Interview Patrick Kasingsing

Images SHAU (Photography by KIE)

Hello Team SHAU! Congratulations for netting multiple WAF shortlist nods for your already multi-awarded microlibrary! We spoke before about your microlibrary project back in 2018; how has your microlibrary initiative evolved since then?

Florian Heinzelmann and Daliana Suryawinata: Since 2018, we have built a couple more microlibraries. One is the mentioned WAF shortlisted Warak Kayu in Semarang. Since then, we also have built one as part of our public space design, Alun Alun Kejaksan in Cirebon, a 1.2-hectare public space project in the city center. And, finally, we just released our prototype for a prefabricated, modular timber system called Microlibrary MoKa (Modular Kayu).

We also had further requests for other locations where we have the Fibonacci 2.0 on the drawing board, which is a reinterpretation of a previous design that we could not realize and redesigned into a timber version. We are also looking more into the operational and organizational aspects of microlibraries. In our experience, there is a need for both architecture and activation of spaces to work much closer together. Here, the Bima library with Dompet Dhuafa and Warak Kayu with the Arkatama Isvara Foundation and Harvey Center as operators are good examples of how libraries in terms of placemaking should be run.

Your microlibrary initiative is especially notable for addressing information dissemination and environmental impact, two burning issues today. What KPIs did you develop to weigh the initiative’s success? What next after microlibraries, and what conditions will kickstart this next phase?

Basically, the usage of the building—activities and maintenance—are essential factors for its success. Activities we can monitor somewhat via social media, and both, via direct contact with the people who run the library and other stakeholders. For example, we have good experiences in Bandung and Semarang, where an umbrella organization is teaching and supporting a local organization running the library on a day-to-day basis.

Libraries that have a less involved umbrella organization and less communication do not work optimally. As a result, we experienced a suboptimal use of the library in library activities, organizing extra library-related events, and maintenance work. This we have to rectify a bit, and it impacts the future planning of microlibraries, namely, the necessity of having an operator and organizational model selected as early as the design process.

With that, we can react to the context and users early on and the needs of volunteers operating a microlibrary. The next stage is opening up the library idea of being more of a community center. We saw with Bima and Warak Kayu how the space underneath is used for different purposes and how it attracts people. Our next phase is to look into a prefabricated system where we offer the library as a customizable product for individual needs. And hopefully, we can scale the Microlibrary project up and reach a wider group of people in remote areas.

Your work spans differing typologies and scales: from tiny microlibraries to masterplans. How has your experience working on both extremes shaped the studio’s design approach? How has your masterplan experience impacted how you design small projects, like houses, and vice versa?

No matter what scale we work on, there are several design aspects that we always consider. Firstly, designing for a tropical environment under the consideration of climatic aspects. Meaning, from the proper orientation of the buildings where the longer façades face North-South to shading via overhangs, loggias, or balconies, and keeping the East-West façades compact and more closed against solar heat gains.

We also try to have as much cross-ventilation as possible, especially for more affordable projects where air-conditioning is not always a given but still enhance indoor comfort and reduce energy consumption for those who would use air conditioning. Finally, as much as possible, the building plan should be thin, although single-loaded corridors are not always feasible due to efficiency requirements, for instance, in high-rise buildings.

Also, structuring a master plan accordingly to enable airflow via a staggered layout of buildings, taking heights and wind directions into consideration, and implementing sky gardens or porosities in general. Further, we want to integrate more plants into the buildings horizontally and vertically in response to microclimatic aspects. Not only as climatic buffer zones but also for enhancing livability and stormwater management, since Jakarta is prone to flooding.

Secondly, we always think about what the users might enjoy, and we strive to have meaningful and comfortable integrated public spaces. For instance, in one master plan, we designed an elevated circular and wide selasar (covered walkway) that connects all the buildings for pedestrians and cyclists to avoid the usage of cars. This pedestrian “circle line” connects everyone in the compound, from office worker to resident, with all the available amenities and connects downwards at certain points into green and blue, more natural park elements. In that sense, it does not matter which scale we are designing for since the design agenda remains similar: according to SHAU’s socio-climatic principles.

To follow, what do you think is your studio’s greatest asset? To expand, what skillsets or expertise do you wish for the studio to develop further?

We are a relatively small firm, but we can pull above our weight class and take on projects on a larger scale. With our team’s diverse cultural and educational backgrounds, we can add value to a project and approach a design task from different angles. However, having a lean and small organization also has its disadvantages, and we need to be able to scale up, especially to better handle accounting and administrative issues. As architects, we are not educated in such matters, and it quickly could go over one’s head if not handled correctly.

It is also an issue when a firm occupies too much of a niche and becomes typecast. For that reason, we are actively seeking other types of projects. Of course, it is nice to be known for microlibraries, and we love them, but one needs to be careful not to become a one-trick pony.

WAF isn’t your first awards participation; in fact, your studio has made the rounds of major architecture awards and design competitions and won several. What is the impetus for joining competitions? Do you believe that more studios should enter competitions?

The driver for joining all these award competitions is, of course, recognition of the work. But the critical aspect is not only to be recognized as an architecture office, but it also helps tremendously for the sponsor, the community, the city, and the cause. Meaning it creates added value. For instance, Microlibrary Bima and Warak Kayu are the most successful so far and for the latter PT. Kayu Lapis Indonesia, our timber manufacturing company, got tremendous exposure in the Indonesian market through our followers on social media and press coverage through the general and architectural press. It further helps the cause because previous projects’ success and media attention motivate companies to allocate some of their corporate social responsibility or CSR programs to fund more microlibraries. Of course, we cannot guarantee that each and every microlibrary will win an award, but we do our best possible to develop innovative design solutions.

As for whether more studios should join is difficult to answer. Those awards sometimes have a hefty entry fee, and for smaller companies, this can be a challenge where you have to consider your own income and whether you can afford to spend one or two months’ salary of an architect on the entry fee. Luckily, some awards do not cost money and even pay prize money. For instance, the Lafarge-Holcim Award and the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, wherein the latter must be nominated to participate. But in general, international awards competitions are often hiding behind paywalls, making it easier for the wealthy part of the world to participate and showcase their work, whereas the other half is excluded. It would be worth thinking to link entry fees to an average salary of the country where the office has its headquarters, which, of course, needs to be somewhat monitored.

What roles should more design competitions play nowadays, given the world’s present realities? How might they be enhanced?

We assume with design competitions, you mean design awards and not competitions for project commissioning. Regarding the latter, we rarely participate in such competitions because it costs a tremendous amount of time and money for a firm to let a team of architects work on a design competition for project procurement with very little guarantee for success due to the random nature of the juries, especially in an international setting. Mostly larger firms can afford that with a dedicated budget. Moreover, those types of competitions also promote the notion of “design comes for free,” a client attitude we sometimes face in Indonesia and can imagine exists in the Philippines. Sure, one can walk into a bakery and ask for samples and a taste, but you cannot ask for twenty loaves of bread for free with the faint prospect that you might buy from them in the near future for an event that might not happen.

As for design award competitions, we also have concerns, even though we had great success with them. It seems a whole industry has sprung up in recent years, and the number of emails dropping in notifying us of some “early bird” packages or deadline extensions due to “great demand” is staggering. Unfortunately, this might favor the status quo. Therefore, one must be careful or, let’s say, be selective in which award to participate because otherwise, it devaluates an award achievement in the long term due to award inflation. •

Microlibrary Warak Kayu

A multi-programmatic neighborhood icon in Semarang, Indonesia

Written by SHAU

The Microlibrary Warak Kayu is the fifth built project within the Microlibrary series: an initiative to increase reading interest by creating socially-performative, multifunctional community spaces. These spaces are envisioned with environmentally-conscious designs and materials, geared towards serving low-income neighborhoods. Designed by SHAU and prefabricated by PT Kayu Lapis Indonesia, this project is a community, private sector, and government collaboration—a gift from Arkatama Isvara Foundation to the city of Semarang. The microlibrary charges no entry fee and is the home base of Harvey Center, a locally-embedded charity group in Semarang.

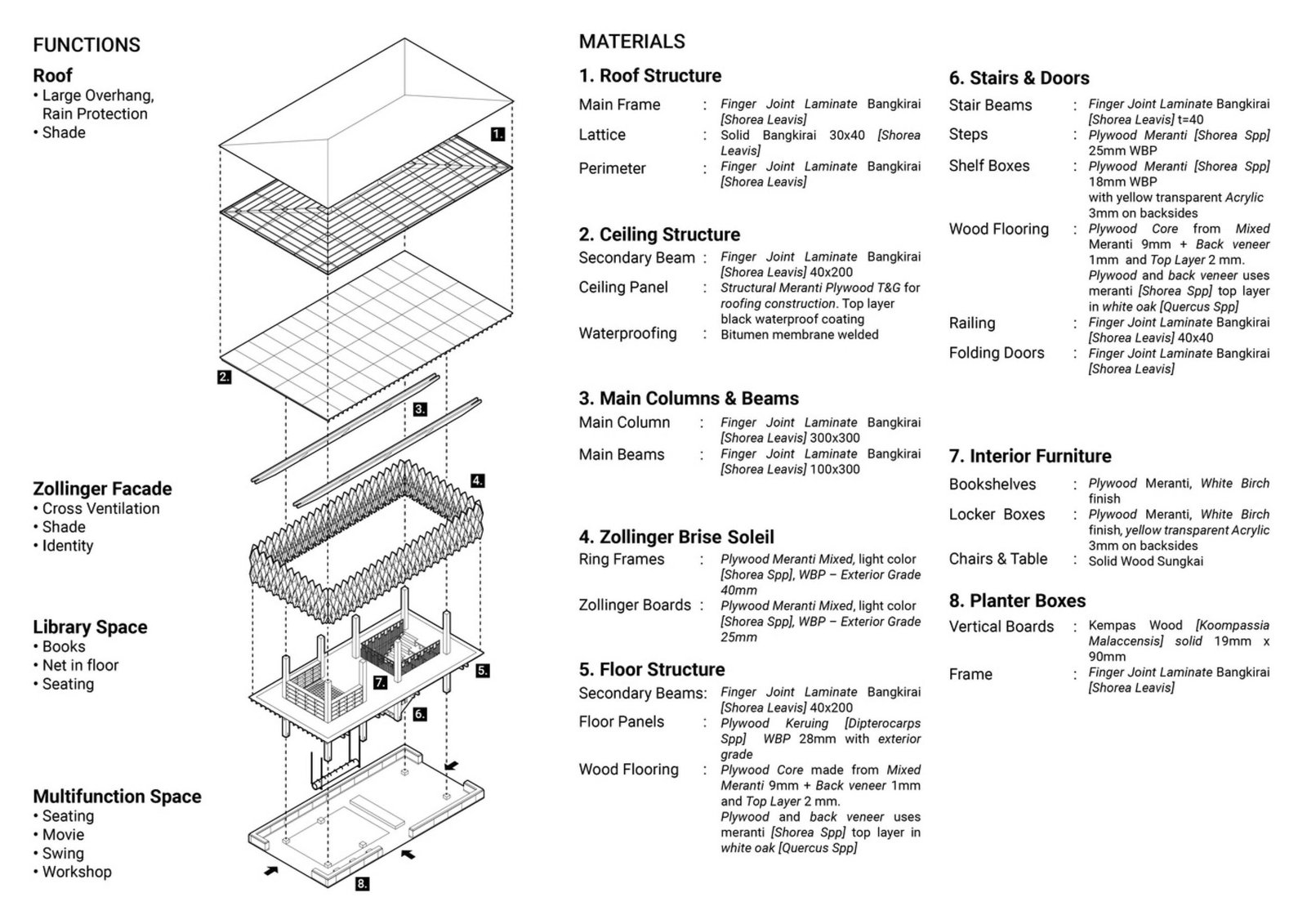

A typological experiment, the microlibrary utilizes a passive climate design with materials geared towards the tropical context. After numerous design iterations, the most favorable design concept was the one with the whole building being elevated, like a traditional rumah panggung (house on stilts). The structure does not only function as a library but adds value by becoming a neighborhood and community center, as well as a living educational spot for wood material and construction techniques. By raising the library, various spatial configurations, multiple programs, and a wide range of activities can be offered.

On the ground is a large semi-outdoor area which can be used for workshops, as well as a wide tribune seating at the entrance for watching presentations or movies. To grab the kids’ attention, we added a wooden swing. The ground area is framed by a ring of planter boxes to create a more intimate atmosphere. Upstairs in the library proper, there is a net where kids can lie down, relax, and read but also directly communicate with parents and friends in the space underneath. It is important to have this multi-programmatic approach of combining a community center with a library, since reading alone is not yet considered a fun activity in the country.

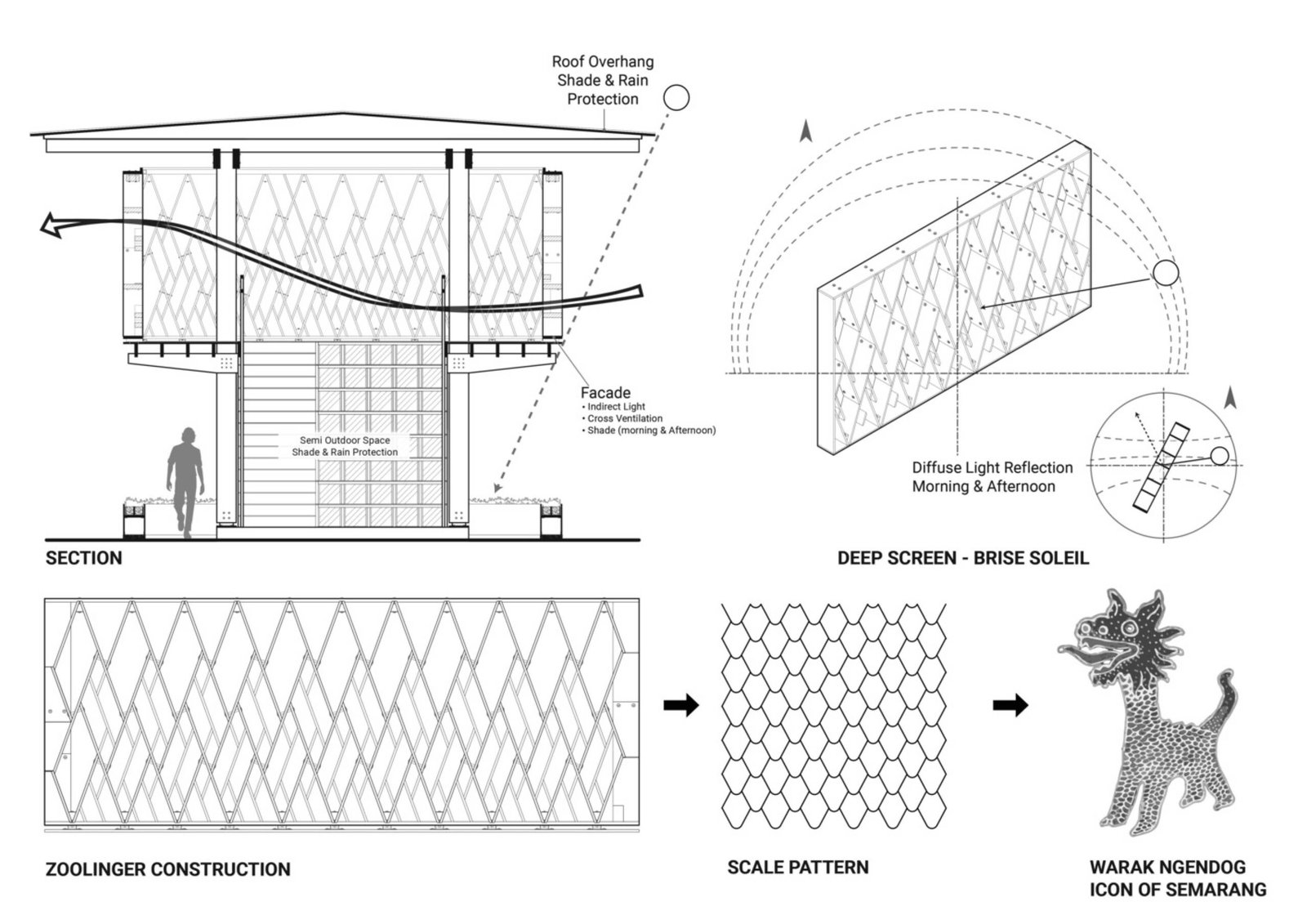

Cross ventilation is an important part of the design; no air conditioning is used. The diffuse-reflected sunlight is designed for reading without artificial lighting, leading to energy savings. The performative, deep brise-soleil façade is inspired by the Zollinger Bauweise—a 1920s German construction system with a distinctive diamond pattern—which happens to also remind us of Semarang’s local mythical creature ‘Warak Ngendog’ and its dragon-like skin. Hence the name Warak kayu in Indonesian, or wooden Warak.

Wood as construction material outperforms many others when it comes to embodied energy, water, air pollution, and carbon footprint; it is also a material that can be regrown. For Microlibrary Warak Kayu, 100% of the wood materials comply with SVLK (Indonesia’s timber legality verification system) and 98% FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) certified. Various types of wood products and wood species were used. For the main structural components like columns and beams, bangkirai-based FJL (Finger Joint Laminate) was used. For decking and the Zollinger brise-soleil, different meranti-based plywood types in various thicknesses were employed. Apart from the concrete foundation, all wooden elements are prefabricated at the factory in Semarang and then transported within 20 km of the site.

Key points: 1. New tropical typology; 2. Social value; 3. Multi-programmatic library & community space; 4. Passive climate design; 5. FSC-certified wood; 6. Multi-stakeholder approach; 7. High-quality craftsmanship within low budget restriction; 8. Small footprint, impactful presence; 9. Local & global.

4 Responses