Words and images WTA Architecture and Design Studio

Interview and editing The Kanto team

Tagaytay City Hall

Tagaytay City Hall by WTA Architecture and Design Studio

Shortlisted under Completed Buildings, Civic and Community Category, WAF 2025

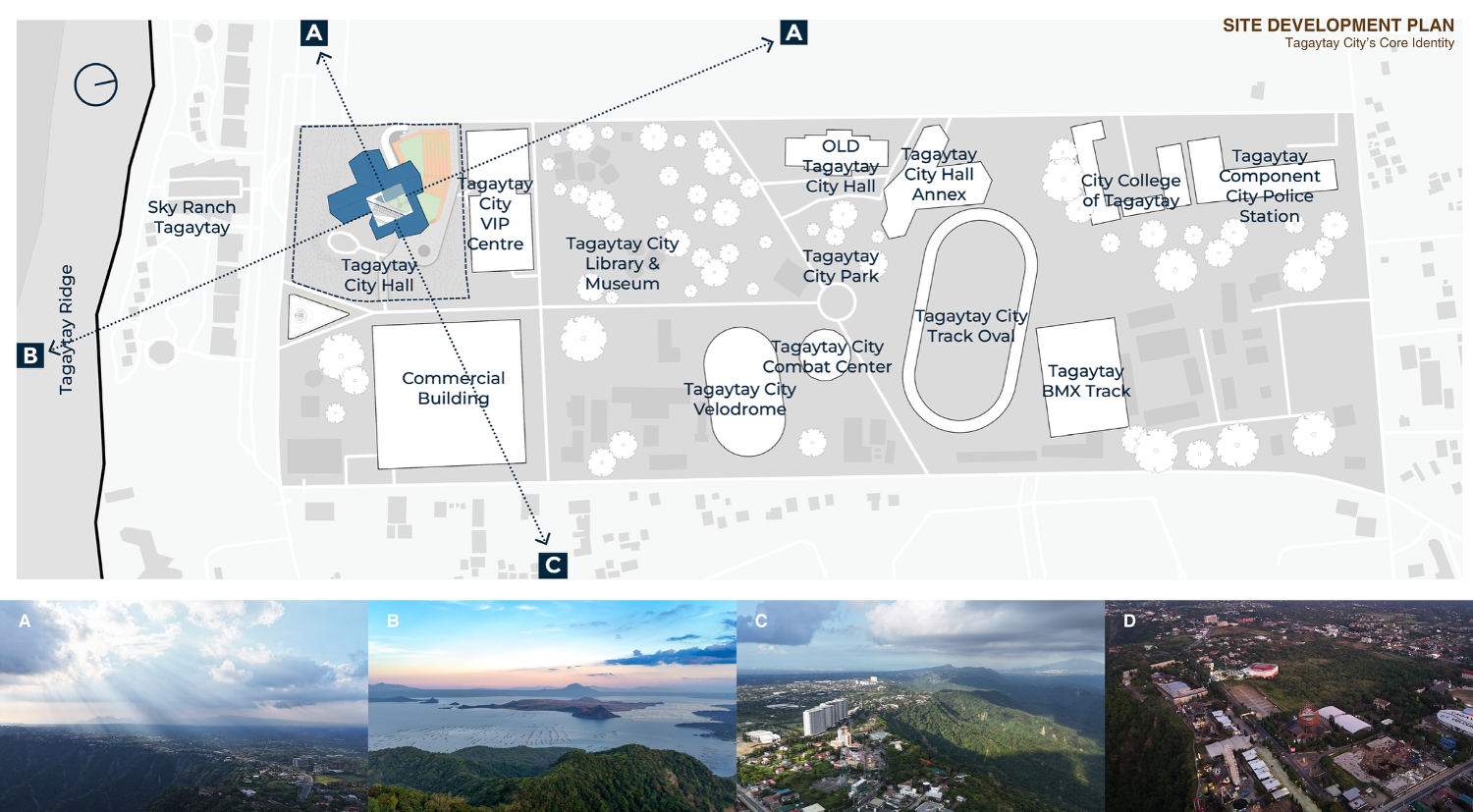

Lying along Taal Ridge on the northern edge of the Taal Caldera overlooking Taal Lake, Tagaytay derives its name from the Tagalog word for mountain ridges and is a popular tourist destination known for its cooler climate and forested slopes. The city’s identity has always been shaped by Geography, Forests, and Tourism.

Geography gives Tagaytay its much sought-after location with its cooler climate and a culture that celebrates edges and boundaries. The cooler climate also allows for one of the few places near Manila that is dominated by pine forests. These forests create unique vertical silhouettes and serve as sanctuaries for revolutionaries during the Philippine Revolution of 1896. Modern Tagaytay’s identity is inextricably tied to tourism and the more than one million visitors who visit this city each year and more than double its local population of 85,000, creating a vibrant culture of social exchanges.

The Tagaytay City Hall embraces these three influences to help define the cultural identity of Tagaytay that often gets swept away by the rapid commercialization and development brought about by tourism.

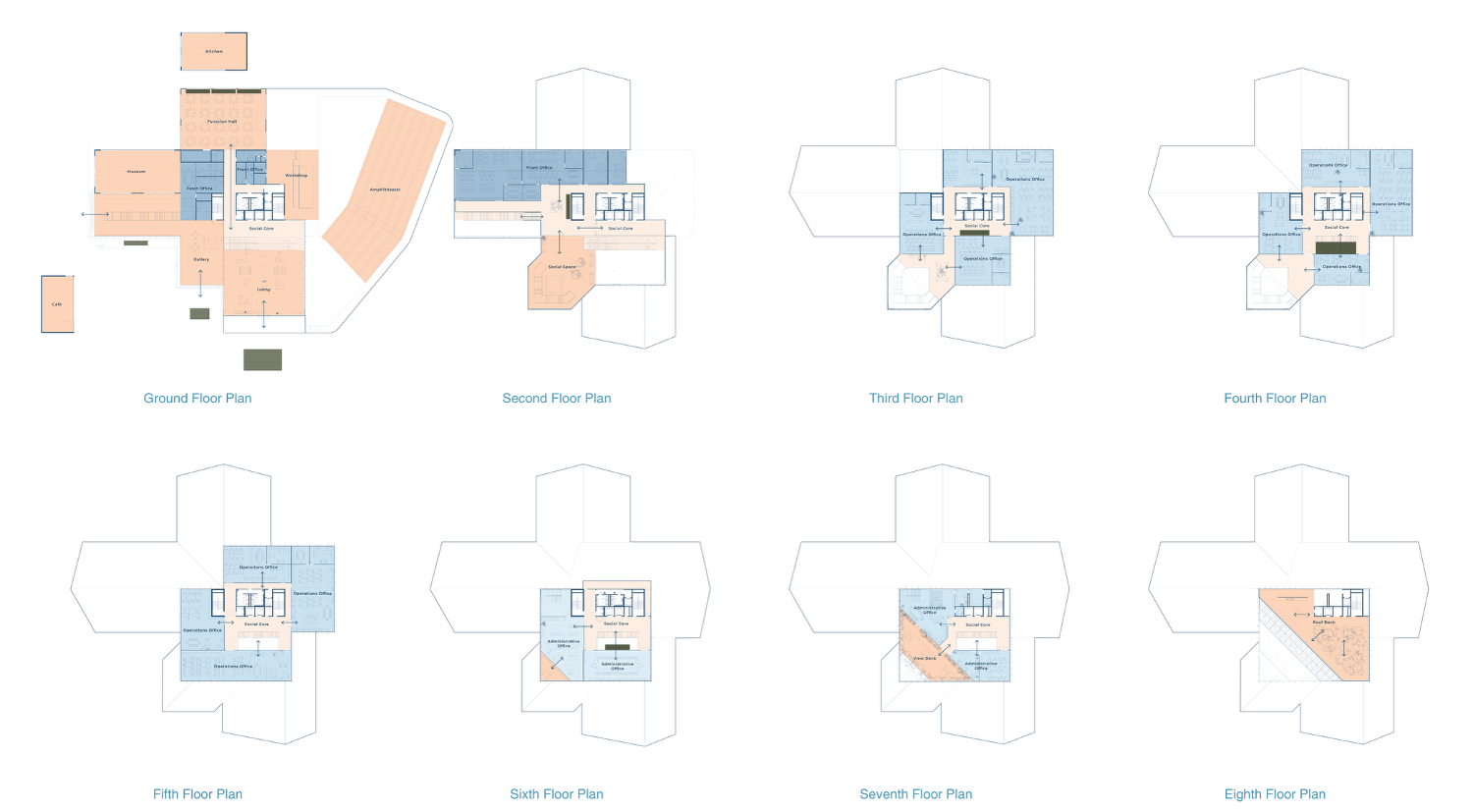

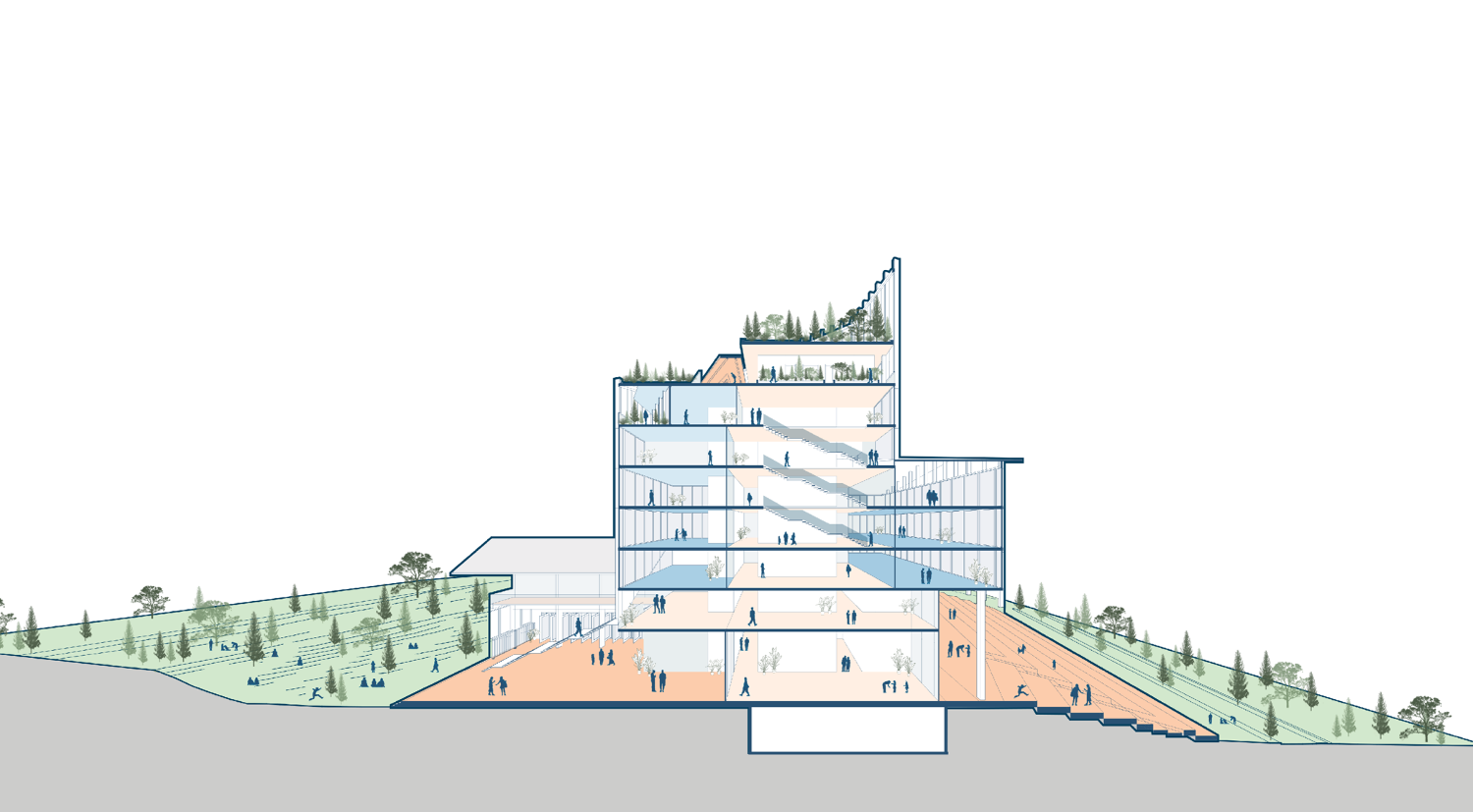

The city hall is a layered extrusion of public and administrative spaces topped by an emphasized edge in a diamond form—an architectural ridge—diagonally cut as a geometric symbol of the caldera. Where nature begins in raw, unstructured form, architecture imposes order, not to dominate, but to celebrate. This principle guided the spatial planning: from open civic terraces to layered public parks.

The city hall embraces its purpose and the city’s role as an escape from the metropolis. From government officials to residents and visiting tourists, the architecture reflects shared spatial identity. The result is an open, accessible civic forum that champions transparency in governance, both symbolically and functionally, with its public halls and axial views. The central open-core design allows for visibility and natural surveillance, fostering trust, productivity, and communal interaction. More than a government building, it becomes a democratic space—formed through shared purpose and lived in by the community.

Drawing from the vertical silhouettes of the surrounding pine forests, a vertical rhythm that echoes these natural forms shrouds the city hall. This takes shape in the soft progression of vertical golden-brown fins across the façade, which terminate in an irregular and organic edge that extends up to the skyline. The design fosters a visual familiarity, bridging nature with community, creating a familiar and beloved civic presence.

The new Tagaytay City Hall is not just a functional government office—it is a silhouette of identity, capturing a city’s soul through its architecture.

Welcome back to WAF, WTA! The design of one of your entries, Tagaytay City Hall, deftly draws on local metaphors; can you educate us on the decision to consolidate programming into one tall volume instead of multiple lower ones? Given public criticism of high-rises along the Tagaytay ridge, was the building’s height ever an issue, and if so, how did you address it?

WTA Architecture and Design: Thank you, Kanto! Grateful for the chance to share this project with your readers. For the Tagaytay City Hall’s programming, we configured it in such a way that the main building houses departments with low to medium foot traffic, including Technical, Administrative, Accounting, and Executive offices, while a smaller Annex Building accommodates offices with heavier daily transactions.

Five factors guided the decision to consolidate the program vertically: programmatic connectivity, social core, compact footprint, nature’s vantage, and security and efficiency. We clustered departments that work closely together on the same floor to ensure efficient coordination, also creating vertical adjacency between related clusters to promote seamless interaction.

A central vertical core connects all levels through a series of open, shared spaces, from a library to a gallery, fostering accessibility, transparency, and community. By limiting the building’s footprint, we were able to return more of the ground plane to the public as open, civic space.

The tower itself offers a rare perspective of Tagaytay, from its barangays and ridges to its iconic view of Taal, celebrating the city’s natural beauty. We also found that a smaller footprint allows for easier site control and more efficient building management.

On your question about building height, this was never an issue for the site. The city strictly enforces a 5-meter height limit along ridge-side properties, but the city hall stands in a different zone where the tower form complies with local regulations.

How did you reconcile the city hall’s footprint with the surrounding pine forests? What are the sustainability measures employed that move the design beyond symbolism to delivering real ecological impact?

WTA: The site previously held the old Tagaytay Convention Center, already surrounded by pine trees. During demolition, rubble from the site was reused as fill for the adjacent Sigtuna VIP Convention Center extension. Since our footprint is smaller than the original convention center, no pine trees were cut or relocated.

We employed key sustainability strategies for the structure. Passive cooling was made possible through the open social core. Given Tagaytay’s mild climate, all shared spaces in the social core are naturally ventilated and without mechanical air-conditioning. Operable windows in select offices allow natural ventilation.

For energy efficiency, air-conditioning systems have fresh air intake features to reduce cooling loads. The open atrium and activity-filled core promote stair use and physical interaction across floors to encourage vertical movement. The main building also currently operates a rainwater collection and recycling system. A larger, integrated water recycling facility for the entire complex is planned in the future.

“We designed a spatial layout that promotes transparency and accessibility, ensuring the building reflects the government’s responsibility to its people.”

Beyond being a government center, how does the city hall’s design invite both residents and visitors to engage with Tagaytay’s natural and civic identity?

WTA: Beyond serving as a city hall, this project was envisioned as a public place for the people. It offers a café, pasalubong center, amphitheater, museum, gallery, art and sculpture park, and several viewing decks, all open even beyond office hours. These spaces feature works by local artists, furniture crafted by Tagaytay woodworkers, and architectural details shaped by local craftsmen, reflecting a shared sense of pride and belonging.

This is WTA’s 13th WAF shortlist since 2015, making you the most shortlisted Philippine practice. What keeps you returning year after year?

WTA: For us, the purpose of joining WAF has always been sharing our stories and creating a sense of pride for Filipinos around the world.

Of course, the learning never stops. WAF allows us to study and engage with the best projects and practices globally. Each year, we come home inspired to evolve our architecture further.

Around the world, public faith in governments is under strain. What do your civic projects say about working with government, and how can architects help ensure the public gets the spaces it deserves?

WTA: We see two perspectives here. The first is in building the project itself, through a collaborative and accountable process among the LGU, our contractor, and our studio. It was a truly barrier-free partnership where everyone shared ownership of the goal.

The second is in the long-term operation of the City Hall. Together with the department heads and the executive office, we designed a spatial layout that promotes transparency and accessibility, ensuring the building reflects the government’s responsibility to its people. •