Images Buensalido Architects

Update: The Interweave Building is also up for the Best in Color Prize at the World Architecture Festival! Congratulations, Team B+A!

Representatives of over 180 finalist projects from 40 countries will compete live in front of a judging panel on December 1-3 to decide who gets named World Architecture Festival 2021’s Future Building of the Year. To get there, Filipino architect Jason Buensalido and his team must first win in their category. This is done on the first two days of the festival, when three-man jury panels listen and ask questions of each architect shortlisted in each category—Civic, Commercial-Mixed Use, Competition Entries, Culture, Education, Experimental, Health, House, Infrastructure, Leisure-Led Development, Masterplanning, Office, and Residential. The winners of the thirteen categories then face a Super Jury on the festival’s last day to vie for the top prize.

Who are Buensalido Architects up against in the Competition Entry category? Fourteen other shortlisted firms, half of whom submitted conceptual designs for projects in Middle Eastern countries UAE, Iran, Bahrain, and Saudi Arabia.

Should Buensalido Architects win their category, they just might compete against fellow Filipinos if they, too, win their categories. They are: HANDS – Habúlan and Ngo Design Studio shortlisted for Farms for Feasts in Bonifacio Global City, Taguig, in the Civic category; Carlo Calma Consultancy for Cagbalete Sand Clusters, Mauban City, Quezon Province, in the Experimental category; and WTA Architecture and Design Studio for Horizon Manila, Manila, in the Masterplanning category.

Buensalido’s project was their submission to a design competition for the Freedom Memorial Museum, a Human Rights Violations Victims’ Memorial Commission project. Below is Buensalido’s project description submitted to the WAF, followed by an interview with the firm’s three principal partners.

From Fragmented to Free

The Freedom Memorial Museum was created to honor the lives and sacrifice of those who struggled for freedom, democracy, and human rights during the infamous Martial Law period in the Philippines and to inspire generations to continue defending human rights and democracy.

The inspiration is our fragmented nation, a society of imbalance propagated when absolute, unquestioned, and unchallenged power broke our people apart. Today, due to fabricated truths and altered narratives, a large majority of the younger generation is unaware of the horror brought about by that period in our history. This fragmented condition of our society must be recognized, and our fragmented history remembered in its unaltered truth. Only then can we accept that we are a broken people, and in that brokenness, see hope.

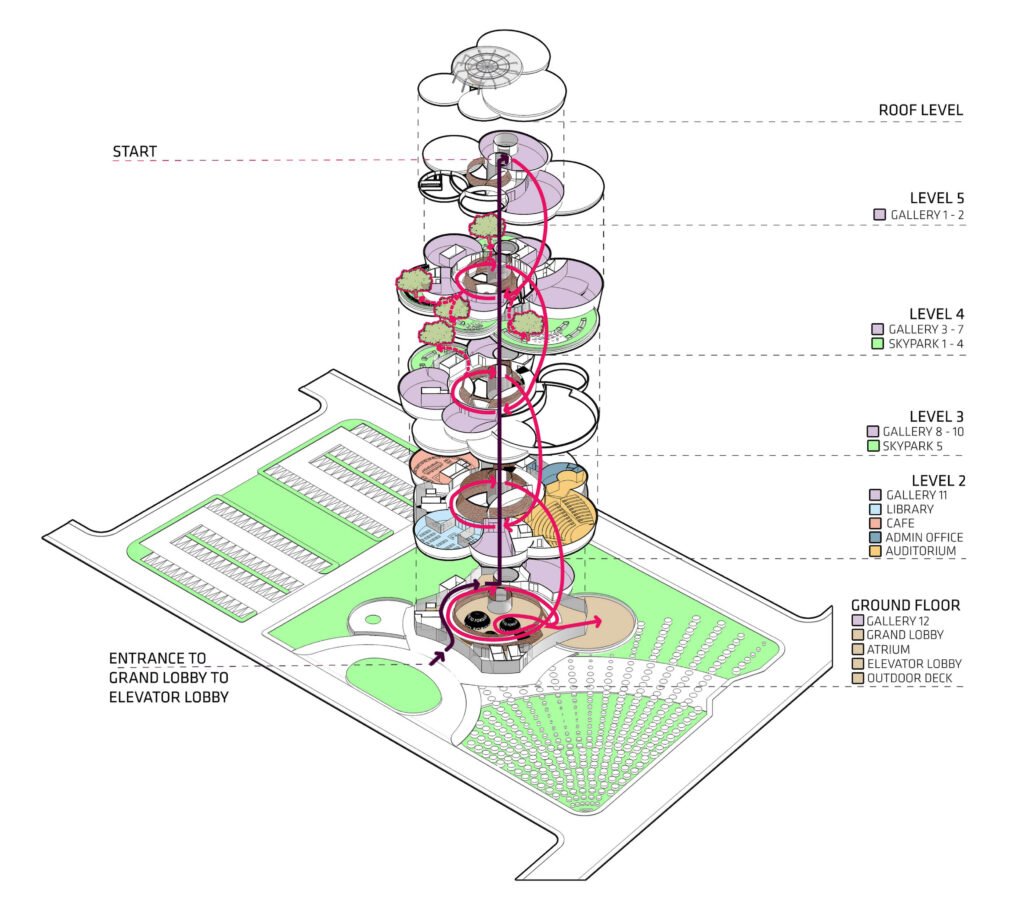

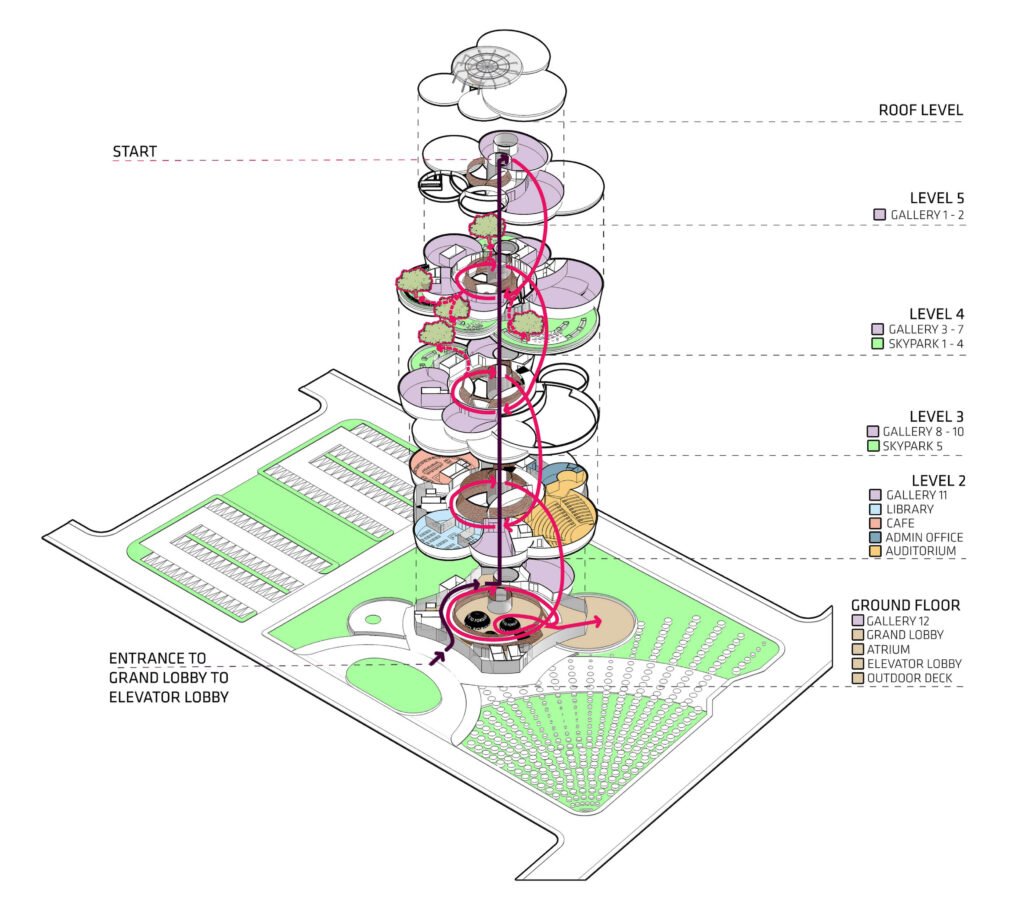

We start with the iconicity of the museum’s form. Set back from the main road and positioned in the center of the site, the structure is a commanding presence, a striking amalgamation of overlapping cylindrical volumes. It seems to be in disarray and chaos (fragmented, even), just as we were during Martial Law.

The circle was selected to be the recurring shape of spaces and forms to symbolize equality, as the shape’s perimeter is equidistant from any point. It also symbolizes the hope for truth due to the absence of “sides” (nothing but truth).

The foreground of the structure is a vast open space covered with round slabs, arranged radially, symbolizing countless unnamed victims of this period. The façade also pays homage to them, with an interspersion of solid surfaces and transparent glass enclosures and sky gardens that allow for light manipulation, and an exterior clad with two-toned stone blocks. It is the hope that as each victim is recognized, one stone is turned from one side to the other, from dark to light, from hopelessness to freedom.

Guests enter through a circular, hermetically sealed lift, surrounded by a seamless LED screen that immerses them in a harrowing collection of images and sounds from Martial Law victims. They alight at the topmost level to go through the different galleries descending a spiral ramp. With the crowd drawn to this single-entry point, the start of the experience is cramped, constrained, and dark—not unlike the state of the nation during Martial Law—but slowly becomes spacious and bright as visitors descend. Light is brought in through the Memorial Wall—a Corten Steel wall that lines the perimeter, with the 11,103 names of victims cut out. Names are sparsely spaced on top and closer together as visitors descend, bringing more light to the experience. This descent from top to bottom will be interspersed by outdoor sky parks, which serve as breathing spaces from the museum’s emotionally heavy content and experience.

The final space is the atrium, a light-filled space with a sculptural piece that asks the question, “Now what?” After the experience, the question hopefully inspires and encourages them to take action and keep this from happening again.

Congratulations, Jason and Nikki Buensalido, Ems Eliseo, and the rest of the team, for making it to the Future Project shortlist!

Jason: Thanks, Judith! We are overwhelmed with the news!

Nikki: Thank you, Judith, and the whole Kanto team. It is a privilege to represent the Philippines in this year’s World Architecture Festival. The team is ecstatic as we all needed a boost and a breather from the challenges of the pandemic—finally, some good news for our community.

Ems: Thank you! We are standing on the shoulders of our fellow Filipino architects and creatives.

You’ve been an active observer of the WAF and the gatherings GROHE Philippines has hosted for shortlisted Filipino architects. What observations have you made that will help you when you present in Lisbon this December?

Jason: I think what would help is rather than having a large event, where the shortlisted entrants would present to a gamut of architects and designers (some of whom are there to just watch and lurk), is to have more intimate and intentional crit sessions. In large events like in the previous ones, in-depth analysis and exchange of thought are quite difficult to occur because of the limited time and an abundance of people asking questions, some of which are not constructive or even analytical. An improvement could be to have a more intimate group of experienced critics listen in and crit the entrant on the project, thought process, presentation methods, and style, all to help the entrant improve and prepare for the actual live presentation. This ‘focus group,’ if you may, can be composed of a combination of experienced architects and designers, educators, thinkers, and past WAF participants, moderated by an experienced individual, all of whom speak the crit language and ethics.

Noted, Jason! I’m certain GROHE and WAF veteran friends would be happy to oblige.

Nikki: I still remember our first trip to the World Architecture Festival in Singapore in 2013. It was a whole new world for me then as we met architects from all over the world who were as passionate about design. Entries from the Philippines were not prevalent back then. Based on the times we’ve watched the crits and our fellow Filipinos defend their projects, the projects that win speak not only of contribution to the aesthetic of the environment but have a bigger purpose, which is the advancement of the community and how the project positively affects its stakeholders. They are altruistic and don’t just benefit the immediate users but also usually disrupt the status quo, transforming the built environment into something better, which gives hope to the community and those who experience the project. The description of the experience, not just the materials or the form of the project, matters a lot. The projects that ultimately make it to the finals are those with purpose that exude emotion and give meaning to life and the built environment.

Ems: Same with Nikki, in 2013. We saw that architecture is definitely more than the physical space—it is how human experiences are formed in that space. So, it would help to highlight how in this project, being a vessel of memories, past experiences are honored, and how those experiences will inform future ones.

How else will you prepare?

Jason: Given that we only have 10 minutes to present the work, we will have to identify the salient points of our entry and tell it in such a way that the judges would really understand the rationale, the essence, and the ideas behind the design; the problems it is hoping to solve, the thoughts it hopes to provoke, and the change it is trying to affect. Our design for the memorial focuses on sequential experiences, so I have to think about how to communicate these feelings to the judges, though to be honest, I still have no idea how to do that at this point.

Ems: We would definitely go back to how we first dissected the project for the design competition, extracted the essences—this project is about memory and moving forward with the guidance of that memory, after all—so we can effectively present how these essences were translated.

Nikki: Of course, preparation is 95% of the work. Being in Lisbon to present to the jury is the icing on the cake. Preparation takes a lot of time, practice, and a good introduction to the project. The heart, passion, and knowledge of the project are already there. The most we can also do is to practice, practice, practice.

It would be prudent to prepare for an online presentation, just in case travel is restricted in December. How differently would you prep for an online versus an in-person presentation?

Jason: I agree. Preparation would be very similar, though. We would focus on extracting and concentrating on the design’s essence and communicating it as best as we can. From what I have observed, WAF presentations have been less about pomp and circumstance and more about content, intent, and meaning. Perhaps ensuring the tech side would be on us rather than the organizers—video quality, audio quality, internet speed, and stability.

Nikki: Yes, I believe this is a good backup. We will try our best to travel by December, but we’d prepare the same way if things turn out otherwise. The advantage of an in-person presentation is emotional connection and presence. Still, I believe that with the right tone, expressions, body language, and facial expressions, this can also be achieved online. A good presentation director is key to a successful online presentation. Content, visuals, and script rather than an impromptu delivery of the presentation, rehearsals, and, of course, an excellent internet connection are the ingredients for us to pull off an online presentation.

Architects talk about designing for the physical, cultural, and climatic context of a future building. Describe for us the emotional context of the design.

Jason: We live in a society of imbalance. Every day, we are forced to live with a significant and continually increasing chasm between social classes. The rich become richer, the poor become poorer, the powerful more powerful, and the powerless even more so. As a result, our people suffer from an inferiority complex combined with a victim mentality that worsens because of this imbalance. This phenomenology began in the Martial Law era, a time of absolute, unquestioned, and unchallenged power that stayed in power by committing human rights violations. Our society is now a consequence of those injustices, a connection that must be clearly told and ingrained in our collective memory.

Tell us about the façade—what’s the story behind your choice of two-toned blocks?

Nikki: We call it a ‘healing façade.’ We know of only 11,103 recognized deaths from human rights abuse. But there are over 70,000 more claimants, unexplained disappearances, or Desaparecidos. Over time, as these victims’ stories are confirmed and recognized, they will be included in the official roll of victims. As each victim is recognized, one stone is turned from one side to the other, from dark to light, from hopelessness to freedom. Healing takes time, and the façade is meant to change as society goes through this process.

Did you recognize any of the 11,103 names to be etched onto the Corten Steel wall? What did you feel, envisioning this wall? As you were designing this, what did you want people, especially relatives, to feel when they see the name of their grandparent, parent, sister, or brother on the wall?

Jason: The actual names were not given to us. So instead of names, I imagined faces and imagined that these faces would never again be seen by their brothers, sisters, parents, children, who lost them abruptly, cruelly, and unjustly. However, the truth is I can never understand the immense and immeasurable sense of loss and grief they have been carrying all this time, being only a baby at the tail end of the Martial Law, which makes it very challenging to navigate this world. The same world forced my elders to live with such heartbreak. So, our hope is that when they see the names of their loved ones on that wall, it becomes an anchor for them to move forward. Not ‘move on,’ though, as I think grief and the sense of loss never entirely depart. But if there is an anchor, some kind of closure, then one may learn to co-exist with it towards prosperity, contentment, and even happiness. As one walks down the dark spiraling halls of the memorial, rays of natural light formed by the cutouts of the names cut through the darkness. The light gradually increases in intensity until one reaches the light-filled atrium, signifying that there is always hope amid adversity and darkness.

Nikki: There were no actual names in the design brief, but they are very important names because they were somebody’s son, daughter, father, mother, family member. We wanted to honor these people and remember how they were a part of our history—how they gave up their lives for something bigger than themselves. I was born after Martial Law and was a baby during the EDSA Revolution, so I can only imagine what these stories hold and how they affected many families. While designing this, I learned so much about this period in our history. How some survived while others were never found. I have met grief, and I imagine how grief lived in the hearts of these affected families. We wanted the wall to be a memory to the future generations, to allow them to feel what the people who fought felt—how, in the face of death, they proudly gave up their lives for the Filipino and for democracy. We hoped that this would serve as a reminder not to take democracy and freedom for granted and that we have the power to choose well.

Ems: Names are powerful and putting names on statistics emphasizes that these are people with idiosyncrasies and histories, not just one among a pile of bodies. The names are cut out from a rusted surface, a weathered, battered plane of experience, if you may, and each one of these persons is freed from this battered existence. By seeing the negative space left behind by the names, one would feel the physical loss, but would also catch the light that replaces the void, like hope and memory that becomes stronger and clearer depending on where you stand, clarity depending on perspective.

What a beautiful description of intent, Ems. Jason, why did you want the visitor’s first experience, which is in the lift, to be nerve-wracking? What happens after the lift? Walk us through the experience.

Jason: The lift is big enough to accommodate a class of 30 people. The video of images and sounds of the cruelty and injustices committed during martial law is meant to disorient the visitors, disarm their emotional shields, prepare them to absorb the seriousness and gravity of what happened then, and allow their spirit to absorb the message of the museum.

Nikki: From a confusing and uneasy visual and auditory collage of images and noise, the elevator door opens at the top floor to silence. Visitors will step out into a solemn and peaceful space with nothing but the original AVESCOM van in the middle with Ninoy on the airport tarmac and some videos of the assassination. In a way, the exhibit starts with what ended martial law.

Have you ever been to a Holocaust Museum? I went to one in Tel Aviv and walked out of there a subversive—determined to question the status quo. That’s not a response most authorities welcome. What impact do you want the Freedom Memorial to have on visitors?

Nikki: I have never been to a Holocaust Museum. Probably the closest one I can relate this to is the 9-11 Memorial in New York. The mood was very somber, and there was a distinct feeling of sadness and pain. I would like the Freedom Memorial to remind the next generation, especially those born after 1986, to understand what had transpired and how history should not repeat itself this way. I would like to remind the next generation how our modern heroes fought and gave up their lives for this democracy, in the hopes that our mistakes will be gleaned and we no longer allow this inhumaneness to be repeated ever again.

Jason: Couldn’t have said it better.

People against this project will say we should learn to forgive. And if we forgive, we must forget. What is your response to that?

Jason: If we forgive, we should never forget. If we erase something from our memory—a mistake, a transgression, cruelty, injustice, loss of human rights, and democracy—then it may happen again. We have to remember so we can be better, so we can demand better. We HAVE to remember to protect future generations from falling into the same darkness.

Nikki: I think real forgiveness does not necessarily mean to forget. Real forgiveness is evident in the fruits of our actions. We forgive, and we learn from the past. We take our learnings and transform them into something meaningful for our lives and those affected and the lives of future generations. True forgiveness means that we learn and build character even with the pain and hurt in our hearts. We do not “move on,” but we move forward in time. Forgiveness sometimes leaves a scar that we can never erase. This scar can serve as a reminder of that hurt forever, but true forgiveness is the ability to learn how to live with that scar with the promise of being better and doing better for our children and the future generations to come. Forgetting means to shut down and run away from the thing that caused the hurt.

One is able to show genuine forgiveness over time, like a tree in the forest goes through seasons to grow strong and bear fruit. The fruit is a revelation of the tree’s essence, its genetic composition. So likewise, true forgiveness bears good fruit. There will always be good that comes with the hurt, sorrow, and pain. Like God’s promise, there will always be a rainbow after the rain.

Ems: Forgiveness requires not forgetting, don’t you think? Remembering also reinforces forgiveness because as we think of the slights, we also recall why we forgave. Remembering is honoring—honoring and acknowledging the hurt and the knowledge we gained through the pain; honoring the resolve to forgive and the courage that comes with that act; honoring the possibility of a better world built by better, wiser, undaunted human beings. •

One Response