Interview Patrick Kasingsing

Images The Architecture Drawing Prize (Gareth Gardner)

Good morning, Mr. Shuttleworth, Eldry! Thanks for making time for Kanto today! Let’s kick off our little roundtable with the basics. Mr. Shuttleworth, let’s talk beginnings. Was there a pivotal moment or, perhaps, a moment of inspiration that led to the creation of the Architecture Drawing Prize? How has its vision evolved since its inception?

Ken Shuttleworth, Founder of Make Architects and The Architecture Drawing Prize (TADP): The starting point was the idea of trying to encourage people to continue to draw, you know, in the age of computers and digital information. A lot of students coming out of university in architecture don’t draw. It’s all done on computers now. So, I was really keen to keep the act of hand-drawing alive.

And I think that’s where it started from. But having said that, the computer drawings are also fantastic. So, the idea was to try to have a combination of hand and computer drawings and a sort of hybrid between the two, which people mix and match.

For me, drawing is the most important thing about architecture. Architects actually think by drawing. We communicate through drawing. We think through ideas and work through, you know, the way projects go together through drawings. Drawing is absolutely critical to architecture, and its evolution, from hand to digital, also affects the type of buildings we put up today.

Right. You are an illustrious architect with a lengthy stay as a partner at Foster + Partners, helming the designs of some of their iconic works (London’s City Hall and St. Mary Axe Building, and the Chep Lap Kok Airport in Hong Kong, among others) before striking it out on your own with Make Architects in 2004. Has your personal experience and architectural practice influenced the Architecture Drawing Prize criteria and categories, or how it is generally set up?

Shuttleworth: Drawing is a fundamental part of the architectural design process. It doesn’t have to be a brilliant drawing; if you can get your thoughts across, that scribble on paper will have done its job. So, for me, the idea that you can’t draw, you shouldn’t draw is not right. So, in the realm of architecture, drawing is a language. But it is also an art; it is via drawing that we communicate our spatial visions, whether grounded in reality or unencumbered by it. The Architecture Drawing Prize, you could say, is a celebration of this dual nature of drawing in the profession, a reminder of the power of drawing to communicate and inspire. Naturally, like all things on this planet, evolution is a given. That is why the way the Prize is set up acknowledges the evolution of drawing in the last 50 years, from the days of the drawing board to computers or touchscreens. That’s that!

Okay, you’ve brought up the evolution of drawing and how the prize was set up to recognize the different mediums that facilitate it. Let’s home in on hand-drawing. What do you believe is its enduring significance? And how do you envision the prize, aside from recognizing exemplary works of hand drawing, contribute to preserving the tradition?

Shuttleworth: I think, at the end of the day, we aren’t just celebrating or recognizing beautiful drawings. It’s also about recognizing beautiful thoughts, ideas, and visions. As an architect, I think by drawing, by sketching…I just think visually. And that thinking process is what actually comes out through my sketches and then through drawings.

For me, it’s also about keeping the magic of hand-drawing alive. It’s about, you know, not just going straight to some sort of digital experience and taking time to embrace the creativity, tactility, and physicality of drawing. It still amazes me how something that comes out of your head makes its way through your arms and fingers to finally find translation and realization on a piece of paper. For me and my generation of architects, this was the way we communicated.

Right, so I guess what the prize really recognizes is the ability to tell compelling architectural narratives as executed by hand, digital, or hybrid means.

Shuttleworth: Yes. I mean, as architects, we tell stories and clarify dreams; these are foundational to the concept of our craft. You’re trying to improve people’s lives through built space. That is why it is vital for architects to communicate the vision and mission of a space clearly as they can impact the livability of their creations.

So, for me, I think it’s important that all this communication is still done through hand-drawing. It’s about gaining that tactile connection with a would-be creation. Our experience of built space is physical and tactile, after all. You know, if you go into a room full of drawings, sketches, models, and things, you’re immersed in a spatial experience you don’t get just on the screen.

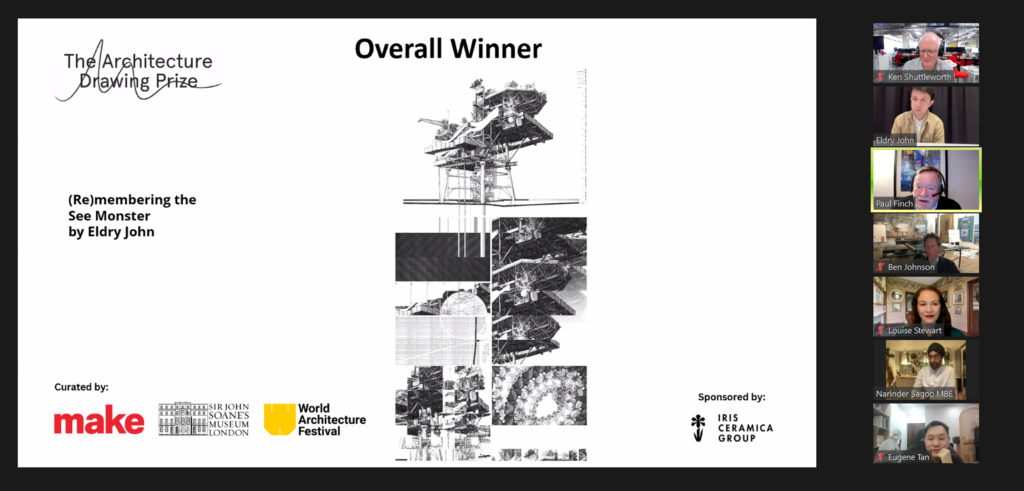

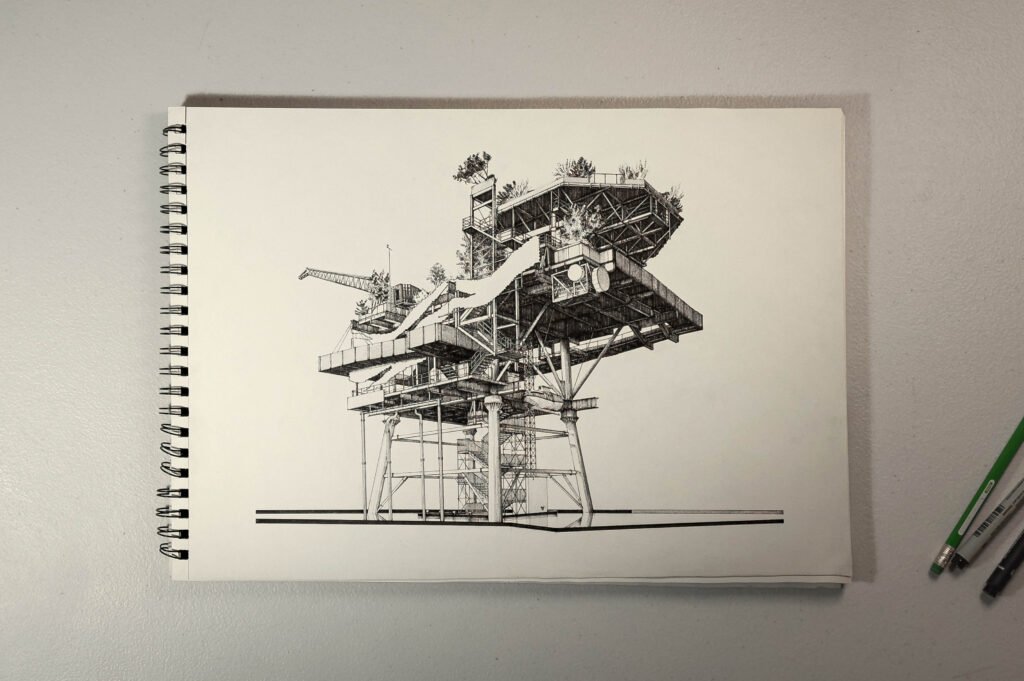

Let’s cede the stage to our newly minted winner, Eldry Infante. Eldry is a good friend, and I have long known his immense talent for traditional illustration. This year, however, I was a bit surprised when he revealed his decision to enter the hybrid category of the Architecture Drawing Prize. On his first try at the Prize in 2021, he was shortlisted under the hand-drawn category. So, Eldry, do chime in and let us in on your decision to enter a new category this year, which seemed to be a fortuitous choice, too! Was this on a whim, or did you really set out to try something different for your second stab at the Architecture Drawing Prize?

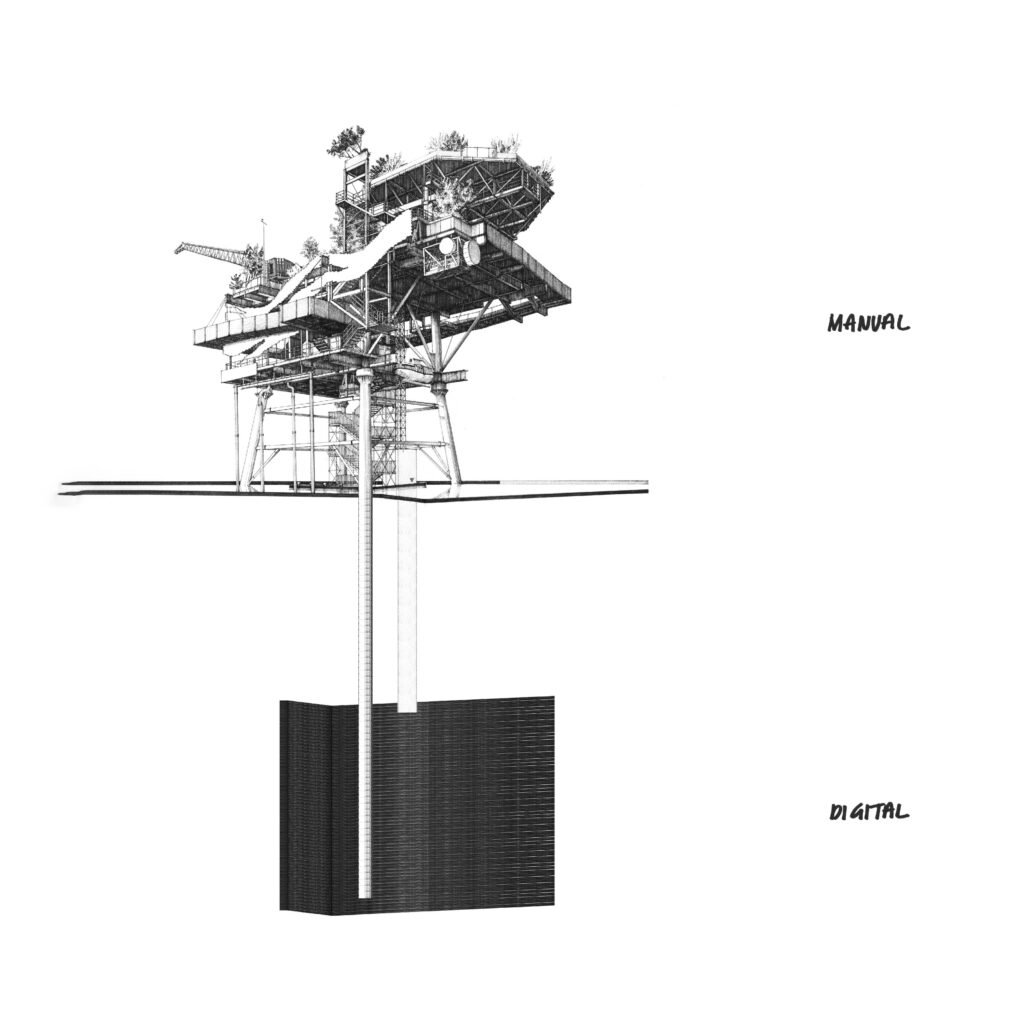

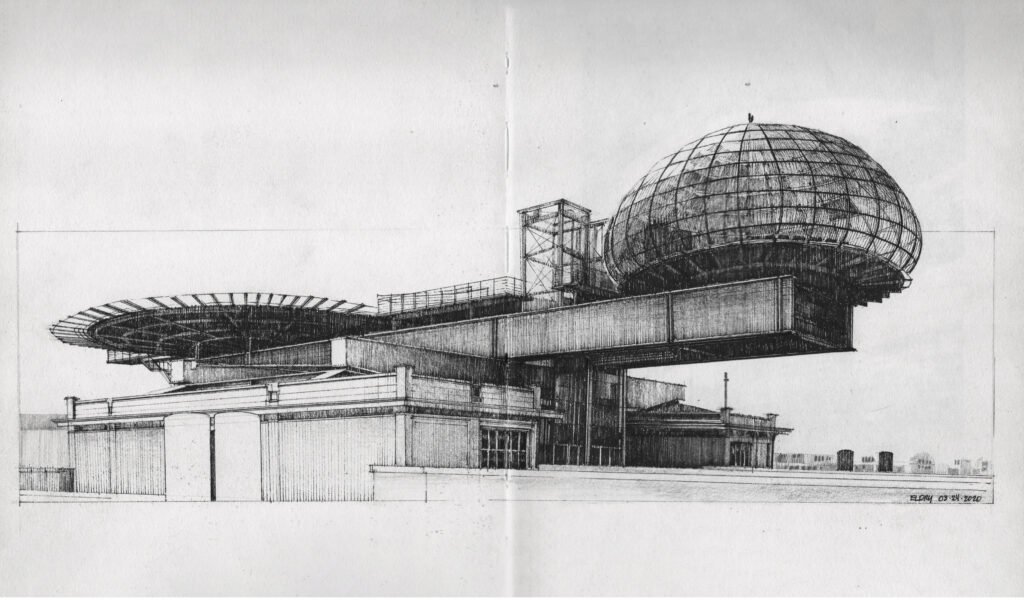

Eldry Infante, Architecture Drawing Prize Overall and Hybrid Winner, 2023: Hello there! I really did want to try something new. I actually wasn’t particular about the category to enter, but I was certain I wasn’t going to do a fully digital one as it was not my forte. So, I considered either the hand-drawn or hybrid categories.

The resulting artwork is also exploratory, as I was trying to discern directions to expand my personal portfolio. In short, it was not made for the Architecture Drawing Prize initially. (Re)membering the See Monster reflects my current illustration direction: faithful hand-drawn renderings of existing structures, but also provides a glimpse into my explorations in drawing, as can be seen with the digital intervention. Rendering the subject matter in my traditional way was already ripe with challenges as it is, but it also pushed me to try something a little different from the usual. The See Monster installation in real life was already rife with metaphor and tongue-in-cheek; my digital deconstruction of it in my illustration adds another layer and depth to the environmental narrative being communicated. The Prize has motivated me to go beyond just drawing and rendering, but into drawing and thinking.

Shuttleworth: But also, I think you’re using the computer as a tool, aren’t you? I mean, the way a pencil is a tool, so is a computer. And the idea that in this day and age, we can actually bring the two together, I think, is quite interesting. So, we’re not saying you must draw by hand. I think we’re saying it’s great to draw by computer as well. But I think you’ve just got to recognize that there are two or three different ways of doing this, and they are all valid. I think your drawing in particular imparts this message well.

Fantastic. As mentioned earlier in our conversation, the Architectural Drawing Prize is as much about rewarding compelling spatial narratives as it is about beautiful illustrations, right? So, how does the jury weigh in on who gets the prize? Do both narrative and craft weigh equally in the scoring?

Shuttleworth: The narrative is important, but often, you know, some of the written passages we’ve encountered are more word salad than story, with highfalutin words just thrown in together with the hopes to impress. So, I think the narrative has to be simple but compelling. There is no need to write a load of flowery stuff about something you’ve just made up. This is the Architecture Drawing Prize, after all, so your drawing must be the primary conduit of your narrative. At the end of the day, however, as much as the narrative is vital to the substance and spirit of the drawing, what we jurors look at is the visual content of the drawing, and how what we see appeals to or evokes an emotional response is probably more important.

Okay, speaking of narratives, Eldry, let’s return to your winning entry, (Re)membering the See Monster. I was able to see the original iteration of the hand-drawn sketch before the digital intervention. Did the narrative make itself known as you debated what to do with the original hand-drawn sketch? What did you want the drawing to do for you beyond being another addition to your illustration portfolio?

Infante: The narrative came much, much later, and I think it helped that I came upon the story in an organic manner, too! It made me appreciate the drawing more, in that while it spurred growth in me, it itself is evolving. I did the initial hand-drawn piece at a time when I felt I was getting stagnant with my illustrations. I drew markedly less because of work, so the piece allowed me to dust off my drawing skills. I liked that my chosen subject is intricate and complex in structure. It allowed me to try my hand at a more complicated subject than usual, as well as to test my patience and refine my line work. The whole experience also proved meditative for my mental health, as it provided me with a much-needed breather from all the work. When you draw, you are focused on a single act and moment where everything that surrounds you melts into the background. It’s just you and your subject.

So, how did See Monster make the jump from meditative sketch practice into Architecture Drawing Prize finalist, and now, winner?

Infante: The first time I was shortlisted in 2021, I just really wanted to be a finalist. I just submitted it without expectations, as this was my test run. When I looked at my finished drawing of the See Monster, however, I thought this could have a fighting chance again at the shortlist. So, I simmered on my work a bit longer than usual and decided to integrate a digital aspect to enrich its narrative, so I joined it under the hybrid category. I had some difficulty transitioning the drawing into a hybrid piece initially; I was constricted by the manual drawing, which I had no intention of expanding digitally.

How was it joining the second time around? How was the experience different or similar when you first joined the Architecture Drawing Prize for The Bubble?

Infante: I have not created any of my drawings for a specific prize; I just picked a piece I thought had a fighting chance and joined. I admittedly had little background and did little research on the prize on my first try. The second time around, while my piece was again not meant for a competition, I was more purposeful about my intent and narrative surrounding the piece. I formed my work’s narrative organically as I researched more about my subject and allowed its story to inspire my digital interventions, arriving at a technique I want to explore further for future works.

Thank you, Eldry! Now, Mr. Shuttleworth, the Architecture Drawing Prize has been around since 2016; I’m curious. Has there been a specific entry, winner, or moment that has stood out for you, and whether said entry or moment has had a bearing on how the Architecture Drawing Prize is set up today?

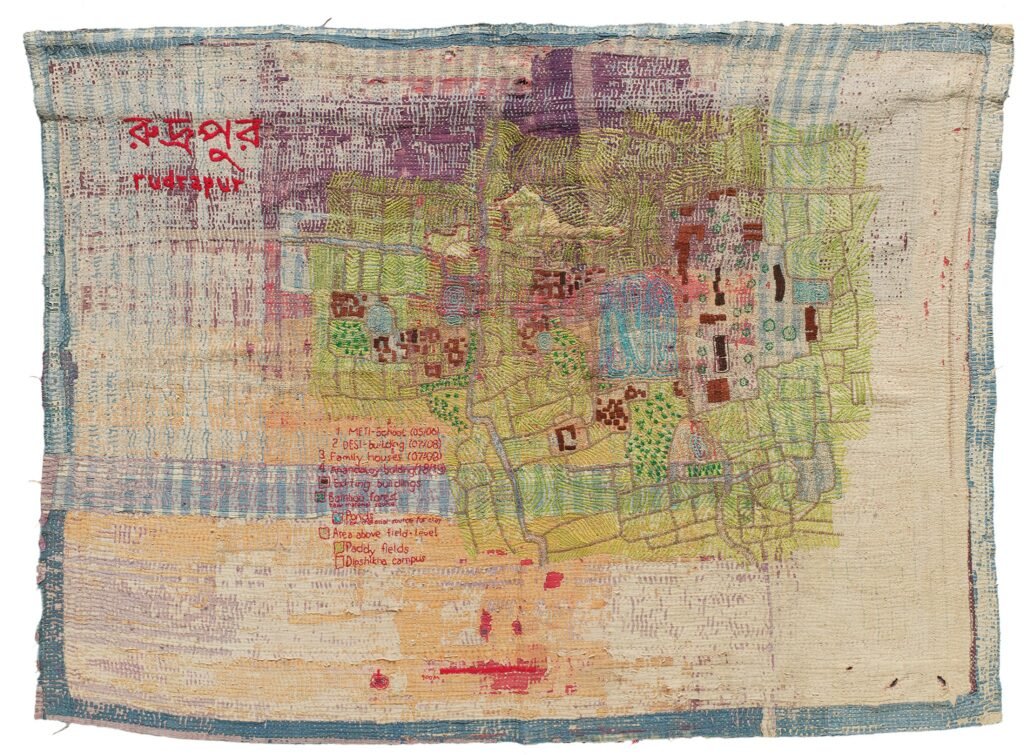

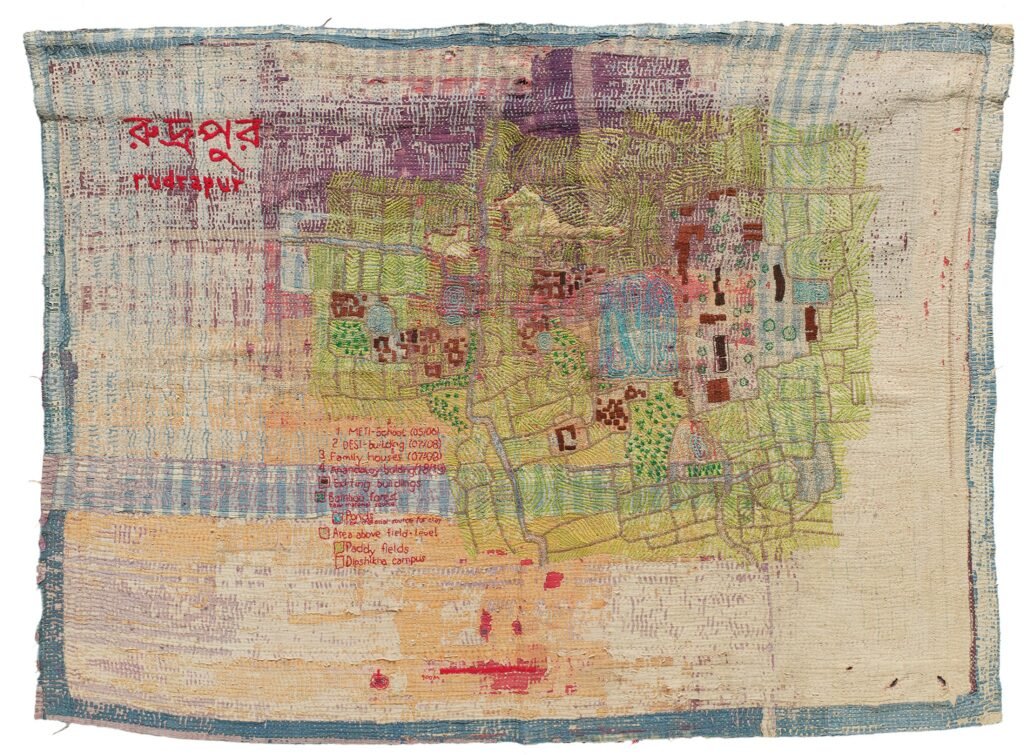

Shuttleworth: Years back, there was one standout moment when somebody submitted a tapestry (Anna Heringer’s Dipdii Textiles, Architecture Drawing Prize 2019). The line work was exquisitely threaded, and it was a fantastic piece of work; it led to the moment where we asked ourselves, is this considered a drawing? We debated at length whether it should be part of the Drawing Prize or whether it was something that should go on a Tapestry Prize or category, which we clearly haven’t got. In the end, we decided it was a drawing, only in place of pencil, ink, or pixels, you have thread forming the imagery on a textile backdrop.

Yeap, that was quite an interesting moment for the Architecture Drawing Prize. It’s a very beautiful and memorable drawing, and it ended up winning the hand-drawn category. It’s about four, five years ago now, but I think every year, you know, there’s always a few surprises. The quality of the drawings goes up, the number of entrants goes up, and so does the range and places where these artworks hail from. It’s gotten a much bigger reach than we originally envisioned. From our point of view, it quite simply is the best architectural drawing prize in the world. We want to make it that, and we’ll always be that.

Let’s now discuss the present. Here’s a question for both of you. With the increasing usage of AI (artificial intelligence) in various fields, it is inevitable that someone might submit an AI-generated artwork for the Architecture Drawing Prize. What are your thoughts on the submission of AI-assisted drawings for the prize? Do you see it as a useful tool for complementing manual drawing or a potential challenge to its essence?

Shuttleworth: I think what’s really interesting about AI is that it has only really come around in the public consciousness in the last year or so; we haven’t experienced that with the Drawing Prize as of yet. But I think what we’re interested in is what those AI submissions could be. So, do we create another category for AI? So that’s what we’re thinking about right now. We’ve got about a year to think about it, so we’ve got time to hash out what the rules would be for that category. But yeah, at the end of the day, it’s a tool, just like how the pencil and the mouse are tools. It’s part of the process of evolution; it’s like, you know, how we went from drawing boards to computers in architecture, and now computers are making the leap to AI. So as far as I’m concerned, it’s got to be explored, and to find out what it can and can’t do.

Infante: On my end, I am really skeptical about AI. I was intentionally trying to avoid reading about it because I think, for people who have been making a life or have been drawing for the longest time, it’s kind of scary, especially with some articles saying that AI may put an end to it.

Technological advancements are a given, as we’ve seen in our history as a race, and we are yet again on the verge of seeing the phenomena of men being potentially replaced by machines. It’s still too early to say how AI will pan out, and we don’t know where we are going just yet. I can, however, see the benefits of how AI technologies can empower individuals who may have the vision but not the talent to communicate something artistically; you can now just type a few worded prompts into an AI model, and it can churn out what you have in mind in seconds. I am, however, heartened that programs like the Architecture Drawing Prize continue to celebrate the act of hand drawing even amidst the rise of new means of expression and communication. At the end of the day, whatever the medium, our works should serve to inspire or provoke an emotional response. Human warmth should be preserved.

Shuttleworth: We’re on the road for an exploration, and as Eldry says, we don’t know just yet where this journey will lead. It may, if it’s allowed, it may become the most important thing in the world, and we just don’t know. What’s fantastic about architecture is always that exploration, always, you know, always moving ahead; there’s always something more interesting around the corner that you need to solve, and I think AI will just help us do that. But at the end of the day you won’t get it to design the buildings in its entirety, no. At the end of the day, you have to acknowledge that you’re designing for a human experience.

In the last few editions of the prize, was there a discernible trend or common theme from the works and people who have been submitting?

Shuttleworth: Right, the interesting thing now is that a majority of submissions are illustrations of existing buildings or fantastical spaces and ideas. There aren’t any drawings coming off projects being built now, which, personally, would be a great thing to try and get back to.

When you are designing a building, you’re doing drawings. It would be great to see them! Both hand drawings and digital sketches. I think you would get a good grasp of what’s actually happening in the architectural world based on the drawings that are presently on the drawing boards or the computers of studios. Architects love to parse projects, as seen in detail drawings, sections, elevations…The drawings also allow a greater appreciation and understanding of the design decisions made by its creators.

Indeed! Unfortunately, we will have to end our conversation now. Mr. Shuttleworth, could you share your vision for the future of the Architectural Drawing Prize with us? Will we see any new categories or changes in the near future?

Shuttleworth: I think we’re discussing whether we should have an AI category and how it would work. We’ll be having a debate over the next few months. However, we won’t ever drop the hand-drawn category. The digital category will always be there, but it depends on how the digital side of life changes. Will it all be AI? Can you distinguish between AI and computer-generated and digital? Is there even a line that you could define? We don’t know yet, but one thing is certain: the act of drawing will always prevail, and the power it holds to communicate and inspire, regardless of the tools used, is something we will always celebrate and look out for. •