Interview Patrick Kasingsing (Philippine Pavilion)

Images Philippine Arts in Venice Biennale – National Commission for Culture and the Arts

and the La Biennale di Venezia (Marco Zorzanello)

Illustrations Eldry John Infante

Good day, Ms. Choie and The Architecture Collective! I Hope Venice’s been treating you well. For our readers, can you brief us on the overall concept for the Philippine Pavilion?

Choie Funk, curator of the Philippine Pavilion for the Venice Architecture Biennale 2023: First off, thank you, Patrick, for this opportunity to deepen our understanding of what we are doing. These four guys (Bien Alvarez, Matthew Gan, Lyle La Madrid, and Noel Narciso) and many others have been working on this project since 2018 when we were still in Benilde. We joined Global Summer School (GSS) which is spearheaded by the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia (IAAC) in Barcelona, Spain where we were given the brief that we should nominate a societal problem. The theme in 2018 was AI or Artificial Intelligence, which is very much talked about and even feared at present. As AI was something that people can still control back then, we wanted to make use of technology to solve current problems. We had a group of students from Benilde who we invited. We agreed on many societal problems that we could take on, but we eventually decided on solid waste management.

Initially, we thought that it was something that we simply wanted to address. We were concerned and we honestly also believed that this was limited to people throwing objects at the esteros (tidal channels). Later on, as we researched and talked to people and tried to understand the situation, we found that it is something that people have actually learned to live with.

We then started to formulate a concept. For us, in one word, the concept of the Philippine Pavilion is about relationships. Whether it is our relationship with the environment, with the communities we work with, or with each other as designers. As architects, we wanted to do architecture in the service of building communities by creating spaces.

For our partner community (Barangays 739, 750, and 751 of Manila), I think people do not really understand what they’re going through. The running theme of livelihood in the Philippines is survival. If people just do everything to survive, there is no place and physical space for discourse and dialogue; nothing gets solved. This is something that the people in the community also noticed.

We have been with the community since 2018-2019 and stayed even during the pandemic until we found a solution. After all this time, we were able to establish a relationship. We could not have done this without the social development workers. Among those who stayed is Arnold Rañada, who is a development worker and a community organizer. In discussions with other architects, we’re used to the architect being the prime professional and we usually are the ones who dictate. Now, we have to listen to the people. This is very important to learn.

Indeed. I understand that the bamboo-based design solution for this estuary is shaped to address the specific conditions of its target community. How was it ‘repackaged’ as a pavilion for the biennale and how was it done in a manner that its crux for existence is still understood and not lost?

Ar. Lyle La Madrid: I think repackaged is not the term. From GSS 2018-2019 and to the Philippine Pavilion, it is more of a developmental process that we’ve gone through. In the first GSS, the product was literally a conceptual net over the estero to prevent people from throwing stuff in it. It was very conceptual because we cannot build that. We tried to make it into a public space and played around with other concepts. But then, in actual architectural form, we realized that it cannot be done. The design itself was not possible.

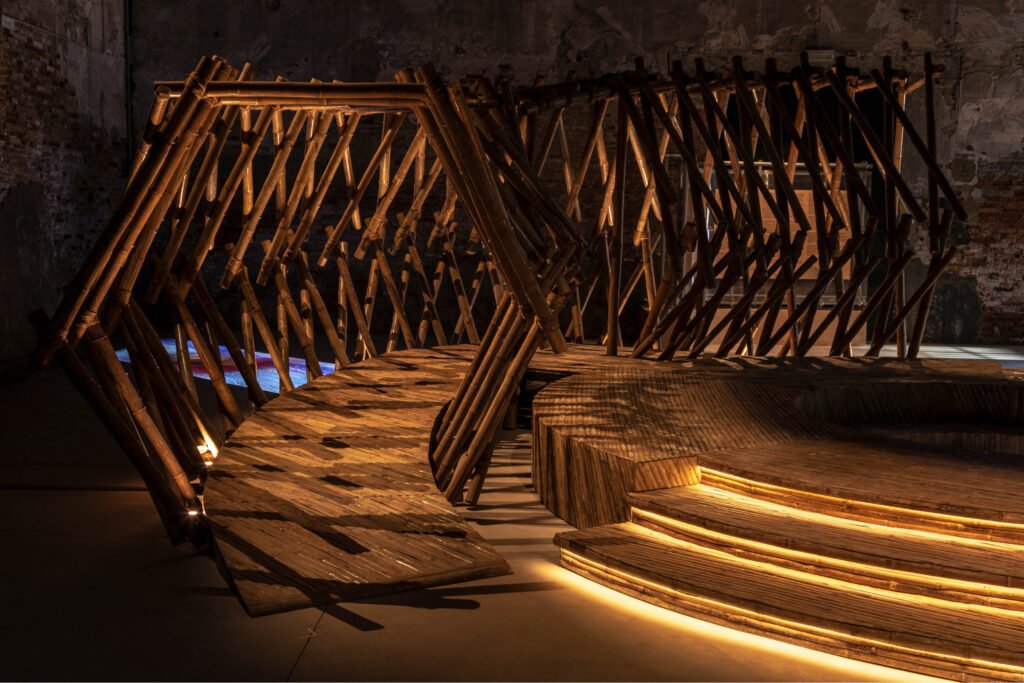

In GSS 2019, with a different set of students and a different theme, we tried to create a more realistic solution. We still played around with the concept of waste and public space. We grouped the students from various universities into five or six teams and we tried to create concepts based on their different ideas and philosophies. That’s how we came up with a solution where it’s a public space and it’s bamboo. The idea revolves around the context of laro, kain, and tambay. But, with that two-week workshop, we only had limited time. In terms of construction, we were limited with regards to the amount of bamboo that we have, the number of resources that we have, and also the amount of skill, because it’s mostly students and the community who helped us out. So, that structure is based on those contexts. In putting the bamboo poles together, we depended on lashing. There was little use of power tools, and the structure did not require skilled workers.

The actual context of the estero itself changed from 2019 to 2022. For this pavilion, we are developing another iteration of the project based on the evolved context. Thinking about the afterlife of the pavilion, we wanted to create something modular—meaning construction methods are easier to teach. And in the context of when it gets back, we will be able to train people to make the joints and cut it in a way that’s easily understandable for skilled workers, not students.

The design right now is informed by simplicity. The structure can be constructed with easy-to-use power tools and does not require much skill. The building method and joint construction employed are undemanding. We created drawings that are accessible to laymen and skilled workers alike. For example, we thought that once we arrived in Venice, there will still be much to do. But even before we arrived, the structure was already done. That points to the efficiency of the drawings and the ease of construction required: the local team was able to put up the pavilion in around one to two weeks, from the expected six weeks.

In the pavilion’s afterlife, the shape may be different. Because we will go through another set of focus group discussions (FGDs) and conversations with our partner community and we will try to, again, understand the context of the site. We are going through the process of developing the system that will make it a lot easier for us to create new iterations of the structure with every new context or community. You can say that what we are showcasing in the Biennale per se is the process that enables the structure more than the product.

Funk: I think it is important to let you know that while we were doing a lot of foot surveys, we found two existing footbridges. We observed that people gathered there at certain times of the day, and how its acts as a temporary community space. Those footbridges are how they get to their residences from the street. The function of this pavilion is very much inspired by those two footbridges. We thought that the community needed more space, so we let it bleed out. We connected them so that people would continue to use the existing footbridges to get to their places and have more space to stay in.

Why is the Philippine Pavilion round? We had a lot of help from curators and the PAVB. Patrick Flores was also our mentor. He advised us to create a physical abstraction. We settled on using a circle as it is indicative of a gathering. In the end, we were happy with how the resulting form communicated this idea of gathering and dialogue, without sacrificing the intent of having a bridge. Still, what you see in the Biennale remains a proposal as it will naturally have to first and foremost, be compatible with the present needs of the community.

The resulting structure is a circular bridge. Let us move beyond the Biennale for a bit and envision the structure on location. The structure you have created was meant to address the accumulation of solid waste in esteros, but as you have also discovered during fieldwork, said structure can double as a communal area, which the barangay lacked. While this is an admirable and wise use of space, how can you satisfy these two goals when there is a danger of the community reverting to the habit of throwing waste into esteros, especially as the structure encourages people to linger?

Funk: When we were asking the people around October (2022) about what they needed, they told us that what they lack are actually burial spaces. If this was a regular project, we could say they cannot do that. But the space belongs to them. When you talk about participative design, it’s not just the community helping build or design the facility, but also managing it. This one is really for them. I think, helping design a space that is really effective and purposeful to the community builds affinity and appreciation for it. The users of the structure will come to care for and treasure the space on their own accord. We think the main problem within these communities, exacerbated by the lack of communal spaces, is that the people don’t communicate; our solution was to give them space to do so. Allowing venues for communication can build stronger interpersonal relationships within the community.

Bien Alvarez: Another way we want to encourage our partner community to be stewards of the water is by connecting them to it. In the past two bridges, there is no access to the water; it’s just a path. What we would like to do once we start the next process is to integrate means by which people can positively interact with the water so they can see its value. Right now, it is treated as an obstacle to cross or a foreign body because it is disconnected from the community. The reason why people often throw their trash on the esteros is because it flows. Out of sight, out of mind. So, we thought, what if our structure engages the esteros more while giving the community the shared space they desired? Maybe then they could learn to manage themselves and police each other and reward people who clean it.

Funk: I recall our conversation with city planning officer Dennis Lacuna; He told us that unless the people realize that the estero is part of their home, they will never clean it up. So, by creating a space that they can use as a community, one that actively engages the estero, then maybe we can be part of the solution.

Noel Narciso: Yes, and this is backed up by our studies from 2018 and 2019; we noticed that when residents have their houses and windows facing the water, they care about the water. But if it is the rear of their homes oriented towards the esteros, they are more likely to throw their trash there. We need to help residents realize that the estero is a vital part of their home and how keeping it clean can contribute to healthier living spaces not just for their families but for the whole community, a sort of public space acupuncture exercise.

Matthew Gan: We also hope to rebuild the community’s relationship with the built environment. As it stands, this relationship is so fragmented that residents do not perceive something as ever-present in their lives as the estero to be part of their space. Maybe a public space acupuncture exercise such as what we have proposed can help reframe how people think about the esteros and imbue the shared space with dignity. I remember back in 2019 when we built our prototype and placed it onsite…we saw the change in how people viewed the space for a while. They would go out of their way to clean up the waterway and take great care of the prototype.

La Madrid: Lastly, we are not forcing anything. The owner of a house has the power to set rules, make sure the space is clean. That sense of ownership in a public space was seen in the observations of GSS 2018. In areas where there are bridges and areas where they used the bridges as public space, it is clean. We are banking on that observation. We are hoping that if we do that same thing and upscale their public space from a bridge to a communal space, they will do the same.

Lashing the bamboo. Photo by Andrea D’Altoe

Installation of the central component of the Philippine Pavilion. Photo by Andrea D’Altoe

One cannot help but notice the parallelisms of exhibiting a work centered on estuaries and the relationships of people with water in a city whose identity and very existence are attributable to water. What observations about cultural attitudes towards water have you gleaned from the experience? How is the Western and Eastern understanding of water’s role in society different or similar?

La Madrid: We did not talk about parallelisms formally. Walking around the city, we have seen the similarities between the urban fabric of Venice and Manila. First is the scale of architecture—the heights of buildings, structures, informal settlements, the widths of the main roads and alleys, and even the doors and windows are the same. For the scale of the estero, there is really a similarity to that of the Pasig River. What I think is the difference between here and there is political will. There is an effective system in place on how to make a city like this work and the citizens respect that.

For the Philippines, it is all over the place. Here in Venice, when you jump into the water, it’s 500 euros. This project is about relationships. And here they use the water in literal ways—kayaks, water buses, and boat markets. That kind of relationship or sense of ownership of the waterways makes it clean. That is not to say that it changes how humans act completely, of course. We have seen people in Venice sweeping their trash to the estero itself. Human instinct is still there. It is how it is governed and how laws are mandated that make a difference. There are guards and police here that would ensure that the rules are being followed. That is what we lack in the Philippines. In our informal settlements, since they are informal, they are just left there to their own devices. There is no government. There are barangays but there are no actual governing bodies to ensure that the community is safe, and the area is clean.

Gan: More than just enforcement, I think Venetians in general recognize the vital role water plays in their existence as an archipelagic city and how it is an indelible part of their identity. There is an unspoken respect for water here, whose omnipresence in this city is embraced with fondness as a feature or a characteristic of their home rather than just an obstacle to bridge.

Funk: Going back to the Philippine Pavilion, one other thing we would like to accomplish with this project is to encourage a shift in attitude regarding how the community perceives itself in relation to the problems plaguing their spaces such as waste disposal. Is the government cleaning up the trash the only solution we can see? In the first place, why are we throwing stuff into the water? Especially things that are not important to us, as if to say the water is not important. We want to help the residents realize not just their role in the problem but how they can be part of the solution. While the government has its role to play in bettering our lives, there are times when the problem can be resolved locally.

We sure have covered a lot of ground outside the pavilion so let us get back to the Arsenale. Aside from what we have already talked about, can you let us in on what constitutes the pavilion’s programming when it launches? What presentations, videos, or activations can visitors expect?

Alvarez: Aside from the main bamboo pavilion, there is also a projection by Jag Garcia which shows some of the outputs from the past FGDs or meetings with the community where kids were asked to illustrate their aspirations and dreams. You could see these drawings floating in the projection, which represents the estero. Interview footage with the communities around the estero such as Barangays 739, 751, and 750 will be there too. There are also archival notes for the exhibition where you could see some of the historical material that went with the exhibition as well as our past studies like the GSS and more recent interactions with the community. Those are the three main elements created by the curatorial team—the pavilion structure, the projection, and the archival notes. You can also find the curatorial note itself within the space wherein you can read about the project. There is also a secret feature that is personal to us. We put benches or bangko, because in a Filipino setting, you put benches, and someone is inevitably going to sit or stay there. I think it’s the smallest component of space in the Philippines. So, around the Philippine Pavilion, we have placed two or three movable benches.

Funk: The pavilion is simple. As we mentioned, it was already put up when we arrived. We simulated an estero that passes underneath, and we did this through a projection mapping that Bien mentioned. The stories that the people themselves recounted during the interviews will be shown there and the historical background shows what got us here. Along with these are their aspirations and proposed solutions.

As you enter the Philippine Pavilion, there is this board that contains the curatorial statement. The statement is stated in three languages for inclusivity purposes and to properly explain the context and the problem. We used solid waste management as our vehicle, but more than that, it is about rekindling the lost relationships between us and the spaces we move in.

Gan: Another aspect of the archival notes is that we reused old windows and projected on them. Part of the intent of using these and projecting data on them is that they essentially function as vignettes, seeing bits and pieces of history, the process, and what led us here. It does not need to be fully understood but it offers glimpses so that people can begin to piece the narrative together and understand without having to be too wordy.

Alvarez: We also took windows from junk shops around the area. It’s like literally bringing parts of that community or the architectural fabric of that community into the Philippine Pavilion.

Funk: Aside from bamboo, we made use of a lot of found materials. We wanted to utilize materials that are friendly or familiar to the residents. Many of the people in the community work with kalakal or discarded items. We looked at secondhand lumber shops and sourced materials there.

What insights do you wish global visitors will bring home with them after their experience of the Philippine Pavilion?

Funk: The way I see it, there will always be problems. But if we create the space to talk about it, then we are a step closer to a solution. The pandemic also taught us to slow down and sometimes be silent and be present. Be there. Create friendships. If there is no space, we cannot do that.

La Madrid: The project is community-focused from the get-go. To backtrack a bit, GSS 2018-2019 is about technology and advanced architecture. It was about things that we think of when we think of architecture—something tangible, something technological, something material. It is a workshop. When we were doing that, it was quite challenging to come up with output because Ms. Choie has been very firm that she wanted a project that promotes community engagement, one that posits a spatial solution to livability challenges in the Philippines.

One of these problems involved estuaries. When we had that talk, we said, “Ms. Choie, it seems difficult to do all this in a two-week workshop. Let us just try to focus on the technology part of GSS and teach parametric design, competition design, etc.” But she was firm and said no. In 2019, we had the same conversation. Again, she saw beyond the technology and homed in on how it can better the perennial issues wracking today’s urban spaces. I never really imagined this project to be displayed and showcased on an international stage.

To answer the question, since it is community-focused, I never really got to think about that part, as I see it as a solution more than a pavilion. But if there was something I would like visitors to take home from this, first, is the value of listening, be it to mentors, to peers, and most importantly, the people you are building with. Second, we waste the potential of the technological advancements we have today if we don’t use them for existing spatial problems and social issues that can benefit from their existence.

Alvarez: What visitors will take away was not necessarily the focus of any of the processes for the structure but what Lyle said could very much be a good end goal. There is also this aspect that our architecture and our urban fabric are contextual and we are reacting to it. Hopefully, visitors of the Philippine Pavilion will understand our context more. At the same time, coming back from the 2018-2019 projects, when we were asked to apply advanced architectural computation design and digital fabrication, I think using it in this context shows heart—not just in our group but as Filipinos.

There is also a sort of democratization of these technological tools. Most people who use these tools are in big studios or big three-letter firms and they are paid a lot and their projects are massive, fancy buildings. But here, we are using those tools for the people, for the public. And we are not necessarily compensated for the use of these tools. This is from us. We are applying these, we are applying ourselves, and at the same time, we are applying it because we believe in what we are doing.

Thanks to Ms. Choie, we have become part of a project that I can wholeheartedly say has relevance, heart, and genuine concern for society. There are very few projects, I think, around the world, that have even tried to do it this way. Yes, people build with bamboo in a lot of places, but utilizing these tools in this kind of setting is very rare.

It is not that we’re entirely selfless, but we believe in what we’re doing. That is one of the things that pushes us. And even though it is not easy, it’s worth doing. So, I hope guests of the Philippine Pavilion will have a glimpse of that and see the beauty of democratizing these tools for the betterment of mankind.

Narciso: I would like the global visitors and viewers of the Philippine Pavilion to really reflect on their relationship with water. The experience of man’s relationship with water in Dubai is so different from that in Venice. There is no water in Dubai. But if you are coming from Singapore, or a developed European nation, for example, water is clean, even straight from the faucet.

One interesting part of the Philippine Pavilion is the centerpiece which is a video projection of a timelapse from sunrise to sunset of how the Estero is used. You will see a projection of children crossing, you will see someone rowing on a boat trying to go around and you will see how sometimes it lags because the debris underneath is very thick. Sometimes you would see someone throwing trash, or you’d hear a motorcycle, or a mother and her child talking, and other conversations in the background. That’s what I mean by reinspecting one’s relationship with water. It is bringing them into the world, literally into the guts of the estuary. That is as raw as it gets. The water projection has no filter. You will see that it’s yellow and green, it is what it is. If you sit at the center of the pavilion, that is really what you see. That is something that I wish people could do, just sit down there, and look at the ‘water.’

On a personal note, I hope this exercise can encourage people to start caring about water again. The answer has always been right before our eyes. Caring about water is what will connect us together as humans in much more sustainable ways, providing foundations for more solid relationships. Because caring is sharing! For millennia, humanity has lived and created communities around water; we still do but now there is distance. It is now something to be crossed, reclaimed, and a lot of times forgotten. It is time we restore our relationship with water.

Beautiful. What better place to preach the gospel of water than in Venice? This is the last question, and I would appreciate it if everyone could answer this. How has the experience of participating in the Biennale shaped you personally?

Funk: I have been following the Biennale since 2015-2016. I was so lucky because I could just take time out on a weekend to visit but now, here we are! I will never get tired of saying that just the experience of the Biennale, I will be forever grateful to the Philippine government for doing this. Having worked concretely with the Philippine Arts in Venice Biennale (PAVB), they have become such experts. They keep on saying that there are still lots to do. But personally, I cannot discount it. There is both pride and responsibility to be part of this. I think I am forever changed by the experience. The support system also warms my heart, I could cry! Thank God to Sudar and Alex (previous proponents of the Philippine Pavilion) who are good friends of mine, as well for their invaluable support and plentiful advice!

Next point, as an architect at the Biennale, I learned that it is not just about being an architect and not about architecture alone. There is a beast out there which is curation, and we have to learn it. The team agreed that it would be great to have it within the architecture curriculum. Architects should be taught how to effectively tell the narrative of whatever architecture they want to put forward. I cannot underscore how important it is to know how to curate because it’s our way of making humanity understand what we want to put forward. Refine, refine, refine. The messaging should not get lost and the structure should not overshadow it. They must work in tandem.

I’m just so very grateful, you know. I think when you are always in this state of gratefulness, you will always be happy. And I am very happy with this exhibition.

I always feel one with the people and the community I am working with. The existing hierarchy where the architect is the head of a project pervades, but we must take out that paradigm. We work with the community. They should be co-designers because they are the users.

Having said that, I also draw a lot of my patience with the Philippines from something I learned from Muhon, our first architecture Biennale appearance. The Philippines is an adolescent society. We talk a lot about how beautiful Venice is and all the other European countries for the most part, but they have been here since forever. We were walking around Verona and saw this stone that had been there since the 1200s.

For us in the Philippines, we must be patient in further knowing our identity. We have to work so much more and inspire others so that bloodlines will continue, and we grow out of our adolescence.

Gan: For me, one important insight in this whole process is that in the Philippines, how architecture is normally practiced is a very top-down process. Architecture, unfortunately, it’s always you seeing or imagining what’s best for the community. The 2023 Philippine Pavilion is a slightly different approach; it is from the ground up and it involves a lot of back-and-forth interactions with the community—talking about ideas that would normally, in pursuit of a timeline, be dismissed. It is something very enriching, heart-warming and ultimately rewarding as what the community gets is closest to what they want as opposed to us designers prescribing a solution solely from our lens.

Architecture does not need to be dictatorial. It should be by the people and for the people for it to achieve humanity. I hope this is something the industry as a whole considers more as not only do, we feel it would make for better architecture, but also create architecture for the better.

Alvarez: I am not an architect yet. I am still studying architecture. I think when you enter the field of architecture, you must be full of hope, to begin with. You must be hopeful just for you to go into that field. If you do not have an ounce of hope in you, don’t go into architecture.

At the same time, my experience at the Biennale started way before this project was selected. For me, it started years ago. These guys are my friends, Ms. Choie, I consider my friend. We worked closely together. I think the entire experience of building the Philippine Pavilion not only shapes me now but also shaped me a long time ago. A lot of who I am as a person today, I attribute to these people. I learned pretty much how to be a good human being from Ms. Choie, how to be disciplined from Noel, how to think out of the box I get from Matt, and how to be a lot of other things I get from Lyle.

Narciso: Two things: the first one is that it is difficult to achieve elegance through simplicity. What you are seeing in the Philippine Pavilion is a process. It is the product of a process, it is a chapter of the process. Being the one behind the drawings and the actual construction system of the Philippine Pavilion now…creating those technical systems and making sure that it is multipliable…that it can actually be executed in different contexts with the materials that we have like bamboo, steel, and wood…being able to create a computation design system to make this achievable, executable, and one-is-to-one…That’s hard. To be able to communicate all these in construction drawings and condense them into a simple manual that you would think was made by IKEA, that is difficult. Simplifying complexity is naturally difficult but when you do, you will have achieved elegance.

If you get the system right, it makes it usable for so many people. And the beauty of this system is that it outlives you and can even take a life of its own. It can work with other architects too, for example. The beauty lies in the system’s generosity and its capacity to keep giving beyond its creators.

The second point that I have is that we want to communicate is not just about having hope. It is also about questioning assumptions. For example, we always say in the Philippines that the government is the problem. It is so easy to blame things, it’s the cheap and easy option. But what if the government is giving architects an avenue and platform such as the PAVB, to surface and posit solutions about actual issues? What if the government can help?

We must strike up these conversations because how will we achieve developed status as a country if we don’t confront these issues upfront, opting to avoid or censor them out of our vision? As architects, we can bridge the discourse that can enable solutions to a whole host of urban realm problems. But only if we learn to stop and listen first.

It is time we start asking questions again and reexamining our relationships with water, architecture, and people.

La Madrid: This is very personal to me, and I even got teary-eyed the first time I was trying to explain this. This whole experience changed the way I see and practice architecture. Earlier in this interview, I mentioned my conversation with Ms. Choie wherein I was telling her that the GSS was a workshop on advanced architecture, and we should not be doing social architecture. With Ms. Choie, advanced architecture is not about technology. It is about empathy. When you think about architecture and what we learned in architecture school, you would think that architecture is all about aesthetics. But no, it is about uplifting people’s lives with dignified shelter. Of expressing empathy for the other and making use of one’s skillset to shelter them.

In the Philippines, architecture can only be afforded by the wealthy. When someone discloses their fees, it filters who can afford architecture. Even if the fees were lowered to a certain point, it is still way beyond the pay grade of a huge chunk of society.

For work, I design residences in exclusive villages with thousand-square-meter lots, with two to five bedrooms, two kitchens, and other creature comforts for a household of two to five people. When I think about how dense and suffocating the architecture is in the community around the esteros, how 500 people can fit within that 1,000 square meter lot that I am designing for, it really hits differently.

(Pauses)

When you see it in person and when you do architecture the way we did, and we are given a platform to share this process and our experiences, it is just different, overwhelming, and also freeing for me as a practitioner.

My old lens is forever shattered. I now see the harsh realities that surround me, and I am no longer just a bystander. I behold the struggle, but I can be an active part of the solution. That is why it is personal.

I am so sorry I made you cry! But thank you for sharing that! I am sure there are many others faced with a similar quandary, but your experience shows that avenues exist to use architecture that uplifts and benefits the many and not just the few who can ‘afford’ it.

La Madrid: The 2023 Philippine Pavilion democratizes architecture. Its entire process democratizes architecture in a way that we architects are just mediators of the architecture. Instead of us prescriptive, we help mediate what architecture is for the people. That is really what this is all about.

And this process will outlast you and your team beyond the Biennale. Your legacy of giving is all but assured. Beyond just creating a building that can be demolished, you have all produced something with permanence because it is a body of knowledge that resides and grows within people. Congratulations again and kudos to all the great work flying the country’s flag in Venice! Thank you all, for your time! •

Tripa de Gallina: Guts of Estuary

Curators:

Sam Domingo and Ar. Choie Y. Funk

Exhibitors:

The Architecture Collective (TAC)

Bien Victor M. Alvarez

Matthew Jonathan S. Gan

Ar. Christian Lyle D. La Madrid

Noel Joseph Y. Narciso

Arnold A. Rañada

Collaborator:

Jose Antonio Garcia

In engagement with Barangays 739, 750, and 751 of Manila

Commissioner:

National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA)

in partnership with the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA), and

Office of Senate President Pro Tempore Loren Legarda

2 Responses