Interview Patrick Kasingsing, with Gabrielle dela Cruz

Images Aerne Architects & Associates Co., Ltd.

Hi Martin! Welcome to Kanto. When the pandemic took over the world in 2020, it inevitably led to widespread changes in how we perceive and design our built environment. We are now slowly emerging out of the pandemic; how did COVID-19 redefine what being future-ready and sustainable is in the field of architecture?

Martin Aerne, director, Aerne Architects & Associates Co., Ltd: I think there are three main aspects to point out. The first one is that we need to make sure that we are flexible. Staying flexible is not just about having a similar answer should this happen again in the future—our homes will have to become much more than just a place to live.

The second aspect concerns touchless innovations. Not so much at home, but definitely in public areas. Many people would probably relate to this, but even now that things are slowly getting back to normal, we still hesitate to touch buttons, knobs, or the like in public areas. I think that needs to change and that’s where technology will come in, maybe more than architecture.

The third aspect, I believe, would be intensifying outdoor living and working. It is important to recognize that we have spaces, especially where we work, where we have plenty of natural ventilation. This is absolutely possible considering the climate in our region.

In our own office, we practice working outdoors 60 to 70 percent of the time. We have large sliding windows open and it is only when necessary that we close them and turn on the air conditioning.

Since you mentioned your office and natural cooling, I’d like to ask: have you gotten the chance to work on mid-rise or high-rise developments in Cambodia? For single-story or two-story homes, passive cooling and cross ventilation are more or less easier to implement. The taller a building gets, the more difficult or the more complex it is to adhere to tropical or passive cooling strategies. How has your studio dealt with something like that, since you don’t want to be too dependent on air conditioning for energy-saving purposes?

It’s actually the opposite. We harness much too little the potential of mid or high-rise buildings in terms of natural ventilation. The higher we go, the more wind we have. Of course, the wind can become too fierce, so you have to be able to adapt, to close off when necessary. But on a lower level, we have so much development that the wind is stagnating. But as soon as you go higher up, you have much better ventilation, less dust, and fewer mosquitos.

I see. In the Philippines, we have extreme versions of every weather condition, except snow. We experience extreme wind, extreme rain, extreme heat…

Because of that, it’s important that what we design and what we build is not fixed. It must be flexible enough so that you can open up or close off following the weather and even the mood you desire.

I agree with your observation that buildings need to be ready for these possibilities. Especially with climate change, where the weather patterns aren’t fixed anymore… Sometimes the summer season arrives a bit later or a bit earlier.

If we cannot adapt, then it would be like going into a sauna bath and then not being allowed to get out anymore. As long as you decide when you go in and when you go out, a sauna bath could really boost your health and immune system. It’s the same as how we live and how we work, we need to be able to choose the right setting for the moment.

A pretty apt metaphor… Now, for my next question, I’m sure you’re aware of this. Sustainability is in everyone’s mouth. However, as a topic, it is also replete with a lot of misconceptions and generalizations. What would you say as a conscious sustainability practitioner are essential points vital to a person’s proper understanding of sustainable design?

The truth is…to become truly sustainable, we have to tackle a lot of factors and consider a lot of aspects. We often tend to look at one or the other, but the one or the other is never sufficient. It’s a rather complex task.

I believe that one aspect that we often miss out on is that it’s not just about technology, or how we build, but it’s also about how much we build. It’s about a redefinition of luxury. If we simply develop the discipline to reduce the use of electricity and water as well as material goods, then it’s kind of a restriction of life. But if we review our views on what’s really valuable, what leads to true happiness, and come to the learnings from the old masters…then we can find deep satisfaction with much less. Desiring and delighting in the precious little would also help us become more sustainable, instead of us getting stuck in the never-ending want.

The second thing is the reduction of air-conditioned space and the use of the wonderful climate we have here in Southeast Asia. I agree that sometimes it’s too hot and sometimes it’s too cold, but for the large part, it is very agreeable. I come from Switzerland, where the cold period is very harsh and long. You cannot imagine how much I enjoy the tropical climate in Cambodia even after 21 years.

With regards to what you said, that “it’s not just about how we build, but it’s also about how much we build,” I’m suddenly reminded of the building standards that we have now such as LEED. Would you say that the proliferation of these building standards is both beneficial and detrimental to people’s perception of what sustainable architecture is and can possibly be? Because now it’s becoming like a convenient checklist and a marketing tool to easily market new buildings as ‘green’ or ‘sustainable’; We’ve seen in the cases of some certification standards, some don’t really measure up to real-world realities or are incompatible with the regions they are applied in.

I would say that LEED considers a lot of relevant factors already. It’s not just a simple checklist. I used to work with EDGE which is easier to implement but less comprehensive. But whatever current certification system we apply, I don’t believe we will end up with a totally sustainable city.

We need to develop an informed and reliable sensorium for what is sustainable, an intuitive, tactical know-how when it comes to energy, material, and how to design smartly, a sensorium that makes us feel and see where we go over unsustainable limits. We cannot make it for another millennium with our current awareness.

When developers or architects try to market their work, they always use the terms “future-ready” or “future-proof.” Research reveals that they’re not the same. As an architect, what would you say is the difference between building future-ready and future-proof buildings? And, in your opinion, which should one aim after? Should you aim for future-ready buildings or to future-proof buildings?

Terminology is always a bit tricky because it is a matter of how you interpret it. And I don’t think it’s fair to say it means only this particular thing, because it’s a word and it can comprise a lot.

However, when I hear the term “future-proof”, then I feel we are going a little too far. Because nobody knows the future fully. It’s always about predicting from where we are and what we can understand now so that we can anticipate what the future might look like and where the potentials and risks are.

It has much more to do with being very well-informed and responding as responsibly as we can. So instead of using labels and creating categories that make us simply satisfied or help us in marketing, we need to focus on being well-informed and acting at the top of our abilities and with integrity.

Whether what we produce will be future-ready or not, nobody can guarantee. But I believe the key to being as ready as possible, is to think and act integral and long-term.

“Desiring and delighting in the precious little would also help us become more sustainable, instead of us getting stuck in the never-ending want.”

Right. So for my next question… Adaptive reuse is often considered one of the most effective ways to promote sustainability in the built environment. It is also arguably one of the hardest to implement, especially in very heavily built-up urban areas. Speaking from experience in the Philippines, a lot of developers will often demolish and start from scratch because it’s more often than not cheaper to do it that way. I don’t know how it is in Cambodia, but what’s your studio’s stance on this? What conditions or considerations would you say can make adaptive reuse more palatable to developers? Who are the key players and shareholders that are vital to getting these conditions and considerations in motion to make adaptive reuse much more attractive?

Fortunately, we have clients that are family businesses, who develop properties and keep them. These developers are usually very open to thinking in ways that allow the adaptation of the building in the future for little cost and with minimal impact on the tenants. But for developers who are building to sell, this is a different story.

However, generally in Cambodia, and I think largely so in the region, we build regular frames and fill them with non-load-bearing walls, which permits future reorganization of buildings without tearing them down. This is very different compared to Central Europe, where almost every wall of a residential building is load-bearing and inflexible. Also, installations in Cambodia are largely independent of the structure, different from Switzerland, where many services are embedded in the concrete slab. This separation between structure, spatial divisions, and services within Asian structures allows it to be more conducive to adaptation.

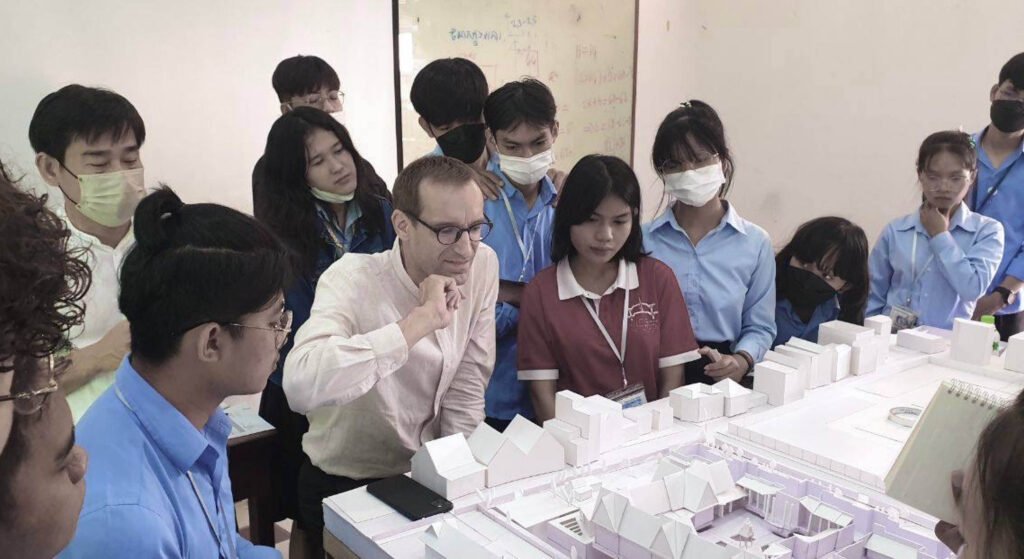

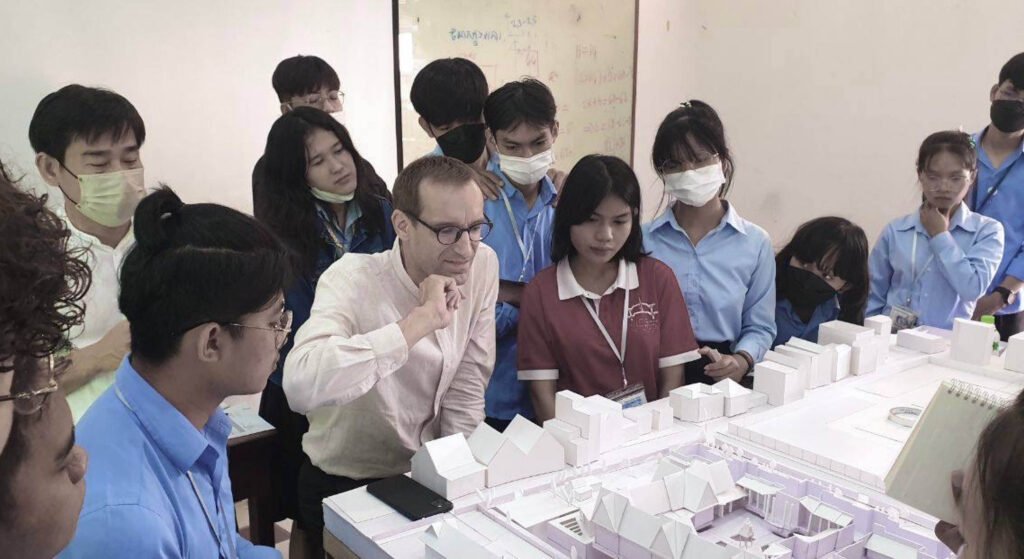

You’ve been teaching at the Royal University of Fine Arts in Cambodia, under the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism for 10 years now. Sustainability is now increasingly, as it should be, integrated into building requirements nowadays. Do you support its integration into the curriculums of architecture and allied programs in universities to aid a wider and more foundational understanding of the subject? Are there pros and cons to this?

Absolutely. We must integrate the subject of sustainability into the curriculum. In our university, this is already the case, though without much impact on students’ designs as of now. Architecture is a multidisciplinary undertaking, and it remains a challenge to devote sufficient time to all aspects. Hence, sustainability studies might be more effective if conducted as a specialized track so that one can really master it and then advise others who have not had enough time to put their head around the subject. This however is already happening. We are having our first local consultants for green architecture, even though they might not have had extensive training as in other parts of the world.

We’ll now hone in on your chosen country of practice. You’ve been living in Cambodia for 21 years. How is the experience of practicing in the country thus far? And in terms of sustainable design, how easy or how hard is it to get a client to buy in for it?

Cambodia is a very young market, still in the process of recovery from its turbulent past. This country has two sides: On one hand, there is a lack of skills, components, and technology that restricts design, on the other, it is still largely an open field, home to a generation that is up and coming, very eager to experiment. Few regulations and low standardization give architects room to explore new ways forward, translating visions into reality, as long as no high technological requirements are needed.

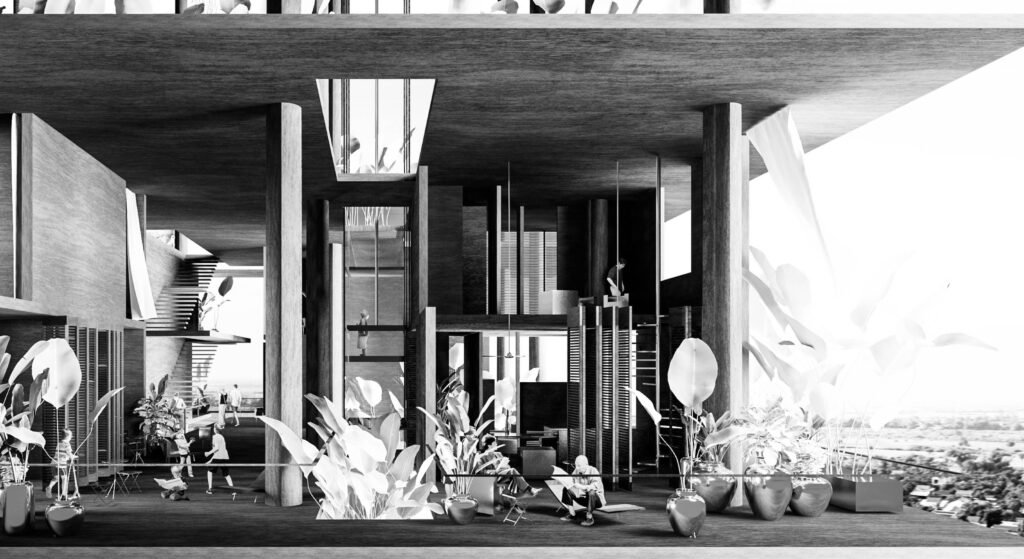

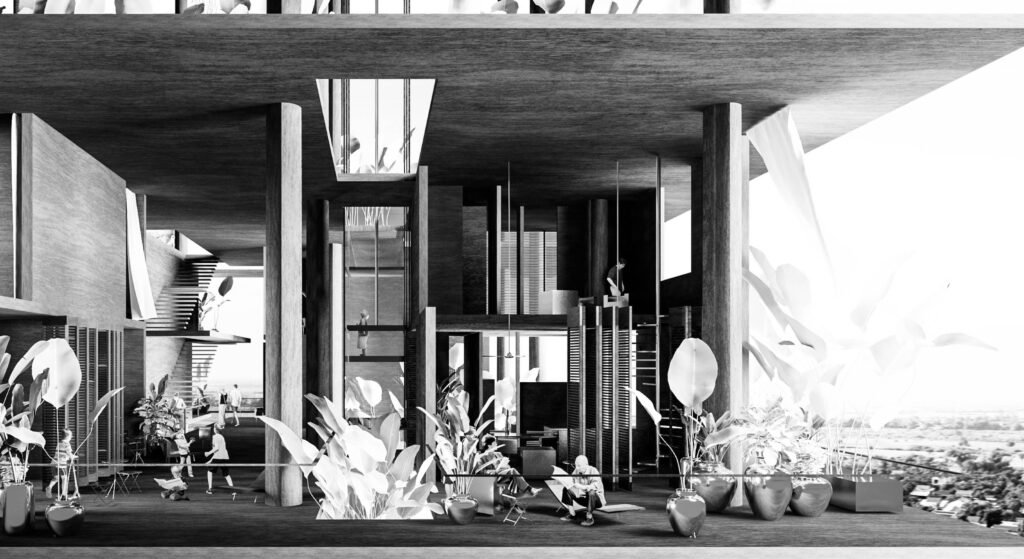

Since we are on the subject of practice in Southeast Asia… you presented an intriguing residential concept for a sustainable community for your talk for American Standard’s Design Catalyst L!ve webinar. For the benefit of our readers who may have not seen the project during the live stream, can you walk us through your concept?

The project’s premise is anchored on extensive outdoor living and the minimization of climatized indoor space even on higher floors. It consists of a number of minimal duplex units gathered around a communal, village square-like access area. On the outer layer of the building, large verandahs extend the units with generous, private outdoor spaces, providing panoramic views, whilst connecting the users with greenery, breeze, and birds. It also helps deflect excess light, heat, and rain and protects the rooms that lay behind.

The shared square comes alive when neighboring kids come to play when people open their homes and allow visitors a glimpse into their kitchen and dining, when a breakfast table is put out in the open, and when the elderly observe life on a chair in front of his or her unit… it is up to the inhabitants to bring this square to life.

The key element for this is not to put a hundred households together as this will result in a clamor for privacy and the outdoor space will be dead. You need this magic number of maybe seven to twelve households sharing that space so that they can get to know each other, knowing builds trust and trust leads to safety, as one looks out for the other. However, we must make sure that everybody can regulate the level of openness and privacy they desire depending on their mood, their current relationship with their neighbor, on the time of the day, and so on. Spatial flexibility is key. This is how you build communal relationships. You cannot force it, but you can stimulate it and facilitate it.

I think that your speculative concept is very much compatible with Southeast Asian culture. The family is a major aspect of every individual’s life. There are a lot of households here where even the grown-up kids still live with their families, as opposed to the Western model where it’s very different. So the concept you just explained is definitely executable here.

On this quest to sustainability, we must include Man himself. Not merely because he depends on an intact environment, but because he is an integral part of nature. Hence we are not to put our focus only on the impact the built environment has on the planet, but also on how the environment shapes the mindset and behavior of the user, how it impacts both a person’s physical and emotional well-being in the long run.

Last question, Martin. What does the future of architecture look like for you? And how do you think present realities like climate change innovations, the advancement of AI, and 3D printing, are going to affect the field’s evolution?

These trends and more will definitely affect the field’s evolution. I don’t know exactly in what ways, and maybe it’s not even that important to know, but it will be exciting as it brings new opportunities. Though technology will shape architecture and assist us in ways yet unknown, architecture will always remain a domain not only controlled by rational and objective processes of optimization but an expression of personality and identity, the creation of a unique atmosphere and human experience, a realm of relationship with one another and the environment.

When it comes to the look, I believe it will look very different and in some cases extremely fascinating. When it comes to technology, I believe we will have to see huge changes in how we build. Just recently, when I looked out of my hotel room window and I see these concrete loads being dropped and being pulled up, I felt like we are so outdated in how we build, evident every day. Compared to a mobile phone or a car, building technology is so behind.

I can well imagine a future with high-rises coming up, built with laminated bamboo structures, prefabricated with extremely elaborate, idealized shapes with the help of modern technologies, much faster and much lighter than ever before, but by no means less intriguing

I think we’re still being held back by the construction technologies that we’re still availing. I guess that’s what’s been holding back the potential of buildings to be more elaborate, flexible, efficient, and more.

It concerns not only the single building but urbanization as a whole, more so due to a rural exodus with no end in sight. When I look at cities such as Bangkok, it saddens me to see how humanity managed to put itself into a desert of concrete. I do dream that the cities of tomorrow, especially in hot climates, will rather look like an urban forest or an urban jungle, where nature and the artificial merge and temperatures drop to agreeable levels. •

This exclusive interview was made possible by American Standard

One Response