Interview Miguel Llona

Images Sidewalk Labs

Tell us about recent innovations Sidewalk Labs has developed to address urban challenges.

Eric Jaffe: Sustainability, affordability, and fair economic opportunity were among the toughest challenges facing cities before COVID-19 hit. They remain pressing today. No single innovation can address complex urban challenges, but Sidewalk Labs has either launched or is developing a few innovations we think can make a meaningful difference in these areas.

One innovation is called Delve, a master-planning product that empowers urban development teams to discover designs that help achieve their project objectives, such as more housing units, leading to denser, more sustainable development.

Another innovation is called Mesa, an easy-install kit that helps commercial buildings cut energy waste and costs, comply with local energy-efficiency regulations, and improve tenant comfort. Mesa improves sustainability and is also an affordable solution designed for smaller, older buildings that don’t have big budgets to improve energy infrastructure.

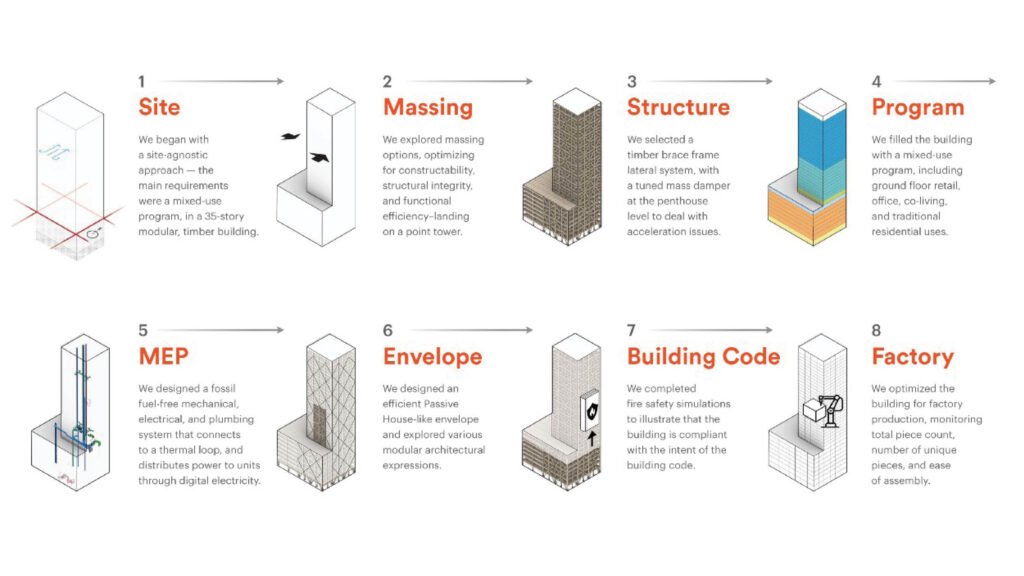

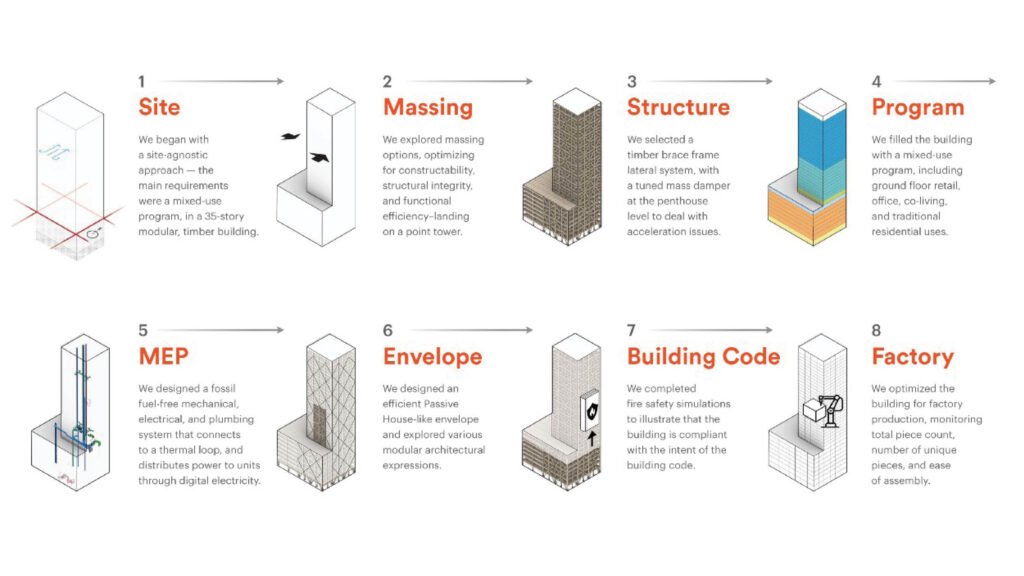

A third innovation we’re currently developing is an offsite construction approach that can deliver high-quality mass timber buildings for more sustainable living and working.

What significant differences are there between ASEAN and Western urban planning and how people commute?

I’m no expert in ASEAN urban development. I do think there are strong examples in ASEAN cities of effective public transportation networks, housing models, and digital infrastructure. Singapore, in particular, is a leader in these areas that Western cities often look to for guidance.

Are Sidewalk Labs’ innovations applicable in ASEAN cities? How might you employ them here?

Sidewalk Labs is based in the US, but we work with development teams in cities around the world. For example, the team behind the Delve product has worked with developers in Asia. The challenge of designing neighborhoods that meet the objectives of both developers and communities is a global one.

Based on your work with Asian developers, what are the best modes of transport for people in the ASEAN region? Why?

Cities are defined by their density, and the challenge of density means moving the most amount of people in the least amount of space. That’s why public transportation is the most efficient form of urban transport in ASEAN cities or any other. Walking and cycling are also highly efficient uses of shared space in cities, and are the most sustainable transport modes. But relying on walking and cycling requires mixed-use development that puts homes, jobs, and services all close to each other. That’s where good planning comes in.

The most equitable cities offer a balanced network of transportation options rather than focusing only on car use. Balanced mobility expands job opportunities for residents and reduces the social costs of car use (such as pollution and traffic fatalities).

At the start of the interview, I mentioned some of the challenges facing cities: sustainability, affordability, and economic opportunity. Bikes help address all three. They are an extremely climate-friendly transportation, they are far more affordable than cars. And if cities create the proper infrastructure — including protected lanes and bike-share access — bikes can connect workers to jobs.

You wrote an article saying walkers, cyclists, and public transport-riders are happier and more satisfied than drivers. What have been the most effective moves governments have made to reduce car reliance, particularly in cities planned for cars (Metro Manila being a prime example)?

Behavioral studies routinely find that driving commutes are the most stressful type of commute, given the demands of traffic on a person’s attention. Reducing car commutes requires a comprehensive approach, including smart pricing policies (such as congestion pricing), smart land use principles (such as mixed-use, transit-oriented development), smart infrastructure investments (such as transit expansions that outpace highway expansions), and smart street design (such as fewer parking spaces and dedicated bike + transit lanes).

It’s true that it’s very difficult to change a city’s transportation culture once a car-first system is locked into place. But the approaches mentioned above can start to rebalance the system: pricing, street design, infrastructure, and land use. These changes will not happen overnight and require significant long-term government focus.

My home of New York City is a great example of a place that became much more friendly to cyclists over the past 10-20 years. New York did it by significantly expanding bike lanes, launching a bike-share network, and reducing vehicle speed limits. There is still a long way to go, but progress is possible.

Folks here say our intensely hot summers and typhoon seasons are why our cities aren’t more walkable and bicycle-friendly. What is a good response to that?

Again, I can’t speak to the situation in ASEAN countries specifically, but in general, extreme weather can indeed play a role in someone’s decision to walk or ride a bike. That said, I would also note that the global rise in extreme weather events is all the more reason to shift away from car use urgently. The longer we rely on gasoline vehicles, the worse we are damaging the climate.

What flaws in the way our cities are designed has the pandemic exposed? What trends do you see in city planning in anticipation of future pandemics or other black swan events?

Absolutely, the pandemic exposed some flaws in urban design. In US cities, for example, downtown office districts emptied out entirely, calling into question the wisdom of single-use districts. Are central business districts simply an outdated relic of the industrial age? In the future, cities should plan for mixed-use developments that can provide both residential and commercial uses and be flexible enough to change with demand and trends.

COVID-19 has certainly changed life in cities (and everywhere). One thing that’s stuck with me, at least for US cities, is how the pandemic exposed a tremendous divide between the knowledge-sector workers who have the luxury of working remotely and the service-sector workers who continued to show up in person to do their essential work. Great cities provide economic opportunities for everyone. That means local governments in the US must do a better job protecting service workers through public investments, social safety nets, small business support, and minimum wage increases. Private companies must also do their part to reduce the wage gap and ensure fair pay for all workers.

I’m very excited by the street design changes that caught hold in many cities during the pandemic. There are definitely opportunities across local street networks to reduce the amount of space dedicated to parking and driving and return some of that space to other transportation modes, local businesses, or other neighborhood uses. I’d like to see cities reimagine street design on a network basis, too, with car traffic confined to fast-moving perimeter streets and interior streets prioritizing walking and cycling. •

Kanto.com.ph is a proud co-presenter of Anthology Festival 2021. This interview was produced in support of the Festival and its organizers, WTA Architecture and Design.