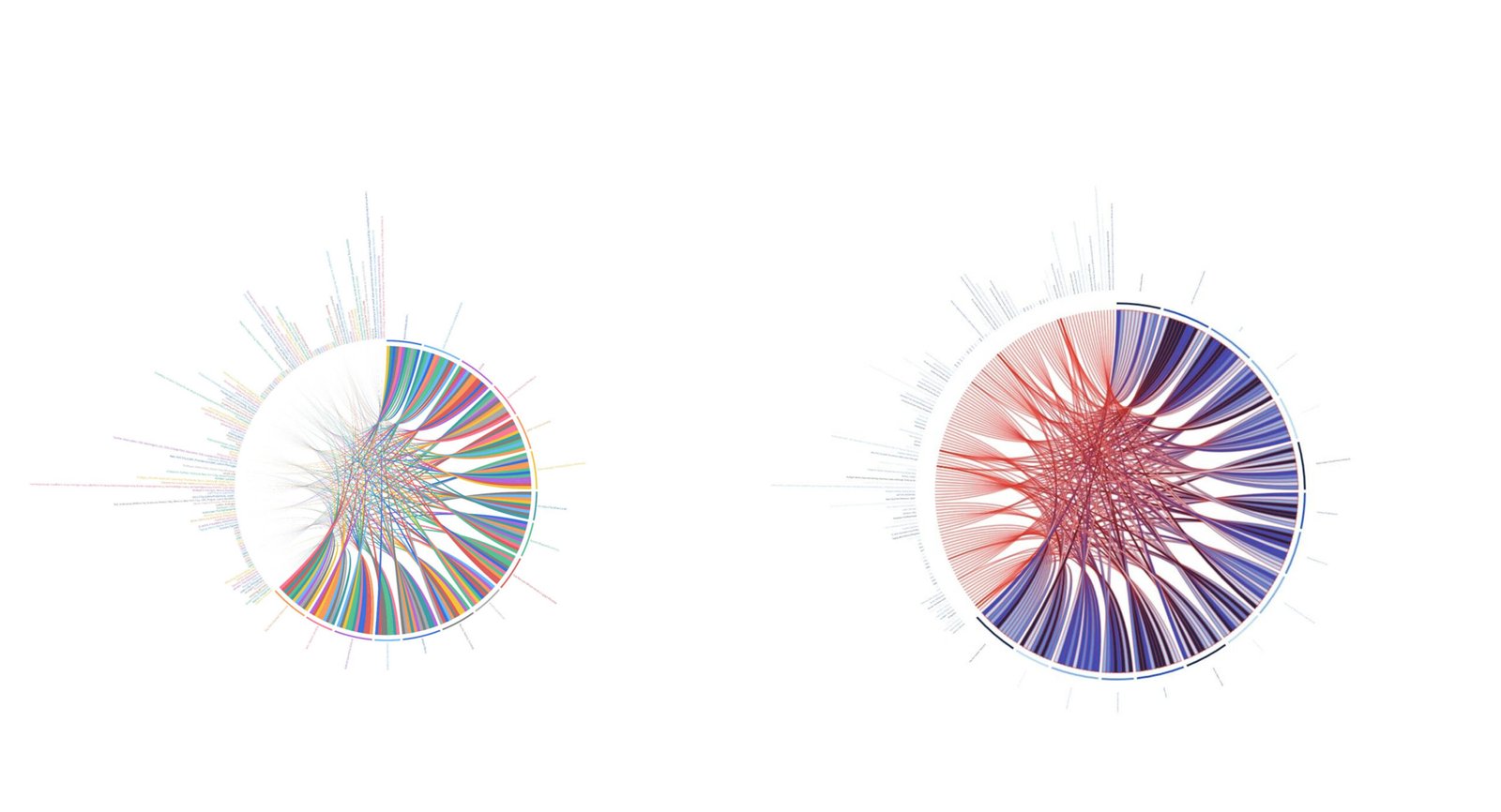

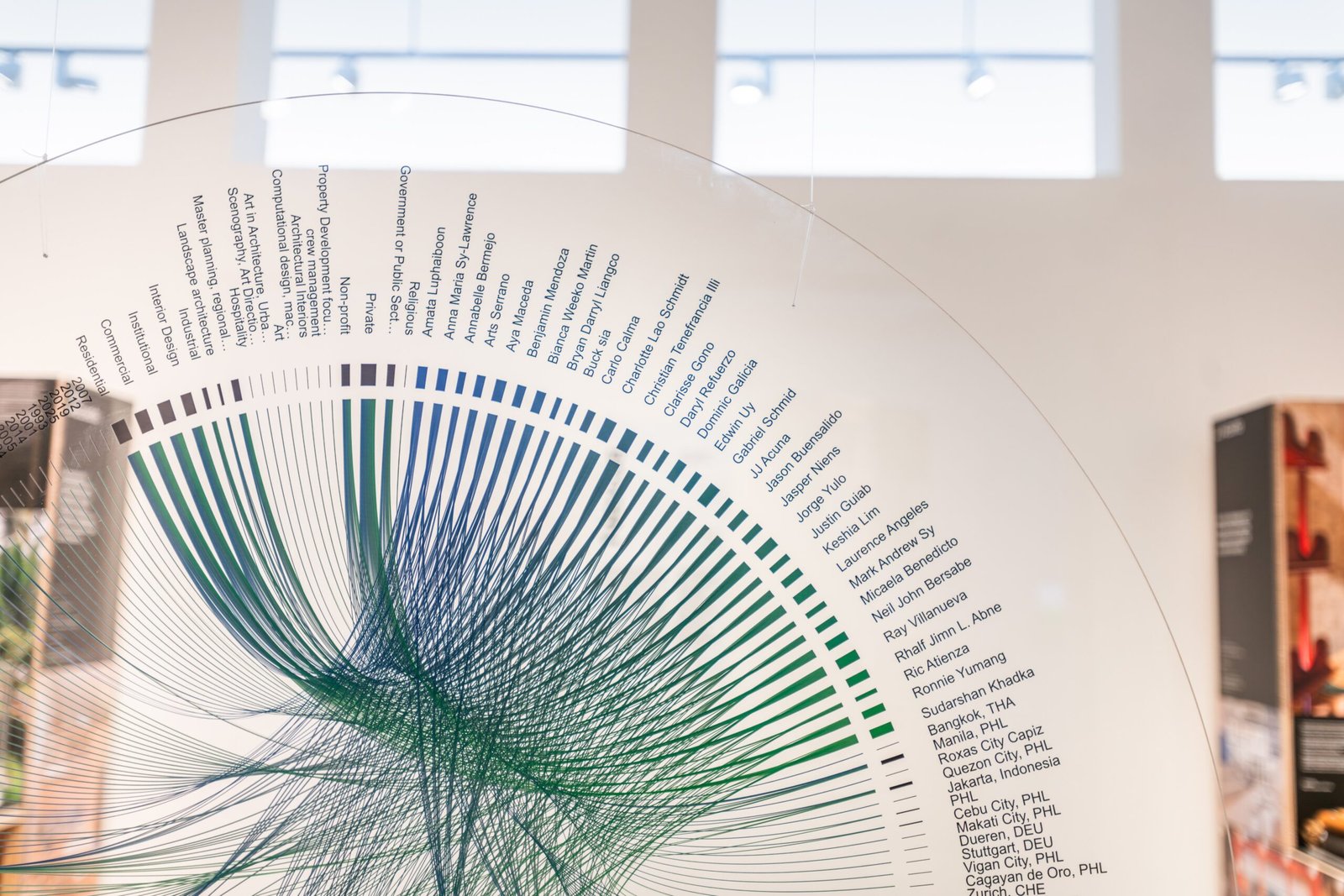

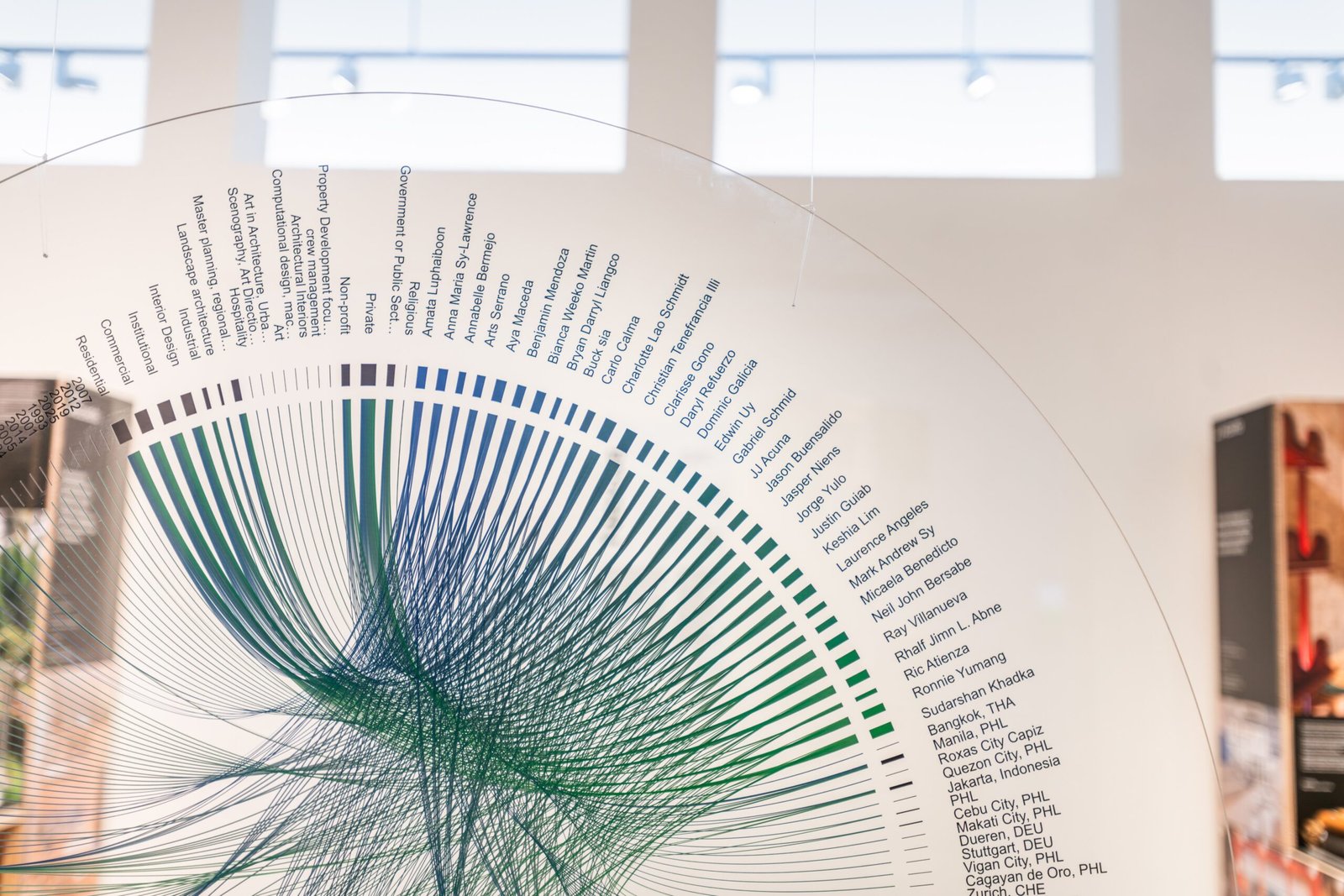

What could have been a steady procession of works instead ebbed and flowed with the energy of the country, in all its grain and texture. It drew from young passion and the wisdom of the ages, and embraced a more experimental, less siloed conversation with our bountiful shores. This was best encapsulated in an installation (the handiwork of Venice Biennale wunderkinds Bien Alvarez and Lyle La Madrid): an acrylic disc suspended within DAM’s house-shaped volume, almost like a minimalist bahay kubo. Etched on the disc was a chord diagram connecting names, places, and points of relation—an intricate network of empathy, cultural exchange, and creation that a mere parade of works could never achieve.

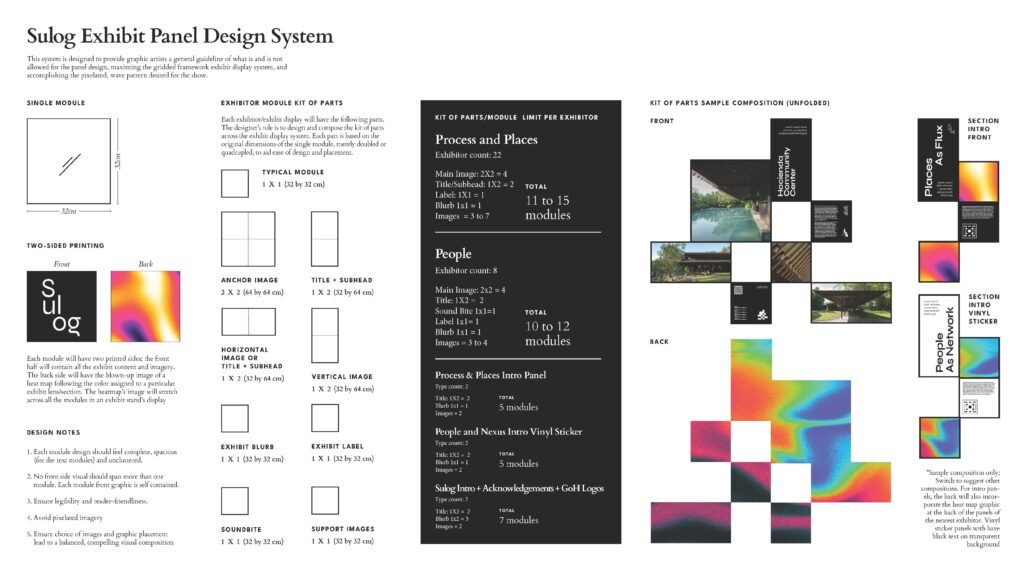

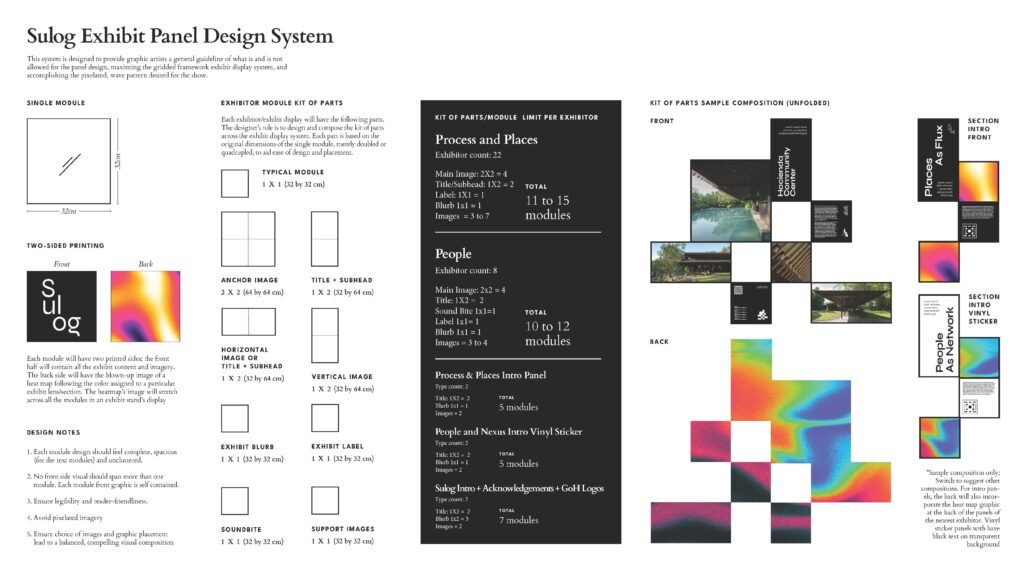

With our stellar cast of architects and spacemakers, Edson’s exhibition display system of pixelated grids, my art direction drawing from heat maps and water currents, and the indefatigable work of our writers and designers, Sulog was free to run its course and pour its message into German and international audiences, a snapshot of an architectural narrative that is ever evolving.

In hindsight, Sulog was never meant to exist in the timescale of that Western author and his book. It had to happen now, when Filipino architects are more confident, more attuned to context, more willing to explore complexity. The exhibition arrives in a moment of heightened urgency: a time of widespread fear and discrimination, when the world is freer than ever to speak its truths, yet quicker to silence voices that challenge control.

It has been two months since Sulog launched, and I welcomed the chance to reconnect with my co-curator Edson Cabalfin for a reflection on the show. Our conversation revisits how the exhibition came together: from its framing and flow to the questions we kept returning to as we shaped this evolving portrait of Filipino architecture.

Hello Edson! I sure missed our regular meetings, nearly a year of them discussing the show! I’m glad we are doing this for the benefit of Filipino readers this time.

When audiences first step into Sulog, they encounter Filipino architecture at the “crosscurrents” rather than as fixed or inert spaces. What do you hope this framing unlocks for someone who might only have a vague idea of what Filipino architecture is?

As an exhibit about Filipino architecture displayed at the Deutsches Architekturmuseum (DAM) in Frankfurt, Germany, I am aware of what German visitors might know — or not—about the Philippines and Filipino architecture. Exhibition visitors, for example, might not be familiar with the tropical context or with the architectural culture of the Philippines. The exhibition must, to a certain extent, introduce the Philippines as an archipelagic nation and, at the same time, explain current issues in architecture.

Additionally, I think there is a general perception of the Philippines as less progressive or trapped in the past compared to its Southeast Asian neighbors, and I wanted to change this notion. I was also aware that architecture is often thought of as limited only to buildings and, therefore, treated as an inert, passive object. The exhibition argues that Filipino architecture is part of a dynamic network and flows of people, places, and processes. I hope that visitors experience the exhibit and be exposed to the plurality of examples, then they will understand Filipino architecture not just as one singular thing, but as a complex, diverse, and ever-changing phenomenon.

We resisted treating architecture as a collection of isolated objects from the very beginning. How do you think our decision to foreground relationships: between people, places, and practices, changed the way visitors move through and engage with the exhibition?

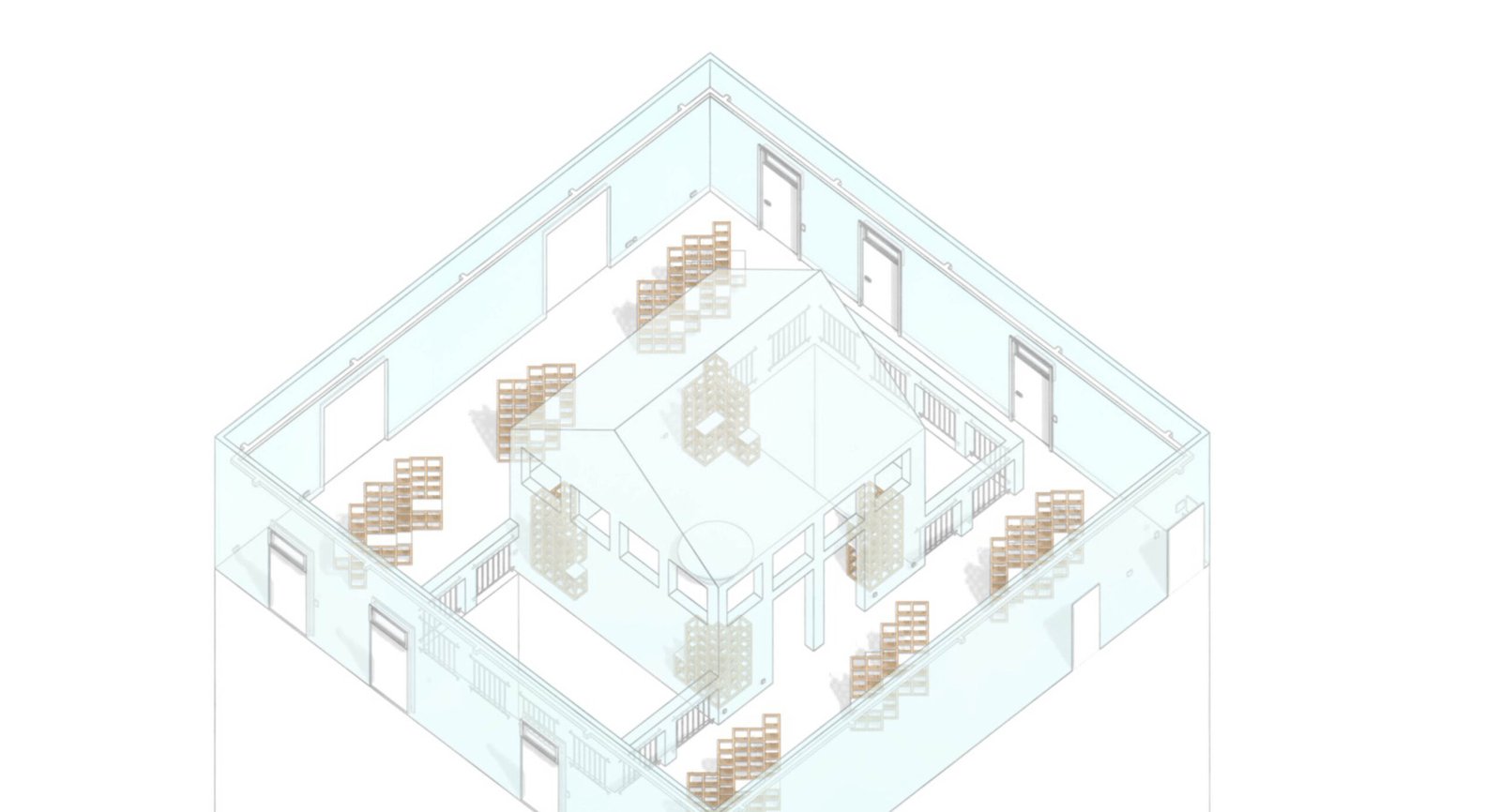

The primary message of the exhibit is truly grounded in the idea of relationships, whether they be through people, places, or practices. For the first section, “People as Network”, we highlighted eight transnational practices of Filipino architects and designers who are products of architectural education from across the world and/or are engaged in practices within and outside the Philippines. Through diaspora, Filipino architects and designers move and practice across countries, exemplifying the dynamic movement of people across different social, economic, and political milieus. The second section, “Places as Flux”, showcased fifteen examples of architecture sensitively responding to the myriad site factors that exist in a place. This section also underscores the need for architects and designers to have a symbiotic relationship with place. In the third section, “Process of Flows”, seven methods for making architecture are featured to emphasize the creative process Filipinos use to address challenges.

By highlighting the relational and intersecting connections between different examples and issues in architecture, we might be able to see Filipino architecture in a different light beyond the static conception of architectural practice. The thirty examples we featured in the exhibit are exceptional as individual case studies, but when brought together as a collection, we can see that Filipino architecture’s strength emerges from its connections across people, places, and processes.

In terms of moving through the exhibition, the three sections were not arranged in a linear sequence, allowing visitors to wander and make their own connections. This non-linear presentation also emphasizes the relational quality of the examples: the associations might not be a one-to-one correspondence or a direct line between the case studies, but could be a circuitous, indirect, and meandering relationship. This also means there is no right or wrong understanding of the relationships, but they could emerge from a series of pathways or routes.

As we were building Sulog, we were constantly negotiating between scholarship, exhibition design, and institutional demands. Looking back, which part of that tension most shifted the way you think about the role of a curator?

Having curated exhibitions before, such as the Philippine Pavilion at the 16th Venice Architecture Biennale in 2018, I was aware of the complexities in conceptualizing and implementing exhibitions in an international context. I was also sensitive to the fact that every exhibition and museum is different, with its own particularities and idiosyncrasies. With these in mind, I always prepare to adapt to the ever-changing situations that can arise during the development and installation of an exhibition. One cannot expect everything to go as planned or as imagined. One should be ready to pivot and make quick decisions as certain situations arise.

For Sulog, this meant addressing challenges head-on and not shying away from the issues at hand, including production, logistics, and even philosophical and theoretical questions. I also think that, as curators, while we might think that we have power or authority, we need to act as conscientious conduits of ideas and institutions.

Much like the exhibit’s core idea of “sulog,” a concept stemming from the Cebuano word for “water currents” or “streams,” one must embrace the dynamic flow of creating exhibitions. If one cannot ride the currents, we might end up being overwhelmed and swallowed by the situation. For me, this was something that kept coming up throughout the project. Change is inevitable. As a curator, one must learn to be diplomatic and empathetic to the various stakeholders and actors in the process.

For me, one of the most rewarding challenges was translating the energy of the Philippines’ archipelago into an exhibition in Frankfurt. How do you think the design and atmosphere of the show itself carry that sense of movement, multitude, and flux?

Aside from curation, I definitely enjoyed the challenge and process of designing the exhibition. While serving as a curator of the exhibition is challenging enough, translating an abstract concept into a physical experience presents its own trials. I was particularly excited about designing an exhibition for the DAM because it is such an important cultural institution in Europe.

Architecturally, the DAM is a significant example of postmodern design by Oswald Mathias Ungers, having opened in 1984. Ungers’ Haus im Haus (“house in a house”) concept for the DAM, in which he famously inserted a white house within the 19th-century Wilhelminian villa, exemplified how the debate over merging the old and the new was central to postmodernism. I felt there was a lot of pressure to do the exhibition design properly, especially when dealing with an iconic space.

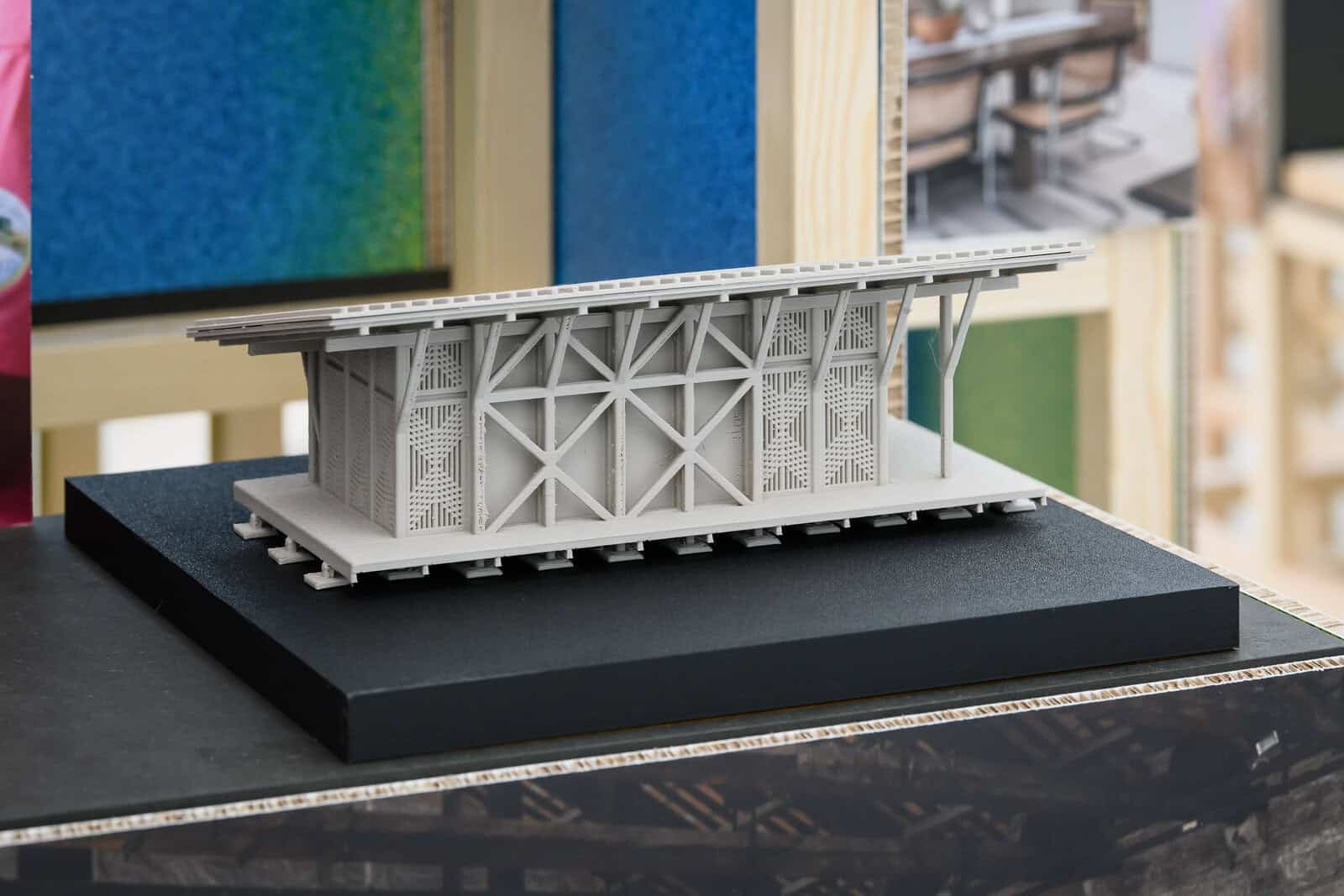

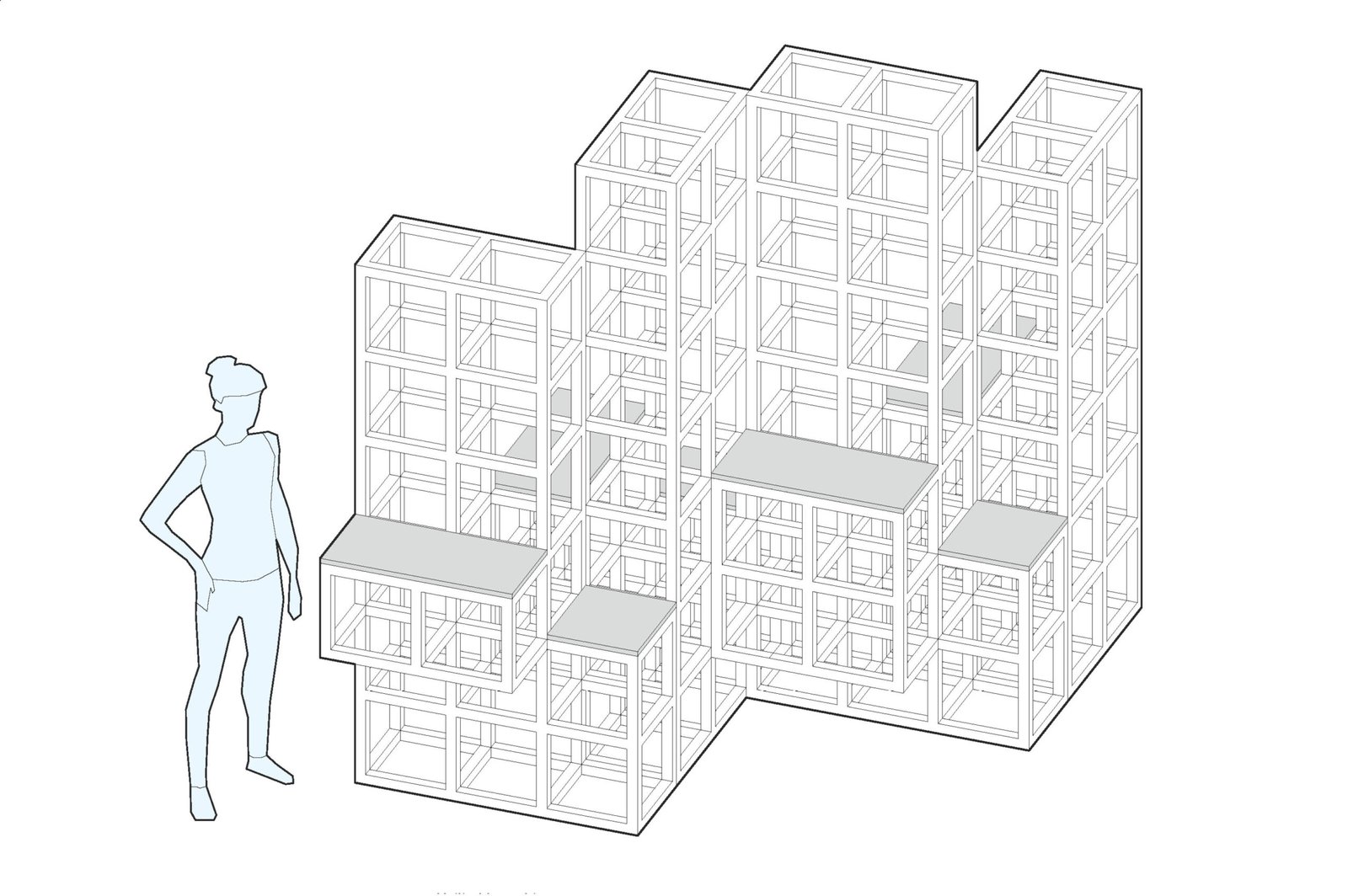

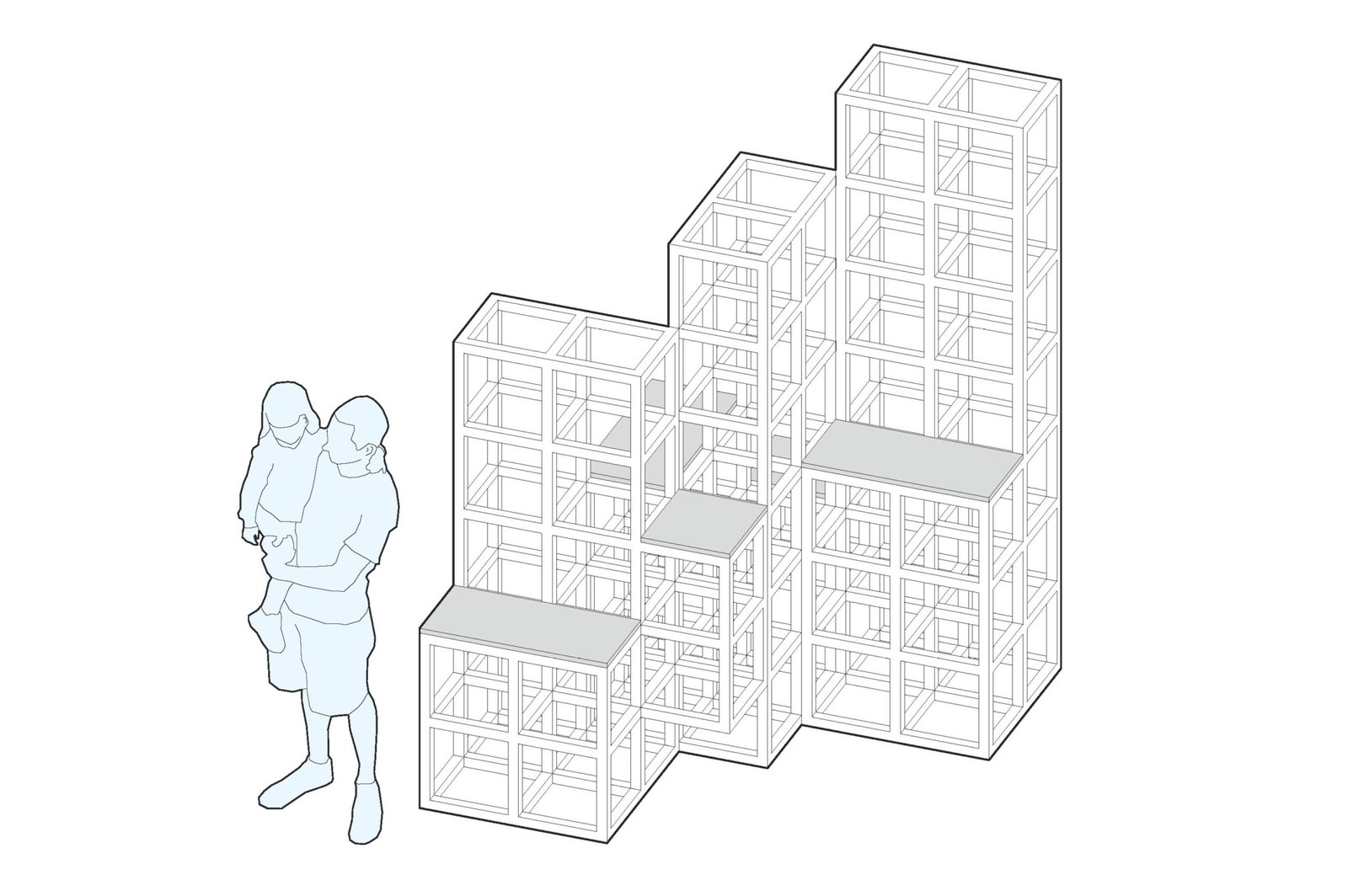

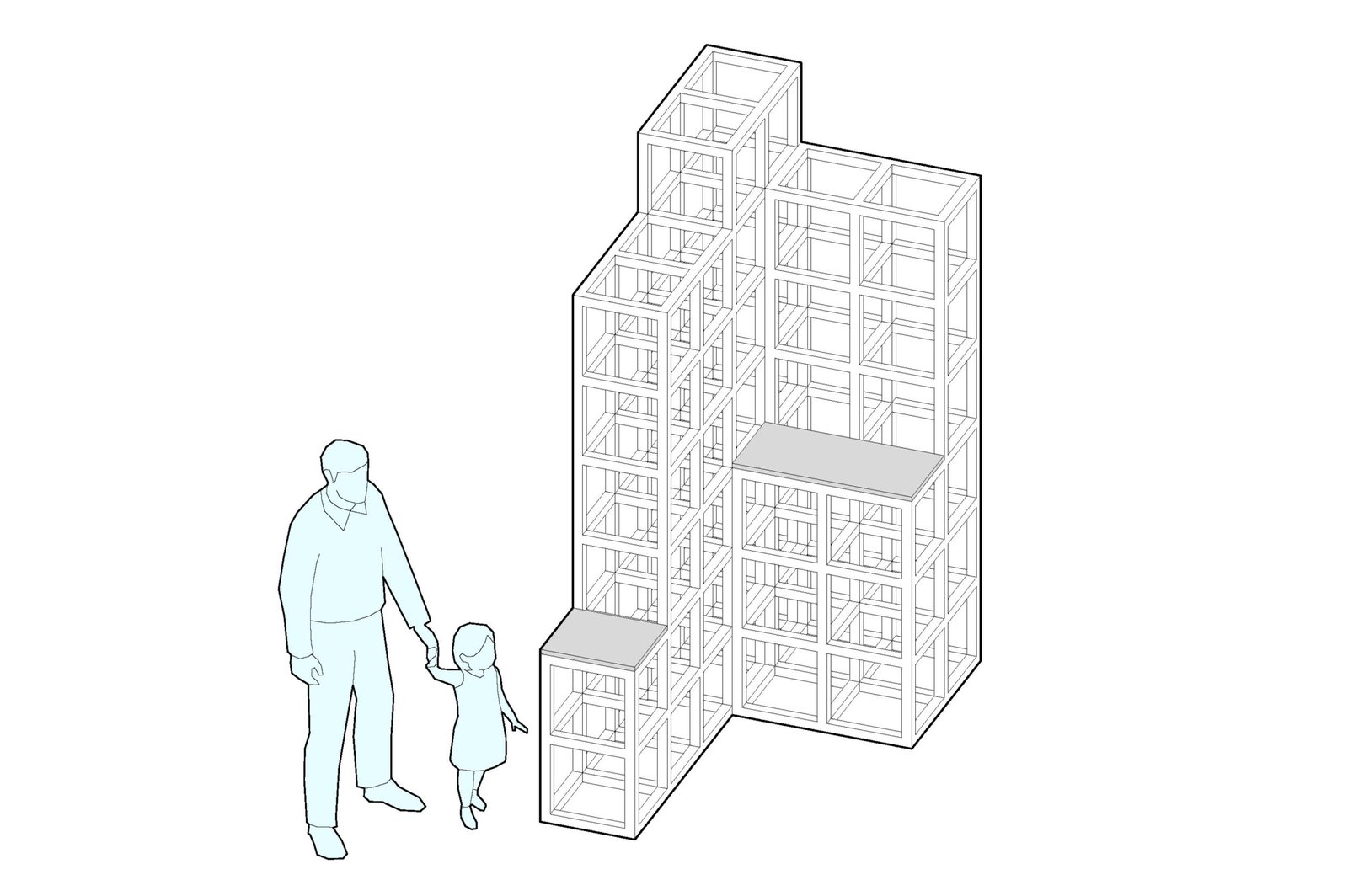

In conceptualizing the exhibition design, I was similarly reflecting on what it means to design something new within a canonical postmodern space. The third-floor exhibition space was bright and airy, bathed in light from the skylight above. I approached the exhibition design as simultaneously a homage and a contrast to O.M. Unger’s design, which is this white cuboidal house set within a historic shell. I wanted to translate the idea of water currents within Unger’s pristine orthogonal space through zigzagging wood-frame structures, emulating an ocean wave in a pixelated, grid-based form.

I intended to capture the dynamic movement without necessarily using literal wave forms as a vessel for framing the exhibit. At the same time, I envisioned the exhibition design contrasting with the white space, intentionally allowing the wood-framed structure and the displayed images’ colors to stand out. I shifted the grid of the exhibition display system at a 45-degree angle relative to the museum’s overall grid to acknowledge the logic of Unger’s design while also subverting it. With undulating pixel-like forms, the exhibition design was meant to represent the multitude of voices, contexts, and stories, all flowing and connecting within the space. One therefore not only sees but also feels the idea of flux.

If someone were to ask why they should see Sulog now, in this moment, what would you say makes the exhibition urgent or timely, not just for Filipinos but for anyone curious about architecture’s role in our interconnected world?

Seeing the Sulog exhibition at this moment gives the visitor a sense of what contemporary Filipino architecture is. While it does not purport to present a comprehensive or exhaustive set of examples of contemporary Filipino architecture, it does attempt to offer a glimpse of architectural possibilities embedded within a globalized world.

The exhibition argues that what we consider Filipino architecture today, along with contemporary architecture practices in other parts of the world, is not an isolated object set within geopolitical boundaries but is part of an extensive network of people, places, and processes that transcends time and space.

Contemporary architecture connects within and outside each country. This also means that we cannot truly define Filipino architecture by simply looking inwards, but rather see it as part of this global network. Maybe we should not even try to define what Filipino architecture is, because doing so sets the limits and boundaries of what it could become. I want visitors to leave the exhibit with renewed vigor and a belief that architecture can contribute positively to society and the world. Hope becomes the undercurrent in all of the stories in the exhibition.

After working together on Sulog, what’s the one thing you’d insist I never forget if I go on to curate another exhibition?

It was such a wonderful experience collaborating with you and Peter Cachola Schmal, the Director of DAM, on this project. I learned so much from you. I hope you take away from this exhibition that the curatorial process, as well as its implementation, is relational and situational, much like the exhibit’s theme. One must go with the flow, even though sometimes it feels like we are tumbling through the turbulent seas. Like the water currents, whose ebbs and flows might seem unpredictable, we must learn to ride out the waves. •

Sulog: Filipino Architecture at the Crosscurrents is on show at the Deutsche Architekturmuseum till January 18, 2026. You may download the exhibit catalogue for free here.

Sulog: Filipino Architecture at the Crosscurrents

Exhibitors

Aya Maceda, ALAO

Anna Sy, CS Architecture

Charlotte Lao Schmidt, Soft Spot

Bianca Weeko Martin

Christian Tenefrancia Illi, KIM/ILLI

Laurence Angeles, MLA at Home

Leandro V. Locsin Partners

James Acuña, JJ Acuña/Bespoke Studio

Sudarshan Khadka and Alexander Furunes, Framework Collaborative

Andrew Sy, Bryan Liangco, and Clarisse Gono, SLIC Architecture

Gabriel Schmid, Studio Barcho

Dominic Galica, Dominic Galicia Architects

Daryl Refuerzo, Studio Fuerzo

Jorge Yulo, Jorge Yulo Architects and Associates

Justin Xaver Guiab

Edwin Uy, EUDO

Amata Luphaiboon and Twitee Vajrabhaya, Department of Architecture

Benjamin Mendoza and Annabelle Mendoza, BAAD Studio

Micaela Benedicto, MB Architecture Studio

Buck Sia, Zubu Design Associates

Jasper Niens and Rick Atienza, Studio Impossible Projects

Keshia Lim, San Studio Architecture

Jason Buensalido, Barchan + Architecture

Ronnie Yumang, Balika Rammed Earth

Ray Villanueva and Rhalf Abne, Kawayan Collective and Kawayan Design Studio

Arts Serrano, One/Zero Design Co., and First United Building

Carlo Calma, Carlo Calma Consultancy

Neil Bersabe, BER SAB ARC Design Studio

Installation Design and Models

Bien Alvarez

Christian Lyle La Madrid

Matter

Photographers

Bien Alvarez

Jar Concengco

Patrick Kasingsing

Greg Mayo

Michael Reyes

ES.PH

Xu Liang Leon

Scott Woodward

Ketsiree Wongwan

Miguel Nacianceno

Chris Yuhico

Alex Furunes

Andrea D’Altoe

Federico Vespignani

Natalie Dunn

Arabella Paner

Nicholas Calcott

Tony Luong

Kurt Arnold

Tabitha Fernan

Film

Bien Alvarez

Jar Concengco

81 Happened Media Co.

Micaela Burbano

Martha Atienza

Isaiah Omana

Construction Layers

NCCA – PAVB

Exhibition Designer

Edson Cabalfin

Nicholas LiCausi

Art Direction

Patrick Kasingsing

Graphic Design

Switch Asia Inc.

Marvic Masagca, exhibit graphic designer

Juliana Marie Reyes, catalogue designer

Juvalle Tinao, art director

Miguel Llona and Marikit Singson Florendo, production manager

Catalogue Editors

Edson Cabalfin

Patrick Kasingsing

Writers

Bianca Weeko Martin

Timothy Augustus Ong

Steffi Sioux Go Negapantan

Angel Yulo

Dominic Galicia

Caryn Paredes-Santillan

Joseph AdG Javier

Proofreader

Danielle Austria

Deutsches Architekturmuseum (DAM)

Peter Cachola Schmal, director

Mario Lorenz, deserve, production exhibition

Wolfgang Welker, registrar

Bernadette Krist, model restoration

Brita Köhler and Anna Wegmann, PR

Exhibition Printing

Inditec

Exhibition Fabricator

Herstellung Holzinstallation

Schreiber

Catalogue Printer

IndexDigital

Philippines as Guest of Honor at The Frankfurt Book Fair 2025

Project Visionary

Hon. Loren Legarda

Senator, Republic of the Philippines

PHLGOH Core Team

Patrick Flores

Karina Bolasco

Riya Brigino Lopez

Charisse Aquino-Tugade

Flor Marie “Neni” Sta. Romana-Cruz

Kristian Cordero

Ani Rosa Almario

Nida Ramirez

Exhibitions Coordinator

Mapee DZ Singson

Communications

Karen Capino

National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA)

National Book Development Board (NBDB)

Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA)

Office of Senator Loren Legarda