Introduction and Interview Judith Torres

Images University of Northern Philippines

The moment of realization

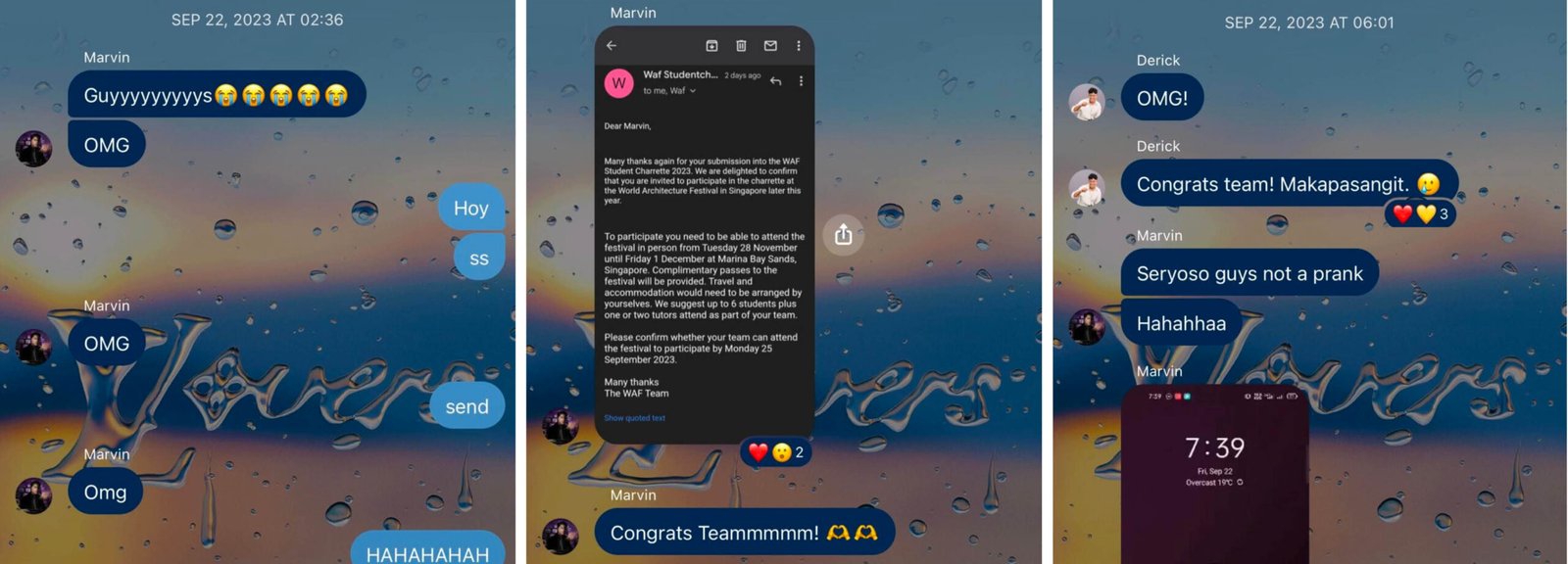

Trishia Mae Quiming’s phone chimed softly in the dark. Her heart skipped a beat as she saw Marvin Bayle’s name flash across the screen.

“Guyyyyyyyyys,” Marvin texted, followed by a string of weeping emojis, then, “OMG.” Trishia’s heart raced—she knew this had to be about their submission to the World Architecture Festival. Why else would Marvin be texting the team group chat at 2:36 AM?

“ss,” she replied quickly. Send the screenshot! she thought, joy and agony rising in her chest.

Another “OMG” popped up, followed by a third. Trishia typed back her laughter in ALLCAPS, feeling Marvin’s loss for words through the screen. Aaagh, the suspense.

Then, the awaited screenshot arrived—an email from the WAF Team congratulating them. They were invited to participate in the Student Charrette competition at the World Architecture Festival 2023 at Marina Bay Sands in Singapore.

Trishia’s room remained dark and quiet, a stark contrast to the storm of excitement in her. “I wanted to scream!” Trishia recounts. “But I didn’t because everyone was still asleep. I remember thinking to myself: Kaya pala talaga namin. It was a manifestation that anything can happen if you put your mind and pour your heart into it. And it starts with the courage to try.”

Forming Team UNP

During the pandemic, John Derick Dasugo, a seasoned senior design architect at Cadiz International with experience in Jakarta, Bali, and Dubai, felt the pull of home. He decided to return to his roots in Ilocos Sur, start his own practice, and impart what he’d learned by teaching part-time at the University of Northern Philippines.

Fast-forward to May 2023. Browsing on Facebook, Dasugo stumbled on Kanto’s post about the WAF Student Charrette competition. Marvin Bayle, one of his enthusiastic students, had also seen the post. Their shared interest sparked a pivotal conversation. Recognizing the opportunity for real-world experience, Dasugo encouraged Marvin: “Since you’re graduating next year, I think that would be a great way to, you know, stress yourself more, hehe, before you graduate.”

Unlike the highly competitive WAF Building of the Year,the Student Charrette did not require an entrance fee, making participation accessible. “Kaya medyo matapang kami sumali,” Dasugo recalls. “That’s why we were quite bold to join.”

As the Design 7 and 8 instructor, Dasugo was well-acquainted with his students’ capabilities. “I was their instructor during their 4th-year Design class. We had been working together for more than a year before joining WAF,” Dasugo explains. His selection process was not about academic performance but the unique skills each student could contribute. The criteria were clear: strong concept-generation abilities, drafting and 3D modeling expertise, and the ability to present confidently in front of an international jury.

Dasugo chose four students and instructed them to choose four teammates to max out the allowed eight members. The four chose classmates they knew they could count on to contribute. “The project required collaboration and teamwork, so the eight needed to work well together,” says Dasugo.

University of Northern Philippines team members:

- Marvin G. Bayle

- Anthony C. Delgado

- John Mark Niño C. Fabie

- Jade G. Gacusan

- Jaimeeh Khariz Paet

- Gianne Paula A. Peralta

- Raiven Ameri D. Ponce

- Trishia Mae P. Quiming

- Tutor/Mentor: John Derick R. Dasugo

Stress on stress

The timing for submitting the Charrette proposal was far from ideal. The team was under immense pressure, with only a week after exams to submit their proposal. “It was finals kasi sa school, so it was hell week,” Dasugo recalls.

Fortunately, the submission didn’t require a full design, allowing the team to focus on crafting a compelling proposal. They brainstormed in coffee shops on potential projects that embodied “Catalyst,” the theme WAF provided.

Dasugo divided the team of eight into three smaller groups, each tasked with developing their interpretation of the theme. During this process, Trishia Quiming reflects on the team’s shared vision: “Our goal was to propose a small-scale project that has a huge impact. We thought a catalyst should be this: a candlelight that could spark an explosion of hope and change.”

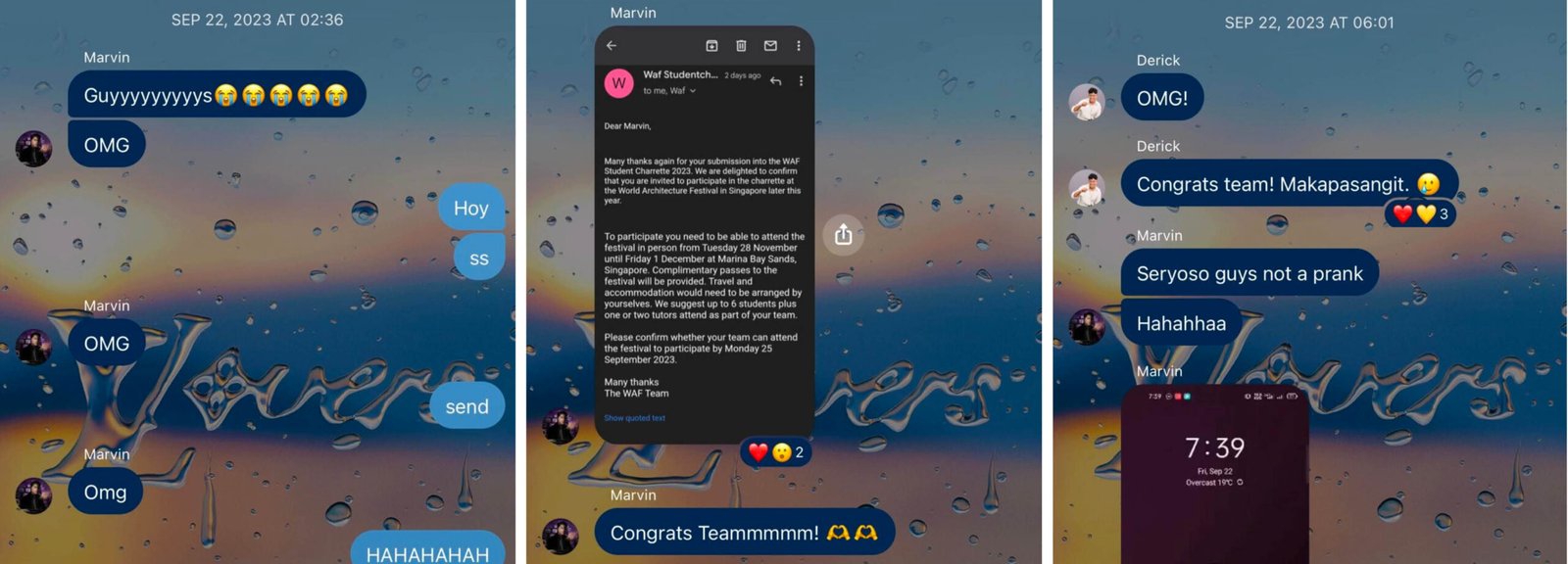

Concept Harmonization

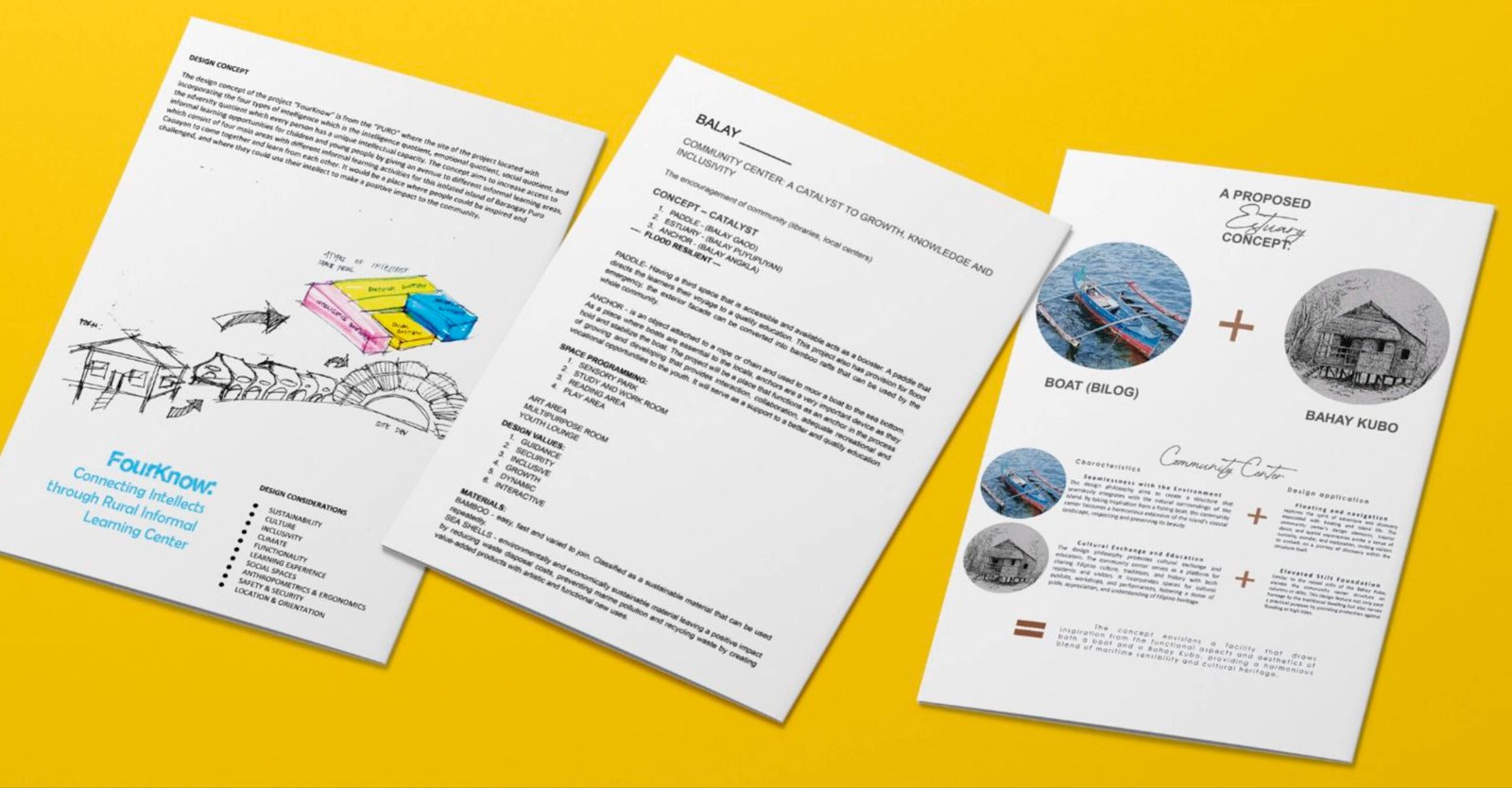

The independent ideas from each subgroup shared a common vision. They focused on community, inclusivity, and transformative change, which allowed them to merge the three seamlessly into one final concept, “Balay Arapaap” or House of Dreams.

Marvin Bayle details their thought process: “We considered the challenges facing the northern region of Luzon, specifically the historic city of Vigan. We asked ourselves: What problems have we encountered in this area, and what kind of architectural solution could be applicable? How can our design act as a catalyst for positive change?”

The project site

“After careful consideration, we focused on the national issue of quality education and chose an isolated barangay, Puro Island, in the Municipality of Caoayan, Ilocos Sur, accessible only by boat or raft. The educational institution in this barangay serves students from elementary to high school. However, unlike nearby areas or the city proper, this barangay lacks a ‘third space’ where children can enjoy and learn outside the formal school setting. By creating a third space for this isolated barangay, especially for the children, we could help nurture their dreams and unlock their potential,” Marvin adds.

Island adventure

During their first exploration of Puro Island, the team examined potential sites, guided by suggestions from the local barangay captain. The tiny island, nestled at the estuary where the Abra River flows into the West Philippine Sea, peeks just 4.2 meters above sea level. Its vulnerability to flooding and storm surges is a constant threat to the island’s 1,106 residents, of whom 26 percent are children and young adults—the intended beneficiaries of the team’s project.

As they walked the island, the team was deeply moved by the sight of a boy drawing with pencil and paper on the concrete bleachers at the barangay hall’s basketball court.

Engrossed in their interactions, the team lost track of time. Dusk was turning to nightfall; the last boat had already departed. Stranded a mere ten-minute motorized banca ride from the mainland, they faced a night on the island.

Dasugo, recounting their mad scramble, chuckled: “We started calling for anyone who knew someone who had a boat. Just then, a group of young men arrived, delivering supplies. We mustered our best smiles and asked, ‘Maaari ba kaming makisakay?’—Can we hitch a ride back? Oh, and there’s eight of us, by the way, haha! Thankfully, they agreed, and we all squeezed in for the ride back.”

At the barangay basketball court

Preparing for Singapore

Once the team knew they were shortlisted, they quickly went to work. They were on school break, but the work wasn’t any less intense. John Mark Fabie, JM to friends, recounts: “We worked with our mentor, architect Dasugo, with a board and pen in front of us so that we could suggest and brainstorm. After we decided on one direction, then began the sleepless nights working on the plans and models.

“For the division of labor, we did not go the usual route of equally dividing the labor among the team members. Rather, we recognized each other’s strengths and utilized them for the betterment of the project. Although we always gave suggestions to whatever a team member was doing, we generally divided the work into something like: Raiven, Gianne, Jaimeeh, and Jade did the majority of the model making and concept design; Marvin and Trishia did the majority of the Photoshop work and presentation detail; while I did some model detail, model compilation, and the rendering work; and Anthony did the majority of the planning and detail drawings.”

What’s a third space?

The day before their flight to Singapore, Trishia and Marvin revisited Puro Island, delving deeper into the community’s need for a “third space”—a vital, inclusive communal space distinct from home and school. Marvin shares, “We chatted with the kids, trying to see through their eyes what it’s like growing up here without a space to unwind and express themselves creatively outside school.”

Propitiously, on their way to Puro, Trishia and Marvin shared a boat with a young college student returning home from a week of studying on the mainland. The serendipitous encounter underscored the value of their project, a story they would later recount in their presentation in Singapore.

Fundraising

The biggest obstacle to joining international competitions is often access. Although there was no entry fee for the Student Charrette, covering travel expenses was a huge barrier for the students. With the help of UNP Architecture Dean Fatima Nicetas Rabang Alonzo, the team sent out some 50 letters seeking donations. Despite the valiant effort, the result was disappointing. Trishia recounts:

“We were 90 percent done with our project but needed 90 percent more funds! We bought our plane tickets and booked our accommodations on credit. During this time, many were rooting for us, but inevitably, there were some who questioned the point of going since they didn’t think we would win.”

As their financial prospects seemed bleak, the university president, student council president, and faculty rallied to their aid. But it wasn’t until two gentlemen responded to the solicitation letters and asked to meet with the students and their teacher that the situation turned around. Trishia details:

“Just days before our departure, endless blessings came to us from our University President Erwin F Cadorna; Student Council President Janelle Tenorio; and faculty headed by Fatima Nicetos Rabang Alonso; the local architecture community of Ilocos Sur; and most especially, Honorable Gerry Singson and Honorable Chavit Singson, who extended their support far beyond our greatest expectations!”

Late and lost in Singapore

Buoyed by the many well-wishes and the substantial financial support received at the eleventh hour, Team UNP embarked on their journey to Singapore, filled with excitement. For many, it was their first international trip and flight experience, which added an extra thrill. Despite several hours’ wait at the departure lounge for their late plane, spirits remained high. When they finally arrived, the walk-through of the stunning Changi Airport was an architectural tour in itself, a breathtaking intro to the Garden City.

The original plan was to rest before proceeding to Marina Bay Sands for the orientation. However, due to the delay and various airport distractions, the team had to skip checking into their hostel and head straight to the festival venue. Arriving breathlessly, luggage in tow at 6 PM, they missed it.

Fortunately, Dasugo recognized Paul Finch—“the Festival director who came to visit the GROHE-Kanto WAF practice crits in Manila”—who quickly briefed them on an added challenge for the Student Charrette.

JM Fabie continues the story: “On our way to the hostel, about one hour away from Marina Bay, we got lost. While standing by the street waiting for architect Derick to check the hostel’s location, a kind old lady approached us and helped us navigate the streets. We got to the hostel almost 10 PM, relieved and ready to rest up for the big day ahead.”

The competition

In the WAF Student Charrette, teams are given a design challenge based on a specific theme. Upon arrival at the event, they are informed of an additional requirement that must be integrated into their existing plans. The twist necessitates quick thinking and adaptability, pushing the teams to modify their designs and presentations to incorporate the new element, showcasing their ability to respond creatively and effectively under pressure. The competition mechanics mimic realworld architectural challenges where project requirements can evolve unexpectedly.

The festival’s first two days are spent refining the project in response to the new requirement. On the third day, each team presents their work in live crits with the jury—ten minutes to present and another ten to answer questions.

Trishia Quiming explains how they prepared for the challenge and why they were also extra lucky: “We asked the previous WAF Student Charette Winners from the Philippines (University of San Carlos, WAF 2013) what they experienced during the competition. Luckily, we were presented with a similar design challenge—to feature water in any way, shape, or form in the project. Beyond that, we sharpened our creativity to adapt and face all sorts of design challenges that may be presented to us during the competition.”

Dasugo adds: “I think the fact our team conducted an in-depth site analysis and engaged with the local community was key in preparing us for any additional design challenges.”

Day 1

The team was up bright and early. Before diving into work, they looked around the event space, taking selfies and groufies, of course. Marvin Bayle: “We gathered at our designated work space and brainstormed potential water features to incorporate. We agreed on what we wanted then went about our assigned tasks—CAD models and Photoshop presentations—constantly monitored by our mentor architect, Derrick, as we always get his thoughts on our finished work for comments and suggestions.” As they worked, Royal Pineda and other Philippine delegates dropped by the workstation, offering encouragement and taking photos to capture the moment.

Marvin continues: “We felt incredibly fortunate to represent the Philippines and showcase Philippine architecture. After a long day at the venue, we returned to our hotel to rest and continue working on our design until midnight. During this time, we finalized who would present to the judges. We drafted a presentation flow, ensuring a smooth transition from our initial ideas to the concept and finally to the design solution.”

Day 2

The team arrived at the event around 8 AM, dressed in coordinated jackets, earning them some compliments. Gaining confidence from their prepped appearance and the learnings of their first day, they dove into their tasks with a mix of focus and nervous anticipation, keenly aware of their talented and equally focused competitors.

Post-lunch, the team took the opportunity to attend various crits. Says JM Fabie: “We wanted an idea of what the judges might ask us, what to expect during the presentation, and to have a feel of the presentation room.”

As the day wound down, the organizers presented them with a decision: submit their final PowerPoint presentation by the end of the day or the following morning before 8 AM. Since they stayed rather far from Marina Bay Sands, they chose to extend their day at the venue until 9 PM.

The team returned to their hostel around 10:30 PM. They quickly regrouped to rehearse their final speech and presentation. Their practice session stretched into the early hours, ending only when they felt fully prepared at around 3:00AM. That night was a whirlwind of emotions. JM: “We were excited, we were nervous, we were afraid, and we were happy. After months of preparation and many sleepless nights, our efforts will be showcased tomorrow at the event.”

Day 3

Bayle: “Finally, the day came. We woke up early for the presentation, dressed in barong and Filipiniana with great pride to represent our school and country.” Team UNP arrived at the venue fueled by “a winning mindset, eager to deliver a presentation that would truly touch the hearts of the panel.” After their presentation, the team took the opportunity to interact with the other student delegates, sharing experiences and insights.

The moment of ecstasy

Dasugo: “We were having late lunch at Marina Bay Sands food court. The organizers had said, ‘We will let you know via email if you made it’—if we won. So it was peak hour at the food court, as in, it was full of people, and an email notification popped up on my phone, informing us that we had won and were invited to the gala event. I was so surprised, so happy, sumigaw lang ako sa gitna ng food court!”

The shout reverberated through the crowded space, alarming lunch-goers who thought something terrible had happened.

“People stopped what they were doing and were staring at us. The students were looking at me, and I was shaking, I was shaking, and said, ‘Guys… we won. We WON!! And then they started crying.”

And so Team UNP continued having lunch, their table talk consisting primarily of:

“Oh, my God…”

“OMG, omg, omg…”

“My god, we won…”

Drama before the gala

WAF’s big winners are announced at the gala on the evening of the festival’s last day. Tickets are mighty expensive; only champions get in free. They’re notified hours before to ensure they get on stage to receive the coveted W trophies.

There were eight on Team UNP, including Dasugo. They would have been nine if Jade Gacusan hadn’t had trouble with her passport. But only four seats had been reserved for the winning student team. In a huddle outside the gala hall’s doors, one of the UNP students said, “It’s okay, I don’t have to go inside,” Another said, “Yeah, we’ll go to a café and wait for you there…”

Their teacher refused to let anyone wait outside. He spotted the folks of Student Charrette sponsor Broadway Malyan and pleaded their case. Says Dasugo:

“Kinapalan ko na mukha ko. They agreed, made some calls, and moved things around, so all of us were able to make it in! It was such an emotional rollercoaster!”

Marvin Bayle expressed gratitude for the gesture, noting, “We were very grateful for their generosity. It was wonderful to see different individuals sharing the same passion and receiving well-deserved recognition, especially our fellow Filipino delegates.”

Reflections under starlit skies

The rest of the evening unfolded at the Marina Bay Sands Skypark, where Team UNP, led by Marvin Bayle and Derick Dasugo, soaked in the stunning 360-degree panorama of Singapore. Sipping on refreshing drinks, they relished every moment, aware of a whole new world of opportunities now open to them.

Their quiet reflections were delightfully interrupted when Royal Pineda and several Filipino architects working in Singapore joined them, sparking impassioned discussions about the future of Filipino architecture. “Before we knew it, it was 4 AM!” chuckles Marvin. “Yes, even the Singapore skyline was impressed by our late night discourse! That’s the magic of WAF for you.”

Energized by dreams and the night’s profound realizations, Team UNP left the Skypark wide awake, bright-eyed with hope and optimism, ready to embrace the bright future that awaits.

INTERVIEW WITH TEAM UNP

Why did Team UNP win?

Ponce: We won because each member brought unique skills— communication, creativity, technical knowledge, and teamwork. Everyone brought their own ideas and experiences, which helped us solve problems in new ways. We worked well together and used our strengths to create a unique and impressive solution the judges liked.

Throughout the process, we were happy and enjoyed working together, which definitely contributed to our success.

What criteria did you use to evaluate and refine your concept before submission to WAF?

Quiming: Our project was deeply rooted in sparking positive change in the community. Rather than just aiming to meet competition standards, we prioritized the project’s impact on the betterment of people, especially children. Ultimately, this is what made us stand out. Our intentions are pure, which I believe led to everything else falling into place.

Can you share an example of a last-minute change you made to your design at the WAF and how you managed it?

Bayle: The new design challenge was to incorporate “Water” into our design. Since the island is surrounded by water, we initially struggled with the idea of adding a water feature to our project. Then, we remembered the community’s manual water handpump. During our site visit and interviews, the Barangay Captain informed us this pump was the only water source in the area tested and deemed safe for drinking after the earthquake.

We deliberated to integrate and innovate around this water pump for community use. By distributing tasks strategically, we completed the design on time and ensured that all aspects of the presentation were well-executed.

Dasugo (Instructor): One of the last-minute changes was the presentation itself. We had a polished presentation ready from earlier preparation, but during the charrette, we realized we needed to simplify it and focus more on the core concept and design. We revised the presentation to highlight the design’s key features and impact to ensure that our message would be effectively communicated to the jury within the limited time.

How’d you stay organized and maintain a clear focus under the time constraints and the intense environment, where everybody can watch you while you work?

Ponce: Staying organized and focused was key to the Festival’s live design challenge. Each team member had clear roles and deadlines, helping us manage our time. We also made sure that all resources were available as needed.

Paula: We set goals and milestones to keep everyone aligned and motivated. A collaborative mindset helped us maintain team dynamics. Open communication was vital to quickly sharing concerns and feedback, especially in that fast-paced competition environment.

Ponce: Regular breaks and stress-relief activities kept us fresh and focused, and helped us maintain a positive workspace.

What types of questions did the jurors ask during the Q&A?

Fabie: One important question was the feasibility of the bamboo designs. We answered the question honestly, saying the locals on that island could implement these designs they are already familiar with them, making replicability feasible so long as the locals are willing to participate.

Quiming: One of the jurors wanted to clarify how the project could be materialized, given that we suggested the townspeople could build it. We were having difficulty making them understand the project was inspired by the community’s culture, with “familiarity” as one of our core design approaches. We highlighted that bamboo—used for their houses, sheds, floating rafts, and fishpens—as the main material in the project is an existing and familiar craft in the community. “That’s the answer I’m looking for!” one juror exclaimed, ecstatic with our answer.

How did you practice for the Q&A, and what helped you stay calm and articulate under pressure?

Bayle: Practicing our Q&A session was one of our toughest preparations since we couldn’t predict the questions. Our game plan involved having three members present the project while the rest, along with our mentor, observed and critiqued our flow.

First, we did a run-through before our mentor and team. After the 10-minute presentation, our mentor posed a mix of basic and tricky questions the jury might ask. Each member then took turns responding, to practice giving clear, effective answers.

Those sessions helped us calm our nerves, deepen our familiarity with the project, and fully engage with the design process. By thoroughly understanding our ideas and presentation inside out, we felt more confident and prepared to convey the quality and development of our project during the final presentation.

Dasugo: The Q and A in the WAF crit session was actually very light compared to what we anticipated. Our crit sessions in school were much more specific and pointed compared to those in Singapore. Theirs were more of clarification, not questioning the project itself.

Jade, I’m so sorry you weren’t able to go to Singapore. How did you take it and how did that affect your work on the team?

Gacusan: I couldn’t get my passport due to a record discrepancy at the Philippine Statistics Authority, which takes about six months to correct, while we had less than two months to prepare for Singapore. So, weeks after we got the email that we were shortlisted I realized I wouldn’t be able to go.

I felt all the worst emotions I could ever feel—I cried countless times. But I didn’t let that stop me from helping my teammates, knowing the competition was fast approaching. While preparing here in Vigan, all of us were always present at every session to brainstorm, share ideas, and work on our schematic designs, 3D modeling, and especially conceptualization.

While they were in Singapore, I helped with 3D modelling and the presentation script. We communicated via chat and calls on Messenger. It wasn’t a problem since we’re in the same time zone as Singapore.

What’s the culture and learning environment like at the UNP?

Quiming: Our university’s mission is to produce globally skilled, morally upright professionals with strong cultural values. UNP consistently emphasizes the importance of the cultural treasures that surround us. We used this as the light to guide us in exploring our vicinity.

This led us to the island of Puro in Caoayan, the neighboring town of Vigan City, where our university sits. That ultimately led to the idea of designing an informal learning center that features the tangible culture of the Puro community.

This is a manifestation that the University of Northern Philippines is indeed molding us into architects who carry the burning torch of cultural values to an international scene like the World Architecture Festival.

How has winning impacted your team members personally? How might it impact you professionally?

Ponce: Winning the World Architecture Festival Student Charette Competition has made us feel proud and confident in our architecture skills. It has been a source of motivation for us to do even better. Professionally, it might create new opportunities and showcase our abilities in the architecture industry, opening doors to exciting possibilities ahead.

Can you share a memorable experience or highlight?

Delgado: One of the most memorable moments for me during our preparations was raising funds within our local community, including our professors and local officials, to help us attend the World Architecture Festival. The outpouring of support and enthusiasm from our community, who wanted to see us succeed on the global stage, was truly overwhelming. I remember not having enough funds just days before our flight and asking our relatives to use their credit cards to book my flight!

Paet: Flying to Singapore for the first time is already a highlight. During our participation in the Festival, two moments stood out. First, the jitters and excitement during the actual 15-minute presentation to the jury panel. Second, when they emailed our team as the winner of the Student Charette while we were having lunch. Our team made a scene of utter joy and disbelief, causing other diners to look our way, alarmed by the commotion.

What role did your mentor or professor play throughout the competition, and how did their mentorship influence your project’s success?

Peralta: He provided expert guidance, set clear objectives, and offered strategic direction to ensure our efforts were aligned with our overall goal. This helped us navigate complex problems. His constructive feedback allowed us to continuously improve and refine our project. He also introduced us to valuable resources, which opened doors to additional support and opportunities. His guidance was instrumental, providing the support and guidance needed for us to excel in the competition.

INTERVIEW WITH DERICK DASUGO

How did you balance providing guidance while allowing the students to develop solutions?

Finding the right balance was essential—offering guidance while allowing students the freedom to explore their own solutions. The goal was to foster an environment where they felt empowered to think creatively, while also providing just enough structure to keep them on track with the critical design requirements.

For instance, I had them generate their initial design concepts, which we refined through feedback and iteration. This approach let them fully exercise their creativity, while I stepped in as a mentor to help shape those ideas into a cohesive output that met the competition’s standards.

Can you describe an instance where you intervened or offered critical advice that significantly impacted the project’s direction?

One example was when the team initially proposed a single large building without considering the overall scale. I suggested they design multiple smaller buildings instead, allowing them to spread the program across smaller structures. This approach improved the project’s fit within the context and enhanced the overall massing.

Another instance was in preparing their presentation for the jury. I advised them to focus on key design principles rather than overwhelming it with technical details. They refined their presentation to emphasize familiarity, openness, and climate resilience, which created a more compelling narrative for the jury. What methods did you employ to help the students prepare for the additional design challenge and the live presentation? I used several strategies. First, I guided the students to deeply understand the design problem by studying the competition brief and analyzing site conditions. We conducted a site visit to familiarize them with the context, constraints, and opportunities. This groundwork allowed them to anchor their design, including the additional challenge, in a thoughtful response to the site and program requirements.

How has this competition and the subsequent win influenced your approach to teaching and mentoring?

It’s been significant. This experience reinforced the importance of giving students real-world design challenges that push them to develop creative solutions to complex problems. Competing at the World Architecture Festival provided a transformative opportunity for my students to apply their skills on an international stage.

It also highlighted the value of close mentorship throughout the design process. As a design instructor, I now emphasize facilitating iterative feedback loops, challenging students to critically assess their work, and helping them develop the communication skills to present and defend their ideas effectively.

Finally, our success has motivated me to continue seeking transformative learning experiences for my students.

What are the long-term benefits for the students who participated in the WAF Student Charrette Competition?

Beyond the immediate success of winning, the long-term benefits for my students are profound. Participating in the WAF Student Charrette Competition provided them with a unique learning experience that will significantly impact their academic and professional growth. With graduation approaching, the international recognition of their design skills will give them a strong advantage as they transition into their careers as architects and designers.

Equally important, they developed highly transferable skills—critical thinking, problem-solving, teamwork, and effective communication—that will serve them well in any career path they choose.

On a personal level, I’m confident this experience has instilled in them a deep sense of pride, confidence, and ambition. •