Interview and introduction Patrick Kasingsing

Editing Lawrence Carlos

Images M+, Hong Kong, with photography by Patrick Kasingsing

A re-introduction to Mr. Pei

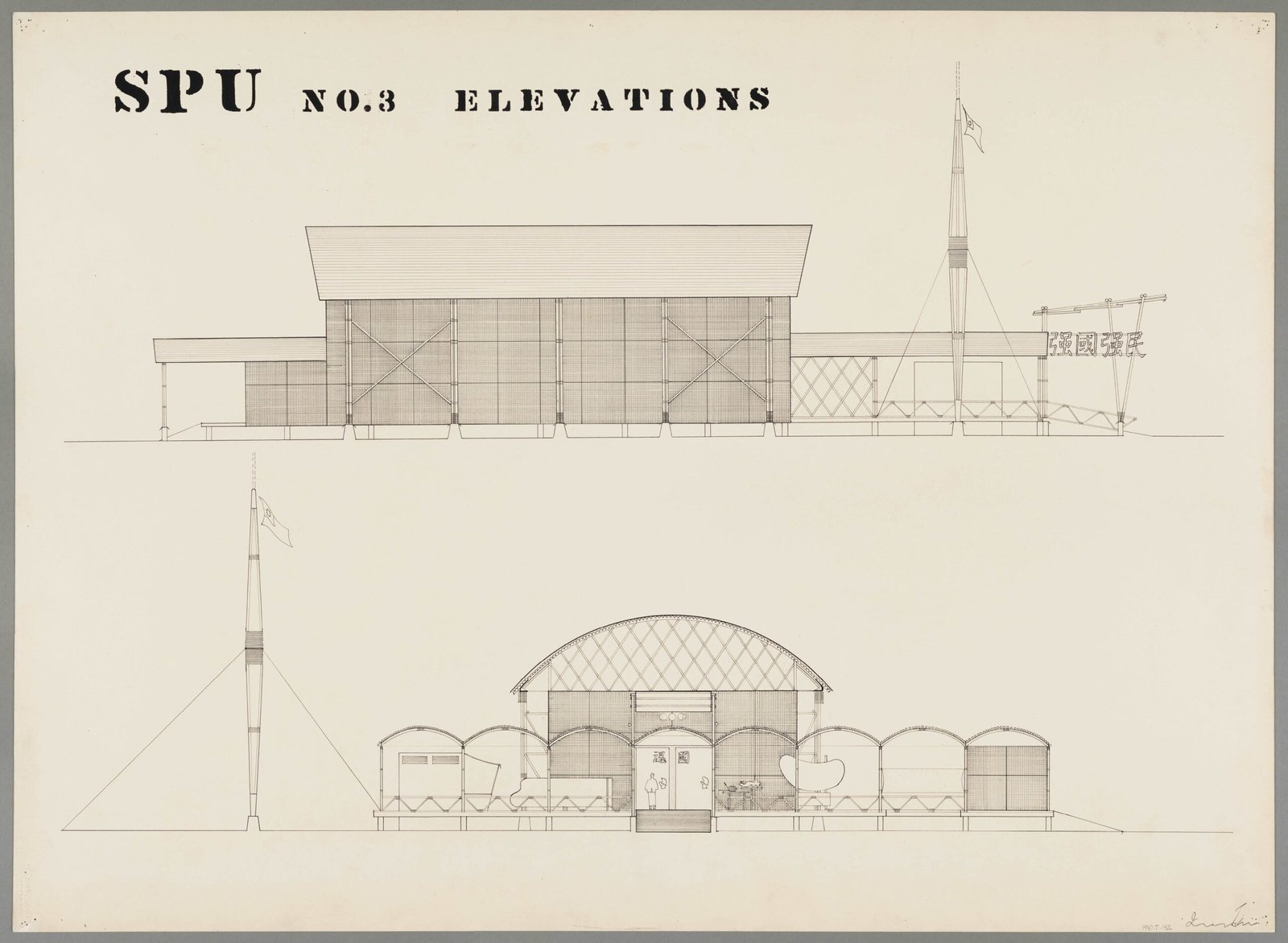

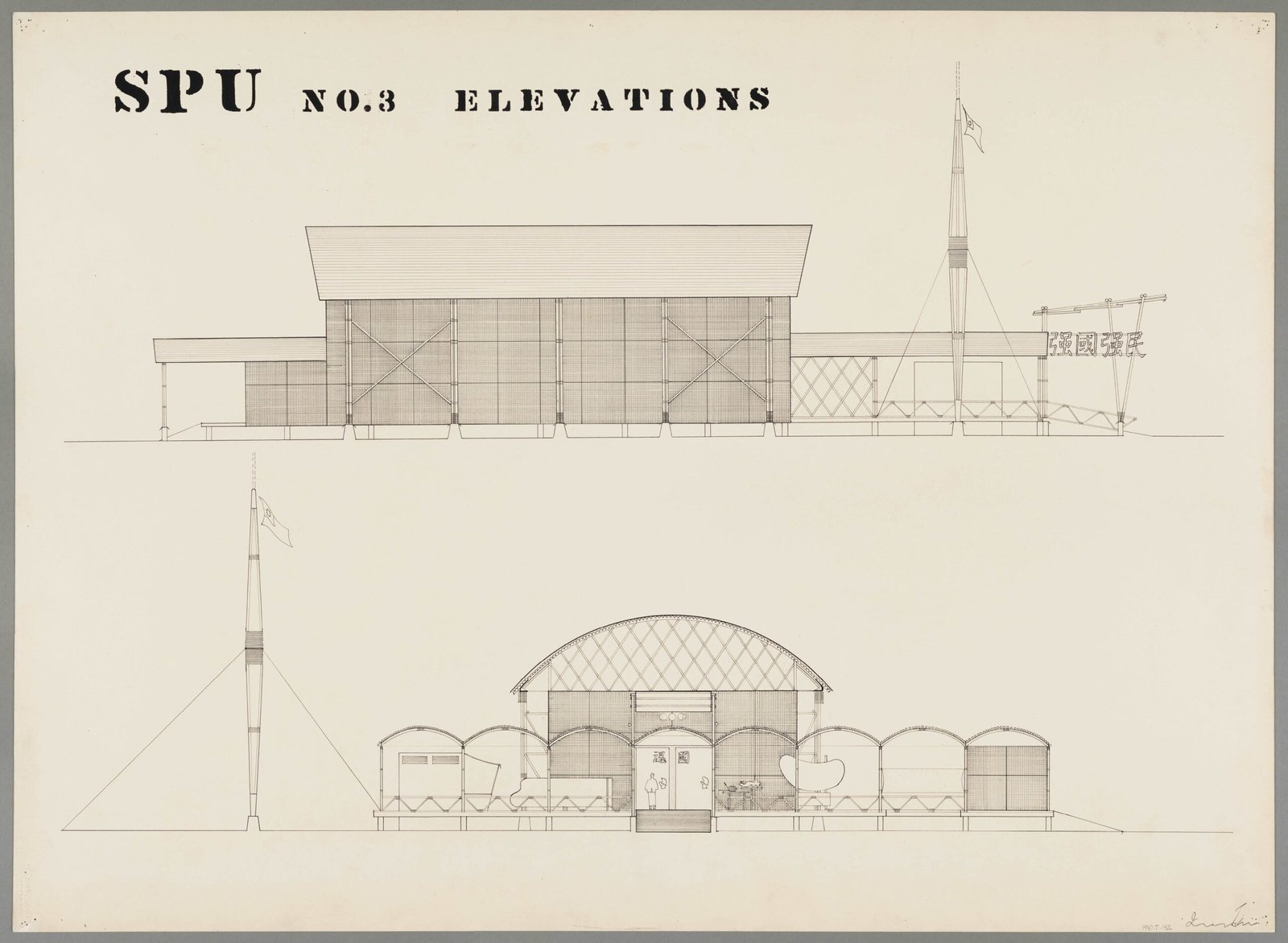

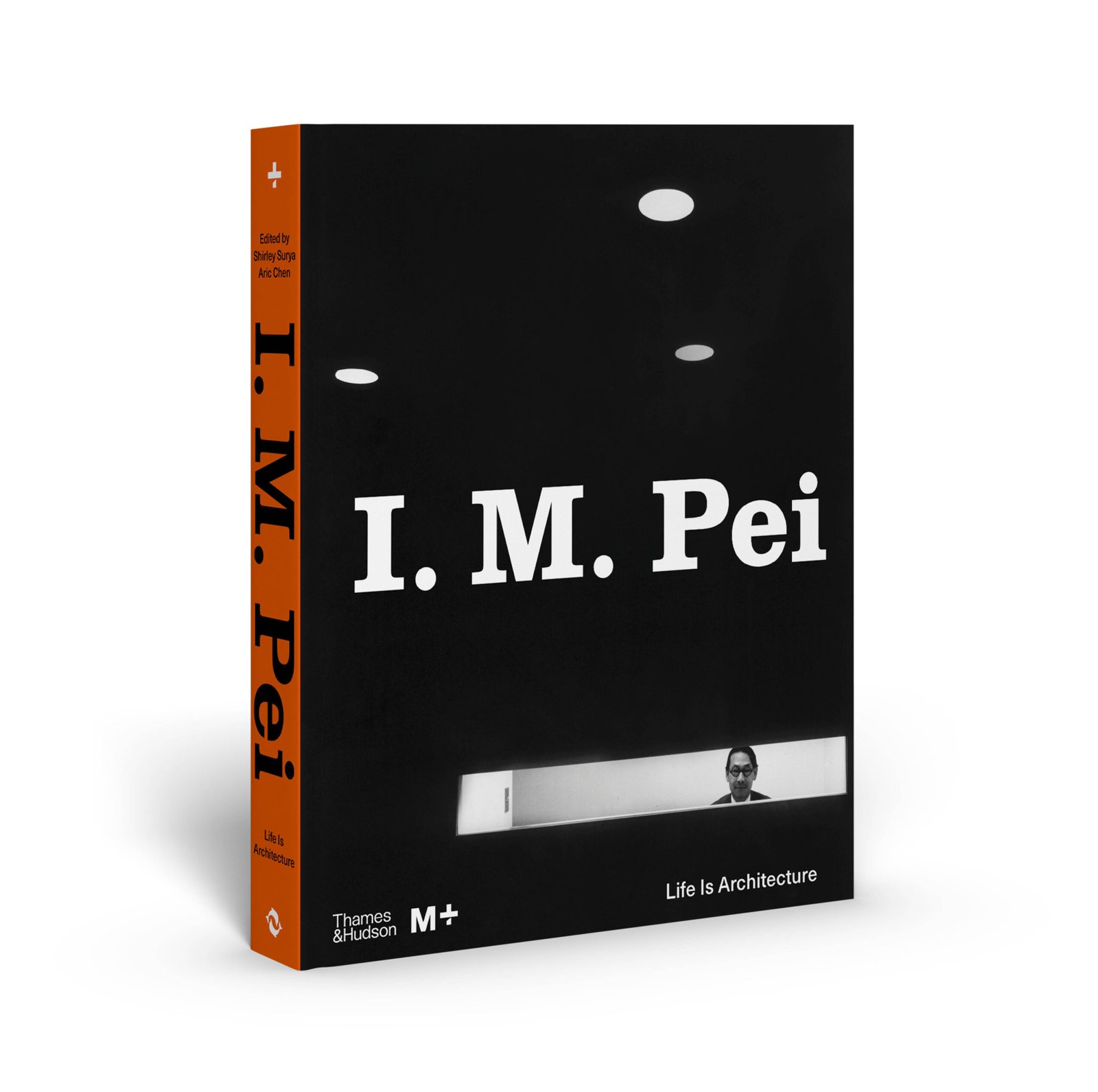

One project in I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture, the landmark retrospective on Pritzker laureate Ieoh Ming Pei (I. M. Pei) at Hong Kong’s M+, left an indelible impression.

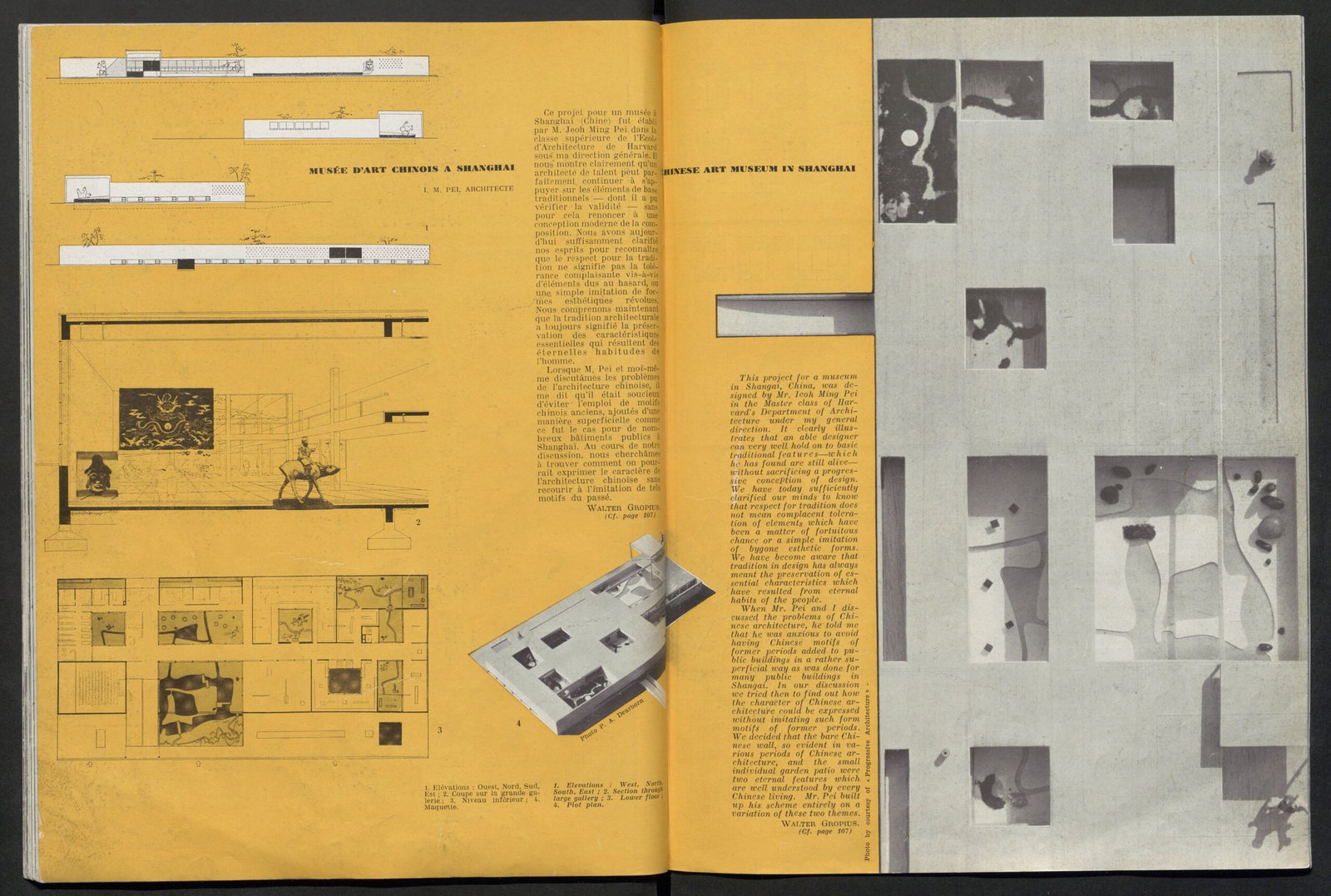

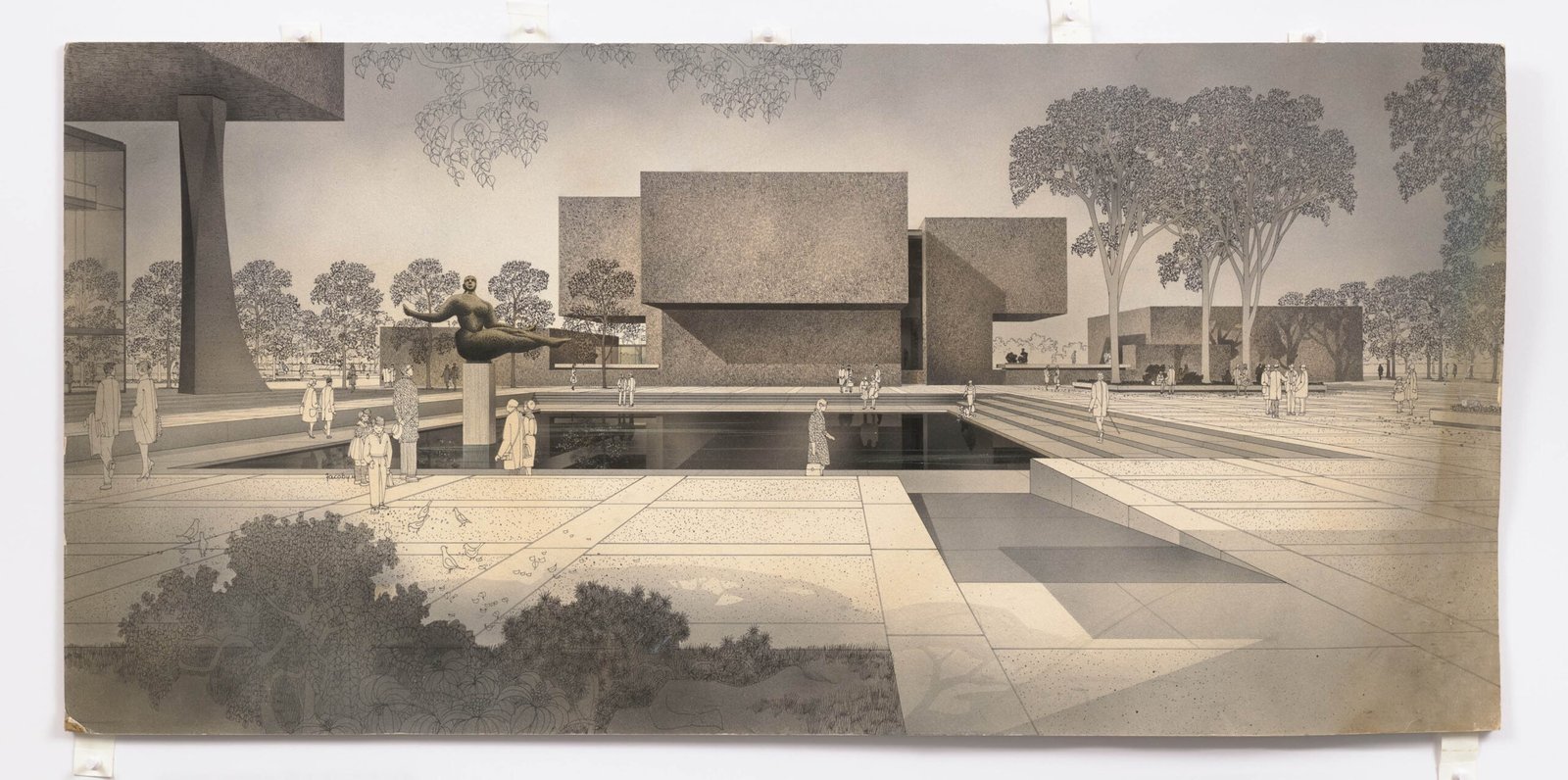

It was a work I was unfamiliar with prior to the exhibition, an unbuilt design rendered in a pristine white maquette: Pei’s 1946 thesis for his Master of Architecture at Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD). His Museum of Chinese Art for Shanghai was starkly modern yet deeply rooted in cultural and historical sensibilities, with landscapes recalling traditional Chinese gardens and the asymmetrical elegance of Chinese architecture. This design, described by Barry Bergdoll, Meyer Schapiro Professor of Art History at Columbia University, as “a museum space that was as much community center as a museum,” is a testament to Pei’s genius: a balance of innovation and cultural respect within a design that is both responsive and attuned to human interaction.

Even with my background as an architecture journalist, the exhibition was overwhelming in its visual richness. Spanning 1,600 square meters, it invites viewers to explore Pei’s life through detailed models, lush imagery, intricate sketches, and rare archival footage. With over 300 objects gathered over seven years of research, the exhibition unfolds in six chapters: ‘Pei’s Cross-Cultural Foundations,’ ‘Real Estate and Urban Redevelopment,’ ‘Art and Civic Form,’ ‘Power, Politics, and Patronage,’ ‘Material and Structural Innovation,’ and ‘Reinterpreting History through Design.’ It’s accessible and engaging for the public while offering substantial insight for architects and scholars alike.

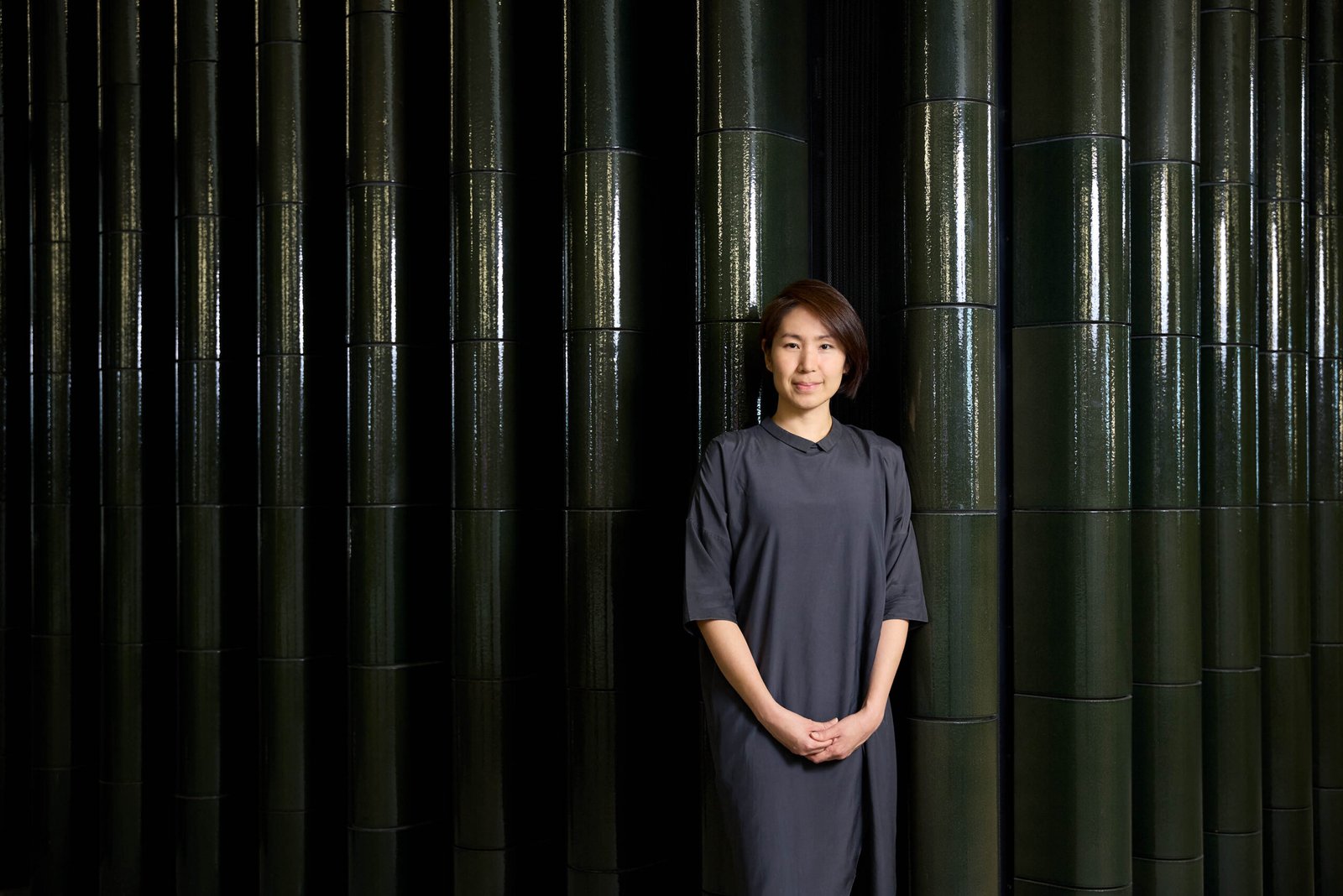

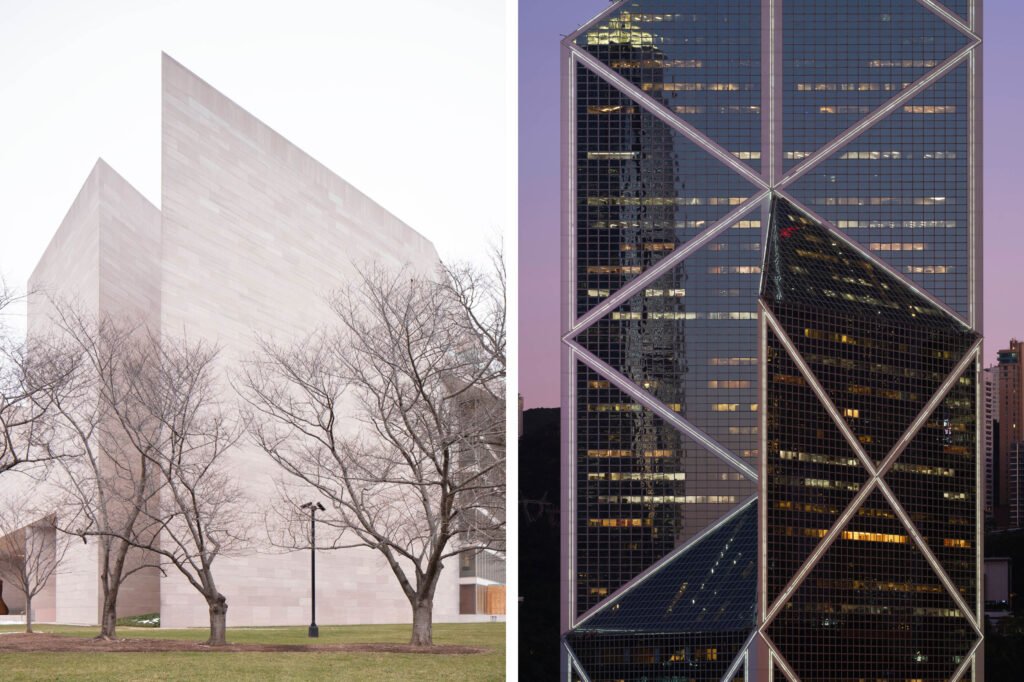

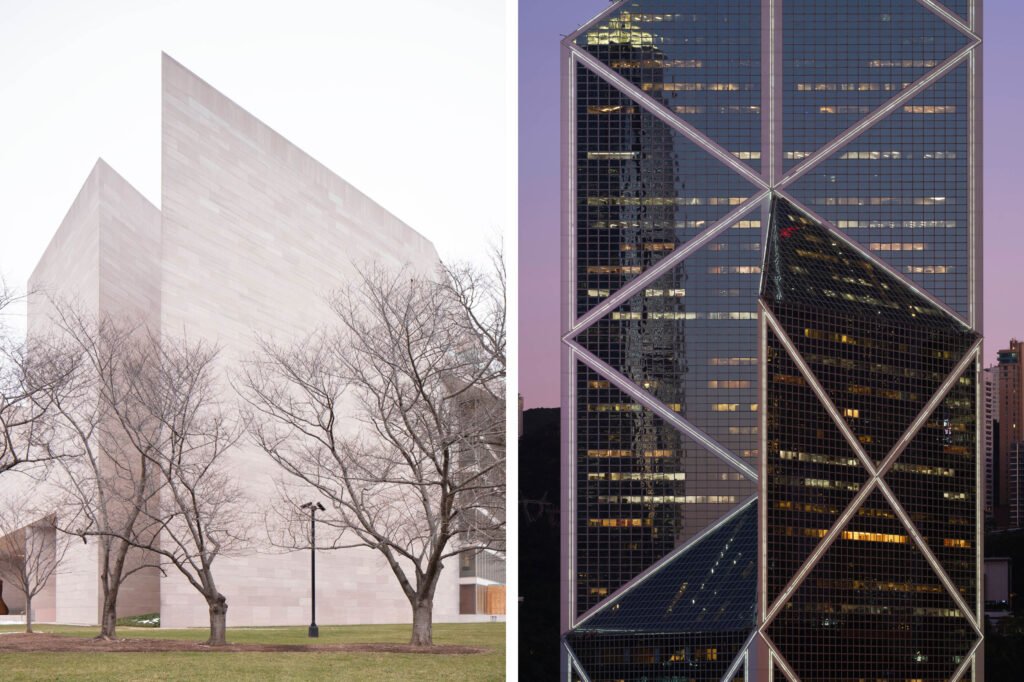

With Pei’s iconic Bank of China Tower visible across the harbor—one of only two creations in Hong Kong—I had the honor of interviewing Shirley Surya, co-curator of the exhibition and curator of M+’s Design and Architecture team. She offered a behind-the-scenes look at the epic task of curating this exhibition and shared her thoughts on the architectural Hercules himself, a visionary whose career, much like the labors of Hercules, is defined by both intense struggle and monumental triumphs.

Hi Shirley! Welcome to Kanto! For people who only recognize I. M. Pei, by name, is known for reshaping cities with projects like the Grand Louvre and the Bank of China Tower, which is winking at us right outside the window. What would you say are qualities of Mr. Pei’s work that have led to an enduring architectural legacy, and how does this exhibition highlight the depth and diversity of his contributions?

Shirley Surya, co-curator of the I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture exhibition at the M+: Hello Patrick! Wow, it’s not so easy to address the question of Pei’s enduring legacy, especially to those unfamiliar with his work. The exhibition was aimed at both architects and the general public, but more the public. Many people may not know Pei, but they know his buildings. The Louvre is a good example—everyone knows the Louvre.

Exactly.

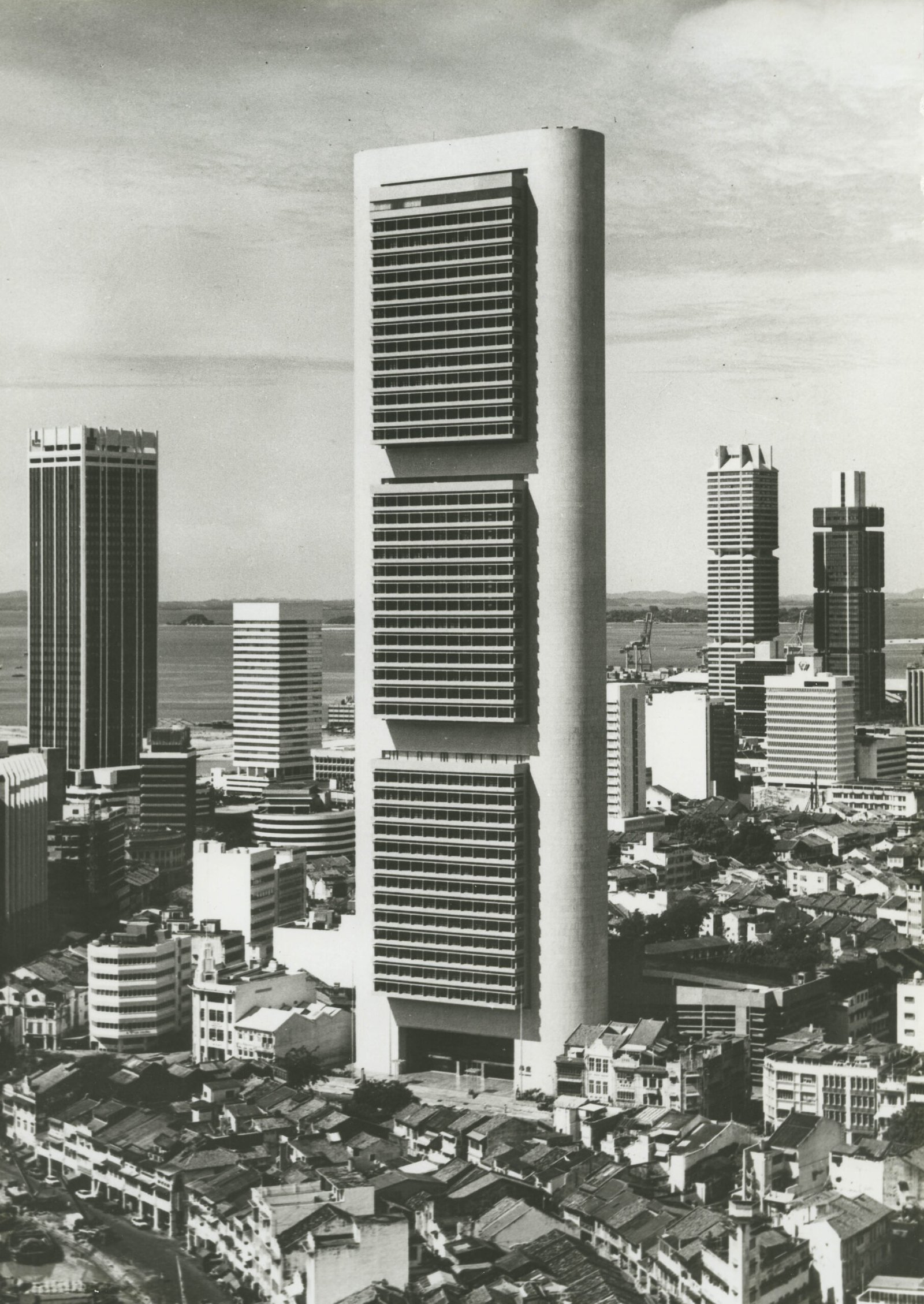

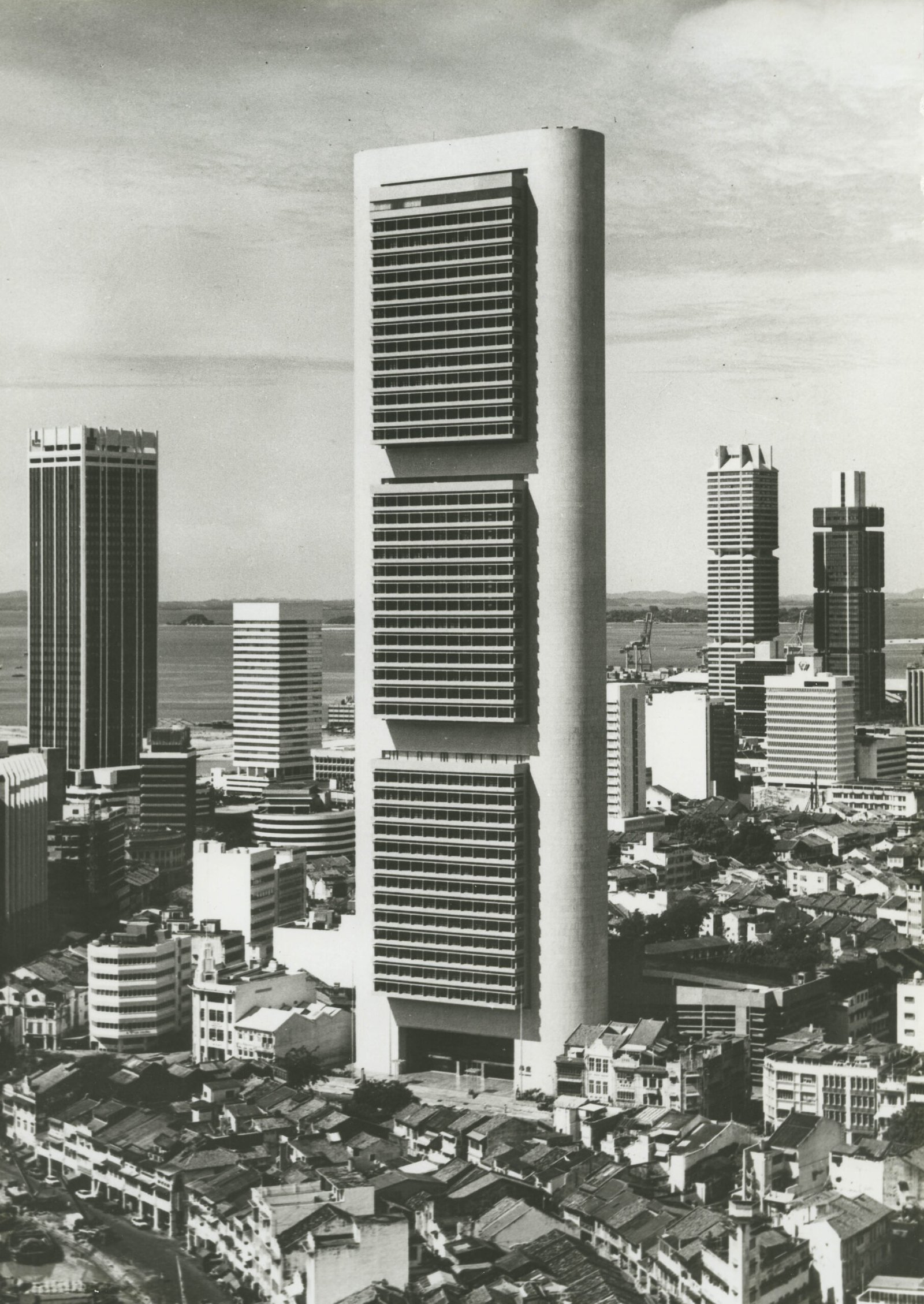

Surya: Even in Singapore, people recognize buildings like the OCBC Centre. So, for many, their entry point to Pei is through his buildings, not necessarily an understanding of him as an architect.

We chose to exhibit him for two main reasons. First, from the perspective of architectural history, he’s an important figure. Second, you can’t deny the historical significance of his projects in transforming cities and institutions, whether or not you’re a fan of Pei’s work. People may say he’s old-fashioned, but that’s missing the point. His buildings have profoundly impacted cities, institutions, and regional discourse, making him rather timeless.

There’s also a question of whether Pei’s influence was more visible on architects or cities. Architects like Le Corbusier, for example, had impacted architects worldwide across generations in terms of their practice but not necessarily cities worldwide because his works were limited to particular parts of the world. Pei may have influenced both the profession and cities, but his buildings are perhaps more influential in setting a precedent or the development of a city or an institution. Yet, there have also been examples of Pei influencing a generation of architects and planners, such as Liu Thai Ker whom we invited to the exhibition opening and whom we interviewed for a video for M+’s Instagram.

The legendary Singaporean urban planner?

Surya: Yes, former chief planner of Singapore. He was involved with the master planning of Marina Bay and was part of I. M. Pei & Partners in the late 1960s. In this case, Pei’s influence is seen not only in his buildings but also through those he inspired, like Liu, especially in Asia. However, in America, Pei’s legacy is perhaps perceived differently. Some have reduced him to being the diplomatic architect, and assumed that there’s no place for Pei in the world of theory or academia. But Pei was much represented in the media—his work had appeared in magazines like Time or Vogue—at a time when architecture became a subject of concern in mass media. His legacy goes beyond academia.

You touched on many points there, but you’ve sort of addressed why now was the right time for this exhibition.

Surya: As a seven-year-long project, it was not planned for 2023 or 2024. We had considered the need to represent Pei’s work in the museum’s collection and programming since M+ was conceived. We first approached his son, Sandi Pei, in 2014 and learned that Pei’s archive was already acquired by the US Library of Congress. Pei himself didn’t agree to the exhibition until 2016. Also, it took time to locate and secure access to another group of materials kept by Pei Cobb Freed & Partners (PCF), which grew out of the firm Pei founded in 1955 as I. M. Pei & Associates. Once they granted us access, we were on! 40% of what you see in the exhibition comes from the PCF archives!

That’s fascinating.

Surya: After this exhibit, those materials will go to the library at Harvard GSD. This is why it took so long—due to the time-consuming process of securing the loans.

If you still want to discuss the depth and diversity of Pei’s work…

Surya: For sure. The exhibition isn’t an encyclopedic survey of all his projects. For the sake of depth and diversity, we wanted to emphasize key strategies that were unique to Pei. We focused on six themes illuminating both familiar and unfamiliar aspects of Pei’s work. One significant aspect is represented in the chapter on ‘Real Estate and Urban Redevelopment’, which is often negatively perceived due to its association with commercialism. However, Pei’s early training in this area was foundational to his overall practice.

Urban renewal in the late ’50s wasn’t just about profit—developers could make more by building suburban row houses. Yet, Pei and his boss, Mr. William Zeckendorf, Sr., believed in rejuvenating decaying downtown areas. Pei’s work was not just about buildings; it encompassed a vision for cities, emphasizing urban regeneration, mixed-use complexes, and low-cost housing as part of his legacy. His ethos was deeply connected to land use and city as an organism, not just the structures above.

In the chapter ‘Power, Politics and Patronage’, we also emphasized the importance of Pei’s relationships with his clients, acknowledging that architects are not the sole visionaries—clients shape projects as much as architects do. Pei had wonderful clients, like those who allowed him to build the Miho Museum, as well as challenging ones, such as the client and stakeholders behind JFK Library, which took 15 years to complete.

A chapter like “Material and Structural Innovation”, on the other hand, is a topic that should address any architectural practice. But we focused on highlighting how his office experimented on and utilized concrete to glass and steel technologies and structure.

The concrete samples were a highlight for me, and being able to touch them!

Surya: Our learning team organized that part of the display. They wanted to ensure everyone understood what materials like concrete meant, especially terms like ‘bush-hammered’, which may not be familiar to all.

“We chose to exhibit [I. M. Pei] for two main reasons. First, from the perspective of architectural history, he’s an important figure. Second, you can’t deny the historical significance of his projects in transforming cities and institutions. His buildings have profoundly impacted cities, institutions, and regional discourse, making him rather timeless.”

I’m reminded of a symposium that M+ organized back in 2017 that delved into Pei’s oeuvre. So that symposium and all the years of research culminated with the exhibit and your new monograph with publisher Thames and Hudson, correct?

Surya: Yes. The research we conducted through the ‘Rethinking Pei’ symposium we organized with Harvard GSD and HKU (University of Hong Kong) Department of Architecture in 2017 was important in expanding and deepening our study of Pei’s work for both the publication and exhibition. We knew that existing monographs on Pei, such as those by Carter Wiseman and Philip Jodidio, while thorough, weren’t quite diverse enough to demonstrate the complex factors that shaped Pei’s practice.

The monograph is critical to the show, but the exhibition goes beyond the book. The models, the videos, and other three-dimensional elements add a layer of understanding that the book doesn’t cover.

I see. It’s interesting how Pei’s career has been framed differently in academia as you’ve earlier mentioned. He’s seen as an outsider but is also deeply rooted in it through his education and teaching experience at Harvard, as gleaned from the exhibition.

Surya: Yes, but we didn’t want to present Pei’s early years in a dry, biographical way. We used the term “transcultural” rather than “cross-cultural” to emphasize how Pei navigated various worlds—not just East and West but as an insider and outsider in multiple contexts. His work transcends simple cultural categories and binaries of modernity and tradition; nationalism and colonialism; regionalism and internationalism.

It’s an enmeshing of different influences.

Surya: Yes, exactly. We chose a quote for that room, which I recently discovered is actually a line from a Chinese poem. It struck me because we often think of Pei as a modernist, but here, he references a tradition that goes deep into his heritage. The phrase “I will never feel strange in a strange land” resonates powerfully with many of us who often feel like outsiders. It reflects an openness, a desire to connect despite differences.

This mindset speaks volumes, especially in the context of Pei’s work. Walter Gropius (Editor’s note: Pei studied under the Bauhaus master and his mentee Marcel Breuer at Harvard), for instance, was influential in utilizing prefabrication and designing for the masses through rational and logical design. Yet Pei believed that existing tenets of modern architecture or International Style weren’t sufficient to address or represent diversities of culture and place. He felt the need to design solutions that reflected specific local contexts. A city like Suzhou – where he would visit his grandfather and spend time in the Lion Grove Garden (Shizilin) owned by his uncle – was a prime example of a culturally specific and uniquely formed environment.

In architectural discourse, the notion of regionalism was popularized by Kenneth Frampton’s book, Towards a Critical Regionalism, which emerged in the ’80s. Pei’s conviction for a national or regional expression, as quoted in his letter, predates Frampton. Pei explored these ideas as a Chinese student who considered what it means to design for a “New China”, not merely following an architectural trend. The model he proposed in the form of a museum of Chinese Art was even recognized by Gropius as a legitimate approach to addressing history and tradition without compromising progressive design.

This ability to synthesize seemingly divergent modes is essential.

Indeed!

I particularly enjoyed the exhibition because it is multidimensional—not just in its physical presentation but also in its conceptual depth. Unlike many exhibits that glorify the solitary genius of architects, this one highlights how Pei interacted with clients, the media, and his team, prompting further exploration of these relationships.

As noted in your release, the projects reflect the intersection of politics, culture, and society, and the exhibit effectively balances the architect’s expertise with public perception. Given that you handled over 300 objects and conducted extensive research for this exhibition, how did you select which projects and pieces best represented these intersections?

Surya: COVID was painful, but it gave us the luxury of time to find and reflect on the materials. We first saw the materials in 2019 and were surprised by their variety and quantity. After that initial visit, the pandemic hit, preventing us from subsequently selecting the materials physically.

It was an iterative process, almost like going through an inventory. I have to credit Janet Strong, our senior researcher. As the former communications advisor and archivist at PCF, she was deeply familiar with the materials and invaluable in sorting through the archives at PCF and Library of Congress, and unearthing lesser-known projects.

For example, we specifically requested materials on Tunghai University in Taiwan. This project is significant because previous publications overlooked it; they’ve focused solely on the Luce Memorial Chapel without recognizing the importance of the campus that it was part of. Some architects in Taiwan have also assumed that Pei was not involved in the campus design, especially when Pei was moonlighting for this project while dealing with Webb and Knapp projects. But this project connected Pei back to his earlier work, the unbuilt Huatung University in Shanghai with Walter Gropius’s firm The Architects Collaborative. Huatung was also developed by the same US missionary organization that founded St. John’s University and Tunghai University after they relocated to Taiwan post-1949. The project was deeply personal for Pei.

Pei’s substantial involvement was revealed when we discovered that all study sketches for the chapel and campus were in the PCF archive. It meant that the project was conceived in New York with Pei, before the project architects, Chen Chi Kwan and Chang Chao Kang, were sent to Taiwan. These sketches, as well as letters between him and the project architects, proved that he was integrally involved, even if he wasn’t physically on site.

I wanted to include this project to clarify Pei’s role and emphasize that he wasn’t merely designing isolated gems. Tunghai represents an early model of regional architecture, combining modern materials like reinforced concrete with traditional elements such as courtyard typology as organizing principle, timber framework, and ceramic tubes. This project illustrates the meeting of multiple architectural worlds.

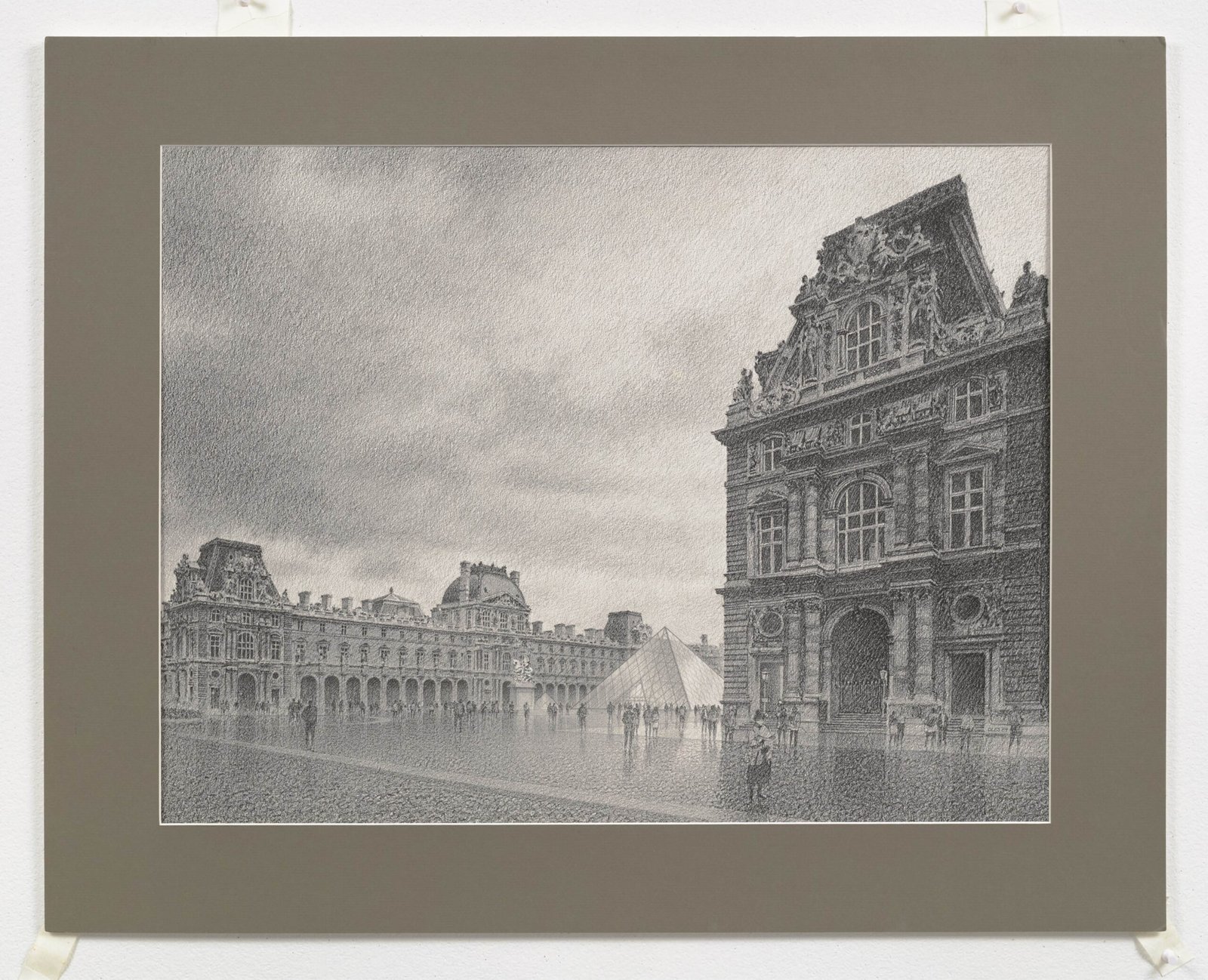

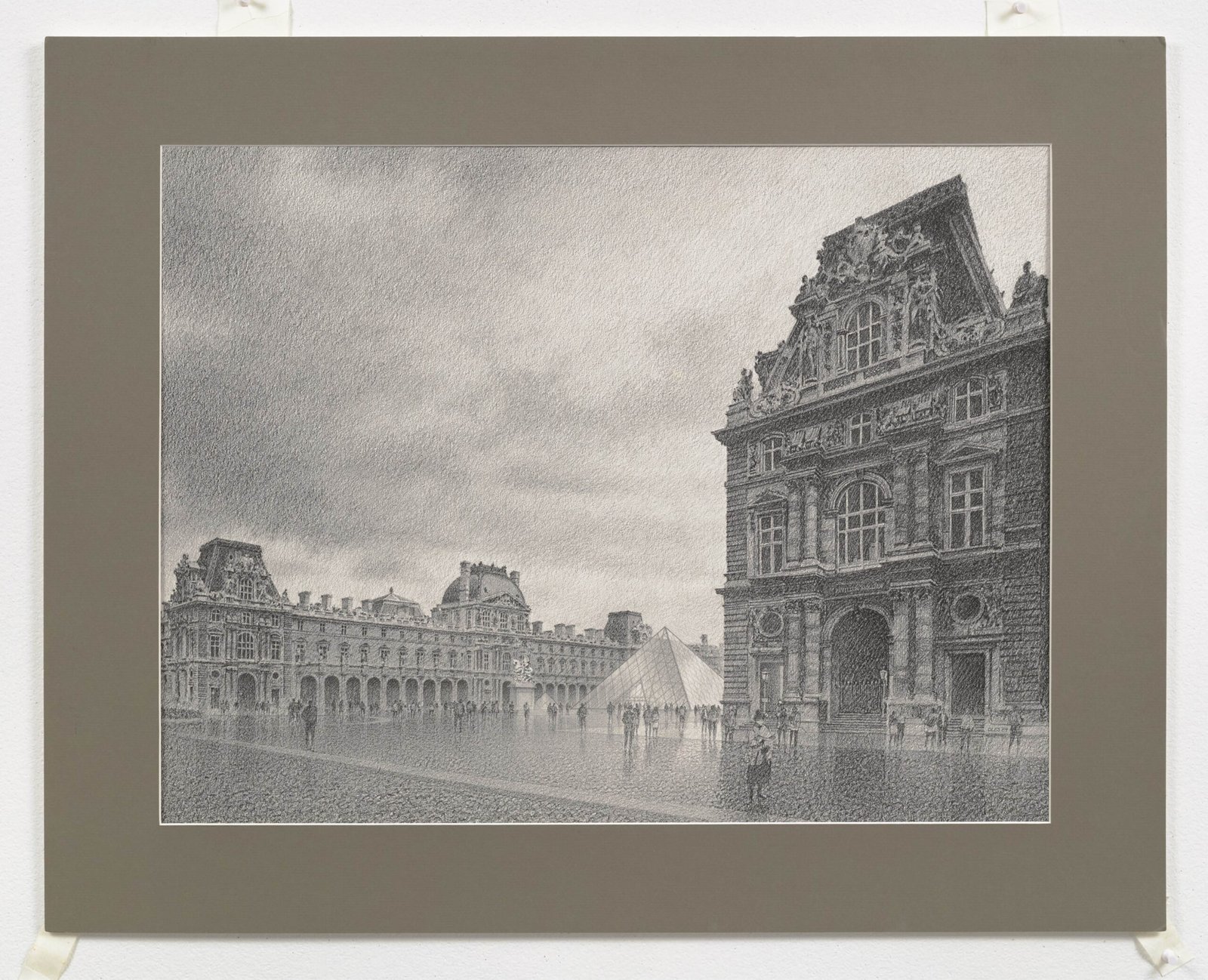

While we included iconic projects like the Bank of China Tower, we focused on those pivotal moments that marked Pei’s innovative use of materials and design strategies. For instance, we highlighted the first time he used glass in a groundbreaking way in the case of the Grand Louvre, or transformed the model of a civic museum, in the case of the National Gallery of Art.

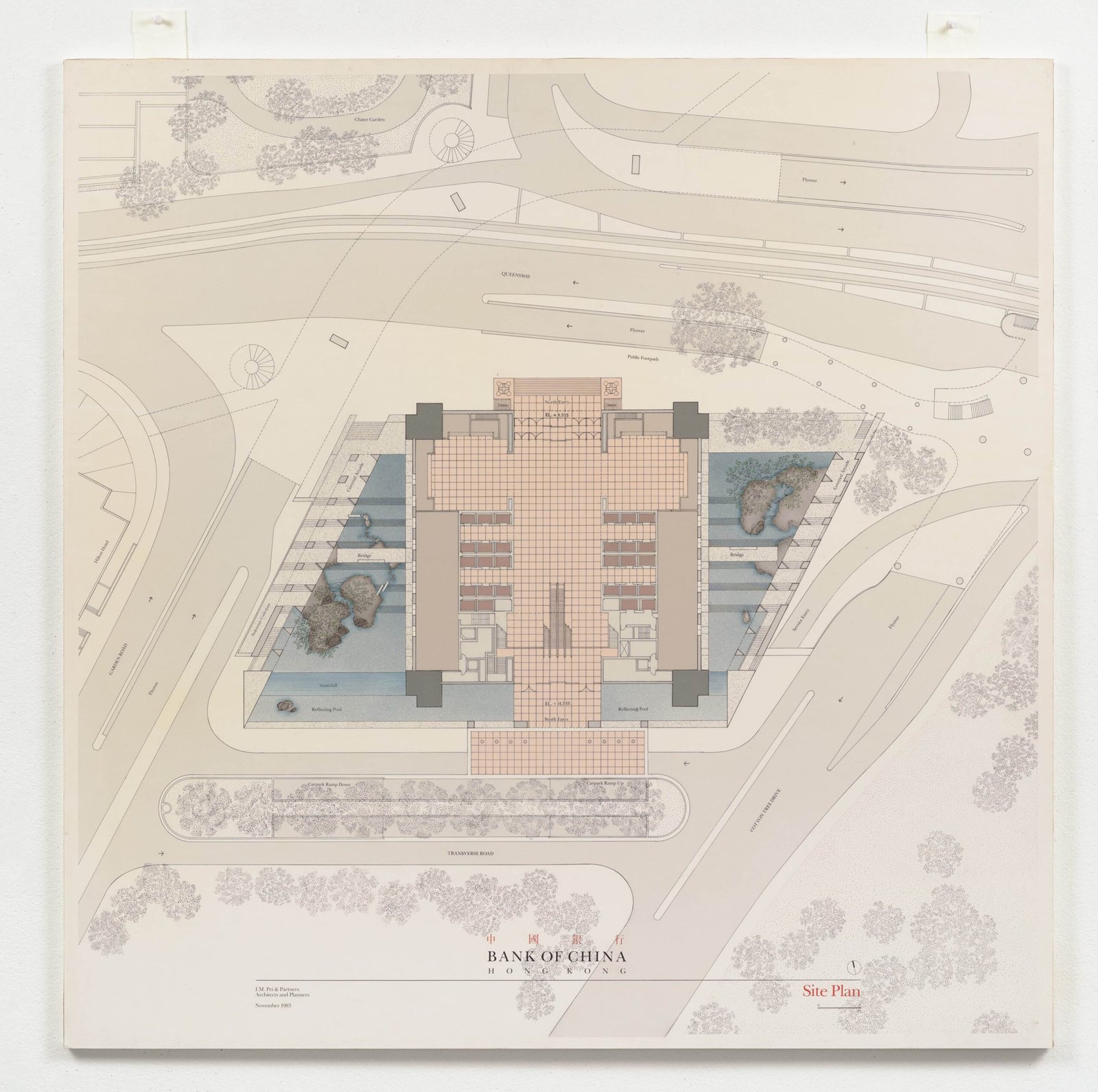

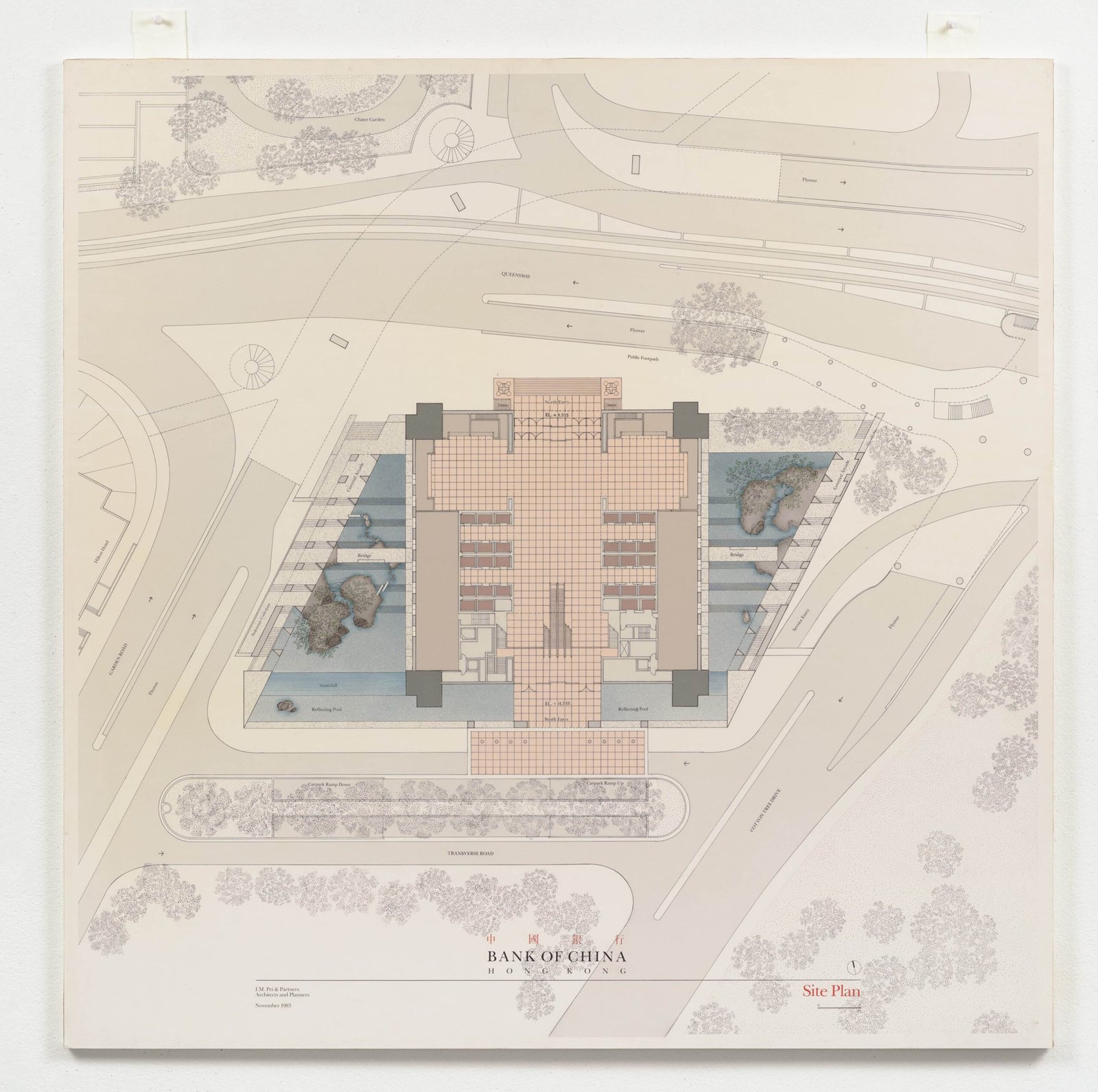

Some may wonder why we included the Bank of China Tower in multiple spots in the exhibit. We didn’t want viewers to look at individual projects in isolation; we aimed to showcase Pei’s overarching strategies. For example, the model we found for Bank of China Tower allows us to discuss the project’s site planning and its implications beyond mere tower design. The tower’s orientation in relation to Kowloon and Central is crucial—it involves land negotiation with the Hong Kong Government. Dealing with multiple stakeholders was what Pei was trained in during the days of Webb and Knapp.

In the chapter on “Material and Structural Innovation, we address the project’s integration of form and structure, which was vital to enabling the building to soar much taller than the neighboring HSBC building despite it having one-seventh of HSBC’s budget.

Finally, in the chapter “Reinterpreting History through Design”, we addressed the garden at the base of the tower, whose presence was often misunderstood. Critics might see its explicit reference to the Chinese garden as disjunctive from the tower’s curtain wall design, questioning why Pei embraced Orientalist elements. For me, it’s vital to situate the design of this terraced garden for the purpose of giving the tower a dignified framing as well as in the context of Pei’s evolving interpretation and use of the Chinese garden typology. Each interpretation is dynamic; he doesn’t replicate historical forms but reinvents them. His relationship with history is fluid, shaped by the programmatic needs of a project, which is a crucial argument I wanted to present.

I had initial ideas about the stories I wanted to convey, but we needed concrete evidence to support them. You must combine the theoretical arguments with physical artifacts, which is a challenge.

That makes sense. Finding new information could shift your narrative completely.

Surya: Exactly, and that’s how we selected materials for the exhibit.

Now it’s pretty clear why this process took seven years (laughs)

Surya: Yes, we conducted an extensive inventory. For Tunghai, we laid everything out on a table—every sketch. We reviewed everything that was available meticulously and rationalized each selection. There was pressure to try to not overlook certain aspects of Mr. Pei’s work. It’s as if you feel a sense of responsibility to represent him accurately.

There’s a certain irony to I. M. Pei—his work is so public, yet there’s so much more to him that I’m discovering through this exhibit. It reveals his complexity beyond just the provocative buildings and geometries. My favorite part was the section discussing his formative years.

Surya: Room one?

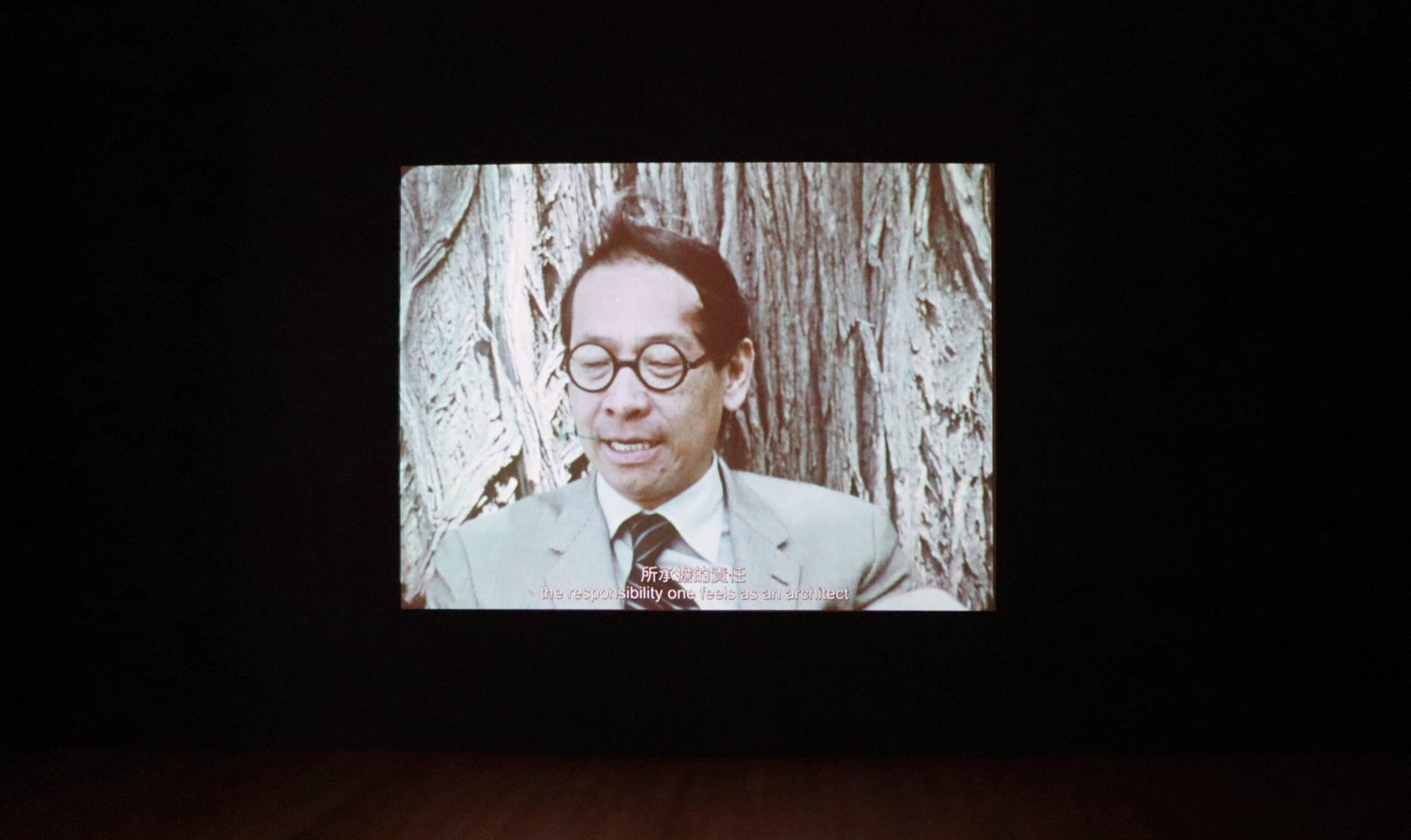

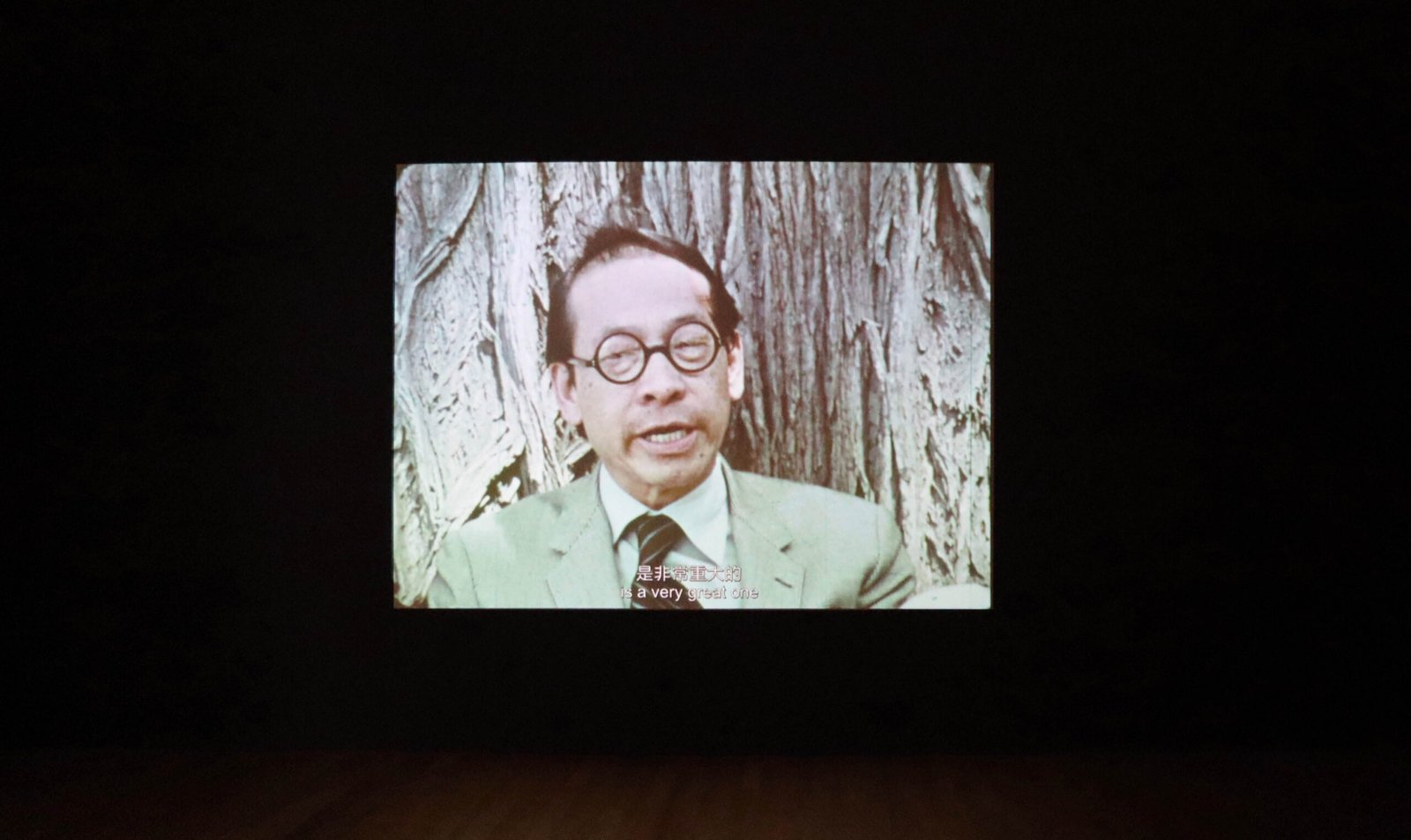

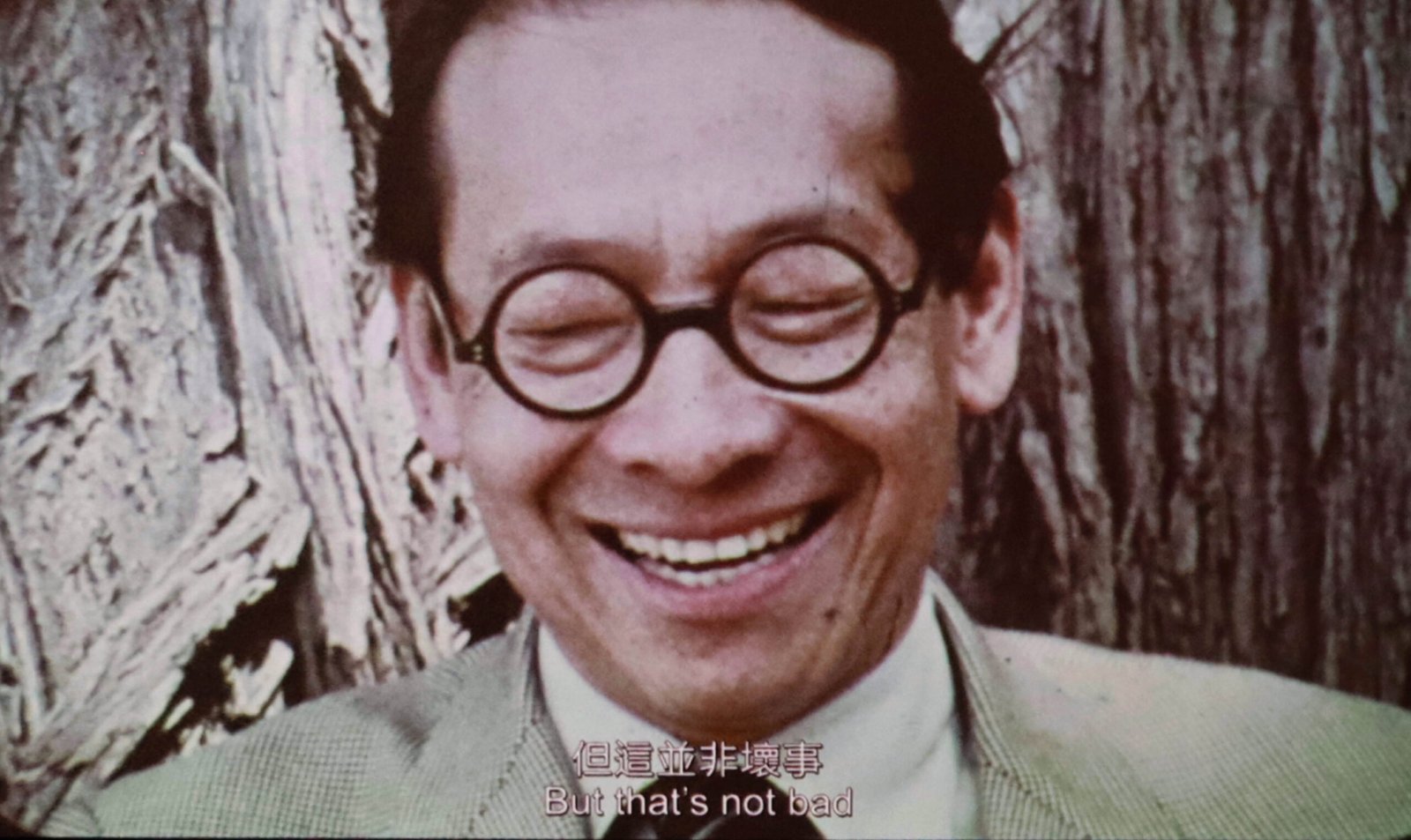

Yes, that one! The focus on the transcultural exchanges that shaped him was quite memorable! And of course, the final room, all dark with just Mr. Pei himself sitting under the shade of a tree onscreen. The way he reflected on his buildings almost brought me to tears. I did not expect his candor, and you can sense the bittersweetness in his monologue.

Surya: Haha! It’s interesting how responses vary when it comes to that final section.

I appreciate his honesty. Would an architect at his level usually admit to having mixed feelings about their work once it’s built?

Surya: Right? It’s fascinating. However, a well-known Dutch architect visited and later sent Aric Chen, co-curator of the exhibition, a message on how he found the sincerity of the footage ‘dubious’.

How can it be dubious? The pauses took so long that if it were scripted, it would be apparent! [laughs]

Surya: That perspective reflects the biases some have about Pei. They have a preconceived notion of him as a designer that doesn’t evolve.

And Pei is coming from a generation—correct me if I’m wrong—but I understand he represents this notion of the solitary genius. It’s refreshing to hear insights that show that solitary genius is not infallible. We tend to glorify legendary architects as if everything they did was magnificent. But here’s Pei, who isn’t entirely sold on even the works that established his name. I find that refreshing!

Surya: Yeah, we were very grateful to WGBH – Boston-based public television company that did the interview in 1970. We were amazed that these documentaries existed. We only discovered all of them last June. The videos came last in our ‘inventory.’ Thanks to Pei Cobb Freed & Partners and Janet Strong, they kept all the VCDs of these old films. We were like, “That’s it! This is what we need.” But getting the rights for all of them was the most challenging part; they were all old clips. Some of which we could no longer find the producers.

Haha! How they made Pei wear a tie and sit on the ground under the shade of a tree… that’s fantastic!

Surya: It was so natural! It was very thoughtful staging.

I know I’m heaping praise, but I love how the show brought out the human aspect of I. M. Pei’s work is often lost when people discuss his grand projects. The way things were unpacked in the exhibit shows that he’s very concerned about the human experience.

Surya: Absolutely. No high theory—it’s very everyday. We also want to show the multiple players behind Pei’s project and appreciate their contributions. Some people expected to see more of the architect’s hand in the work. They wanted that emphasis. But architectural production, especially in Pei’s office. We tried to credit the drawings done by Pei’s staff.

I love that you credited the artists who did the actual drawings.

Surya: If we knew who did them, we credited them. Some names were unknown, but we had to recognize that it was a collaborative effort.

The drawings are gorgeous!

Surya: Sandi Pei, his son, will tell you that his dad’s way of working isn’t necessarily like an architect that produces the single gestural sketch, like Frank Gehry. Pei was known to encourage everyone on his team to do multiple iterations—10 or more—and he will design on top of their proposals. It’s a collaborative process. Each person in the project was also known to be involved throughout the project. Everyone is honed to develop a particular expertise. For example, someone like Michael D. Flynn has grown to be curtain wall expert after working on numerous projects at PCF.

It’s great to hear about Mr. Pei’s mentoring style!

We touched on this early on, but let’s now discuss public reaction. How has the public responded to the exhibition so far?

Surya: Negative feedback, or…

Oh, any! It can be either. Positive, negative, or even offbeat reactions you did not anticipate.

Surya: Well, the most detailed feedback is on this Chinese social media platform called Little Red Book. As someone who reads Chinese, I was amazed at their responses. Some have analyzed Pei and his work even more than we did. Some acknowledged some materials as ‘new evidence’, while others built on what were presented in the exhibition. They would make comparisons and contrasts. They even made narrated videos. One might not understand what they say in Mandarin, but you can tell their enthusiasm. It’s surprising, really. People are drawn to Pei not just as an architect but as a person. After seeing the show, architects visit his buildings and compare models with the real structures, like the Luce Chapel in Taiwan.

That enthusiasm is incredible, and welcome!

Surya: It really is. Of course, there are people who had complaints about the show. Though, I’d rather have a negative opinion than no opinion at all. Some people felt there wasn’t enough material—“Why so little stuff?” they ask. I said, “I wish I could provide more if we had the materials, but we don’t.” We had to be confident in how much and how we present each project. There’s a balance to strike. Unlike the architectural audience who desire to see more, the general public can be overwhelmed by a plethora of materials. There’s a limit to how much data they can absorb, especially when it comes to architectural drawings and sketches which are not easy to decipher. My learning team had to reduce the quantity of materials representing each project, to focus on visuals over textual, to present only the most important aspects of the work that contribute to the arguments of each theme.

The significant bits that you can’t skip.

Surya: Exactly. But architects want more, and I have to remind them that either we only display materials that are available or that we can’t show everything.

I mean, this is the first exhibit. There can always be a second.

Surya: That’s a great point, but doing a second show on Pei will be pretty challenging for anyone.

For sure, the first one took a while.

Surya: If someone manages to do a second, it would be comforting for us. We include all the bibliographies in the book so people can use those sources as evidence for their arguments.

Ultimately, it’s not just about Pei. The subject of Pei offers another lens for examining architecture in this part of the world or transnationally. We wanted to plant those seeds. The significance of this project lies in how it encourages people to look at architecture differently.

Like you, I come from a media studies background but with an architecture focus. I’m very aware of design history. When studying design history as opposed to architecture, we examine production, consumption, and mediation. The media’s portrayal of design or architecture is crucial as it reveals disjunctiveness or alignment. It creates a full cycle of what these objects are and what they mean.

Public touchpoints, like exhibitions, contribute to that. I’m glad you had that little corner for architectural media. Architectural media is widespread but often overlooked in terms of its influence on shaping public perceptions of architecture.

Surya: Yes! Especially in the period before the internet.

Right. They had a grip on the narratives and access to architects and projects. They were single-handedly establishing the narrative to share. Now, with platforms like TikTok, ArchDaily, and Dezeen, there’s an assortment of ways to engage with architecture.

Surya: Good and bad, right?

Absolutely, good and bad. But there’s a multifaceted discussion available if you want to engage.

Surya: Exactly.

“Ultimately, it’s not just about Pei. The subject of Pei offers another lens for examining architecture in this part of the world or transnationally. We wanted to plant those seeds. The significance of this project lies in how it encourages people to look at architecture differently.”

You mentioned that you already had an interest in pursuing a show on I. M. Pei early in your time at the M+. Given the exhibit’s context, I’m curious about your research on Pei’s experience in Hong Kong. He spent around a decade here, yet surprisingly, that only resulted in two commissions.

Surya: We very deliberately let go of certain aspects of Pei’s personal life. We felt whatever he did outside his architectural practice could distract from the main focus. For example, we didn’t include personal anecdotes like him loving Hong Kong food or tailoring his suits here. However, it was important to include aspects of his upbringing, as we did in Chapter 1 – especially on his father’s role in setting up the main branch of Bank of China in Hong Kong, which led the family to Hong Kong and Pei’s exposure to a urban cosmopolitan, albeit colonial, environment.

I was looking for a link since the exhibit is significant and happening specifically in Hong Kong.

Surya: I suppose the strongest link is between the nature of M+ as an institution and the nature of Pei’s life and practice. As a Hong Kong-based and Asia-focused institution looking at the world transnationally, we felt that there couldn’t be a more fitting venue to present Pei’s transnational practice as a Chinese-born American architect whose work have influenced cities around the world.

In many ways, this show is better suited to discussing Mr. Pei’s work here than anywhere else. If the exhibition were held in the U.S., it would likely focus solely on his American projects, overlooking the significance of those in places like Singapore or Taiwan. The transnational framework—where Hong Kong and M+ are situated—is perfect for this.

I see. Okay, now I couldn’t imagine it being anywhere else.

Surya: Exactly. People often ask why we didn’t choose architects like Zaha Hadid, BIG, or Kenzo Tange. They are influential architects, but they don’t resonate with our remit as strongly as Pei. Pei grew up here, he connected deeply with the Asian region. While Kenzo Tange also addresses regional issues, he wouldn’t cover the U.S. and international aspects as comprehensively as Pei does. Few architects address the Middle East, Japan, and France as he does.

I guess it’s a skill and a sensibility at the same time. Not everyone can work in different places and still create a building that eventually becomes rooted in its location. Take the Louvre Pyramid, for example. It took a while, but now you cannot imagine the Louvre without that entrance. Yet, some buildings have been loathed since day one and are still not embraced today.

Moving on. What specific principles from Pei’s work do you think architects could apply to contemporary challenges, and why are they relevant?

Surya: At the 2023 Venice Biennale, the Swiss Pavilion focused on neighborliness. This concept involved engaging in dialogue with neighboring pavilions. I think Pei was keenly aware of something similar. Of course, not every building fits this model; for instance, the Bank of China Tower is set in tight urban conditions, while the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Colorado stands alone. The National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. is also awkwardly situated, having to address an older wing. Fragrant Hill Hotel (in Beijing) and Miho Museum (near Kyoto) also stand independently. Even the JFK Presidential Library, despite not being ideally located, was designed with a sense of neighborliness, which doesn’t always mean engaging the next building; it encompasses being sensitive to the widest context of the building’s site.

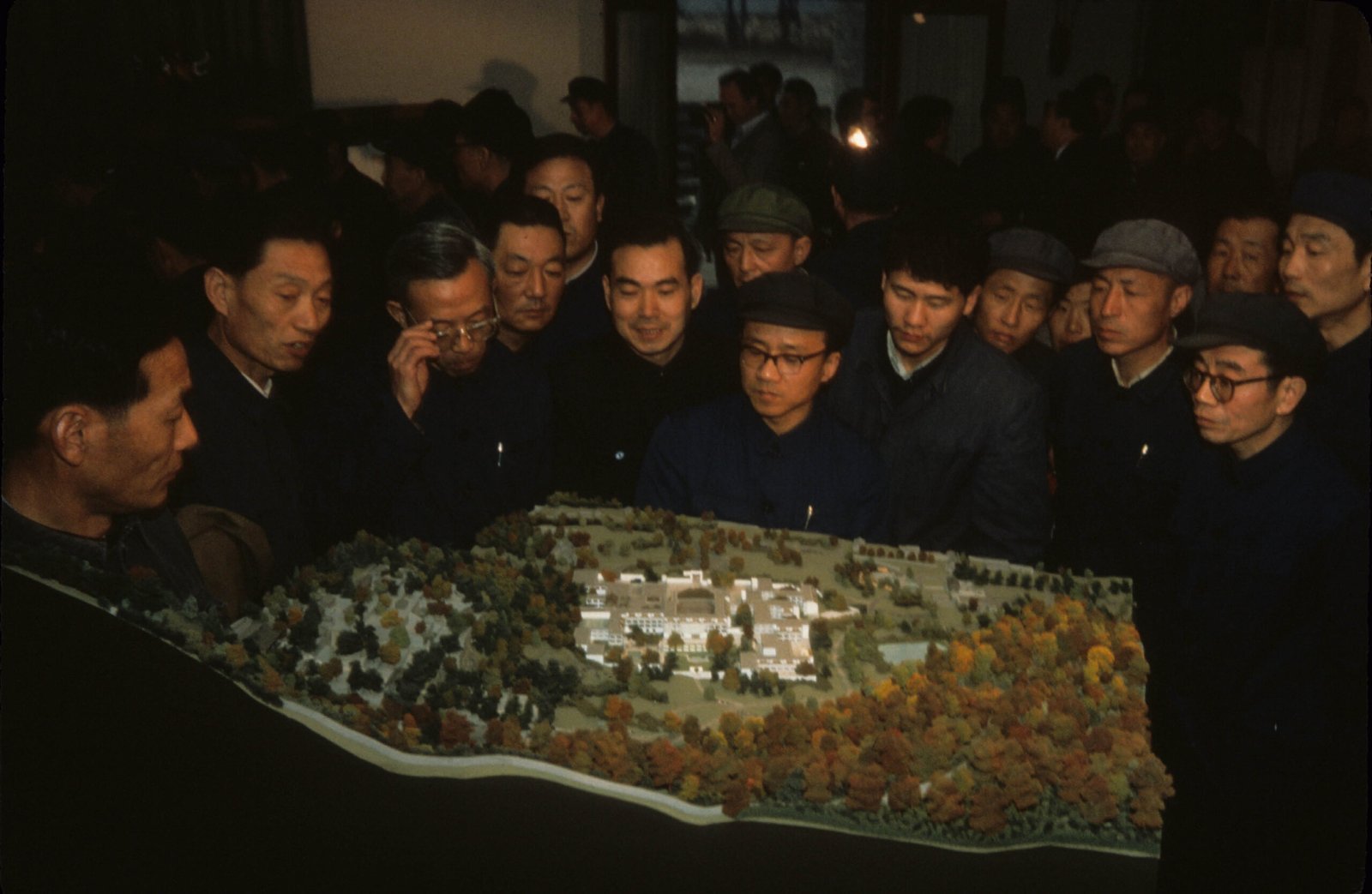

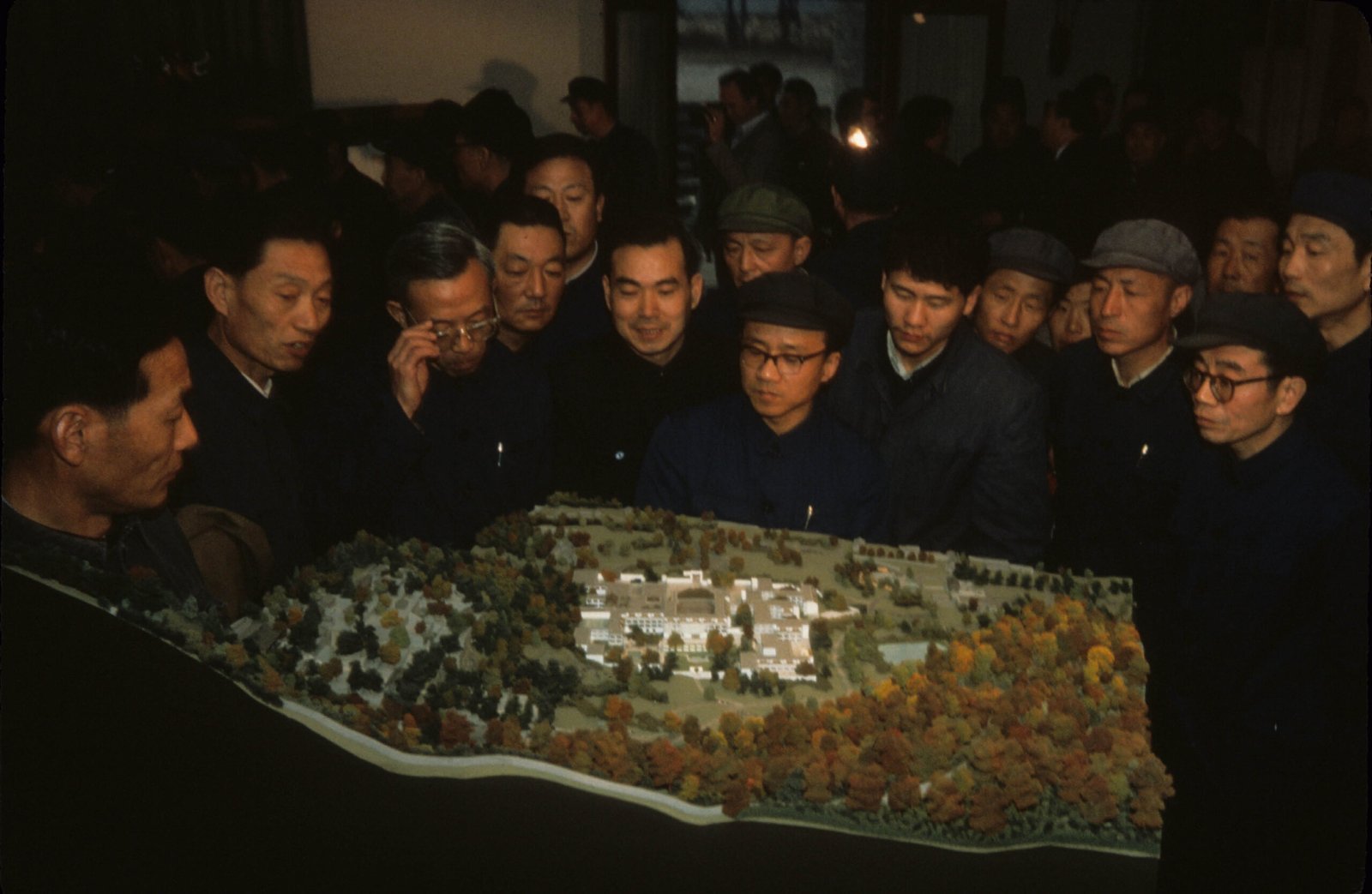

The models that remained in Pei Cobb Freed’s archive were all site models, in which the building was presented as part of a much larger site. When handed that giant-scale model reflecting Pei’s vision for Marina Bay in Singapore, Liu Thai Ker mentioned, “That’s Mr. Pei.” He was not satisfied with just a building model; the site extends far beyond because the building needs to be understood within its context. This level of vision and scale of thinking is quite rare.

It’s not just about practical aspects like traffic circulation or building access; even small details matter to him. This focus is vital. The other aspect is in the room on “Reinterpreting History through Design”. If you look at the project he designed in Doha for the Qatari family (The Museum of Islamic Art) and compare this with M+, each sought to address the region, but how? Pei demonstrated an ability to move beyond generic regional associations. He sought particular traditional typologies or conditions, abstracting and creating something unique, by having the Mosque of Ibn Tulun as a point of departure. That move is also extant here at M+, with Herzog & de Meuron’s homage to traditional Chinese clay roof tiles and ceramics or the tower-podium typology of Hong Kong. That process can’t be easily copied, but it inspires others to delve deeper, moving beyond the generic. Understanding what it means to reshape or reinterpret is truly remarkable.

I love that perspective. It’s not just reactive; he’s willing to reflect on his reactions and isn’t afraid to dig deeper. For instance, he would question why something was designed a certain way hundreds of years ago.

Modern architects could learn from this willingness to go beyond cultural tokenism—simply blowing up national symbols or elements. They should take the time to explore culture and sensibilities, not just the physical objects associated with them.

In the Philippines, we have a word, maaliwalas, with no direct English equivalent. It is a quality of a space that conveys lightness or buoyancy and provides comfort—deeply connected to our tropical architectural identity in the 1960s and 1970s. Filipino architects have different interpretations of this idea, a multilingual quality that also resonates in Pei’s work.

As a side note, you mentioned that critical regionalism made its academic debut in the 80s through Frampton, but Pei was already making strides in that direction as a student.

Surya: Exactly!

This might also interest you. Filipino architect and National Artist Leandro Locsin reminds me of that same mindset—unafraid to engage with history. Modernists often wanted to erase the past, but Locsin embraced it early in his career, which began roughly at the same time as Pei’s.

Locsin always comes up first when discussing Philippine architecture because he valued the past. He reflected on what worked and how it influenced present spaces, much like Pei did. For us in the Philippines, his designs were both modern and familiar—something few architects achieve.

Surya: There’s a risk of going to the other extreme, becoming fetishistic about history or tradition, resulting in something inappropriate for contemporary use.

That is indeed a danger.

Surya: In fact, we included Pei’s letter to a Beijing-based architect Wu Liangyong in the exhibit for the Suzhou Museum. It captures his argument about engaging with history. Essentially, he conveys that one can respect history without being derivative. He understood what a contemporary museum requires; for him, bringing light through the roof was more crucial than adhering strictly to tradition. Many architects in China recommended him to use traditional clay tiles. But Pei insisted on a multi-tiered steel roof to enhance the museum experience, prioritizing that over conformity.

His approach to history is dynamic, seeking to integrate it with contemporary use. For the Luxembourg project (MUDAM), which remained unbuilt for 15 years, he proposed an entrance through a seventeenth-century fort, illustrating that for Pei, history is a living thing. It must connect with how we use buildings, accommodating new programs and materials.

You could call it balance, though I find that term lacking. It’s about maintaining a productive tension while fostering a complementary relationship between past and present—a difficult feat not everyone can achieve.

It’s about architects initiating conversations with the past. They build not just from scratch but on the foundation of extant narratives, continuing the story, so to speak. That’s a powerful observation.

Surya: Different projects necessitate different approaches. Take OCBC Centre in Singapore, where the requirement was to build a skyscraper in a packed neighborhood. With the Bank of China Tower, addressing history wasn’t necessary; it depends on the project.

…and the context.

Surya: …and the situation, the nature of the project.

Here’s a fun question: if I. M. Pei himself were to visit the exhibition today, what do you think he would find most gratifying about the perception regarding his work, and what aspects might he challenge or provoke further discussion on?

Surya: Oh that’s hard to imagine!

[laughs]

Surya: Sorry, I find that a tricky question to answer. I never met Mr. Pei. My understanding of him comes solely from what I’ve read and observed. Speculating on his thoughts now versus when he was younger is tricky—he’s bound to have changed significantly over time.

I don’t know how to answer that. I’d be more interested in what I’d ask him rather than guessing his opinions. I don’t want to presume. One journalist posed a question similar to mine. I said, “Mr. Pei, do you really believe your commercial buildings aren’t good enough?” He had expressed that sentiment before. I wanted him to see the importance of those projects, to convey that they matter just as much as his iconic museum designs. He faced criticism for being commercial but was committed to keeping his firm alive and supporting his team.

He took on commercial projects but maintained his vision and rigor. I’d want to tell him that. I was shocked when I saw interviews where he expressed lesser regard for his buildings. Some journalists echoed that sentiment, labeling his commercial projects as unimportant. I found that troubling. As a historian and curator, I realized that discussing buildings from multiple perspectives is crucial—not just the architect’s view.

I think he’d appreciate that, considering you come from the user’s perspective.

Surya: A building like OCBC Centre, for example, holds significance for a city-state like Singapore, much more than what a historian in America might consider important. To me, the value of a building is represented by how the community perceives and identifies with it, which is just as important as an architectural historian’s perspective.

It becomes an indelible part of the space’s identity.

Surya: It has its own memories and uses.

I happen to like OCBC Centre; it’s actually my favorite Pei building in Singapore. Despite his newer projects, it’s the one I feel is most confident in its identity.

I guess I’ll wrap up our conversation with this question: Were there aspects of the exhibit or Pei’s life that you wish you had more time to explore and include for the exhibit?

Surya: We had to exclude a couple of projects due to a lack of materials. Some of them are in the book, though, with limited images. One project that we didn’t include both in the book and the exhibition is Terminal 6 of JFK airport in New York that I didn’t even know he designed. It’s fascinating—one of his first glass-and-steel roofed structure was for that airport in the late sixties.

I posted it on Instagram since it was too late to include it in the book. We discovered more material, but it was too late to add. There are also older projects that were structurally pioneering.

One project we couldn’t include in the exhibition but is in the book due to a lack of materials is Gulf Oil Building (1950-1952). It was a small Miesian box office building but particularly impressive. Pei negotiated a discount for locally sourced marble in exchange for displaying the material prominently in the building’s curtain wall. Alternating panels of thin marble and glass form the walls, which were installed directly onto the prefabricated steel frame from inside eliminating the need for scaffolding. This was before Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, which also used marble panes. The difference lies in scale and that Pei’s project was a commercial not institutional building.

There’s also the air traffic control towers project in the book, showcasing his mastery of prefabrication. His team won the competition of designing a standardized control tower for all FAA (Federal Aviation Agency) airports across the U.S. The prototypical design of a tapered concrete tower in five different heights with thirteen variations was both structural and sculptural. We spent quite a long time sourcing photos of that. It’s impressive!

Wow. Control towers!

Surya: If we had more space, we’d delve deeper into these projects because, to me, they represent infrastructure, which, in the pecking order of typologies that architects tend to accept, isn’t very high on the list.

It highlights how he gives his all to every typology.

Surya: Exactly. That was key. Not many architects can design across such diverse typologies.

It was great that he had a lengthy career to bless us with work in different building types.

Surya: Definitely underrated. And sad to say, many people have already forgotten him. Our goal wasn’t just to build Pei’s so-called legacy. While the family may feel that way, and we want to contribute to that, our biggest goal as a curatorial team is to assess architecture through a transnational framework and multiple perspectives—not just about the author. We felt it was essential to showcase the diverse typologies. We’re not condemning commercial projects as inferior. There’s no preference; architecture encompasses a much wider field.

Exactly. The six exhibition chapters you created illustrate that whatever one designs does not exist in a vacuum. Once a building exists, it becomes part of the identity of the community it’s situated in, in whatever form. A building has a responsibility. As Pei said, one must take seriously how it interacts with everything around it. Many architects seem to forget that when focusing solely on creating something memorable.

Surya: True. If you ask architects about their priorities, apart from neighborliness, it often comes down to ethics. I’m not talking about ethics in a policing sense. I was shocked when some were skeptical of the last video in the exhibit while you were moved by it. Others asked, “Why so simple? Where’s the theory?” This goes back to the human aspects of architecture. Too often, it’s elevated to high theory. If it’s not theoretical, it’s not intellectual. Many believe intellectual rigor is more important than the heart of it. To me, if you can’t fulfill the heart of it, what’s the point of building?

Precisely. That’s a huge turn-off for me. If I need to learn theory to understand why your building is fantastic, then I dislike it. It suggests something fundamentally wrong with the building as a physical space; it does not establish an easy or natural dialogue between the user and the space. Something is off if I have to cross that intellectual barrier to appreciate your work.

Surya: I agree, though it’s not to say that theory isn’t important. It’s more about using it appropriately as a criterion for assessing a building.

Exactly. Theory should enhance the building’s experience for the user, not hinder it. The people using it shouldn’t be lab rats for your theory.

Surya: I get that. While we allow for diverse views, I’d strongly argue for a return to the fundamental aspects of architecture, which seem increasingly dismissed. Buildings are becoming mere icons devoid of deeper significance.

That’s a crucial point. Pei cared deeply about the environment—like parks and trees. That’s why we highlighted even something as insignificant as Pei’s introduction of a setback. It’s a big deal in Hong Kong, even if it’s often overlooked for maximum commercialization of site.

… which reminds me of the section on Sunning Plaza! I was watching the video snippet from John Woo’s A Better Tomorrow, which showed the building and a young Chow Yun-fat on loop, and I began to understand why the movie crew chose that particular location. Beyond its cinematic value, the open grounds surrounding the tower serve as both a witness and a narrator of the city’s stories, reflected in the lives of its people.

Surya: I keep telling everyone I didn’t realize the significance of that building until I came across a blog with a screenshot from that film. I hadn’t even watched it before! A Hong Konger would slap me and say, “How can you not watch that film? It’s the most iconic gangster film!” That’s when I realized they associated that building with the film. It’s crucial to discuss his buildings this way because they aren’t just skyscrapers; they also have a public aspect to them. Now, there’s a building that’s ingrained itself into the city’s identity! (Editor’s note: Sunning Plaza was demolished in 2013 for redevelopment)

Shirley, it’s been a pleasure talking to you! Thank you for your time, and congratulations to you and your team again for a splendid show! •

I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture is on show at the M+ Hong Kong’s West Gallery on Level 2 from June 29, 2024, to January 5, 2025.