Interview Patrick Kasingsing

Art Clement Laurencio

Hello Clement, scribbling anything right now?

Clement Laurencio: Hi Patrick! How did you know? Let me just wipe away the graphite from my fingers before I get it all over my keyboard!

Recount to us how you discovered your talent for architectural illustration.

Clement Laurencio: Perhaps ‘talent’ is an overstatement… How about ‘interest’? (Though I must say thank you, it is very humbling!) I had always enjoyed drawing ever since I was a child. Though it wasn’t until architecture school that I began drawing buildings and spaces, both real and imaginary. Towards the end of my final year in Architecture, I finally gathered enough confidence to do the final drawings of my project, Arachne’s Lair, by hand. It really was thanks to my tutor, Mani Lall, with whom I now have the utmost pleasure of teaching as a Design Tutor at the University of Nottingham. From then on, I always had a set of pencils on hand!

The architecture you depict is often fantastical and puzzle-like. Tell us what attracted you to this depiction of space, and how it is evocative of you as an architect and an artist.

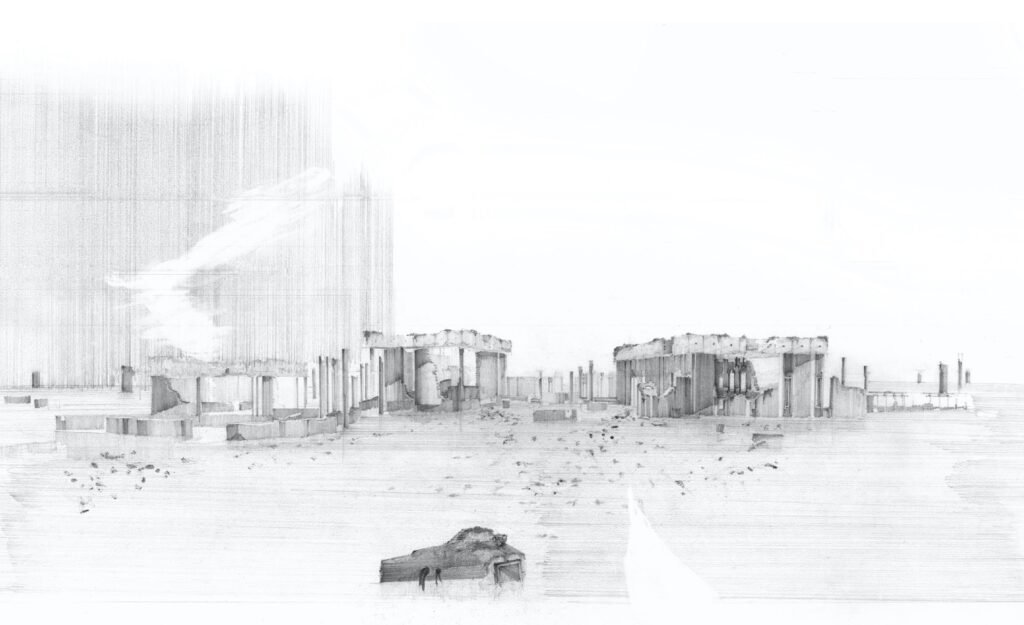

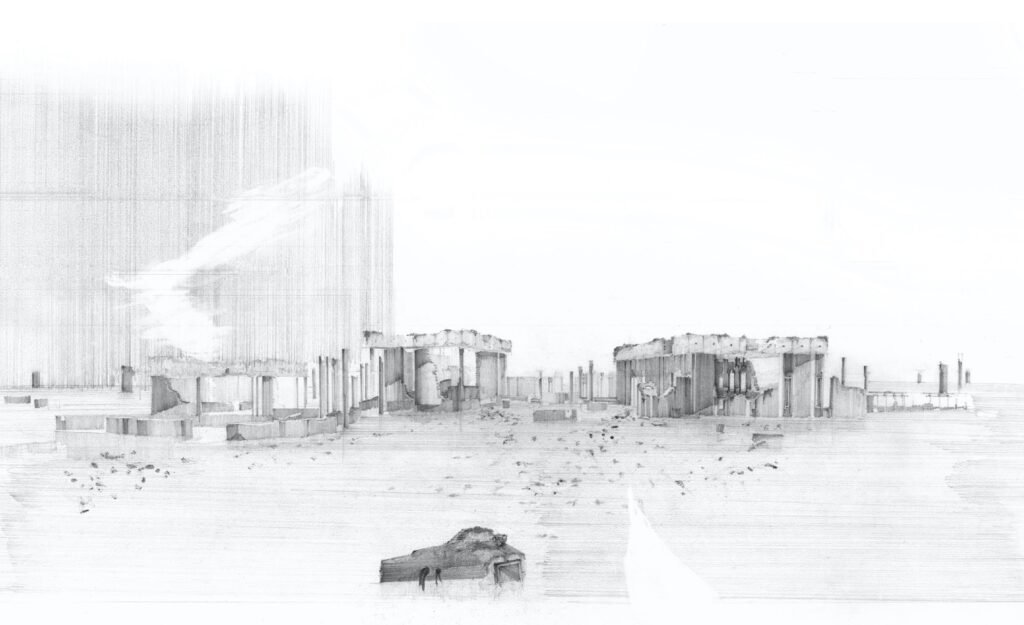

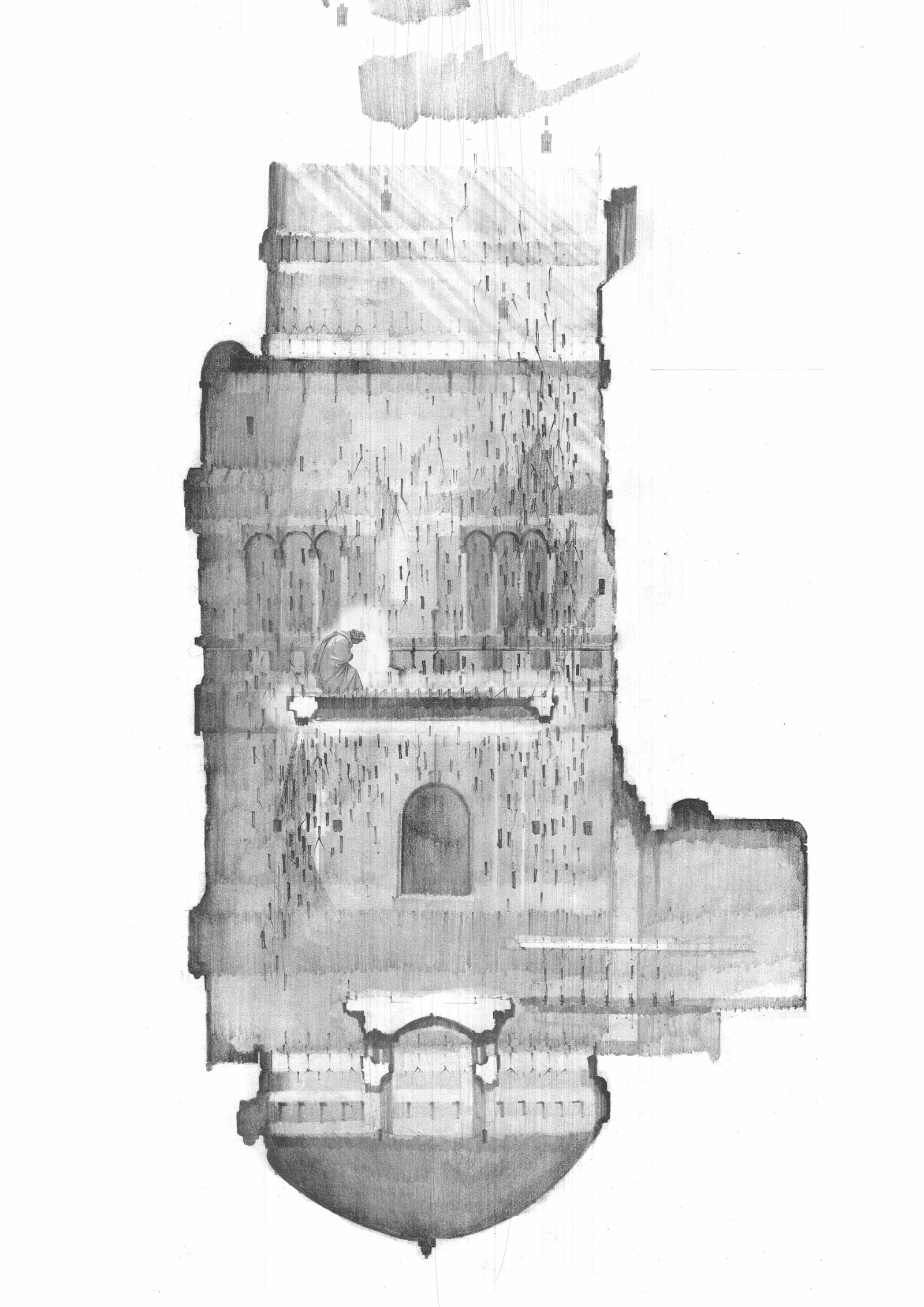

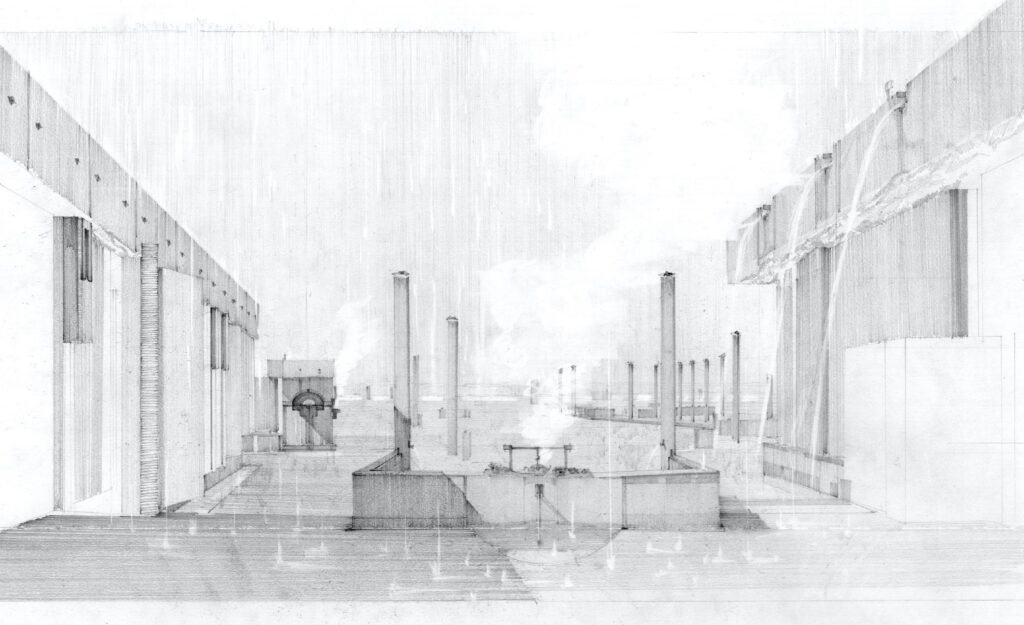

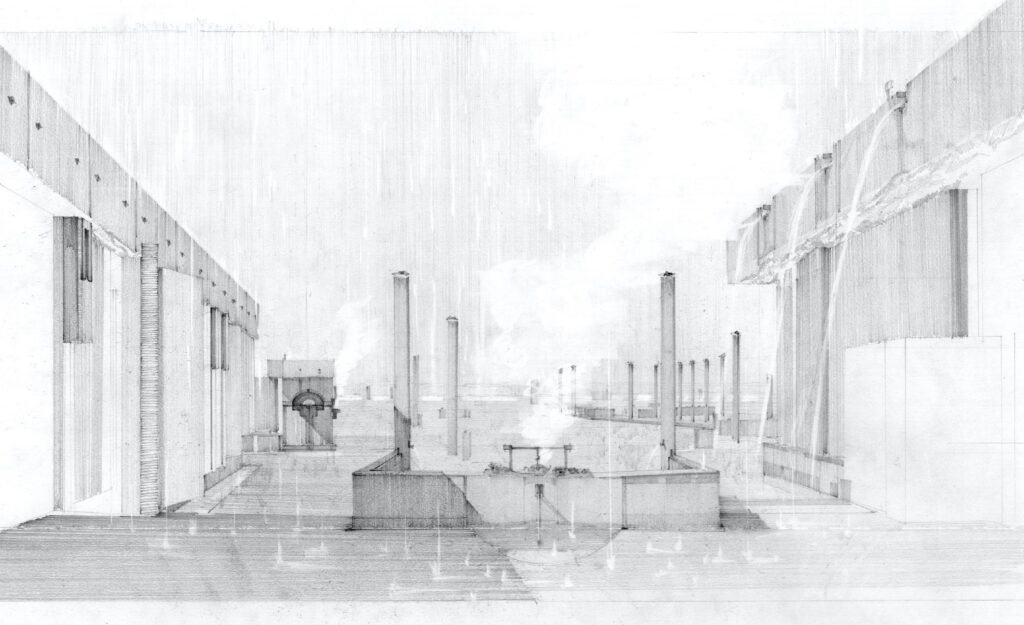

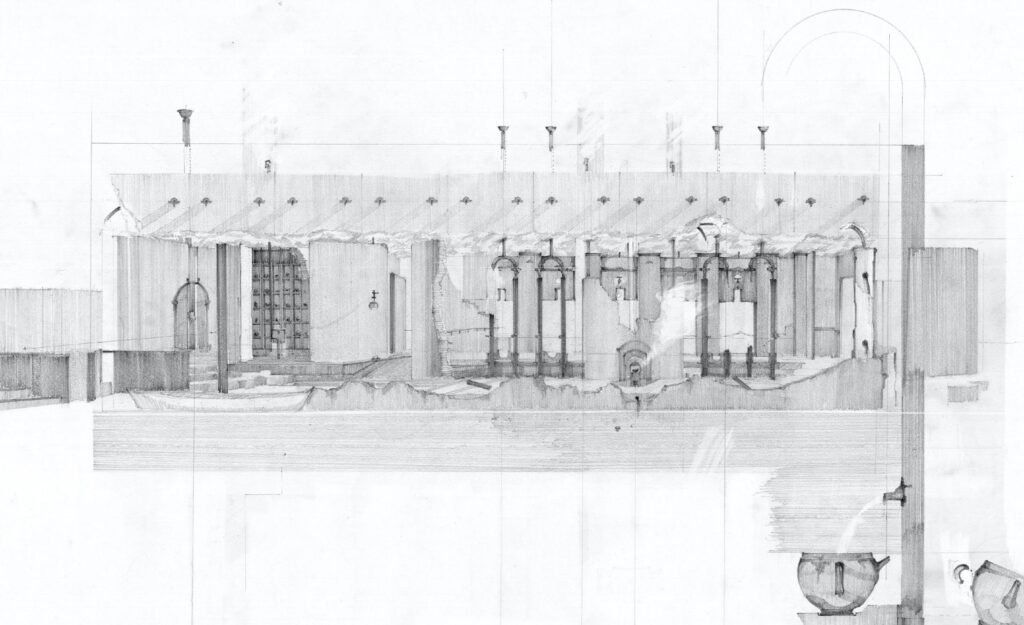

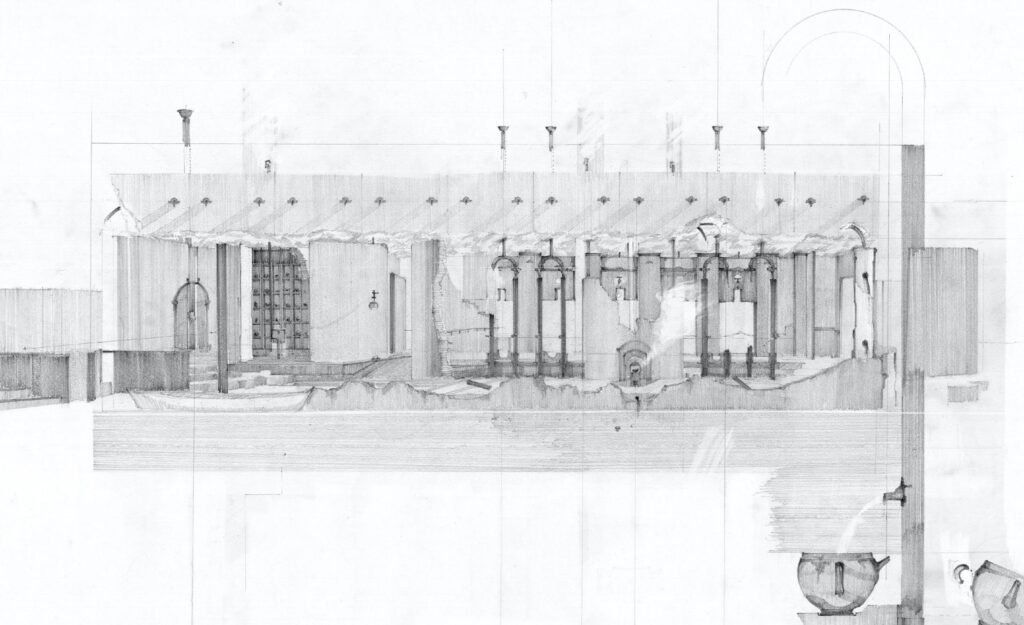

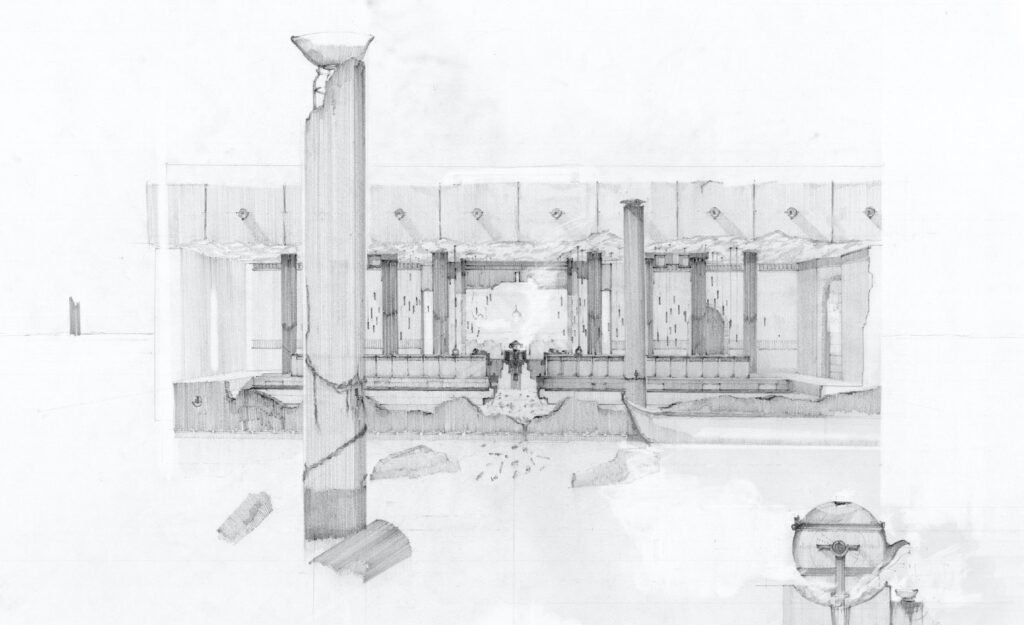

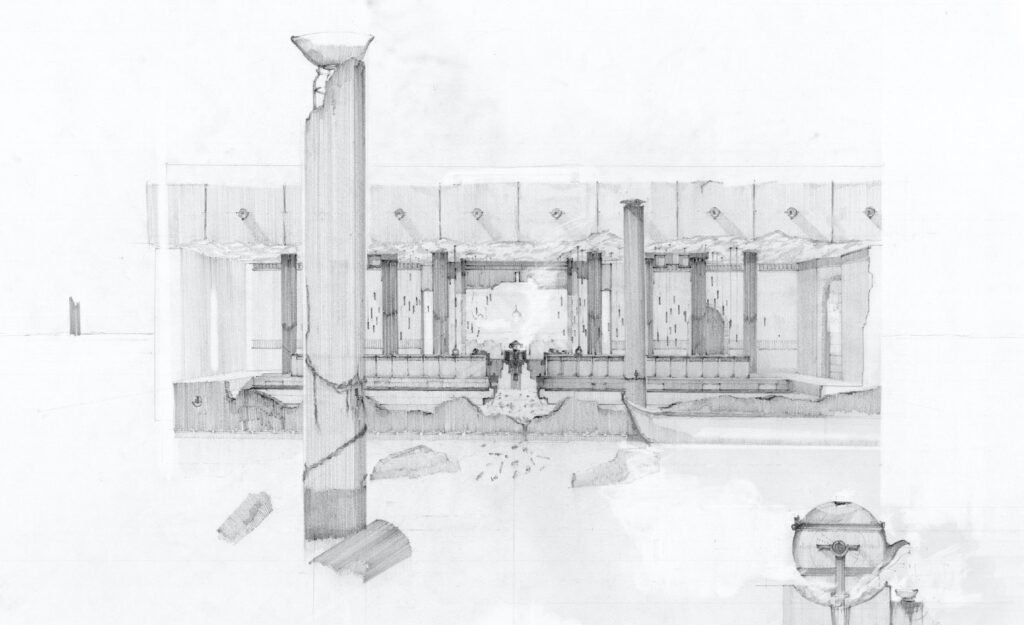

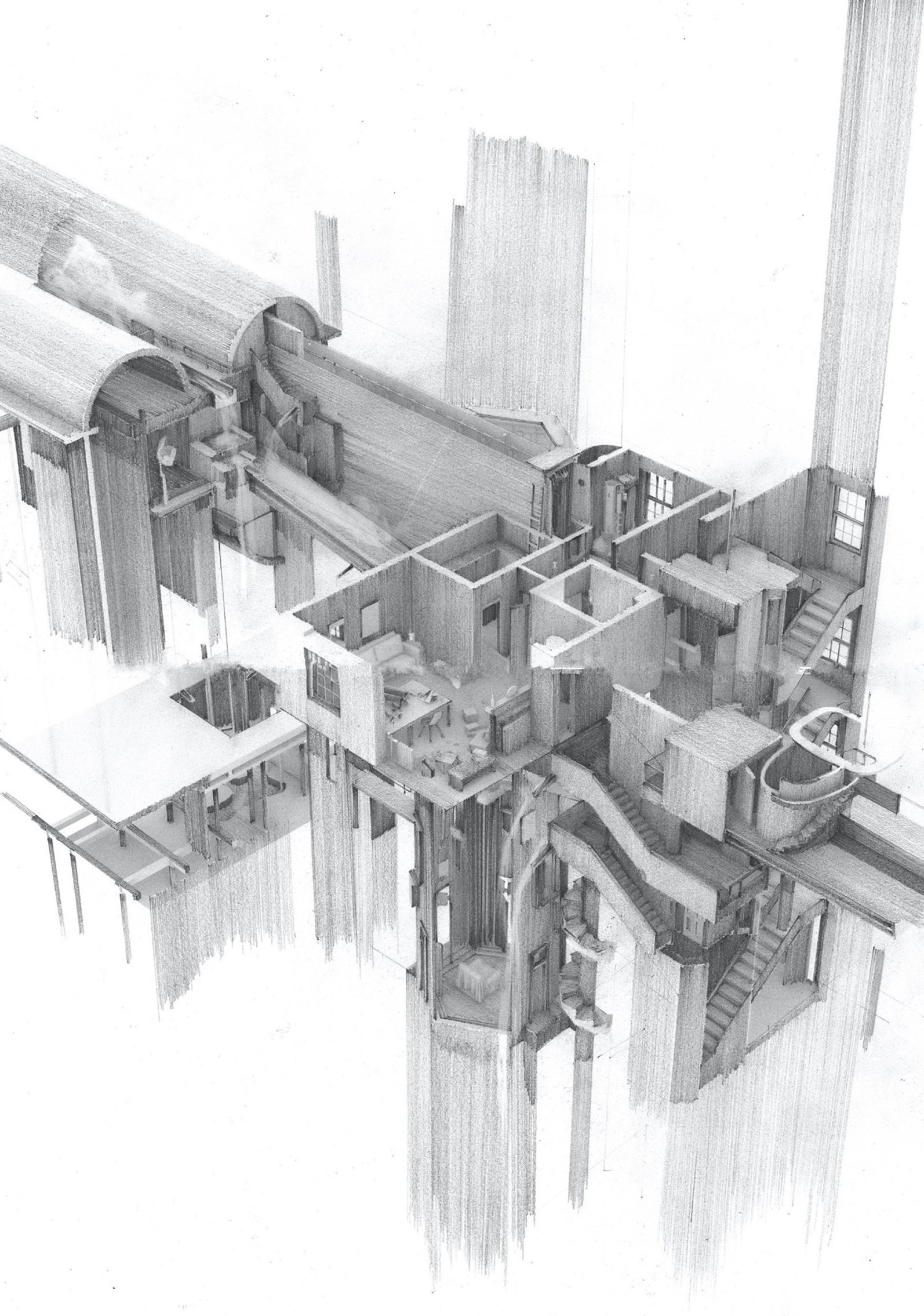

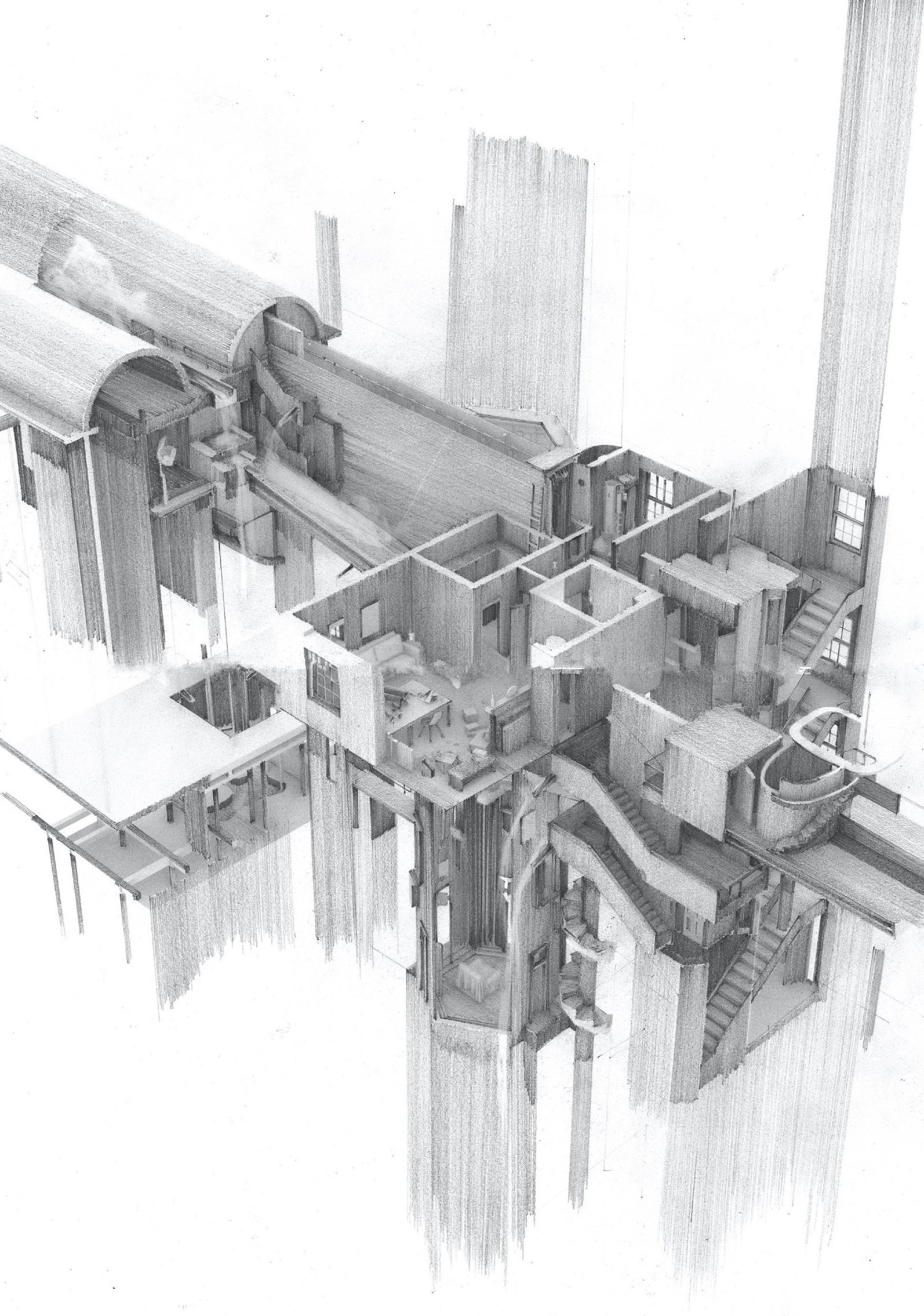

Maybe it lies in the actual process of drawing. Rather than merely representing a building, I always try to create drawings that place the project in the world and the narrative in which it exists. For example, Apartment #5 deals with spatial memories, which appear as flashbacks or fragments. Pavilions for Conversation is set in a speculative future after global sea levels rise and appear in a state of ruin. Arachne’s Lair is set within the ruins of the Bishop’s Palace in the City of Lincoln in England, while an underlying narrative gives life to the spaces.

Arachne’s Lair (2016) All the drawings were done in the late hours of the night, and I liked to keep my room dark with only a desk lamp illuminating my paper. This hasn’t changed since.

Pavilions for Conversation (2019) The participants’ movements in the experimental tea ceremony were translated into the spaces within the pavilions. You can see photographs of the ceremony on my website.

Tell us a bit more about Arachne’s Lair.

Clement Laurencio: The City of Lincoln is iconized by Lincoln Castle and Lincoln Cathedral. While these colossal structures are still an imposing presence today, we have lost the sounds, voices, and colors that used to resonate within these giants. Every passing moment, tones, auditory manifestations, and life of the City are recorded and inscribed into a spider silk strand, harvested from the Golden-Orb Weaver. Hiding within the Cathedral’s shadow, embedded within the ruins of the Old Bishop’s Palace, Arachne’s Lair will become a new beacon for the city, where the Tower continually transforms, as the Tapestry is archived within the Palace.

I try to use drawing more than just to realistically depict a building or space. I’m more curious to explore the intangible. Say, the atmosphere and feeling of a place—the poetics of space. Also, there is never a final full stop when drawing by hand. It is quite exciting when the drawing itself is in a perpetual state of continuation, never truly finished, and leaving enough place for others to dream and interpret it for themselves.

How has your flair for illustration affected your appreciation of architecture? What insights about the field are revealed to you by sketching it as a subject?

Clement Laurencio: It definitely deepened my appreciation. I have always gravitated towards the hand-drawings and even etchings by architects past and present: Carlo Scarpa, Lebbeus Woods, Shin Takamatsu, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Perry Kulper, Peter Wilson, and Thom Mayne, to name only a few.

Some of them have built works, which are fascinating to see, translated from paper to the built environment, while others have created such beautiful and enticing drawings that you imagine being real. Regardless of whether the projects were made or not, the hand drawing conveys such elegance, atmosphere, and aura. The paper is a world in itself. You can see where the architect has poured his/her efforts and thoughts.

Fundamentally, those drawings are spatial. So, inadvertently, we place ourselves in that space. We meander through it, we imagine grasping the handrail or looking through an opening that has been carved out for us, and we subconsciously inhabit that space within the drawing—we go on a daydream.

You mainly draw with graphite. What attracted you to this medium? What is it that you want to ‘subvert,’ as you say on your site, with the usage of ‘analog materials’ such as pencil and paper?

Clement Laurencio: Graphite has always been a medium of wonder to me, perhaps because it is so versatile. You can create something as ephemeral as the trace of a shade or something as intense as a darkness that hides something deep within its shadow. It also reflects light, so it engages the viewer to reposition the drawing. It is a medium that is subtle and elegant yet harsh and profound.

From what I’ve seen in architecture schools around the UK, the general trend these years has been that final images for projects are rendered using digital means. Some great projects make use of VR and take new software to incredible ends! Projects making use of the pencil for the final renderings aren’t many, and understandably so. After all, today’s architecture firms use computer renderings as the workflow is faster, more efficient, and presents something closer to reality.

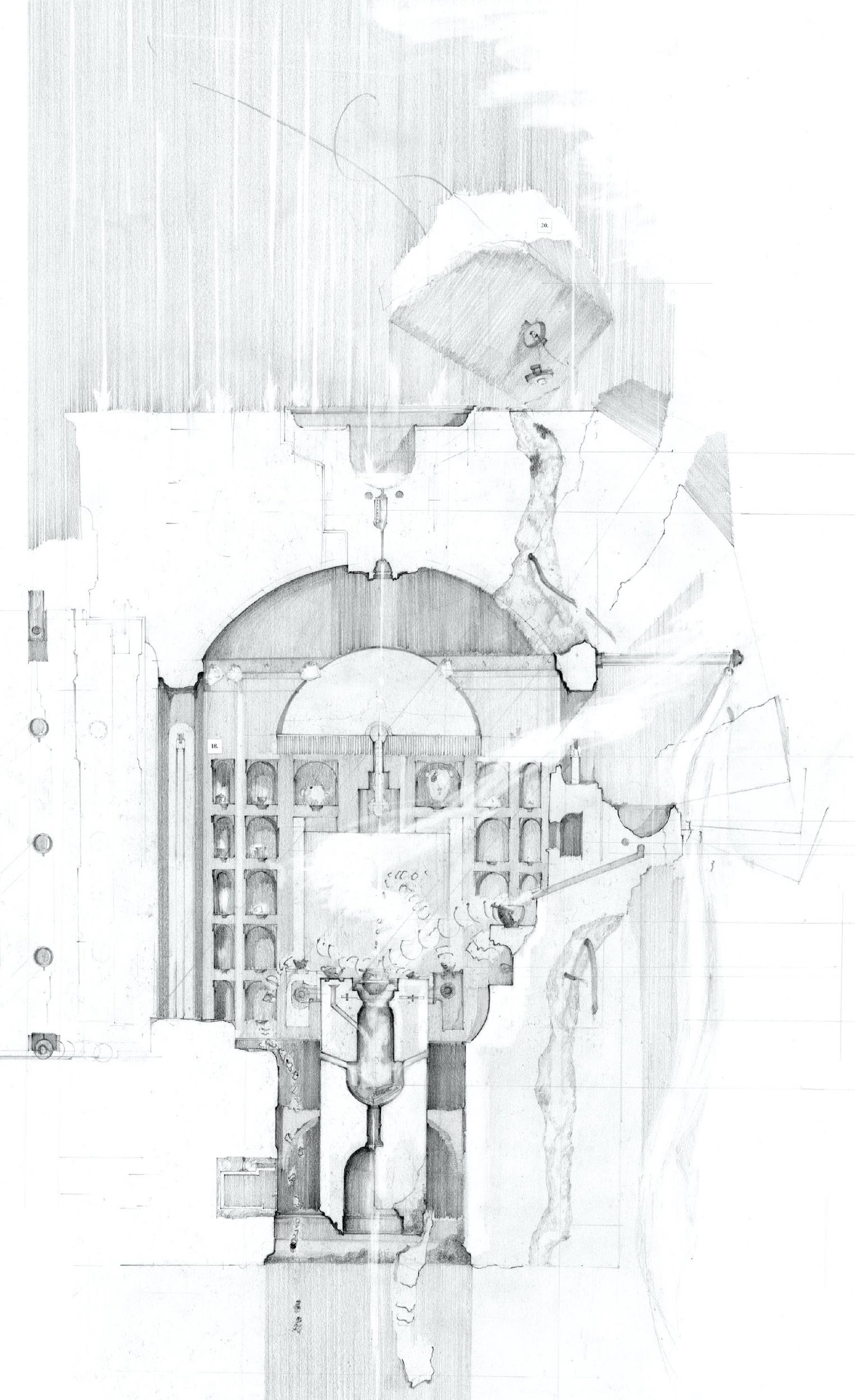

Furthermore, progress in the field can only be achieved by keeping in line with our times’ technological advances. While I, too, use computer software to develop my projects (the drawings for Apartment #5, for example, are drawn over a 3D computer model), I try to keep the pencil drawings up to the final stages of the project to convey how I imagined the spaces in the first place.

What is your process in conceptualizing your spatial explorations? Are your illustrations the product of spontaneity, or are they meticulously planned projects like the field they depict? Perhaps a bit of both?

Clement Laurencio: A bit of both, I think! The drawings for Arachne’s Lair (2016), Pavilions for Conversations (2019), and Apartment #5 (2020) are the culmination of a university project, each spanning a year. It begins with a response to an architectural brief, which is within the unit’s scope of research. Then, site investigations, spatial iterations, material exploration, and more are gathered and explored.

These exercises are essentially treated as architectural projects with the same rigor required of professionals by the Architects Registration Board (ARB) and the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), the accreditation bodies for architects in the UK. After all, architecture schools in the UK are moderated against ARB/RIBA criteria. So, the projects must adhere to the learning outcomes before being awarded a degree and accreditation.

After a year’s worth of development and refinement, it is then time to produce the projects’ final drawings. This is where I can pour my imagination, dreams, and thoughts on paper. They are all done within the last month or so before submitting the design project portfolio, and it is an exciting time where I can let my mind delve within the spaces. Though, as I am drawing, some spontaneous happenings do occur! For example, for Pavilions for Conversation, I imagined two people sharing a cup of tea over the stone hearth and how, over time, you would see the traces of where the teacup wore away the stone underneath. In Apartment #5, the water from the tap disappears into the pipes, only to re-appear as a cascade that feeds the pool reflecting Balkrishna Doshi’s Sangath studio (an homage to the memory of visiting the Sangath gardens back in February). Those spontaneous moments are what make drawing such a fun process!

Your architectural illustrations are also an exercise in storytelling. What kind of stories or narratives do you often tell in your work? Is there an overarching theme or personal philosophy that governs them?

Clement Laurencio: You’re quite right in saying that, Patrick. Each project is designed with its own narrative in mind, and it exists in its world. They are almost like novels or films. In cinema, each film creates its own rules, by which their worlds can exist. Because of this, the viewer is willing to suspend disbelief and inhabit that space beyond the screen. In many ways, I try to achieve a similar framework to draw people into the world of my drawings.

Perhaps, rather than an overarching story or narrative, I try to create spaces that are fundamentally atmospheric and beckon to be inhabited. I enjoy drawing spaces where one can feel a certain intimacy with them. I often don’t have many people in the drawings because I would rather let the viewer themselves walk through those spaces. I try to make it so that people may feel the warmth of the sun-kissed tiles, run their hands through the weathered scratchings left behind on the stone, or hear the gentle sound of raindrops hitting the floor. The spaces in the drawings become silent places of contemplation and reflection.

I think it may be because I’ve always gravitated to churches when I was a child. To me, they were stone caverns, elemental and silent, where you could hear the echo of your footsteps, and the warmth of the candles bathed the interiors in soft light. That’s the atmosphere and intimacy I try to convey in the drawings, regardless of the project.

Is there a pressing issue or perceived lack that your drawings aim to address, depict, or float to the public’s awareness?

Clement Laurencio: Simply that architecture can still be a poetic craft. Today, speed seems to be the governing ethos for design. We live in cities in which life is fast-paced. I just want to offer a brief moment of pause from all of this cacophony through the drawings themselves. A small moment of escapism from the wider world, for one to re-center and focus once again.

In this frightening period of the lockdown during the pandemic, travel has become difficult, unsafe, and in many cases, restricted. Locked in our dwellings, we long to escape to a past before the lockdown, far away from here. For now, we are left with our memories and photographs of times and places past.

Apartment #5 in London curates spatial experiences from my recent voyage to India. Set both in real space and imaginary space, the project seeks to re-create those atmospheres and spatial conditions of the places alive in my memories. However, the following thoughts come to mind: Can the dwelling become a ‘repository’ of curated spatial memories from places that can no longer be accessed? A way to re-experience those times and places within the space of the apartment? In this period of extended lockdown, what has time done to my memories?

Over time, we unconsciously curate our memories: discarding, splicing, and merging moments. We re-create the spaces we have committed to memory into a construct. We tend to recall the visceral feelings of particular moments and the spaces surrounding them. But the passage of time opens up the possibility for the mind to select discrete fragments of those spaces in our memories. They are compressed, stretched, and non-sequentially placed in an alternate time and space to the one our body presently occupies. Time appears anachronistic. Feelings of the past resurface in the present. Spatially, mentally, and physically, one is in two places at once. This project is an attempt to spatialize this anachronistic quality. The memories are rekindled by manipulating scale, forced perspective, and atmospheric phenomena. However, they may become embellished, corrupted, and re-imagined, becoming a labyrinth of fallacious memories—a repository of times and spaces past and an escape from our current reality.

Architecture and illustration have long had an inseparable relationship. Still, the computer-generated depiction of architecture is the status quo in visualizing unbuilt designs. What can architectural illustration best depict about its subject that renders cannot?

Clement Laurencio: Honestly, it is understandably so. The way our industry works calls for computer-generated depictions, which are much faster to produce and so much more precise. This is great for the office workflow to adhere to deadlines and multi-million-dollar projects, so the clients and the investors know precisely what they are paying for!

However, what is missing from these computer-generated depictions is the hand of the designer. While there are incredible renderers who can create hyper-realistic images, there is something so enticing and intimate in the line that has been drawn by the author. Behind it hides intention, thoughts, dreams, speculation. It can be a process towards an idea, where after every line, the intangible idea that had started in the mind then pours onto the tangible paper. On one hand, when one is looking at the computer render, the mind knows it is looking at a construed reality. On the other hand, the pencil is elusive enough to make room for the client’s imaginations and dreams as well!

A few notable firms and studios are eschewing computer-generated renders for collages, hand-made renderings, and other artistic means of depicting spaces. Why do you think this is happening now?

Clement Laurencio: Indeed, many are going back to fun and simple collages to communicate a sense of space, color, and composition. Particularly when meeting the clients, the quick sketch’s advantage is that it conveys the idea or the intention very quickly. After all, that is how architects from the pre-digital era communicated and convinced clients of their vision.

Have you been drawing more during the lockdown?

Clement Laurencio: Most definitely, with more time spent at home, I’ve found myself drawing more! I think drawing has become an act of meditation as it is an act of creation now.

The Soane’s Lost Room triptych was born out of the lockdown and somewhat evolved from the Apartment #5 drawings. The drawings imagine what Soane’s collection would have looked like if he were to collect fragments of our more recent architectural past. However, the spaces are actually the corridors, staircase, and room in my home. I imagined it as Soane would have imagined his own dwelling—a labyrinth of spaces, where maquettes of famed Modernist works, built and unbuilt, line the corridors.

Editor’s note: Knighted in 1831, Sir John Soane, one of the top architects of his day and professor of Architecture at the British Royal Academy, bequeathed his home and an extensive collection of architectural models, painting, sculptures, and antiquities to the British government to be preserved as a museum.

What has the present pandemic revealed to you about architecture’s relationship with its users? Would you say the field has met its mandate to shelter and protect its users well?

Clement Laurencio: This pandemic has affected the entire world and made it obvious to the whole architectural community that now is a time for change in our industry. Even those who aren’t in the field of architecture have begun using their built environment differently. We are hyper-aware of what we touch. We stand and walk further apart from one another. Hospitals around the world have had to expand the number of beds and patients under their care, and spatial organization has been the crux to enabling doctors and nurses to perform their actions efficiently and effectively. School desks now take on the function of personal-space bubbles, and the home has doubled as the workplace. Spatial composition and architectural intervention are two of the many vital tools needed to fight against the spread of the novel coronavirus and future unknown viruses.

The study of architecture wouldn’t have been possible without the illustrations and artistic depictions that documented its existence and memory. Your architectural drawings do the same, in that it both encapsulates and is a response to the realities and conditions you move in. But let’s look to the future this time: What architectural legacy do you wish to impart to future generations both as an architect and an artist? How would you describe the spatial narrative you want to tell and to be told to future generations?

Clement Laurencio: While the graphite will one day fade away, my only hope is to inspire people through my drawings. Just as I was inspired by the drawings of great architects, if I can inspire someone to begin drawing, look into architecture, or create something of their own, then for me, that is the greatest thing possible. Hopefully, it then becomes a perpetual cycle, where they too would inspire the next person, and so on!

As for my architectural legacy, I suppose it is simply to convey that architecture is as much a poetic craft as it is a professional and pragmatic field and that architecture can be about spaces of calm serenity, atmosphere, and pause. Finally, through the architectural drawing, one can dream and invite others to share that dream.

What’s the most challenging surface you’ve drawn on?

Clement Laurencio: The blank paper before the start of a drawing is the most challenging surface and the scariest surface to draw on! •

More fantastical re-imaginings of architecture at @clementluklaurencio

3 Responses