Interview and intro Patrick Kasingsing

Images Greg Mayo and Patrick Kasingsing

I first met [arguably] the Philippines’ biggest Art Deco champion, Ivan Man Dy, in person when he invited me to co-bill a talk for the Heritage Conservation Society in 2018. The topic juxtaposed two modern architectural styles: the material honesty of Brutalism, which I introduced, and the ornamental geometries of Art Deco, which Ivan customarily presented with his trademark passion and energy to a crowd that spanned young and old at First United Building.

I saw firsthand not only Ivan’s encyclopedic grasp of Art Deco, but also how he channels this hard-earned knowledge to inform and inspire a new generation of heritage advocates. His obsession with the style has been the subject of numerous articles, interviews, and documentaries — a fascination rooted in his work as a tourism practitioner and heritage advocate, and one that crystallized with the loss of a local Art Deco icon, the Jai Alai Building in 2000.

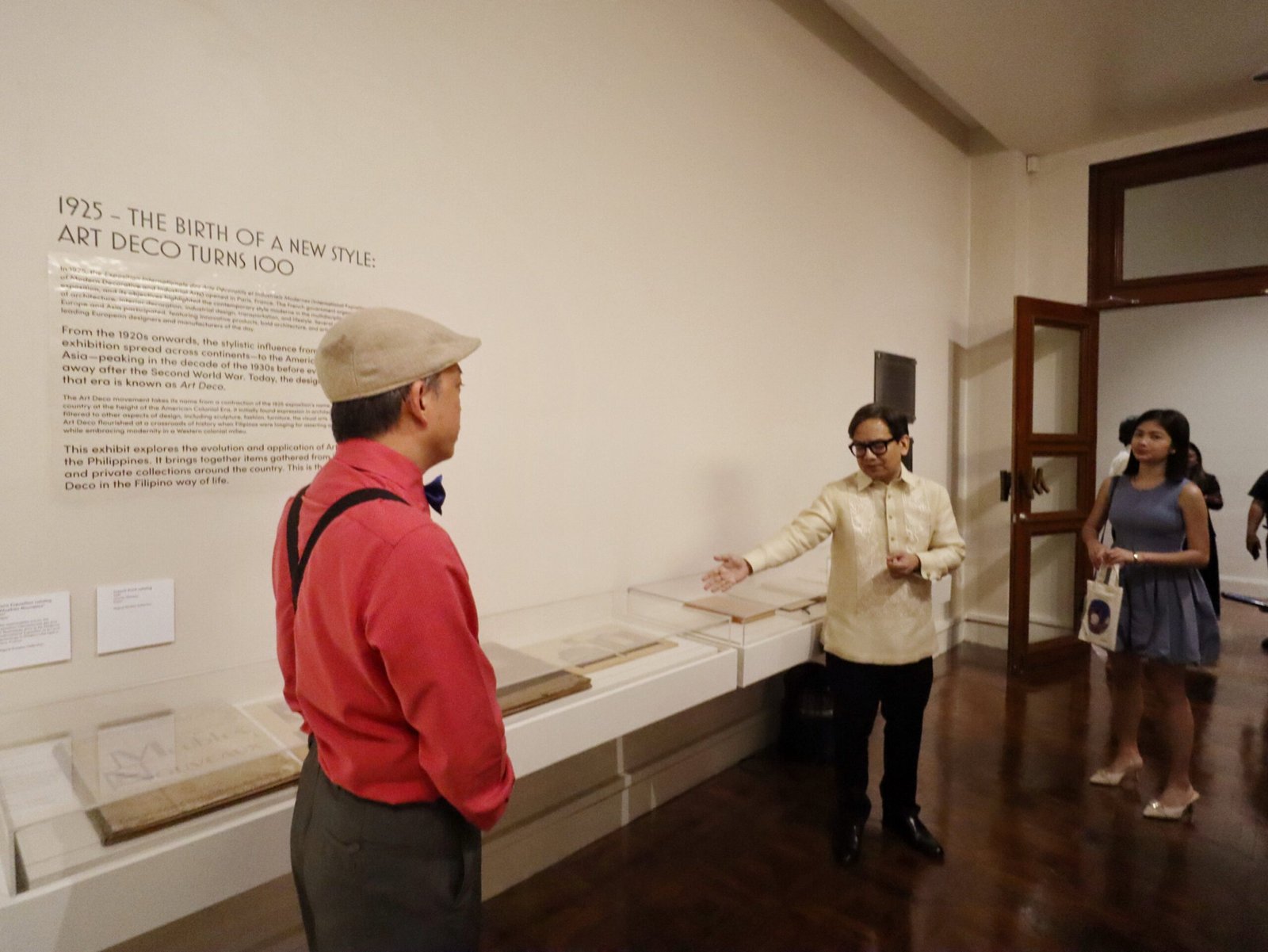

You can read a more comprehensive chat I had with Ivan on Art Deco here, but in the conversation that follows, I get to quiz and celebrate him on this milestone exhibition: the largest single show ever staged on the movement by the National Museum, featuring 300 objects sourced from across the country and beyond, spread across two galleries, and timed for the style’s centenary. And perhaps most surprisingly, for a man who has spent decades researching, publishing, and breathing Art Deco through talks and tours, this marks his very first museum-grade show devoted entirely to his pet subject.

In the interview that follows, Ivan walks us through the story behind the objects, the galleries, and the passion that drives his lifelong advocacy — which has now led to this exuberant celebration of Philippine Art Deco, 100 years after and nearly 7,000 miles away from its birthplace of Paris. •

Happy to have you back at Kanto, Ivan! Your association with the Art Deco style is common knowledge, but for the remaining few who need a briefer: What was the moment or discovery that made Art Deco more than a passing interest for you? What about it speaks so strongly to you as a person and a passionate heritage advocate?

Ivan Man Dy: I grew up in Manila, so Art Deco was always around me. When I was in university, I joined like-minded folks picketing the demolition of the iconic Jai Alai Building along Taft Avenue in 1999. That moment was my awakening, the start of my involvement in heritage conservation.

My interest in Art Deco waxed and waned over the years until I had the chance to present at the 2015 World Art Deco Congress in Shanghai. That’s when it hit me: there was a far-reaching global interest in this design movement.

I also noticed how underappreciated Art Deco was locally, which led to its poor representation. I felt compelled to take action. That’s when I decided to pursue the topic seriously, setting up Art Deco Philippines to share and spread the story of Pinoy Art Deco to the international community, while doing intensive research and documentation on it.

Art Deco resonates with me because it originates from a period in history that fascinates me — the 20th century, up to World War II. I’ve always been drawn to urban histories and how Art Deco transcended various design fields, including architecture, industrial design, fashion, and graphics, all intertwined with the socio-political, economic, and cultural histories of the time. Just the stuff to geek about!

Between 1925 and 1950, Art Deco left Paris for the world and took deep roots in our sunny shores. What social or economic conditions allowed the movement to flourish in the Philippines, and how did we make it distinctly our own?

Many factors came into play. Under American colonial rule, Filipinos were granted scholarships to study in U.S. universities. These Western-educated Filipinos came home with modern ideas and introduced the Art Deco style.

Economic conditions also played a role. Free trade opened the doors to American cultural products, ranging from language, film, literature, and transportation to technology, all of which carried the Art Deco design vocabulary. Manila became the center of Art Deco expression in the Philippines, and the style eventually spread to regional cities.

Philippine Art Deco shares the same recognizable elements: zigzags, speed lines, stylized reliefs, ziggurats, but our interpretation is less flamboyant than the high Art Deco buildings of cities like New York or Chicago. The difference also lies in materials and scale. More developed cities had the economies to build grander structures, while ours were smaller, often boutique-sized.

Philippine Art Deco also drew from local cultural elements, making it distinct. Discovering both the similarities and variations in interpretation from one country to another —that’s what gets Art Deco junkies like me excited!

This exhibition gathers nearly 300 objects from Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. How did you build the curatorial framework for selecting and sourcing these works? What were your hardest calls: what to include, what to leave out?

This exhibition is timed for 2025, marking the worldwide commemoration of the Art Deco centennial. The items were selected based on documentation first presented in the book “Deco Filipino: Art Deco Heritage in the Philippines” by Ivan Man Dy and Gerard Lico (2020, ArtPostAsia). We also drew from other sources, like museums, private collections, and institutional archives.

The goal was to tell the story of Art Deco’s many expressions: in architecture, industrial design, graphics, and fashion, and how it entered the daily lives of Filipinos at that point in history. Art Deco’s influence extended beyond buildings; it also appeared in everyday, utilitarian objects, such as furniture and writing instruments.

Not all items are locally made. We included select foreign pieces to showcase the breadth of Art Deco design worldwide. We did our utmost to select the best examples in each category, but there were limitations, as most came from private collections. Many of these items are being shown publicly for the first time.

We also brought in pieces from the National Museum’s own art collection and from other institutions, recontextualizing them for the exhibit. Unfortunately, some outstanding works had to be left out due to logistical challenges.

Your show brings together architecture, furniture, fashion, and everyday design, all bound by a single style. Can you walk us through how the show is structured? How do you suggest visitors approach the galleries to get a well-rounded sense of Philippine Art Deco?

The exhibit spans two galleries in the Fine Arts Building. Gallery X presents the history and arrival of Art Deco within a socio-historical and cultural context, focusing on its architectural expressions —the aspect most people associate with the style.

Gallery VII showcases Art Deco in daily life, illustrating how it permeated everyday objects such as furniture and industrial products, making them accessible to a specific social class. This gallery demonstrates the breadth of Art Deco’s application beyond architecture.

The layout, design, and placement of items were curated by our team in collaboration with Caramel Creative Consultancy, led by my co-curator Miguel Rosales.

This is also the largest single exhibition the museum has ever mounted. Why do you think the institution committed so deeply to this subject? What was it like collaborating with the National Museum team on a project of this size?

The National Museum recognized the significance of this project. Art Deco had only a quarter-century span in Philippine design history, yet it produced many firsts and masterpieces in architecture. Many people associated with this style later became National Artists, and still, there had never been a comprehensive exhibit on the subject. Mounting it this year felt very timely; besides, 100 years is something to celebrate, right?

Working with the National Museum on this project was both an honor and an advantage, given the institution’s stature. Of course, there were challenges and procedural bureaucracy, but I am deeply grateful to the Architectural Division team, who supported us until the very end. We worked within the means (and limits) available to mount such a ground-breaking exhibit.

Curating your first major museum show surely comes with lessons. What surprised you most about translating scholarship and advocacy into a physical exhibition? What about our Art Deco heritage do you most want Filipinos to appreciate beyond its visual appeal?

Mounting an exhibit of this scale involves so many moving parts! Truly endless! Documenting the pieces is one thing, but handling the logistics on a regional, inter-provincial scale requires navigating numerous legal, technical, and organizational challenges.

I was surprised and grateful for how generously some people loaned family pieces, including not just small items but also large furniture. It really took an entire country to bring this exhibit together.

Above all, I hope people gain a deeper appreciation of Art Deco not just for its aesthetic qualities, but for how it intersects with the historical, socio-political, cultural, and economic aspects of Philippine modern heritage in the 20th century.

My congratulations, Ivan, on a splendid show! •

Edited release on the exhibition from the National Museum of Fine Arts

Art Deco: Modernity and Design in the Philippines, 1925–1950 marks the centennial of the style first introduced in Paris. Curated by Ivan Man Dy and Miguel Rosales with the Architectural Arts and Built Heritage Division, the exhibition explores how Art Deco shaped Philippine life across architecture, furniture, fashion, film, and graphic design.

Among the museum’s largest single shows, it features over 300 pieces gathered from more than 40 lenders nationwide, underscoring the breadth of Art Deco’s influence on Filipino design and modernity. The objects are grouped across two galleries.

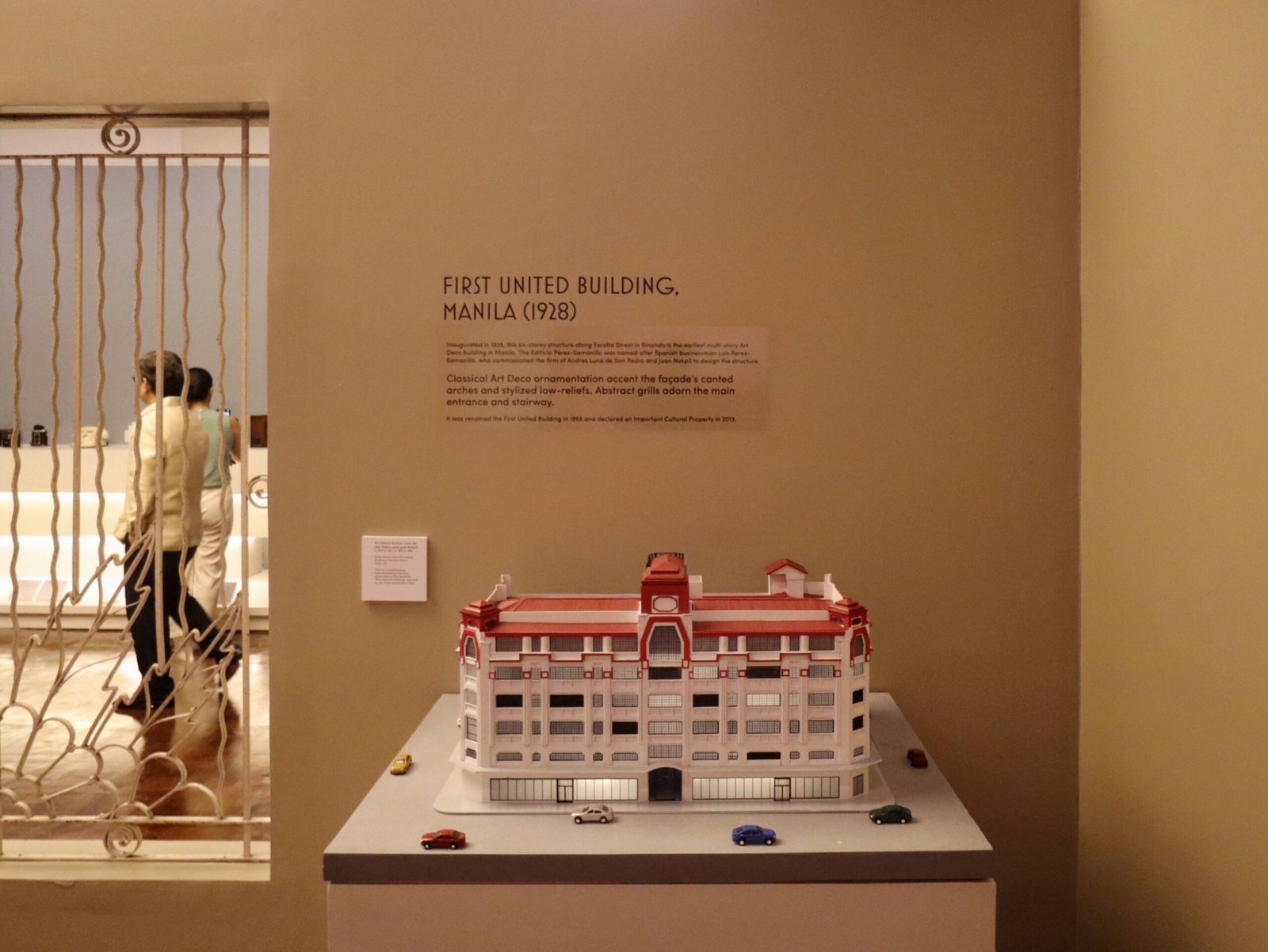

Visitors begin at Gallery X, which traces the movement’s origins at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris and its arrival in the Philippines during the American Colonial Era, with architecture taking center stage. Landmark structures, such as the Metropolitan Theater, the Generoso Villanueva Mansion, and the Misamis Oriental Provincial Capitol, are rendered in scale models. True-to-life casts of Severino Fabie’s bas reliefs for the former Capitol Theater in Escolta greet visitors at the entrance, alongside salvaged architectural fragments. Paintings and illustrations by Fabian dela Rosa, Antonio Dumlao, Pablo Amorsolo, and Dominador Castañeda highlight Art Deco’s imprint on Philippine visual arts from the 1920s to 1950.

Gallery VII presents a lesser-known dimension of the movement, featuring jewelry, graphic design, fashion ephemera, and prized furniture from private collections across Metro Manila, Quezon, Pampanga, Negros Occidental, and beyond. Original 1930s ternos worn by Maria Agoncillo Aguinaldo and Doña Aurora Quezon are on display, alongside intricate bureaus, dressers, beauty implements, and industrial objects such as radios and writing paraphernalia, many of which are being exhibited publicly for the first time.

A year in the making, the exhibition presents a distinctly Filipino lens on a global design movement still celebrated a century on.

Art Deco: Modernity and Design in the Philippines 1925-1950 at the National Museum of the Philippines – Fine Arts runs from November 27, 2025, to May 31, 2026. The museum is open daily from 9AM to 6PM. Entrance is free.