Interview Patrick Kasingsing

Images RAD+ar (Photographed by William Sutanto)

Selamat hari Antonius dan tim RAD+ar! Hope the team’s doing well despite everything! Congratulations for making it to the WAF with two projects that couldn’t have been more different. But what would say are the qualities these two projects share that make them unmistakably RAD+ar’s?

Antonius Richard Rusli, RAD+ar principal: Hi Kanto.com.ph! The same goes for you guys. Hopefully, everything goes well with you and everyone in the Philippines. Thank you, really appreciate it. RAD+ar’s sole direction in design is to prototype archetypes that fit in tropical developing countries, where much of the world’s population resides, yet where architecture is seen as a privilege that only a few can experience.

Microtropicality is a project that really questions the importance of office spaces in developing countries (where 80 percent of the economy comes from the informal or underground sector) and offers a prototype of a smaller and sustainable office for others to duplicate.

Bioclimatic Pamulang Mosque, on the other hand, is a project that demonstrates the importance of a healthy and sustainable religious space, which 80% of Indonesians visit five times a day.

What roles should more design competitions play nowadays, given the world’s present realities, and how might they be enhanced?

Should design competitions be enhanced? Looking at the vastly different perspectives of the world, we believe that nobody should really pit different projects of varied contexts against each other since nobody can experience them all to really understand their importance and the impact of their existence on society.

If anything, designers should compete in the best avant-garde approach and endeavor to genuinely solve different challenges by locality. More than ever, we have the technology to spread the knowledge and adapt it with local resources.

Your designs highlight the importance of listening to nature and tropical cooling techniques. What do you think tropically responsive architecture such as practiced in Indonesia can teach the rest of the world, especially in the advent of climate change?

Achieving sustainability in the tropics is extremely and unfairly easy—all we need to do is use minimum energy to achieve comfort. We require no insulation to prevent extreme temperatures. Still, sustainability is a must and should no longer be treated as an option.

The act of new construction is at odds with our environmental crisis. Adaptive reuse practices like Lacaton & Vassal show us possible avenues by which to rejuvenate existing structures. However, adaptive reuse is not always possible. If one had to design and build, what should the primary considerations be in light of our climate emergency? You mentioned at a roundtable at this year’s Anthology Festival that “sustainability is a necessity.” How do you express this belief in your practice?

The act of building itself consumes so much energy. And while it is very appealing to aim for net-zero energy taking into account the construction process, it really isn’t practical for people to adapt by themselves. And sure, we are entering an era of adaptive reuse, which looks like common sense, but then again, we must relate these ideas with each project context.

The US and the majority of developed countries in the EU have an oversupply of spaces, so building new buildings there is not only wasteful and unnecessary but also drives up the inflation of property.

This is an entirely different story from most developing countries, mostly near the equator line. Not only is architecture a privilege but, most of the time, decent living spaces are not even an option on the table.

Therefore, sustainability isn’t something to be achieved solely by architects. Such a thought is highly narcissistic. Just look at the numbers. For example, in Indonesia, less than 20 percent of its inhabitants can afford residential space, let alone well-designed and sustainable homes.

Therefore, in our practice, the goal is to make architecture inclusive without reducing our value as architects by making prototypes that can inspire everyday people to be the architect of their own spaces.

To follow, many clients regard sustainability as something that can be added to a building, an additional expense, or a box to tick in a marketing checklist. So how do you educate your clients with regards to ingrained sustainable design solutions from the get-go? Have you said no to clients who clash with you on this point?

As a young practice in a less educated market, sometimes saying “no” is a better option.

Often, in developing countries, sustainable building is seen as both an asset and a liability. Our job is to express the critical need for sustainability to be ingrained and featured as an evocative space from the get-go and help clients get shareholders to share the same perspective.

We in the tropics won the lottery of eternal good weather with plenty of sun exposure. Sustainable and tropical architecture is best done at the design stage. It is much more expensive and difficult to achieve by adding active cooling design features later down the line.

At Anthology, you touched on how social media has helped get “architecture off its high horse” and tempered that statement by saying how the instant access to imagery and data has convinced many that they, too, can be architects. How do your opinions shape how you present RAD+ar in your widely-followed social media channels? What do you want people to get out of what you share? Is there an aspect of your studio or the way your team designs that you think should go ‘viral’?

As we are mere mortals, we find it very narcissistic to say that good practices by architects and engineers are the answer to sustainability in the construction industry. We don’t foresee architects legally being required for all building projects in Indonesia. Not only is it a possibility, but it is also a certainty that the majority of building owners or house owners will be their own architects.

So, we see our role could go two ways: We exclusively practice our professional duty solving actual on-site problems for clients and deliver as much value as we can for their projects; or, we inclusively spread in-depth knowledge about buildings that we’ve designed; to be understood and applied by people at their own pace, which has equal chance to be catastrophically disastrous or create an astronomically positive impact, if adapted the right way.

We do both. Our purpose is to ensure that people can dissect and learn from each project specific to its context, and to inspire. •

Bioclimatic Community Mosque of Pamulang

Written by RAD+ar

Unlike many religious buildings, a mosque serves many more purposes than being a house of worship. Mosques oftentimes also function as community center, school, meeting place, and even recreational space. The Bioclimatic Community Mosque aims to address the fundamental issues of designing a mosque by distancing itself from current architectural discussions based on form and focusing solely on the essence of religious space.

Situated in the middle of a community with a relatively young population, Masjid Darul Ulum Pamulang is designed to be very low maintenance and self-sufficient as the direct heat and high humidity make it an extremely unfriendly environment. Bioclimatic design was an obvious direction to adopt since the site basks in extreme lumen from solar energy 12 hours a day. The use of interlocking concrete roster bricks with openings serve as excellent sun-shading devices that let air circulate. Openings for air inlets and outlets ensure cross-ventilation, while side and top-shaded openings address the stack effect, exhausting hot air above, which is constantly replaced as the air displacement sucks in cool air from below.

To reduce cost and increase efficiency, 95 percent of what was supposed to be brick partitions were replaced with 30,000 pieces of custom roster blocks manufactured by the local community. Apart from letting air through, the roster blocks allow indirect light into the interior spaces yet maintain privacy.

Instead of the quintessential Islamic dome, the Community Mosque of Pamulang has an active green roof to cool down the top-most floors. The green roof also greatly diminishes what would otherwise have been an enormous urban heat island making the surrounding environment warmer than it already is. Such an unconventional decision redefines Islamic spaces based on our postmodern context and needs. Able to accommodate 1,000 people, the mosque is also designed to blend with nature and local culture. As the interior space is actually a shaded outdoor space, the constantly circulating air proved quite beneficial during the COVID-19 pandemic, allowing the community to still gather for worship so long as they observed physical distancing.

Micro Tropicality, RAD+ar HQ

The history of tropical architecture can be traced back as early as the beginning of indigenous societies all across our region. The need for rain to quickly slide down the roof and a high ceiling to keep hot air away from the people in the house led to the stereotype pitched roof and overhangs.

These vernacular pitched forms are celebrated in many tourist areas, but we see them less and less in the cities, as designers and building owners seek to adapt contemporary and international styles in this era of globalization.

Given the environmental and energy crisis we are in today, climatic design, as developed by our forebears over millennia of living in our tropical context, must make a triumphal comeback. With experimentation and research, contemporary architectural expression must adjust and relate to its surroundings to achieve harmony between modern-day architecture and life in the tropics.

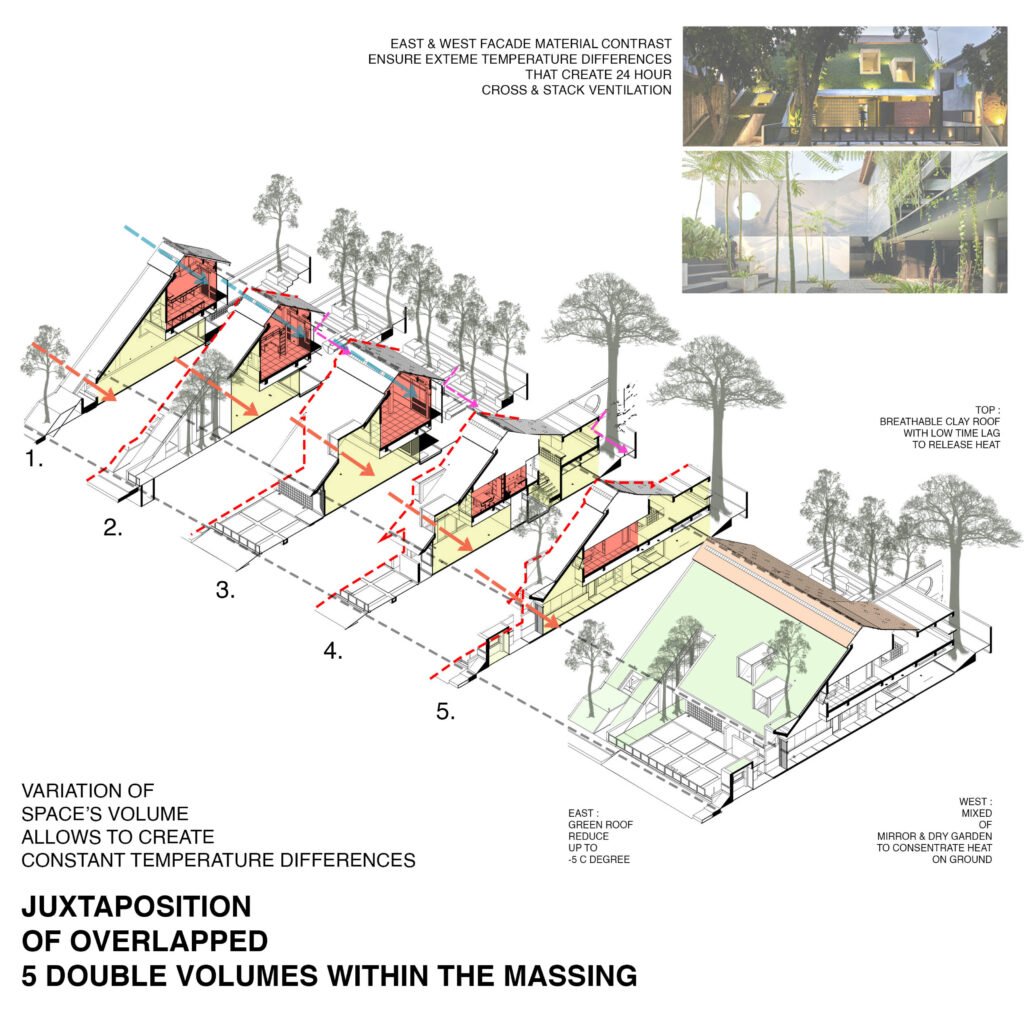

We used the main office of RAD+ar (Research Artistic Design + architecture) as an exploration canvas to see how we can adapt the spirit of vernacular spaces of tropical architecture while experimenting with creating its own microclimate.

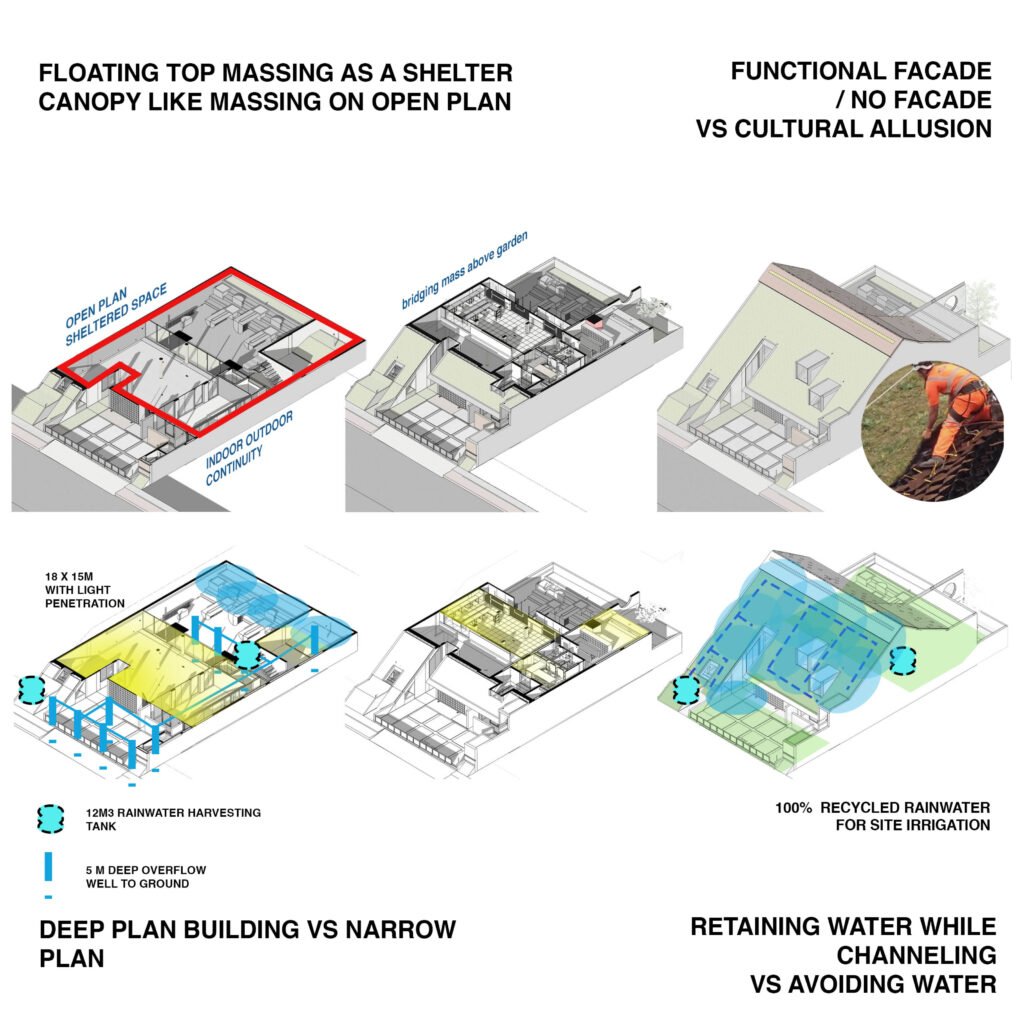

Our aim for “Micro Tropicality” was to design the building to respond to the demands of climate and human experiences. It is much more than just adding an eave to shelter a door or window from sun and rain. We designed an umbrella roof that, at the same time, ventilates and illuminates to make the landscape dense in foliage. The plants would, in turn, invigorate the environment with fresh oxygen. The multilayer façade reduces radiation, directs the breeze inside, shades the windows, keeps the walls cool, and directs views.

We strongly believe that an architecture that recognizes the specificities of tropical latitudes and demonstrates its expressive design guidelines will reinforce the local culture. Such architecture will, in a better way, host people’s experiences, adapt to the spatiality of the place, and recognize the socioeconomic and human conditions. And all these attributes will facilitate their appropriation and recognition.

Our design approach demonstrates a dialogue between architecture and tropical environments that seems to contradict conventional understanding of the tropical architecture approach:

Retaining water while channeling it versus directly channeling and avoiding rainwater

The dramatic angle of pitched roofs in the tropics was necessary for channeling water directly to the ground with excellent efficiency, so the building could endure heavy downpours during the rainy season. But given our cities’ flooding problems and water scarcity, we must think of ways to distribute water load while absorbing as much water as possible and releasing it slowly for later usage. At Micro Tropicality, 100 percent of the rainwater gathered at the site is used for irrigation.

Functional façade / no façade versus cultural allusion

As tropical norms have been integrated into our homes for hundreds of years, most tropical building construction has unwritten guidelines concerning integrating the façade with the roof. At RAD+ar, we always aim to set examples of how functionality can be integrated with aesthetic approaches.

Deep plan building with maximum illumination strategy versus narrow plans

To minimize the use of artificial lighting during productive daytime, most tropical building guidelines recommend a maximum width of 12 meters. Rather than adhere to such limitations, we experiment with puncturing 18-meter-deep plans with vertical openings to maximize natural lighting during the daytime without compromising form and space.

Manipulating internal temperature thru East-West versus North-South orientation

Due to the sun’s extreme heat, most tropical buildings tend to use north-south orientation to maximize illumination and keep direct sunlight on the shorter rather than the longer sides of the building. However, since north-south orientation is not optimal on all lots, we experiment instead with façade surfaces, especially on the east and west sides of the building. In addition, we use the opportunity to create a greater temperature difference within the structure which aids in controlling the building’s own microclimate.

2 Responses