Interview and introduction Patrick Kasingsing

Additional information Philippine Arts in Venice Biennale (PAVB)

Images Studio KIM/ILLI and PAVB (Philippine Pavilion Venice Biennale 2025)

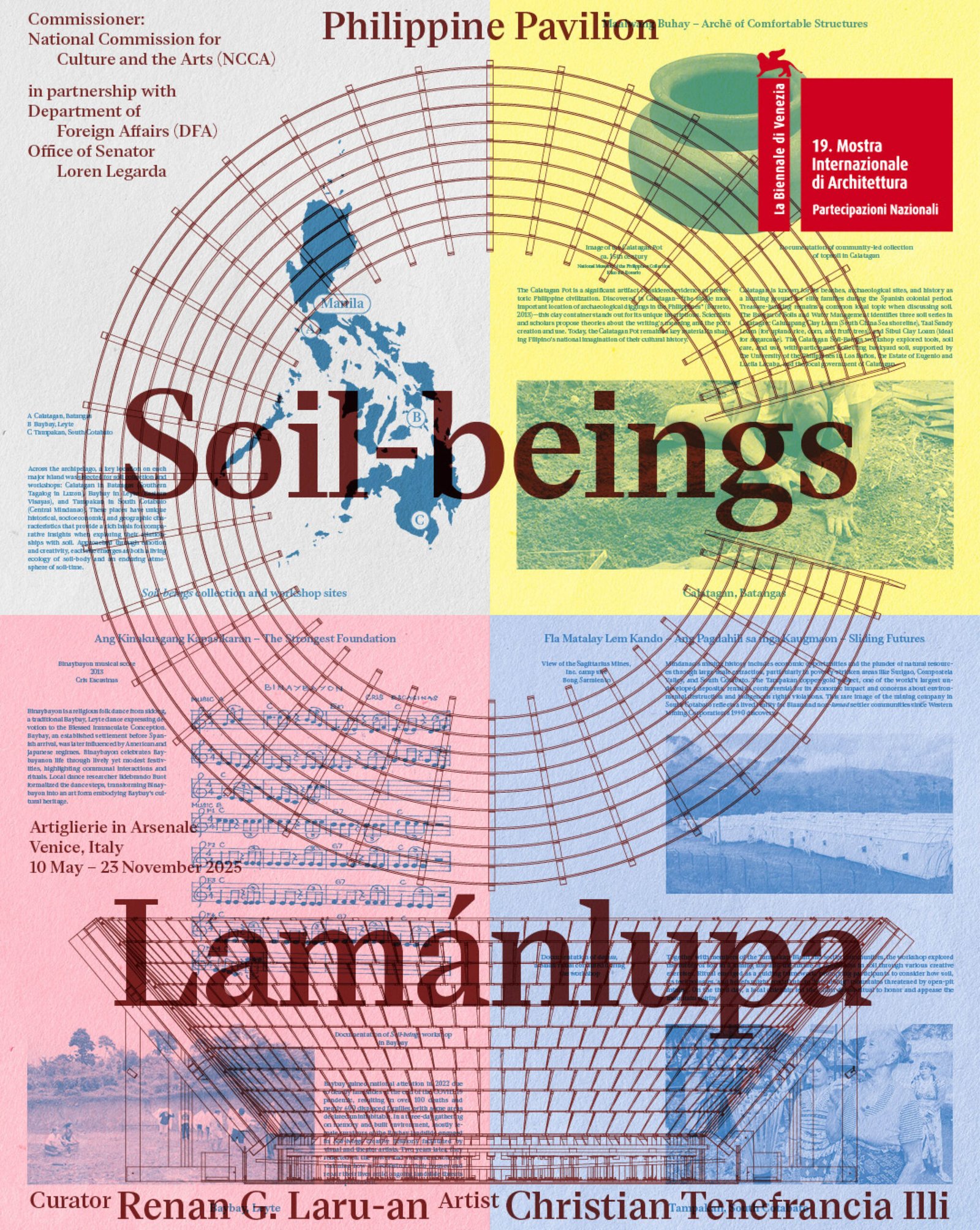

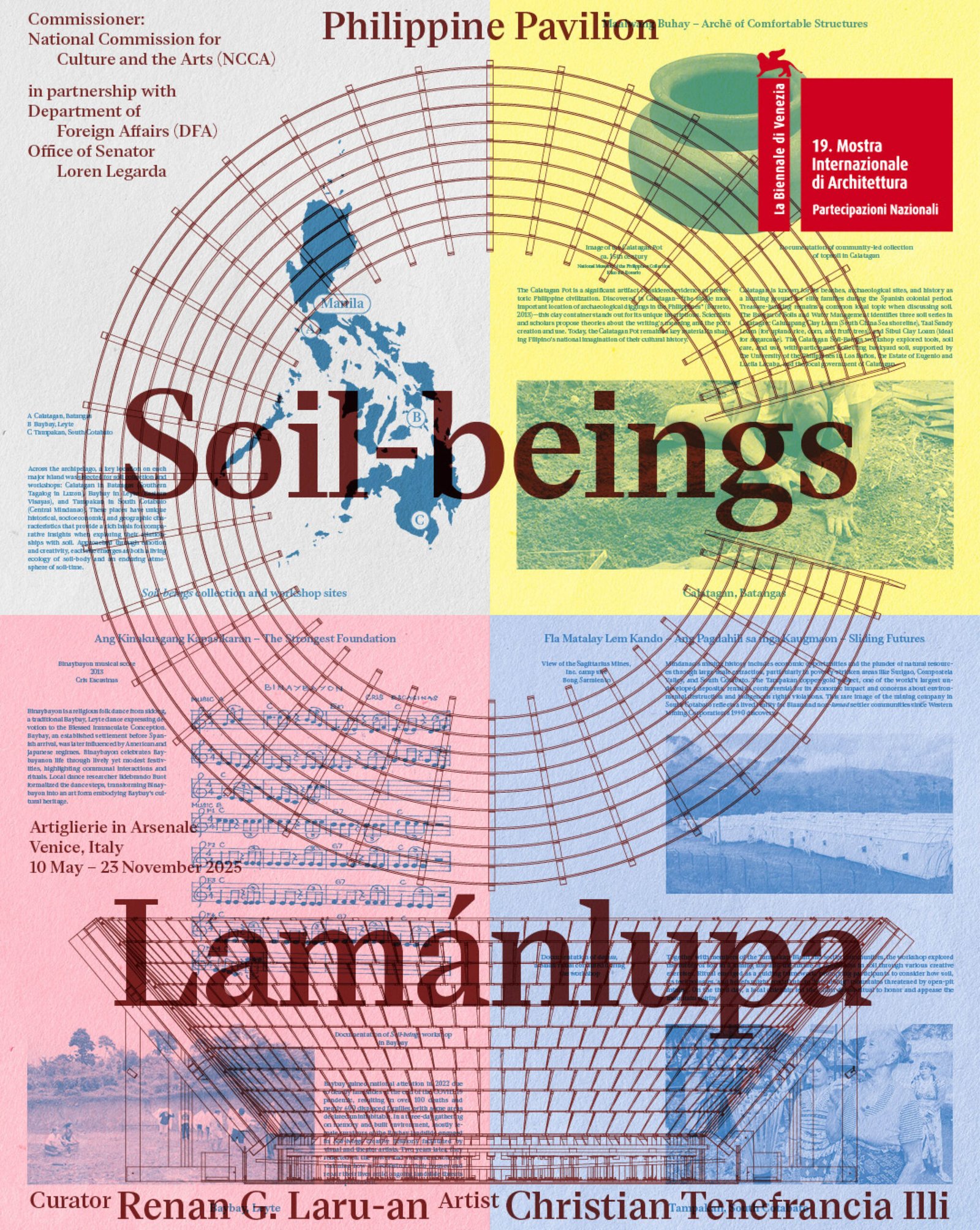

Architecture could not exist without the ground it’s on. It is this belief in the inimitable role of soil—alive and feeling, like the users of the spaces it supports—that forms the crux of the Philippine Pavilion’s curatorial concept for Soil-beings – Lamánlupa at the 19th Venice Architectural Biennale, helmed by curator Renan Laru-an and exhibitor Christian Tenefrancia Illi of Studio KIM/ILLI. The exhibition is a clarion call for introspection, asking: how can architecture adopt a more reciprocal and ethical relationship with the earth?

Visitors entering the room housing the Philippine Pavilion at the Arsenale will come face to face with its centerpiece: Terrarium, a vortex-shaped structure composed of more than a thousand soil samples collected from landscapes across the Philippines. The samples form the walls of a funnel-like space, the result of interdisciplinary engagement with architects, indigenous leaders, artists, and other collaborators. Through research and workshops, the biographies and histories of each soil sample were unearthed, hailing from Metro Manila, Batangas, Leyte, and South Cotabato, among other locations.

Terrarium offers an architectural reversal: soil, typically the invisible support for built space, now becomes the walls that shape it. It evokes what the press release describes as “an experiential encounter with soil’s power and dynamism.” The photos below reveal the startling earthiness of the built space—multihued soil samples cascade down steep slopes within the stark interiors of a centuries-old workshop facility. Visitors enter the vortex through a break in the wall, where they are seemingly engulfed by both the sight and smell of Philippine soil, an experience that is heavy, primal, and palpable. In a conversation with Kanto, Illi speaks of evoking petrichor and initiating microclimates that allow visitors a five-month encounter with weathering, growth, and change across each soil tile.

Soil-beings’ message, while not new, feels especially urgent amid the climatic catastrophes that increasingly mark our daily reality. At the time of writing, the Philippines has just emerged from weeks of relentless rain, with numerous cities and towns inundated by floods and landslides. Rampant deforestation, illegal mining, and corruption have once again been cited as culprits. Yet the land’s exhausted cry—to be treated as collaborator rather than commodity—continues to be drowned out by a seasonal cycle of blame.

Kanto reached out to exhibitor Christian Tenefrancia Illi for a conversation timed with the pavilion’s recent opening. We will update the piece with curator Renan Laru-an’s responses when available.

Groundwork for Soil-beings

Congratulations again, Christian and Renan, for the recent opening of the Philippine Pavilion. Before we dive into a discussion about the pavilion itself, let’s talk beginnings. How did you and Renan Laru-an, your curator, come together for this project? Was this your first time working together? And what would you say made the project the right fit for you?

Christian Tenefrancia Illi, co-founder Studio KIM/ILLI and exhibitor of Soil-beings (Lamanlupa), the Philippine Pavilion at the 19th Venice Architecture Biennale: This project emerged from a convergence of shared urgencies—about the perception of soil, land, extraction, and the politics of matter. Our collaboration for the Philippine Pavilion went beyond complementing each other’s expertise—it wove together different epistemologies and methodologies: grounded in curatorial research, transdisciplinary thinking, rooted in material processes and spatial translation.

Renan and I had engaged in projects before, but this was our first time working together on such a level, from government institutions to grassroots movements. What made this the right fit was our shared belief that soil is not just about the built environment but about the forces that shape it—historically, ecologically, and socially. Soil-beings (Lamánlupa), therefore, is not an object but a site of convergence, a living system for visitors to discover.

Soil is often framed as raw material or historical artifact, notably in the realm of architecture, but Soil-beings positions it as a life force. What does this shift reveal about how we build and inhabit spaces?

Tenefrancia Illi: Yes, soil is commonly perceived as passive—a medium to build upon, to cultivate, or to extract from. But Soil-beings insists on soil as an active agent, a body that breathes, absorbs, and remembers. It carries histories not just in the form of sediment but in the stories of people displaced by extraction, in the residues of colonial infrastructure, in the lingering toxins of industrialization and globalization.

By shifting from soil as a material to soil as a being, we disrupt the dominant narratives of architecture as permanence, hierarchy, and control. Instead, we embrace architecture as flux— porous, impermanent, entangled with decay and regeneration. This challenges the way we think about space by no longer treating it as something that exists despite the land, but because of it.

How does the pavilion’s concept engage with the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale’s theme (Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective.)? Did the project take shape in response to it, as a provocation, or did it develop on its own and later find its resonance?

Tenefrancia Illi: The project took shape independently but found deep resonance with the theme. Soil is an intelligence: a natural archive, a sensor, and a memory bank. It is artificial in the sense that it has been modified, displaced, and contaminated by human intervention. And it is inherently collective, never existing in isolation but always entangled with networks of fungi, bacteria, labor, and politics.

In a Biennale that speculates on ‘artificial intelligence and digital futures’, Soil-beings posits a different question: What if intelligence was already beneath our feet? What if the most urgent knowledge we need is not about transcending nature, but about learning how to listen to it?

Layering soil-stories

Soil carries histories of ownership, displacement, and ecological collapse. Can you elaborate a bit on whether Soil-beings confront these issues head-on, engage with them more abstractly, or try to strike a balance?

Tenefrancia Illi: It does all three. Soil-beings is a confrontation. It refuses to aestheticize soil without acknowledging the histories embedded within it. But it is also a space for reflection, allowing visitors to experience these histories in a way that is not didactic but affective, sensorial, and embodied.

Soil-beings is also a site of friction: between soil as nourishment and soil as poison, between soil as home and soil as a site of forced migration, between soil as commons and soil as property. It does not resolve these tensions but makes them impossible to ignore.

Given architecture’s undeniable role in climate change and environmental degradation, would you consider your pavilion a provocation? a call to reclaim forgotten wisdom, or something else entirely?

Tenefrancia Illi: It is a provocation, a reclamation, and an experiment all at once. Architecture often sees itself as a force of progress, but with Soil-beings, we venture to ask: What if progress means unbuilding? What if innovation is about returning—not nostalgically, but critically—to ways of relating to soil that have been violently erased/reshaped/transformed?

At the same time, this is not a nostalgic call to “go back to nature.” Soil is already urban, technologized, and political. This iteration of the Philippine Pavilion is about recognizing how we inhabit it and what responsibilities come with that recognition.

On identity and Philippine soil

The international art and architecture world (on top of the expectations of both the local and diasporic Filipino community) often expects a certain “Filipino-ness” in national pavilions. How do you navigate that expectation without feeling boxed in?

Tenefrancia Illi: Soil-beings does not present a single, fixed idea of Filipino identity—it presents an ecosystem of narratives, regional specificities and realities. Each soil tile carries its own context, ecology, and history.

Rather than reducing “Filipino-ness” to a singular image or motif, we offer something messier, more entangled. Filipino identity, like soil, is layered, porous, and forever shifting.

The pavilion is rooted in Philippine soil—literally. What architectural or cultural philosophies shaped its design, and how do you hope those ideas translate to a global audience?

Tenefrancia Illi: That Architecture is not an imposition on land but a dialogue with it—a negotiation of context, histories, and materials. Understanding architecture not as static form but as a process, a cycle of decay, renewal, and transformation.

The Terrarium reflects the Philippines’ diverse topographies—evoking both extraction and cultivation, destruction and repair. Its form draws parallels between open-pit mining and the rice terraces; both human-altered landscapes, yet with vastly different relationships to time and care.

For a global audience, the pavilion serves as an invitation to examine their own complicities and relationships to soil and land.

Realizing Soil-beings

Translating Soil-beings into a physical structure surely came with serious challenges. What was the hardest part of making this vision a reality?

Tenefrancia Illi: Working with living matter is always unpredictable. The logistics of transporting soil—navigating customs, institutions, and contamination protocols—soil that breathes, cracks, shifts, and resists containment. Soil has agency.

Was there a moment in the process when things weren’t working out? How did you navigate that?

Tenefrancia Illi: There were many. Institutional, communicational, curatorial. Regulatory and logistical challenges in transporting soil across borders. Each “failure” became an opportunity to rethink, allowing the project to evolve rather than forcing it into a fixed form.

Soil as collaborator

Working directly with soil, rather than relying on models or representations, alters the conventional way architecture is exhibited. What doors does that open, and what limits does it present?

Tenefrancia Illi: It opens the possibility of experiencing soil and ‘its architecture’ as a living, breathing thing—something that changes over time, that demands care, that refuses to be static. It also forces visitors to engage with soil directly, beyond abstraction.

The challenge, of course, is that soil is unpredictable. It refuses to be ‘preserved’ in the way institutions often demand. But that is precisely the point.

Terrarium’s structure is made of nearly a thousand soil tiles, forming an immersive vortex-like structure. How did you land on this form?

Tenefrancia Illi: The vortex-like structure of the Terrarium is informed by extractivist logic and aesthetics—a self-critical metaphor for the movement and migration of soil: displaced, eroded, transported. It also stands as a symbol of entanglement, of histories spiraling together, and refusing linearity. The tile format, meanwhile, references architecture’s desire to frame and contain, forcing soil into a rectangular, fixed unit. But as we’ve found out, soil resists control; it transforms, shifts, and unsettles the very notion of standardization.

At the same time, the form also serves as a reference to markers of ancient civilization—echoing structures like the rice terraces, which exemplify a more reciprocal relationship between humans and the land. Unlike the extractive grid, the terraces embody a form of co-authorship between nature and culture, a collaboration shaped by care, time, and adaptation.

What kind of interaction do you imagine visitors having with the pavilion?

Tenefrancia Illi: It is meant to be encountered bodily. It invites slowness, contemplation, and both comfort and discomfort. Inhaled in deep breaths, it becomes both an installation to observe and a terrain to traverse. It reverses the concept of the terrarium; is it us putting ourselves at the center of things or is it actually the soil that is observing us? The Philippine Pavilion unsettles this boundary between the ‘built and the organic.’ Like Proust’s madeleine in Remembrance of Things Past, it aims to prompt and awaken forgotten sensations, triggering buried memories through the scent or petrichor, texture, and weight of soil—reconnecting visitors to landscapes they may not even realize they have lost.

Feet on the ground

After everything it took to bring Soil-beings to life, is there a particular moment, before, during or after its ‘birth’ that stands out for you?

Tenefrancia Illi: The moment we realized that soil is connected to literally everything, we can’t resist, we can’t escape it—that was when we truly understood that soil is no inert material, but a living force. It does not conform to our desires, and we must learn to listen to it.

But there was also the moment we finally opened the Philippine Pavilion at the inauguration—after several pre-openings, back-and-forths between Berlin and Venice, and all the layers of negotiation and labor that led to it; to see the work fully manifest and feel its presence, was deeply moving.

One of the most powerful moments came during the opening ceremony, when the Philippine Madrigal Singers ‘activated’ the space. They sang and moved with a circular choreography on the platform of the Terrarium. As each singer turned toward the soil, it felt like an act of spiritual cleansing—a powerful catharsis. It was as if the soil, which had resisted us in so many ways throughout the process, had finally settled, accepted, and allowed us to arrive.

In that moment, our journey with the Pavilion felt whole. •

Soil-beings (Lamánlupa)

Commissioner: National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), in partnership with the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA), and the Office of Senator Loren Legarda

Curator: Renan Laru-an

Exhibitor: Christian Tenefrancia Illi

Venue: Arsenale

10 May – 23 November, 2025

The Curator

Renan Laru-an is a curator and theorist. He creates exhibitionary, public, and research programs that study “insucient” and “subtracted” images, subjects, and artistic works—those unsettled by development and integration projects. The former artistic director of SAVVY Contemporary in Berlin, a founding member of the Philippine Contemporary Art Network (PCAN), and the founder of DiscLab | Research and Criticism, Renan co-curated the 2nd Biennale Matter of Art (2022), the 6th Singapore Biennale (2019), the 8th OK.Video–Indonesia Media Arts Festival in Jakarta (2017), and the Lucban Assembly (2015), as well as other exhibitions with Sharjah Art Foundation, TPAM–Yokohama Performing Arts Meeting, and the UP Vargas Museum. He serves on advisory committees for the Istanbul Biennale and esea contemporary. Born in Sultan Kudarat, Renan currently lives in Berlin.

The Exhibitor

Christian Tenefrancia Illi is a German-Filipino multidisciplinary artist. He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts Munich and received scholarships from the University of Edinburgh (2013) and the University of Arts and Design Karlsruhe (2015). Co-founder of KIM/ILLI, an award-winning transdisciplinary studio working across art, architecture, and design, his practice explores the impact of colonialism and globalization, utilizing time-based media to examine structures and narratives. He won the 1st jury prize in the EDGE East Side Competition (2021) and prize awards in the Art in Architecture competitions of the German Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning. He received residency grants from the Arts Foundation Baden-Württemberg, WKV Stuttgart, Goethe-Institut, and HANGAR.ORG, and presented a solo exhibition during Art Nou (2022) in Barcelona. His work was exhibited at the Japanisches Palais of the Dresden State Art Collections (2024).