Interview Patrick Kasingsing

Images John Lanbert Rafols and students of the

Architectural Photography class of Greg Mayo

Video John Lanbert Rafols

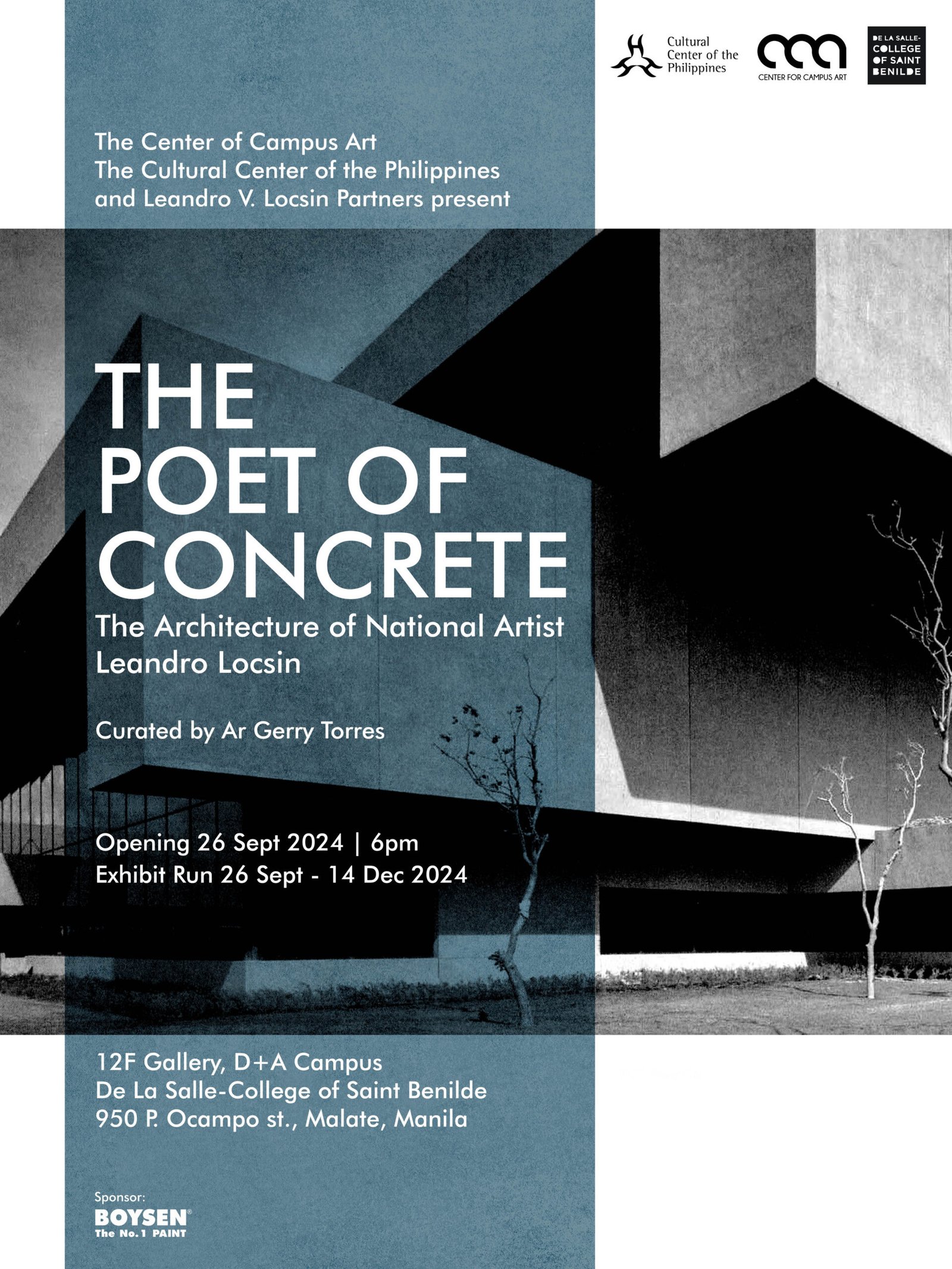

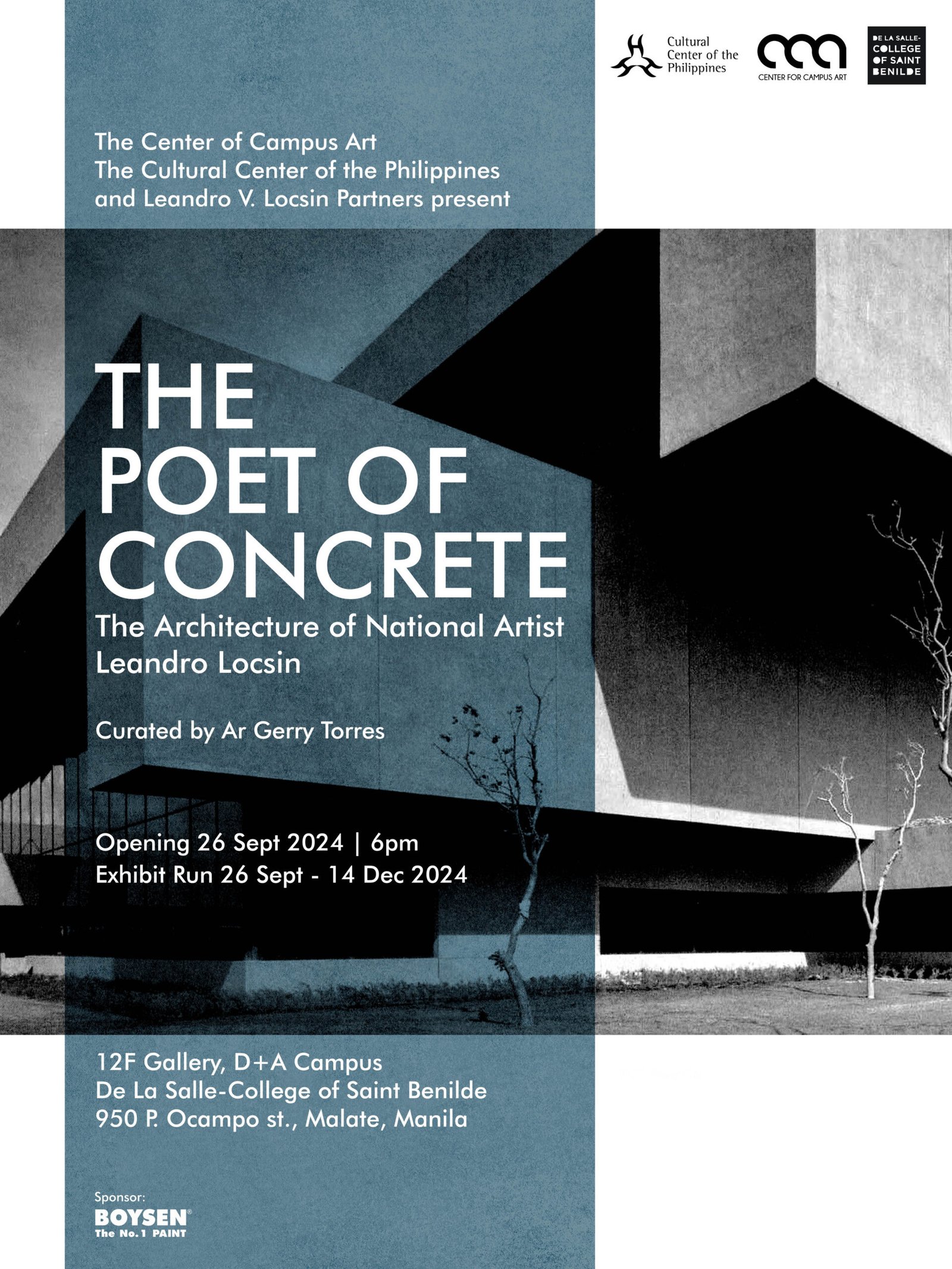

Good day, Gerry! Glad to have you in Kanto! You are presently at work on “Poet of Concrete: The Architecture of Leandro Locsin.” Can you let us in on the story behind the conception of this landmark exhibit? What inspired you to stage a show on National Artist for Architecture Leandro Locsin at this particular time? And please talk a little bit about the title, “The Poet of Concrete,” for the benefit of those who may not be overly familiar with his work.

Gerry Torres, Director, Center for Campus Art: Ever since the Center for Campus Art, the unit I’m heading, began in 2015, I’ve always wanted to feature our National Artists. I felt that those who were chosen for this recognition—the highest given by our government to our creatives and an award which I respect very much due to its stringent selection process—were not known by our students. Benilde has been identified strongly as a design and arts school, so I thought it fitting that our students, teachers, and other members of the academic community should be aware of the award and those who have been honored by it. I’ve curated solo exhibits on six NAs: Ramon Valera for Fashion, Lino Brocka and Ishmael Bernal for Film, Ryan Cayabyab for Music, Cirilo Bautista for Literature, and Abdulmari Imao for Sculpture and Visual Arts. Leandro ‘Lindy’ Locsin will be the seventh.

I grew up with the works of Locsin. His architecture is the one I recognize the most, even as a student of architecture at the University of Santo Tomas. I’ve spent a lot of time at the CCP for various cultural events, watched concerts at the Folk Arts, learned printmaking when the Philippine Association of Printmakers was housed there, and attended many graduation ceremonies at the PICC Plenary Hall as Benilde’s former Dean of the School of Design and Arts. In addition, the lost Locsins—Magnolia House, Greenbelt 1, the old Ayala Museum, the Mandarin, and the Intercon, were spaces that I experienced and enjoyed. I have many fond memories of these buildings and can still picture them in my mind. Locsin resonated with me on so many levels. Plus, we’re both from Negros, so the affinity is strengthened.

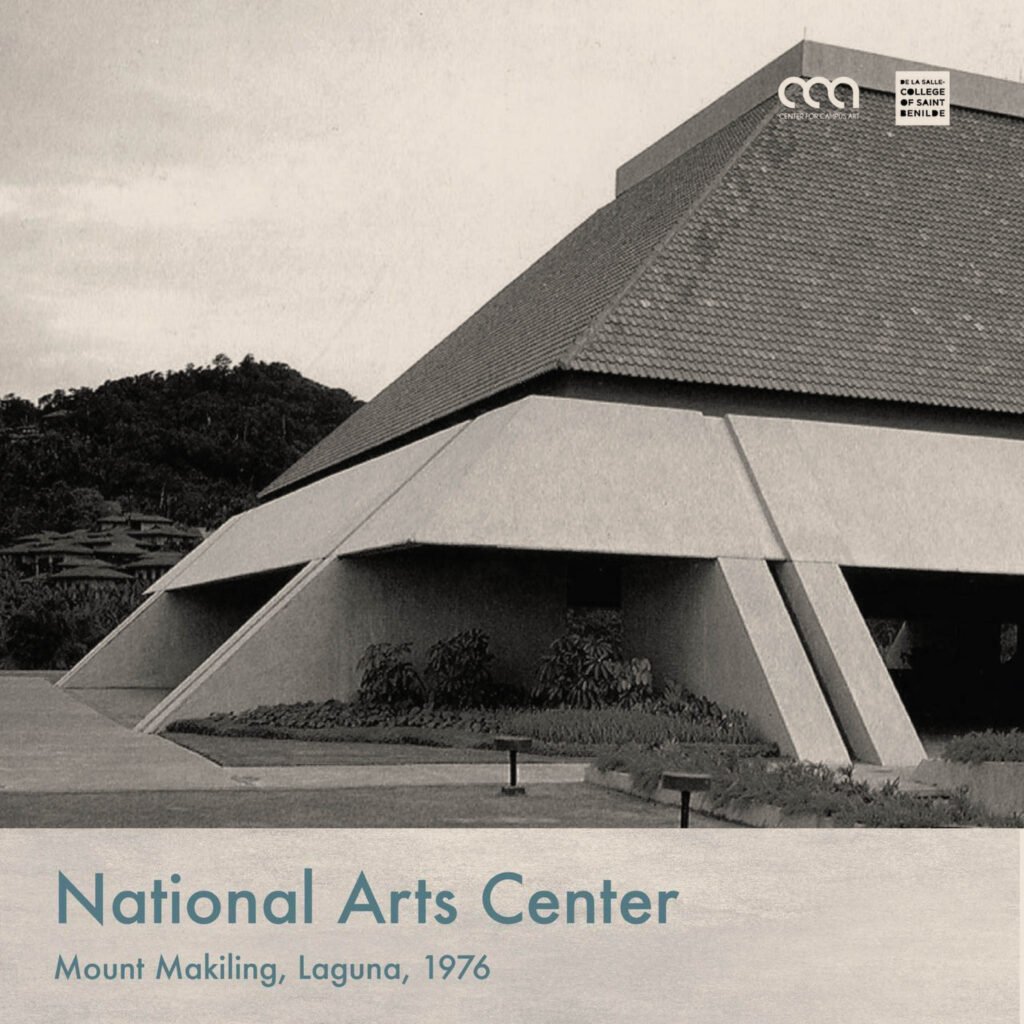

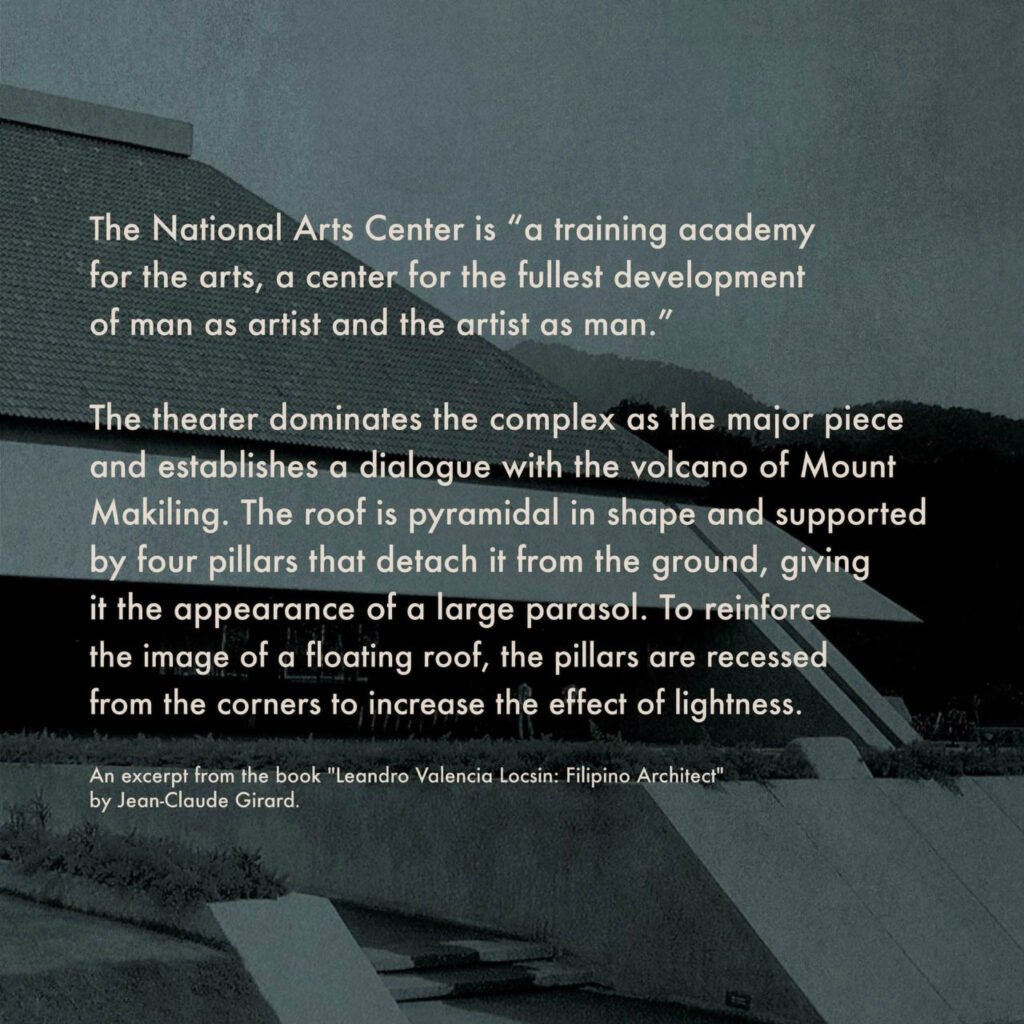

I chose “Poet of Concrete” as the title because Locsin made the material perform in new and surprising ways. He made concrete float and fly, stretch and cantilever as never before, curved and softened it, and altered it in new ways with his numerous chipping and bush hammering techniques, much as how a poet would play with words. He elevated one of the country’s most ubiquitous and, for some, lowly materials into works of art.

We’ve probably encountered Locsin’s work one way or another, especially in Metro Manila, owing to his practice’s prodigious output. Decades on, Locsin is still seen as arguably the country’s most accomplished architectural figure. How has Leandro Locsin and his practice stayed relevant and respected within the Philippines’ architectural realm? What would you say are aspects of his architectural approach that still resonate with contemporary audiences?

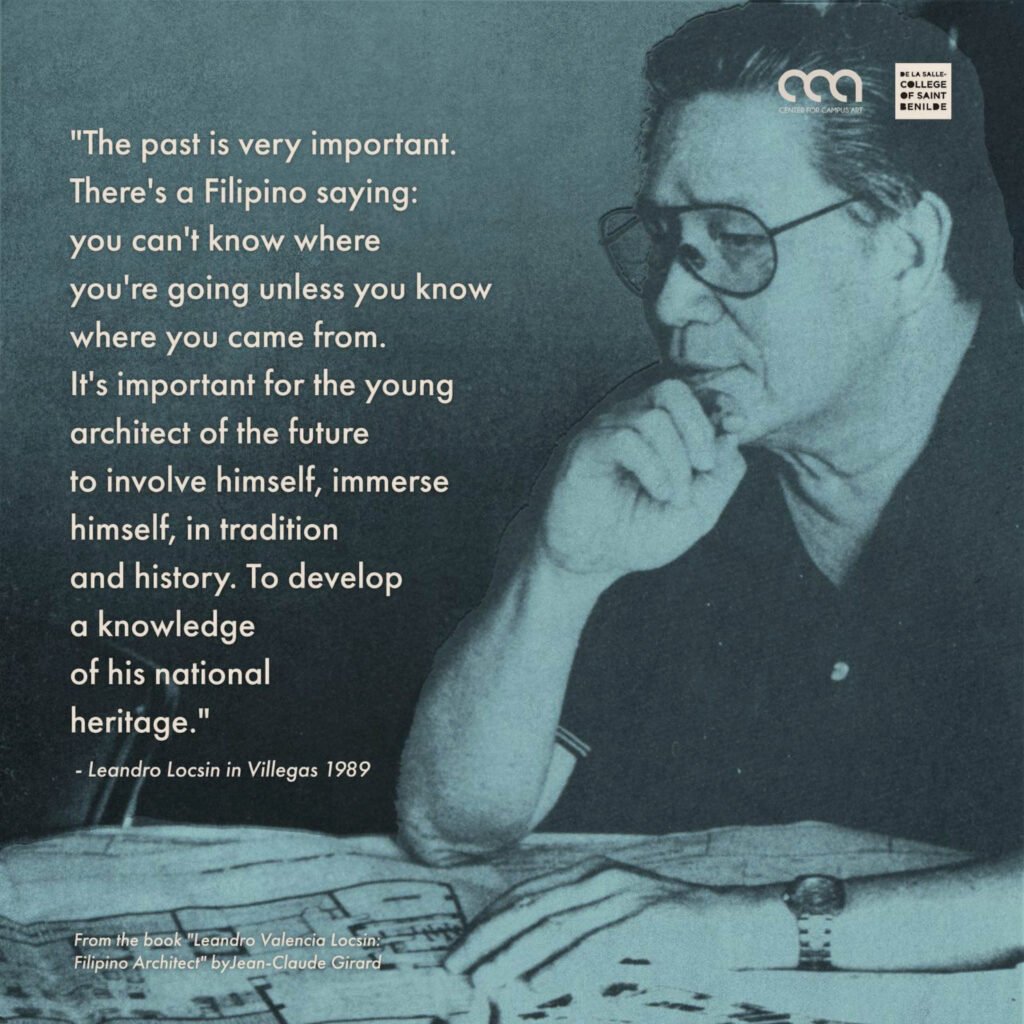

When you ask most Filipinos to name an architect, most will say Leandro Locsin. That was the case before, and I hope it still is. This was most probably because of the number of projects he had, the amount of attention they got, the identifiable elements of his style, and the varied typology, a lot of which were experienced by people first-hand being public buildings that he became widely known in the country. Locsin passed away in 1994 when Philippine-style Postmodernism was just starting to have its grip on our cities, so his work remains an example of bygone architecture—Tropical, Modernist, and Brutalist. His work became potent examples for us to compare with succeeding styles, for better or worse, and plays an important part in our country’s architectural legacy. They should be studied for the lessons they can impart.

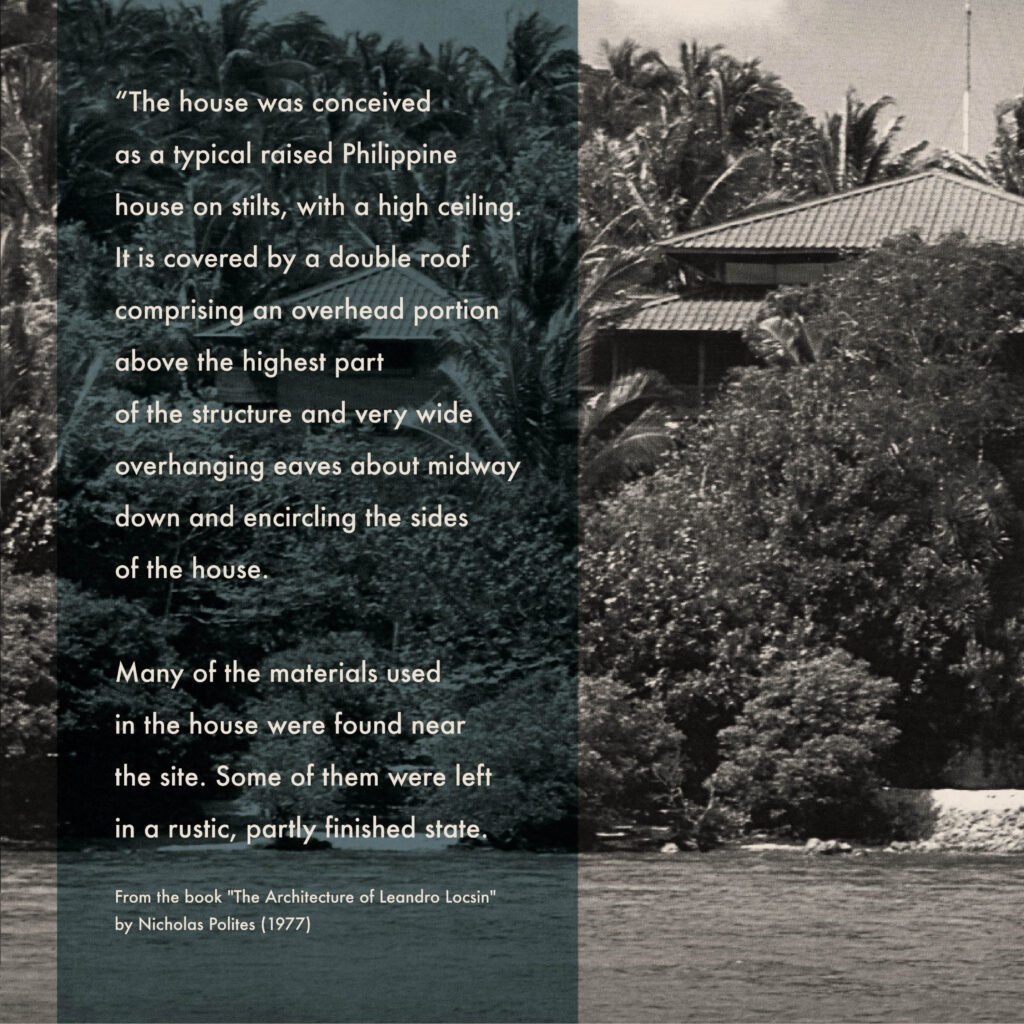

The Big Idea. The plasticity of concrete. Play of spaces, dark to light, low to open. The economy of materials. A sense of restraint. Clean lines. Designing with nature, the house and garden, and views. Working with art and artists. Those are some that I can think of. His use of Philippine materials like hardwood, capiz, and adobe makes me nostalgic for a past when we still had those resources available in quantities large enough for buildings. His ideas can still be adapted today, providing positive qualities for contemporary architecture.

Beyond showcasing Locsin’s architectural achievements, what do you hope attendees will take away from their experience at this exhibition?

To be aware that there was a time when a Filipino architect was able to define and influence Philippine architecture; when our architects and their buildings were recognized and celebrated beyond our shores. When we looked into our own to create distinct, extraordinary structures that celebrate our land and culture. That there was a time when Filipino architects were the stars of the buildings they designed and not the developers or the media personalities.

That architecture is fragile, even if by a National Artist. That their work can disappear virtually overnight. That conservation efforts remain tenuous and, many times, vulnerable to political and economic forces. That the architecture of the past can provide inspiration for architects today. That it helps to have the right clients.

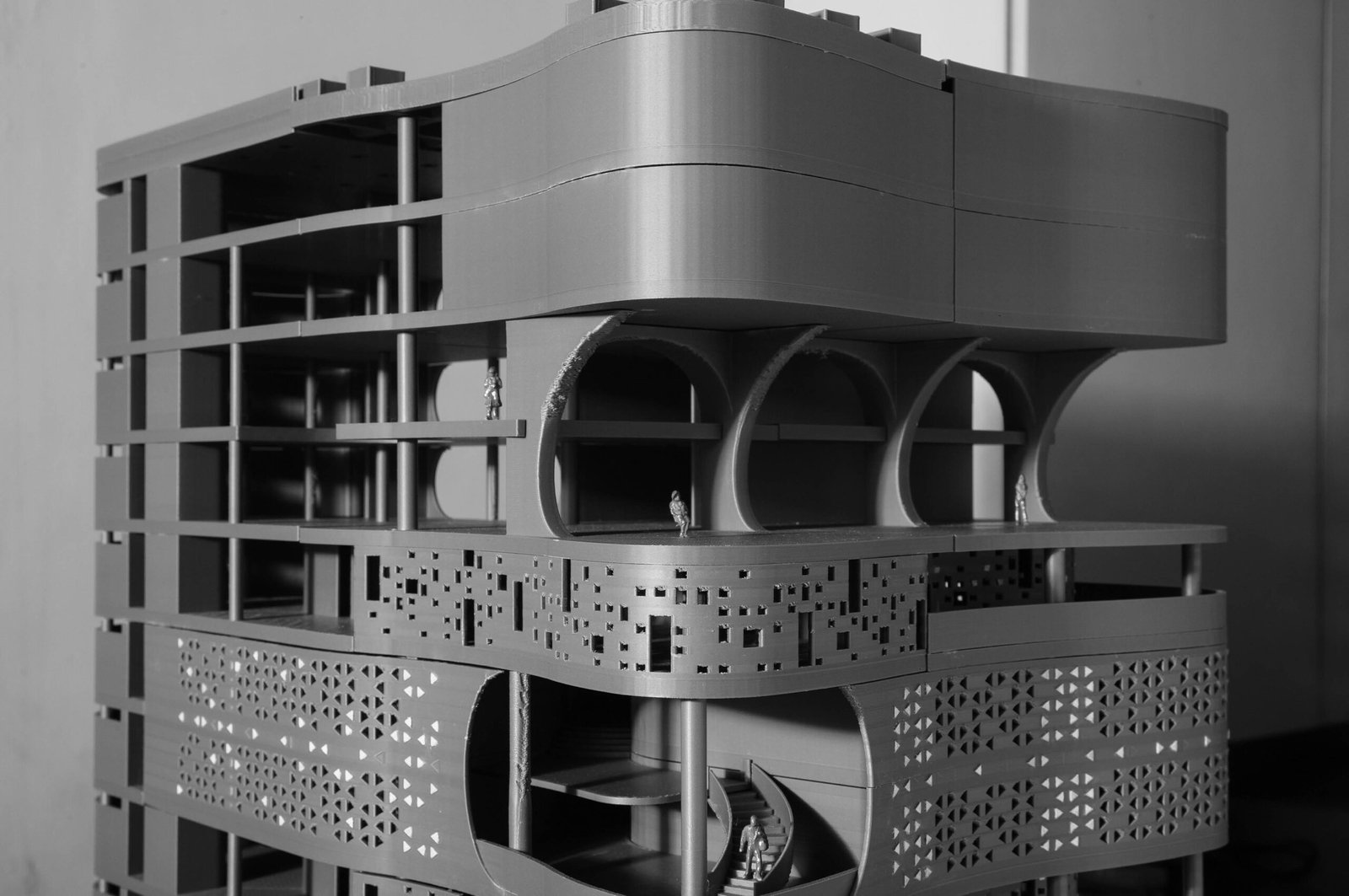

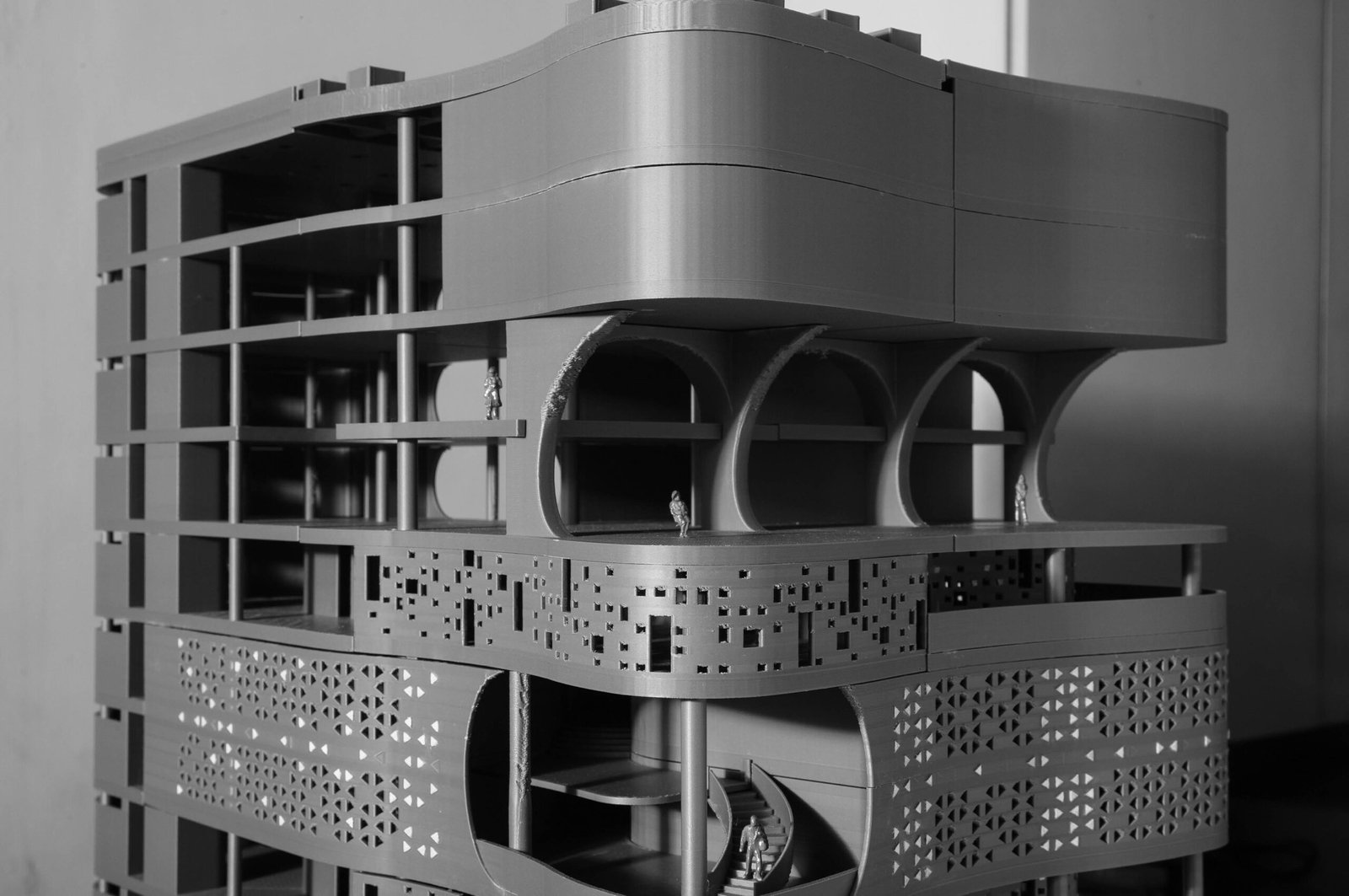

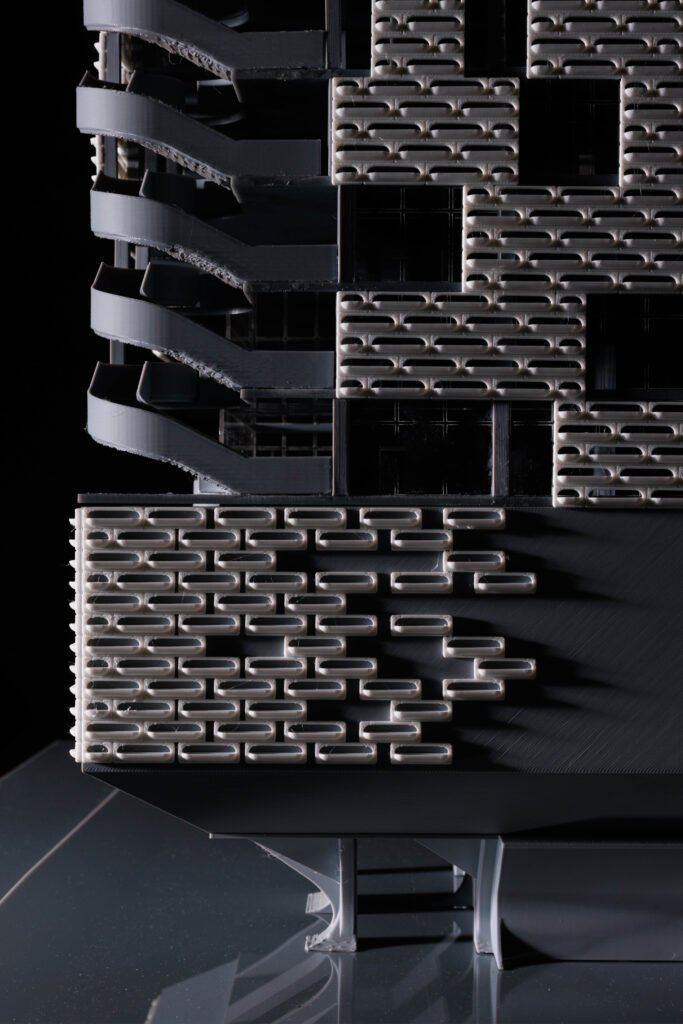

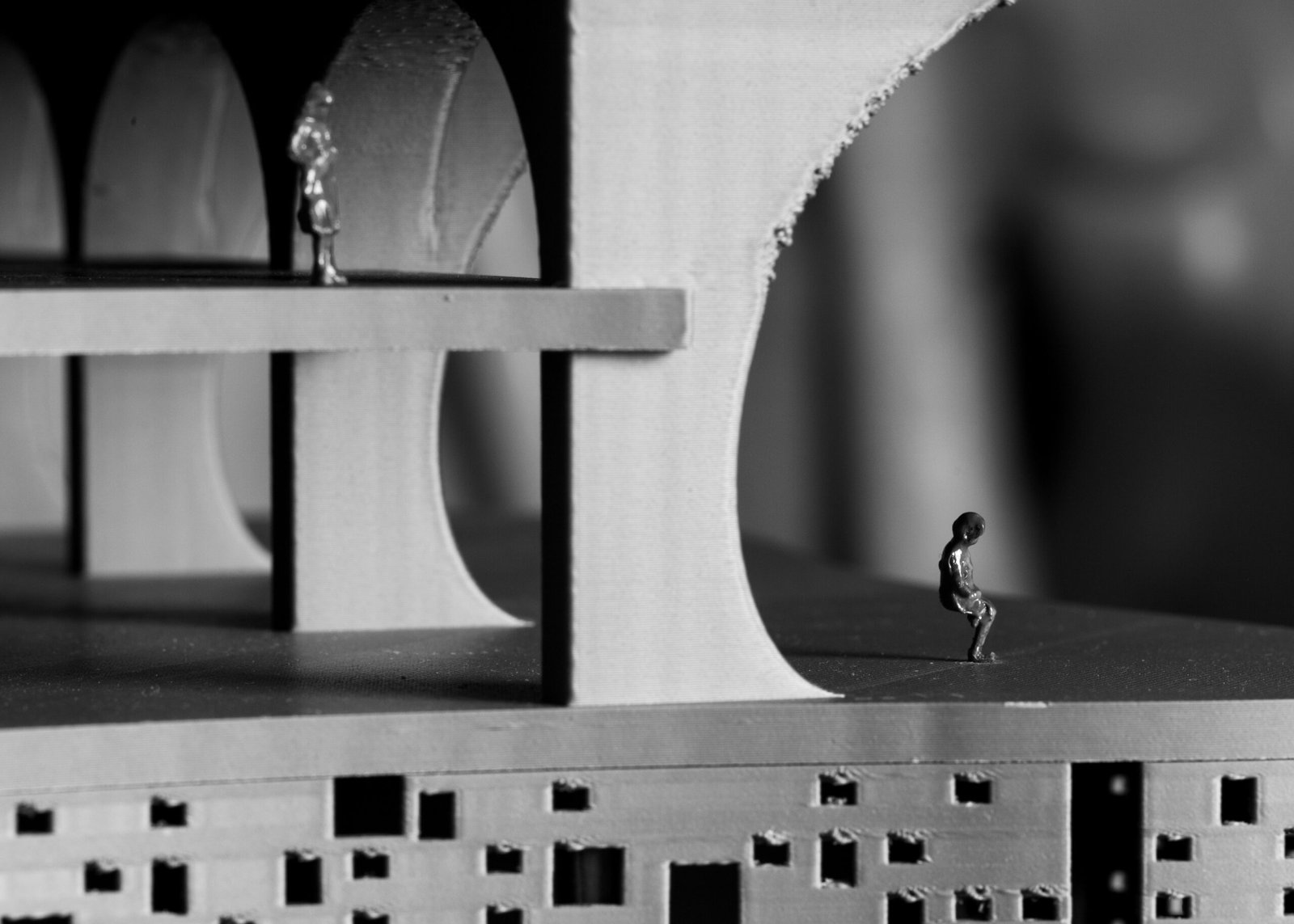

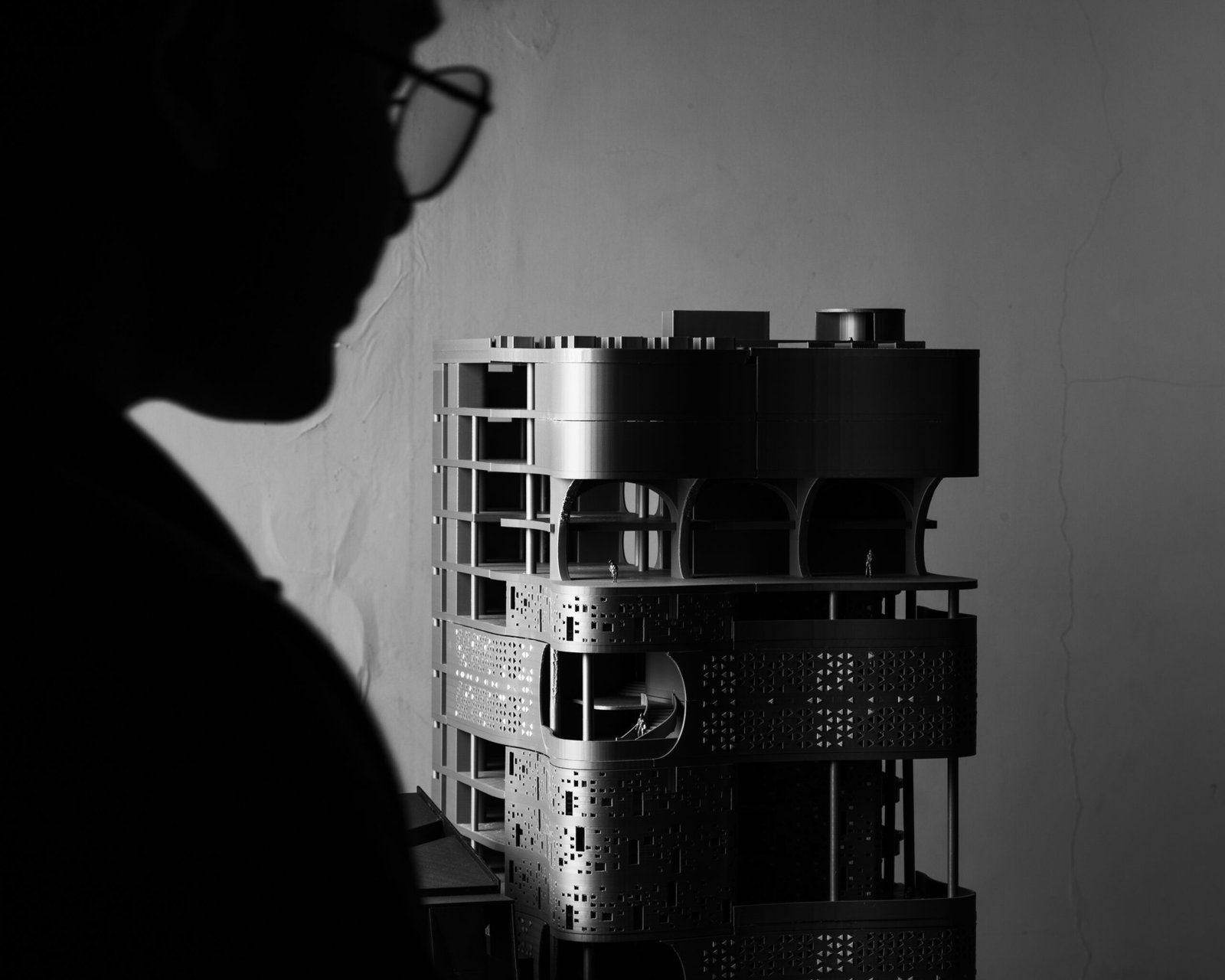

School of Architecture by Jara Bugnot and Anjello Ching, photographed by Hannah Bulayong

School of Architecture by Joshua Rana and Joshua Hermosa, photographed by Andre Jose Leng-Ay

Are there specific works by Locsin or elements within the exhibit that you would recommend we attendees pay particular attention to?

The Philippine Pavilion at the 1970 Expo in Osaka. Even just through plans and photos, the design is audacious in its bravura. I hope a model can be made of it today. This was before his Brutalist phase, so it’s surprisingly different, but it also gives us an idea of how Locsin pivoted his style to what we are now. His evolution is illustrated here.

His last project—I gasped when I saw it—was so different from his iconic works, like he was meditating and looking inwards, yet so fitting for the client. I shall reveal no more.

The hand-drawn drawings! Knowing they were all drawn by hand, they’re amazing in the amount of detail and I can imagine, daunting for the draftsman when faced with the size of the paper. I can only admire the dexterity and patience of the unnamed architects and draftsmen who were drawing them day-in and day-out, but now, the human element makes them look like works of art. It seems unthinkable that they designed like that, pre-CAD and Revit and 3D imaging and modeling, but based on results, which are pretty spectacular, the process was quite effective.

And we have a catalog which we hope to launch together with the Locsin exhibit.

“I chose “Poet of Concrete” as the title because Locsin made the material perform in new and surprising ways. He made concrete float and fly, stretch and cantilever as never before, curved and softened it…much as how a poet would play with words.”

While this is not the first show on Locsin’s oeuvre, yours appears to be one of the more comprehensive efforts in terms of scope and work coverage; How does your exhibition set itself apart from previous shows dedicated to Locsin’s work? What new perspectives or insights does it offer on his architectural legacy?

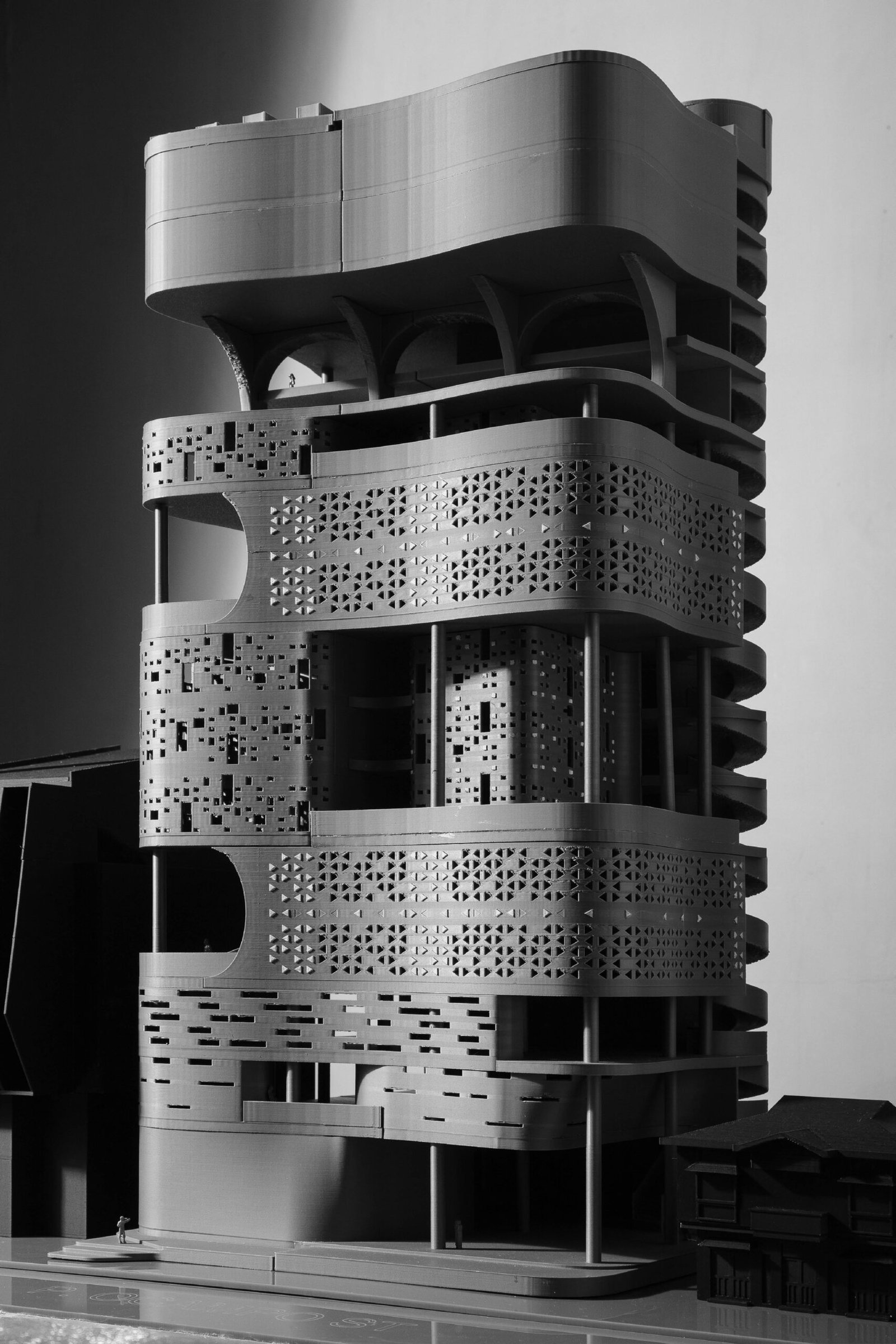

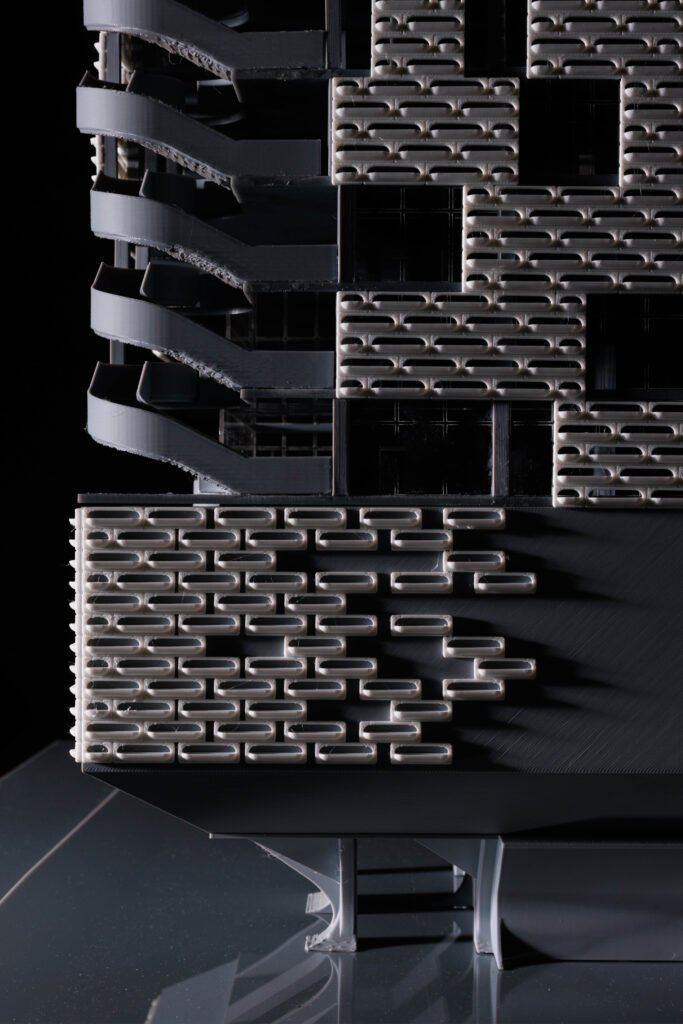

I haven’t been to any of the previous Locsin exhibits, so I can’t really say. But I’ll be bold enough to say that there will be new things to see and learn, more thoughts and insights from people who have known or studied him, more material than I can fit in the gallery! There’s so much material to choose from, which is good for a curator. The show is not just a look at the past but also at what’s happening today via the present Leandro V. Locsin and Partners office and how they employ the legacy of Lindy. Then we peep into the future through the works of our architecture students who were tasked to design buildings inspired by, or reacting against, Brutalism and Locsin’s body of work. One section designed a high-rise school for architecture in an existing site owned by Benilde, and I can say I’m very proud of what they’ve produced.

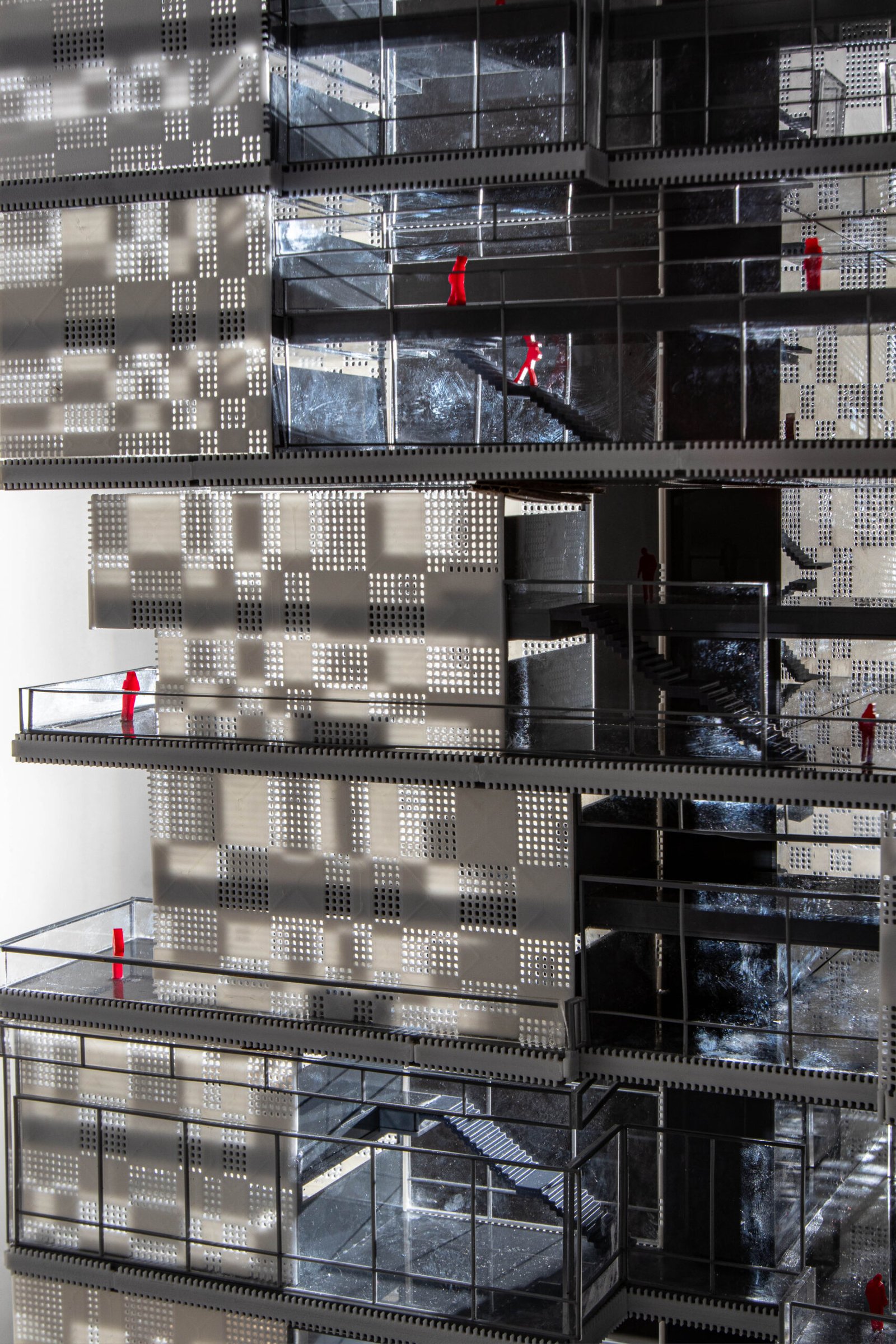

School of Architecture by Kim Nacion and Charles Jenkins, photographed by Matthew Mangulabnan

School of Architecture by Kim Nacion and Charles Jenkins, photographed by Matthew Cole Suguitan

It is regrettable that despite Locsin’s stature and the respect he is accorded in artistic circles, several works of his have met demolition or are in current danger of meeting the wrecking ball. How do you see the role exhibitions like yours play in raising public awareness or influencing preservation efforts?

I’m a history teacher, so a part of me dies for each heritage building that gets torn down. Sometimes, I feel that it’s a losing battle when the preservation of our built heritage is faced against the strong, relentless forces of politics and big business. I hope it will still change. But at the very least, with the available technology, let’s document them before we tear them down so they can be rebuilt even as study models.

We hope to include in the exhibit the current preservation strategies of the CCP Theater of the Performing Arts, now renamed CCP National Theater, so that our students and the public can learn what is being done and how, with today’s technology. A lot of people do not realize that some of our concrete buildings are already considered heritage, so when we highlight the preservation of Locsin’s work, we begin to develop awareness about the importance of our mid-century structures.

I wish your team the best of luck on the exhibit, and I can’t wait to see what you have in store for us. But before we let you go, to close: What lessons do you think future architects can still learn from Locsin’s approach to architecture? What principles or values from his work do you feel are worth emulating or adapting for today’s architectural challenges?

Locsin’s work has been called Tropical Modernism. Therein lies a reminder for our young architects—that we are in a tropical archipelago and that the considerations for such remain constant. Work with the land. Be attuned to the climate and the changes that are happening and will happen. The consequences are real. Use the elements to enhance your architecture. Incorporate art with design and not as an afterthought from the onset. Like Locsin, learn from the past as much as you look to the future. He was able to translate our history and culture into an architecture that looked ahead yet was grounded in what it is to be Filipino and his works eventually became classics of Philippine architecture. •

The Poet of Concrete: The Architecture of Leandro Locsin opens on September 26, 2024 and will run until December 14, 2024. It is open to the public 6 days a week, M-F 10am-9pm and on Saturdays, 10am-5pm, at the 12F Gallery of the Design and Arts Campus of the De La Salle-College of Saint Benilde, 950 P Ocampo St., Malate, Manila. Corollary activities will be scheduled during the exhibit’s run, such as talks and a possible book and catalog launch. Please follow us on Facebook at Center for Campus Art and on our Instagram @benilde.campusart for more details.

About the curator: Gerry Torres is the Principal Architect at Gerry Torres Architectural Design, a firm established in 2000, known for its diverse projects in residential, academic, and museum architecture. He is also the Director and Curator of the Center for Campus Art (CCA) at De La Salle-College of Saint Benilde, where he curates exhibitions that intersect art, design, history, and culture, with active involvement from Benildean students. Torres has curated seven solo exhibitions for National Artists, including Ramon Valera (Fashion), Lino Brocka and Ishmael Bernal (Film), Cirilo Bautista (Literature), Ryan Cayabyab (Music), Abdulmari Imao (Sculpture and Visual Arts), and Leandro Locsin (Architecture).

As former Dean of the School of Design and Arts (2004-2010), he launched four degree programs in Architecture, Photography, Animation, and Digital Film. He also served as the Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Manila (2011-2012) and was the Charter President of the UAAP Manila-Taft Chapter (2021-2022). Torres holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Architecture from the University of Santo Tomas, a Graduate Diploma in Interior Design from Queensland University of Technology (QUT), and a Master’s Degree in Design and Art Education from the University of New South Wales (UNSW). In Sydney, he taught at UNSW and the KvB Institute of Technology.

He has edited two books, “Art Archive 03” (2020) and “Seats of Distinction: Chairs, Collectors, and Captains of Industry” (2024). He has also presented at international conferences, including the Connected 2007 International Conference on Design Education in Sydney, the 17th Annual UMAC Conference in Finland (2017), the Universeum Annual Conference in Brno, Czech Republic (2019), and the ICOM-UMAC Conference in Tokyo (2019). In September 2024, Torres will become the Director of the forthcoming Benilde Fashion Museum.