Images Habúlan and Ngo Design Studio (Hands)

Habúlan and Ngo Design Studio (Hands) is no stranger to the World Architecture Festival (WAF). At the height of the pandemic, the small studio wound up in the longlist for Isolation Transformed, a competition held by the WAF in partnership with PechaKucha, which challenged designers to envision “future post-virus environments.” The studio made a mark with their entry Common Ground, a rethink of local public spaces anchored by four strategies: self-sufficiency, engagement, isolation, and mobility.

Invigorated by their inclusion in the longlist, in a competition that counted design luminaries Sir Norman Foster and Nigel Coates among its jury, Hands made another competition bid for WAF’s next edition. They made the shortlist under the Future Projects Civic category for their entry Farms for Feasts, joining three Pinoy firms: Carlo Calma Consultancy, WTA Architecture and Design Studio, and Buensalido Architects. Competition is tight, even amidst compatriots—Hands’ Farms for Feasts was a strong contender for the WAFX Award’s Food Production Category, which WAF Festival Director Paul Finch described as having a “…lively, interesting form.” Fellow Pinoy shortlister Carlo Calma wound up victorious for that category; he presented his winning project Cagbalete Sand Clusters to the WAFX panel last July 13.

All four Pinoy shortlisted entries, together with Singapore’s Park + Associates, Thailand’s CREATIVE CREWS, LTD., and Studio Sae of Indonesia are in the running for the coveted Future Project of the Year award to be decided after the live crit sessions in December, to be held in Lisbon, Portugal.

Kanto caught up with the busy Hands team for a brief interview on their WAF shortlist placement, the value of joining competitions, and a closer look at their entry, Farms for Feasts. What follows is the firm’s brief description of their project, followed by our interview with studio founding partners, Yonni Habúlan and Maricris Ngo.

Farms for Feasts

In response to intensifying issues of climate change and food scarcity, Farms for Feasts is a net-zero development where emergent technologies in urban agriculture are housed in one location. The development was inspired by the resilience of the farmers—the backbone of the country’s agricultural industry.

Farms for Feasts is a living ecosystem of nature, technology, and architecture

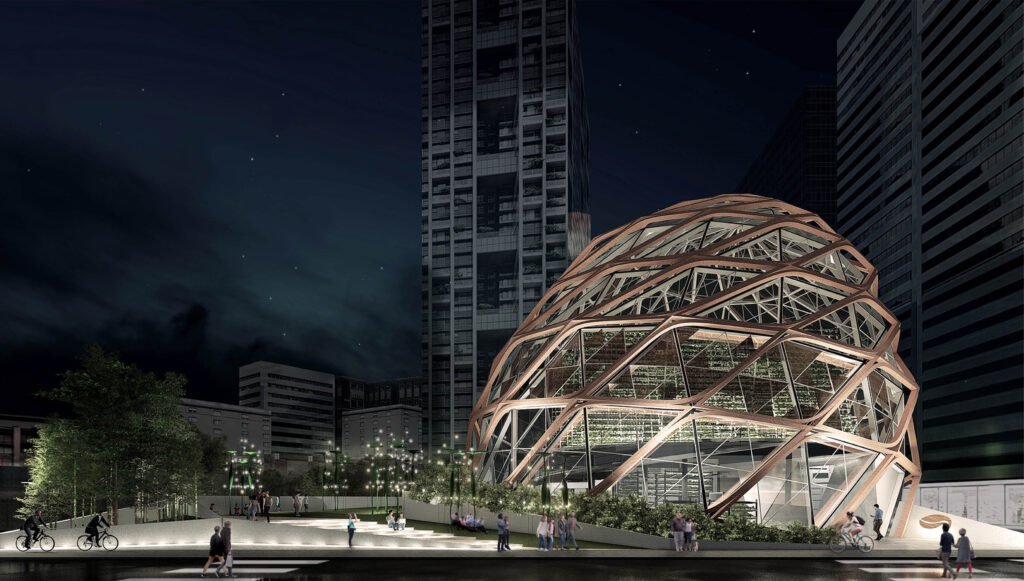

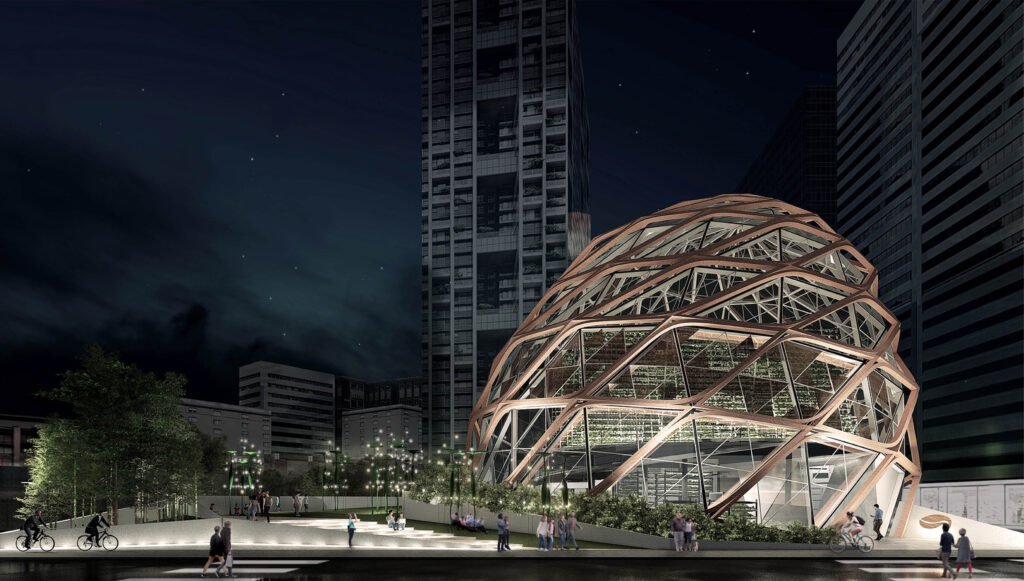

This development envisions the future of farming. Situated in Bonifacio Global City in Taguig, Philippines, Farms for Feasts consists of three major components: the Farm Pavilion, the Energy Plaza, and the Solar Farm.

The project’s principal structure, the Farm Pavilion is strongly defined by its climatic, programmatic, and contextual conditions. It is a two-story volume enveloped by a bespoke elliptical dome—a curvilinear gesture derived from the silhouette of the farmer. This maximizes daylight harvesting required for the produce inside—organized within a collection of massive A-frame structures that ensure optimum cultivation of plants. The lower level contains a multi-purpose venue for farming exhibits and dialogues, as well as storage and production facilities. Harvests from Farms for Feasts will be marketed and distributed to its surrounding commercial establishments. This helps create productive and self-sufficient communities, a model we hope to replicate in other cities within the country.

The Solar Farm maintains the project’s aim for self-sufficiency and a net-zero agenda. A multitude of solar panels is strategically placed to harness optimum solar energy to power the whole development.

The Energy Plaza creates an active space that the public can freely use. It also creates a fitting entry point to the Farm Pavilion, as it provides a large space for interaction and for the appreciation of the pavilion. At the plaza, visitors can use electric bikes, charge their mobile devices thru the solar trees scattered around the area, and simply take in the sights.

Farms for Feasts aims to give the public an involved awareness of urban farming and how this concept can be embedded in their lives.

Congratulations again to your team! It’s your first time to shortlist at the WAF! How do you feel?

Yonni Habúlan and Maricris Ngo: We are greatly humbled to be shortlisted and extremely honored to be given an opportunity to represent our country at the WAF!

Have you joined architectural competitions previously? Why do you think it’s important to put your work out there via competitions?

Yes, our studio has actively joined local and international competitions over the years.

We count ourselves fortunate to have won some and to be chosen as finalists in others. Key recognitions include the Best Architecture Award at the Asia-Pacific Property Awards in 2016, a Merit Award from the Futurarc Architecture Prize in 2019, a Special Mention Award at the Architizer A+ Awards in 2020 (for Farms for Feasts), and for winning the St. Paul Apostle Parish Competition in 2016 (a competition held by the UAP to redesign the said Parish). We’ve also been shortlisted in the following competitions: the YAC Competition – Sports Citadel in 2018, the MADE Architecture Competition in 2015, the MMDA Complex Competition in 2018, the Freedom Memorial Competition in 2019, and being part of the longlist at the WAF Isolation Transformed competition in 2020 (our entry, Common Ground, was our rethink of local public spaces amidst this pandemic).

We join competitions as these allow us to explore new ideas and formulate critical design thinking in different typologies and scenarios. We look at competitions as platforms for experimentation and to further our design research—allowing us to broaden our design portfolio and to create further opportunities for architectural commissions.

What lessons and learnings do you anticipate or hope to get from this experience?

We are optimists and we believe that architecture is a field that flourishes with continuous learning. We intend to take in as much as we can through this experience and become better architects.

What additional preparations or research or improvements to your presentation are you doing for the WAF live crits?

We are currently refining the content of our entry and making sure that we address all concerns of the project. In addition, we are grateful for our colleagues from the industry who have been offering support in preparation for the live crits—especially the past WAF delegates. We know that we will be needing a lot of intellectual and moral support from everyone leading up to WAF. We feel honored to represent our country, alongside our fellow Filipino delegates, and we hope that our contributions would give pride to our nation.

Let’s talk about your shortlisted project, Farms for Feasts. How did you get the project, and out of all the urban areas, why was BGC chosen for the pilot site?

Farms For Feasts was the brainchild of the visionary curator/managing director of the Mind Museum and the Bonifacio Art Foundation Inc., Ms. Maribel Garcia. The project team consists of different specialists in the field of design, engineering, agriculture, and energy. Our studio was tasked to be the Lead Designer and Architect of the project.

The average age of the Filipino farmer is 57 years old. The Philippines identifies itself as an agricultural country, but interest in farming has been dwindling over the years. Farms for Feasts is driven to provide an alternate solution to outdated and inefficient practices. We also aim to empower regular civilians to produce their own food, be active participators in ecology, and show what farming could look like in the Philippine context when it is integrated with daily urban living. This will help make urban farming both environmentally and commercially viable.

Bonifacio Global City in Taguig was chosen as the pilot location to test this idea of sustainable urban farming to permeate in a very organic manner—as its residents are more aware of this practice. In addition, the intended project site is in close proximity to the Mind Museum—the initiator of this development. The project aims to partner with local retailers to distribute the produce that will be harvested from the development, initially within BGC, ultimately spreading out to its surrounding districts and beyond.

While much of the project sounds speculative, most of the technologies necessary to make it happen actually already exist in some form. What do you foresee are the challenges that the project may face in its jump from vision to reality? Who do you imagine the main proponents should be?

To reinvent urban farming, Farms for Feasts requires strong collaboration between multiple disciplines.

It’s true that some of the technological systems introduced in the project already exist but what we did was to apply these in creative ways and through different scales. For example, the main pavilion houses a self-sufficient hydroponics system distributed into massive A-frame structures—each eight meters tall. In spite of its size, we are able to support this system with low-impact methods for cyclical intake and outtake of resources. Water is used and reused throughout the building for nourishing the plants, maintaining a cool environment within the structure, and for the plumbing.

In addition, our team not only addressed the functional requirements of the project but also gave utmost importance to aesthetics, giving a utilitarian building a strong visual identity, one that we want people to associate with innovation, sustainability and efficient food production practices.

We understand that innovations initially face objections. However, our team strongly believes in the project and is one in pursuing this vision to realization. Backed by the Mind Museum and its stakeholders, we are optimistic that this project will be positively accepted by the general public upon completion—given its potential social and cultural significance to the Filipino community.

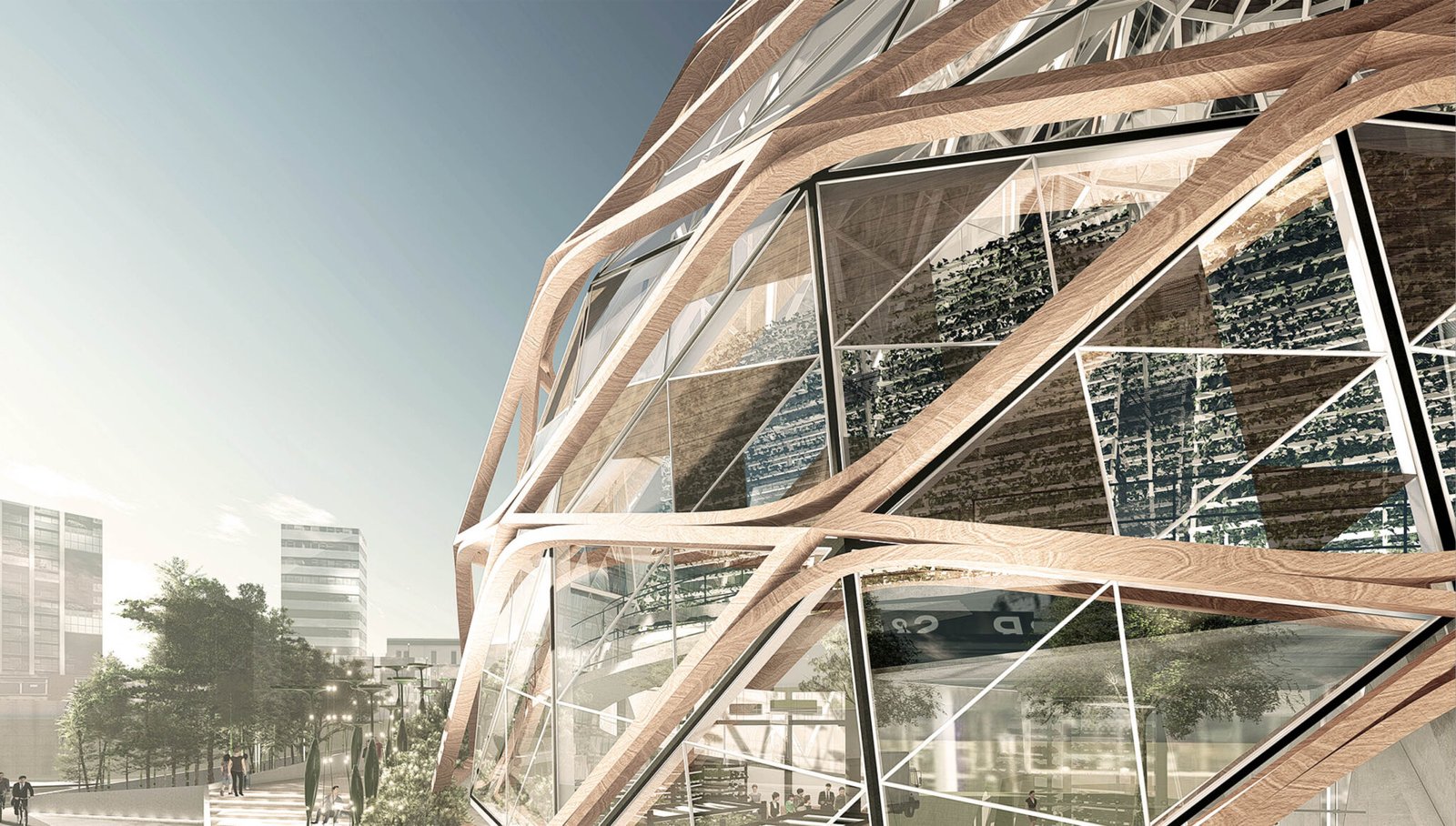

The project comes with a striking elliptical dome finished with a patchwork of glass, steel, and glulam timber. Aside from being inspired by the hunched silhouette of a farmer, what other considerations and functional aspects led to this shape?

The “farmer” is one of the key concepts that drove the design of the Farm Pavilion, but other than just conceptual abstraction, the form of the pavilion was also dictated by performance factors.

The introduction of a dome structure maximizes daylight harvesting required for the produce inside—organized within a collection of massive A-frame structures that ensure optimum cultivation of the plants through an efficient hydroponics system.

The pavilion’s high-performance building envelope maintains the farm’s environs through passive technological systems. Triangulated, double-glazed facets adhered with solar film maximize sunlight transmittance by 87% while blocking excessive heat from entering the facade.

What are the specific urban conditions and contextual requirements necessary for the scheme to work? Will there be options to personalize the look, materials, and features of each urban farm to express a location’s cultural and social context?

Farms for Feasts was never intended to be a one-off project. Rather, its aim was to be the forerunner in creating a new take on the urban farm typology—one that functions well but is aesthetically interesting and engaging. Developing Farms for Feasts in BGC is just the beginning. The goal of our client is to have this as a benchmark for future progressions—one that can be adapted to different social and cultural contexts.

In the future, personalization on certain aspects may be considered, but the key design features and systems should remain intact.

What sort of crops and produce do you envision growing in these facilities? How is the facility equipped to handle the differing climatic needs of multiple produce types?

By creating and maintaining a protected and technologically-controlled environment, the farm will be able to turn out fresh produce of consistent supply and quality.

Housed within the Farm Pavilion, a hydroponics farm is laid out across nine massive A-frames, each standing eight meters tall. In comparison to soil-based farming, it uses 70-95% less fresh water, while producing 40% more plants viable for harvest. The A-frames produce a projected combined output of 1.2 metric tons to 2.5 metric tons of vegetation every month, intended to be distributed to restaurants and supermarkets in the surrounding vicinity.

Temperature is further regulated by evaporative pads interspersed with the glass, as well as exhaust fans above the A-frames. This ventilating system takes in air from the building exterior and cools it down to the optimal temperature of 27-29 degrees Celsius—exhibiting a 30-40% decrease. In theory, one won’t need to go to Baguio anymore to harvest strawberries, as these can already be cultivated within the building.

It is admirable that you also sought to address the public’s lack of awareness of how food is produced via the pavilion’s openness to the public and the complementary facilities that support public education on the matter. What learnings about farming, food production, and public perception have you gleaned from your experience on the project?

Our client had always envisioned the project as a venue of education, exploration, and practice. The resulting architecture was the product of this programmatic hybrid. Beyond public access, it is also vital that the community be properly educated on the advantages of urban farming and how its practice would eventually lead to a more sustainable existence. This educative and performative approach helps bridge the gap between consumers and producers of food.

The current pandemic has exposed the failings of many of our present systems; we believe this project offers a progressive and sustainable way to deal with the issues of food production and security within the urban context, while also strengthening bonds within the community. •

3 Responses