Words Joshua Alexander Manalo

Images Joshua Alexander Manalo and Patrick Kasingsing (Philippine Pavilion)

The Venetian Arsenale, the venue of this year’s Philippine Pavilion for the Venice Art Biennale, is a physical reminder of the floating city’s ability to adapt. The Arsenale was once a medieval shipyard founded in the early 12th century (some historians even label it the “world’s first factory”) when the then Republic of Venice was the world’s greatest naval and trading superpower. It has undergone an artistic metamorphosis in the 21st century as, since the 1980s, it has served as one of two main venues (the other being the Giardini) for the La Biennale Arte de Venezia, contemporary art’s most prestigious art exhibition.

Few cities in the world can match Venice’s cultural influence. However, as the city shifted from a naval and trading powerhouse to a popular tourist destination, it further transformed from being one of Europe’s most prominent Renaissance capitals into a tired repository of artifacts. Today, it is a sinking city struggling with over-tourism and the effects of climate change. Venice must bear such burden and responsibility, particularly when organizing the Venice Biennale.

The art world tends to be an isolated bubble, an idealized utopia. But it is not just all about being in a liberal, anti-discriminatory, non-profit, classless La La Land. Nowhere is this more apparent than during the vernissage of an event such as the Venice Biennale, which I had the opportunity to attend. Almost half of the 86 national pavilions are European countries—about twenty hail from Asia, with just 12 nations from Africa. To refresh our aging 20th-century memory, let’s not forget that Hitler and Mussolini met for the first time and exchanged Fascist greetings at the Venice Biennale of 1934. The artist of the current Israeli Pavilion has refused participation due to the current geopolitical conflict. The Biennale is inherently political, for better or worse.

These complexities notwithstanding, it is still noteworthy for the Philippines to find representation in such a global event, with a national ‘pavilion.’ Even the concept of having a “national pavilion” is a fertile source of discussion to challenge and complicate the idea of what it means to be from another place, a load that this year’s Philippine Pavilion team embraced wholeheartedly. It is a task that all national pavilions had to bear for this year’s Biennale, which carries the theme of “Foreigners Everywhere/Straniero Ovunque,” helmed by Brazilian curator Adriano Pedrosa. The Biennale’s 60th edition is noteworthy for having its first curator from the Southern Hemisphere and featuring more than 300 artists and artistic groups, mainly from the global south and first-timers, to the Biennale. It poses a timely query: who are the foreigners?

The official title of this year’s Philippine Pavilion is: “Sa kabila ng tabing lamang sa panahong ito/Waiting just behind the curtain of this age,” featuring the works of Mark Salvatus curated by Carlos Quijon, Jr. It is an experiential work of which sound is a crucial component—hissing, dissonant, post-apocalyptic, rainforest sounds resonate throughout the pavilion while sheer curtains seem to hover all around like thick fog around the two most noticeable visual components of the work—a video projection and brass instruments perched on top of fiberglass meteor-looking objects (some of which were conveniently used as seats for Biennale viewers). The work inspired in me renewed reverence for our nation’s intangible heritage—music, philosophies, and folk traditions passed on orally, and it is this that the work conveys eerily and prophetically.

Mt. Banahaw is undoubtedly the star of the show. It is an active volcano in Lucban, Quezon, said to possess healing energy from its hot springs. Its thick forest cover has shrouded centuries of rebels and revolutionaries, and its enduring mystique has been associated with unexplained occurrences like UFO sightings. Visuals of the mountain take center stage in the video projection, as do the communities, flora, fauna, and even the strange UFO dances that have sprung from it.

This work is a beautiful reminder of how nature can inspire us and tell stories through our relationships with each other. Our traditions and heritage are born from our connections to the natural world, which can be mysterious, unknown, and inspiring. Mark Salvatus may be seen as a prophetic figure in the line of lay preacher turned revolutionary Hermano Puli, anchoring our dreams of the future with a sense of continuity.

The Philippine Pavilion has created a great monument to the enduring spirit of Banahaw. Monuments serve as fixed points that allow us to orient ourselves and define the emotional psyche of a people. They become a physical record of history. When we build monuments like this, we are reminded that it’s essential to consider what components we need to “build up” and how long we can continue to do so. When something goes up, an entire infrastructure supports it.

The exhibition is an honest attempt to explore and challenge the idea of social constructs and nature from a fresh viewpoint. By patiently observing how these social constructs evolve in tandem with nature, over time, narratives can form. A new visual folklore is being created.

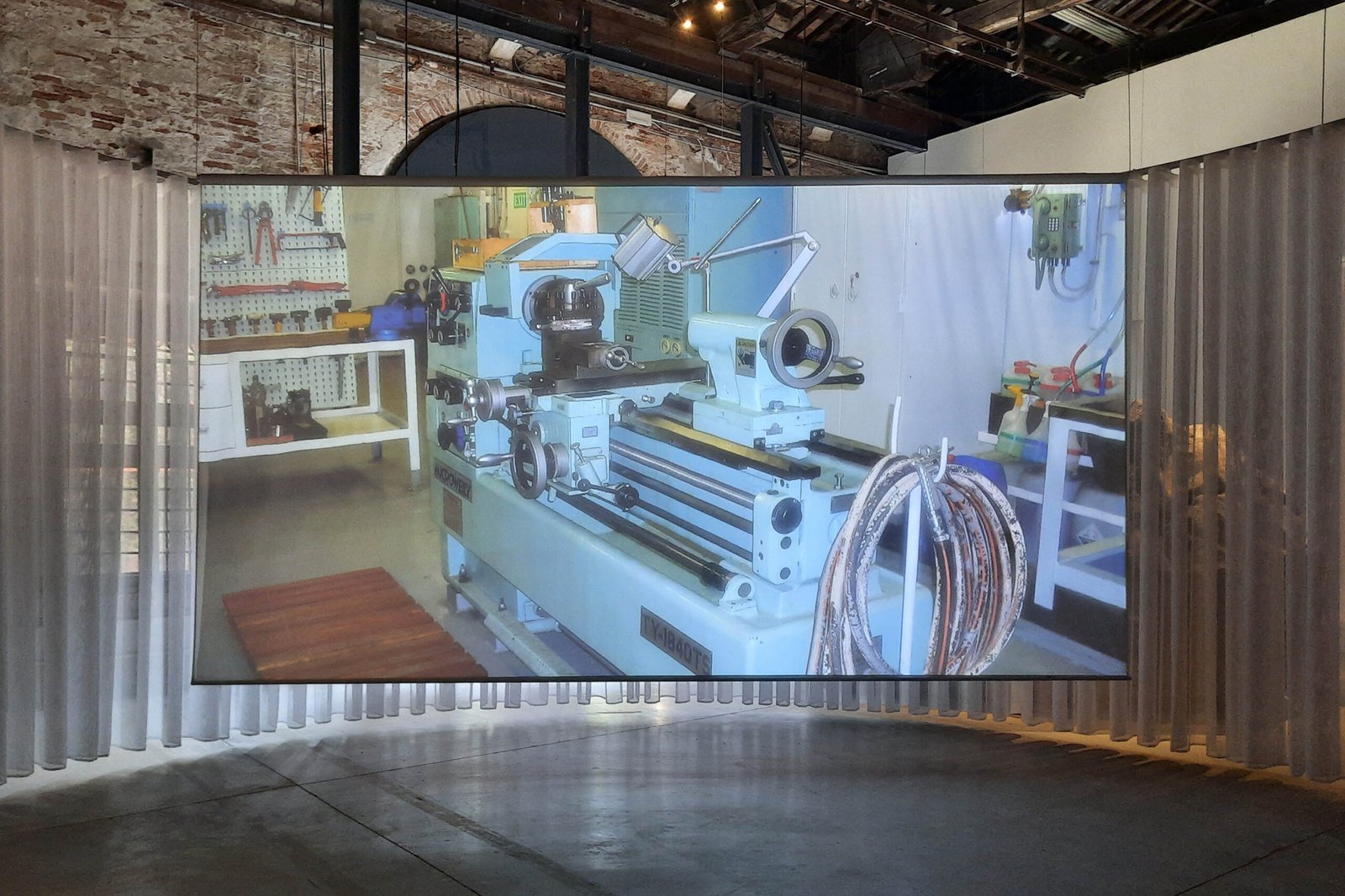

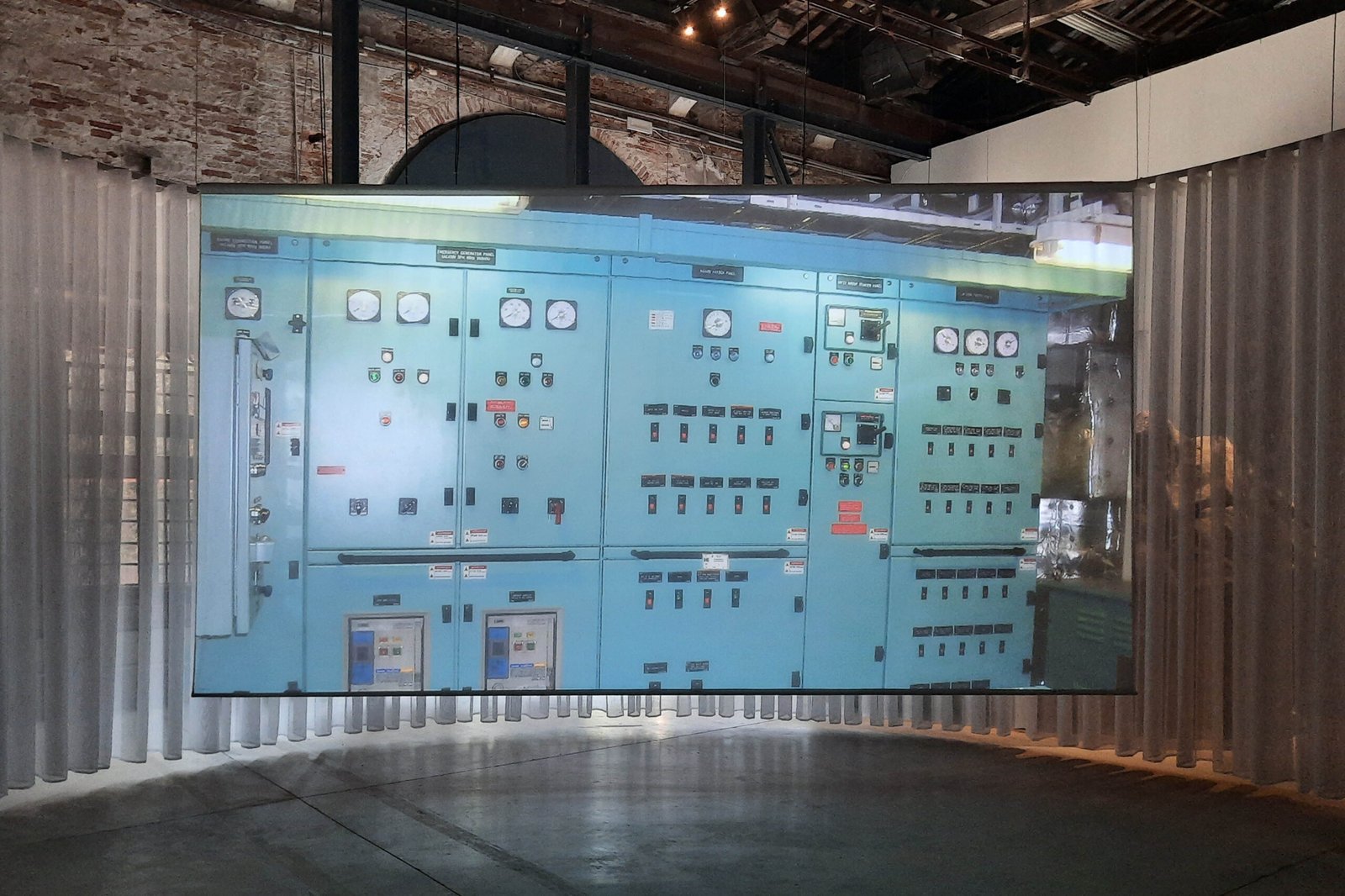

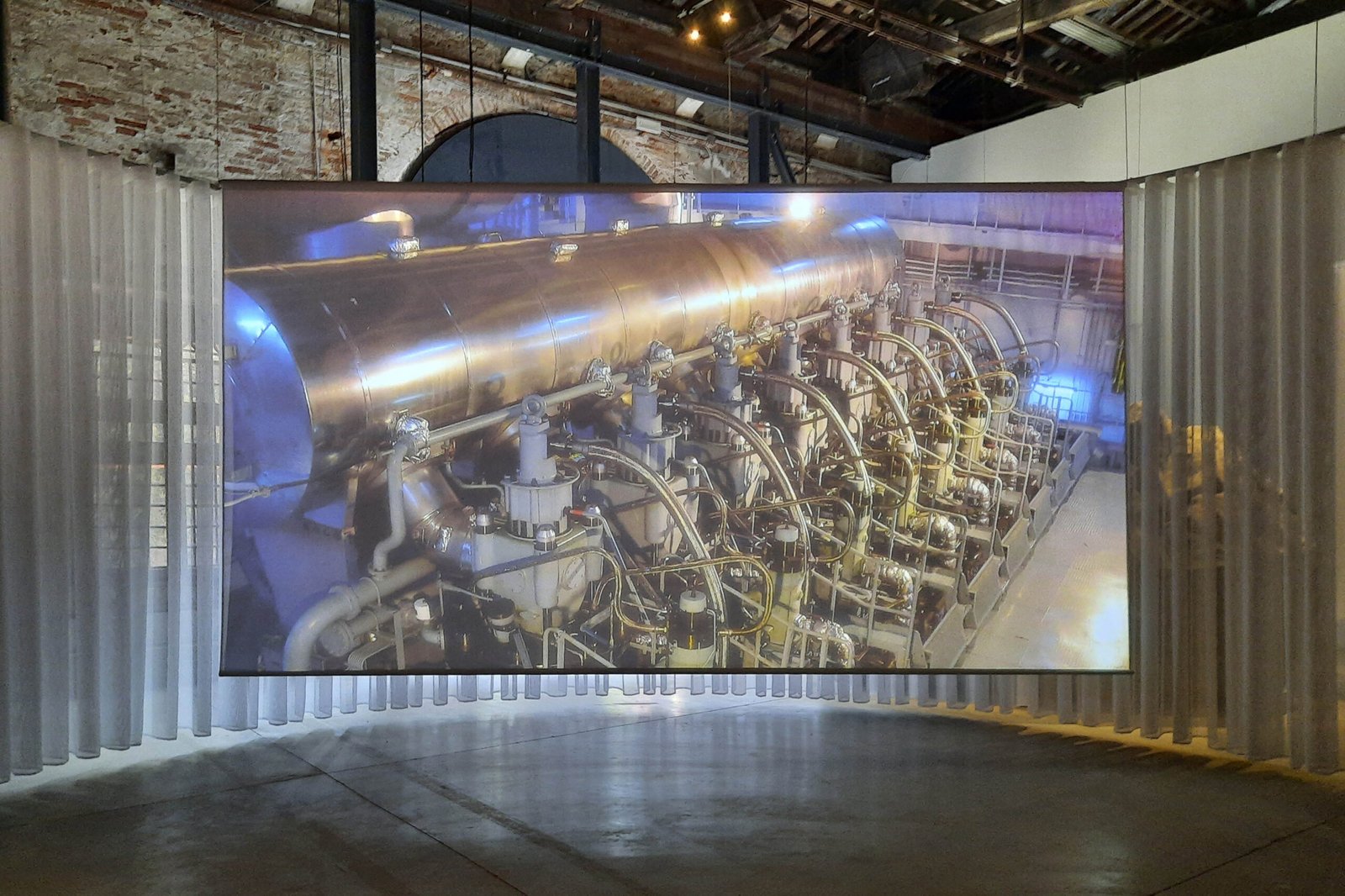

This is seen in the video channel component of the work, which I helped coordinate with the Manila-based maritime company PHILCAMSAT, which runs ship simulation technology and facilities for training seafarers. They generously allowed the artist full use of these facilities, thereby providing crucial visual content for the artist—an imagined link to the artist’s hometown of Lucban, where Banahaw looms over.

A significant population of seafarers calls Lucban home, and the artist himself can attest to this as some of his close family members are seafarers—something commonplace when talking about the Filipino diaspora but still relevant as ever. On the one hand, the ship simulation proved a brilliant source of visuals that the artist utilized to communicate the complexity of migration and employment. On the other hand, it is a sober reminder that the struggle for survival in the global workforce and honing skills for excellence in the maritime sector is unending. This utilization of maritime technology in the work couldn’t have been more apt for a global art show held in a former maritime republic, one with a love-hate relationship with water. Through this work, a new shared narrative and emotional connection is presented to us to make sense of a chaotic universe. It explores the foreign world through a distinctly Filipino lens yet with a universal aspect. We see the ‘foreign’ pervade in the mysterious hissing in a verdant mountain forest, the unknown that awaits at the end of a revolution, or the untold secrets that lay beyond and beneath the ocean waves. This shared anxiety and anticipation for the unknown connects us all within a planet in flux; we realize that there are foreigners everywhere but also nowhere. •

The Philippine Pavilion will be open from April 20 to November 24, 2024 at the Arsenale in Venice, Italy.

Joshua Alexander “Joey” Manalo is a classically trained pianist, having navigated through scores on his own from the age of six, eventually taking private lessons and graduating cum laude in 2009 at Rutgers University with a Minor in Music and a Major in Psychology. In 2013, he completed his Masters in Global Entertainment and Music Business at The Berklee College of Music, Valencia Campus. Joey has performed in various master classes and venues, such as the Cultural Center of the Philippines, Philam Life Theater, Manila International Piano Festival, Fondation Bell’Arte Paris, Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, and Wiener Musikseminar. Joey currently manages Outlooke Pointe Foundation’s projects and art collection. The non-profit organization was founded by his father, Jesulito Manalo, in 2007 in a bid to support emerging artists and foster creative collaborations “with the vision of utilizing art as a tool for nation-building.”

One Response

I am impressed at the depth of your immersion into the subject matter. Your language is also superb! Glad to read this and proud of the Filipino artists and Philcomsat for bringing the new Filipino forward in the planet’s search for a new identity.