Words and images Joshua Alexander Manalo

Editing The Kanto team (Vermont Coronel Jr.)

For over a decade now, I have continually supported artist Vermont “Ver” Coronel Jr. (1985, CCP Thirteen Artists Awardee, 2015) through the creation of works for the family’s Outlook Pointe Foundation collection. I consider these commissions an ongoing dialogue. Ver’s resulting works are like outlets for my obsessions, but they also speak of our shared interests: from heritage conservation, unnoticed landscapes, and landmarks in the Metro, as well as reminiscing on things from not quite long ago—we hold dear our 90s childhood upbringing through and through (“742 Evergreen Terrace”). More importantly, these commissions transmit our foundation’s vision of seeing things with a new perspective and serve as a reminder that nation-building is multi-layered.

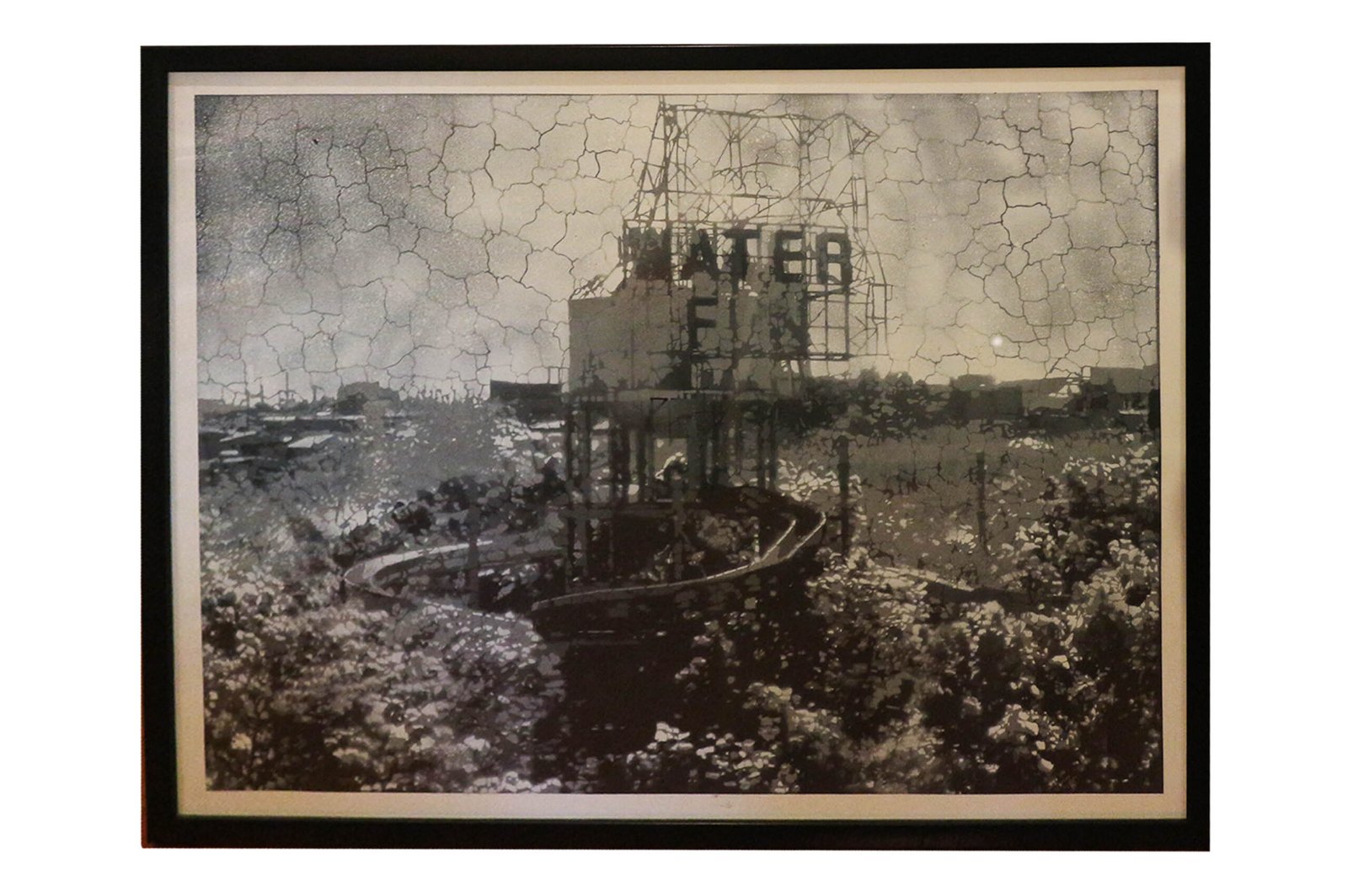

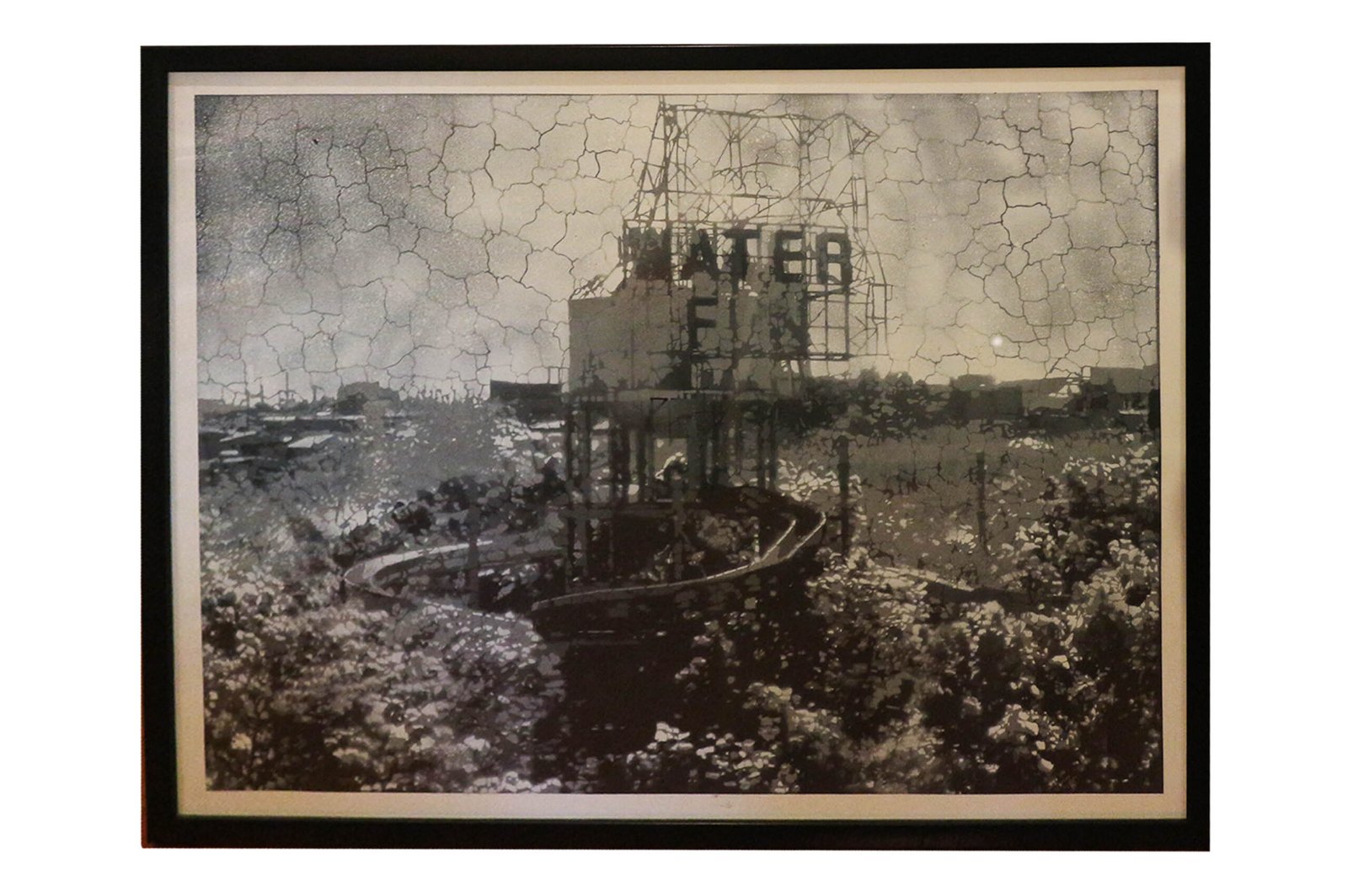

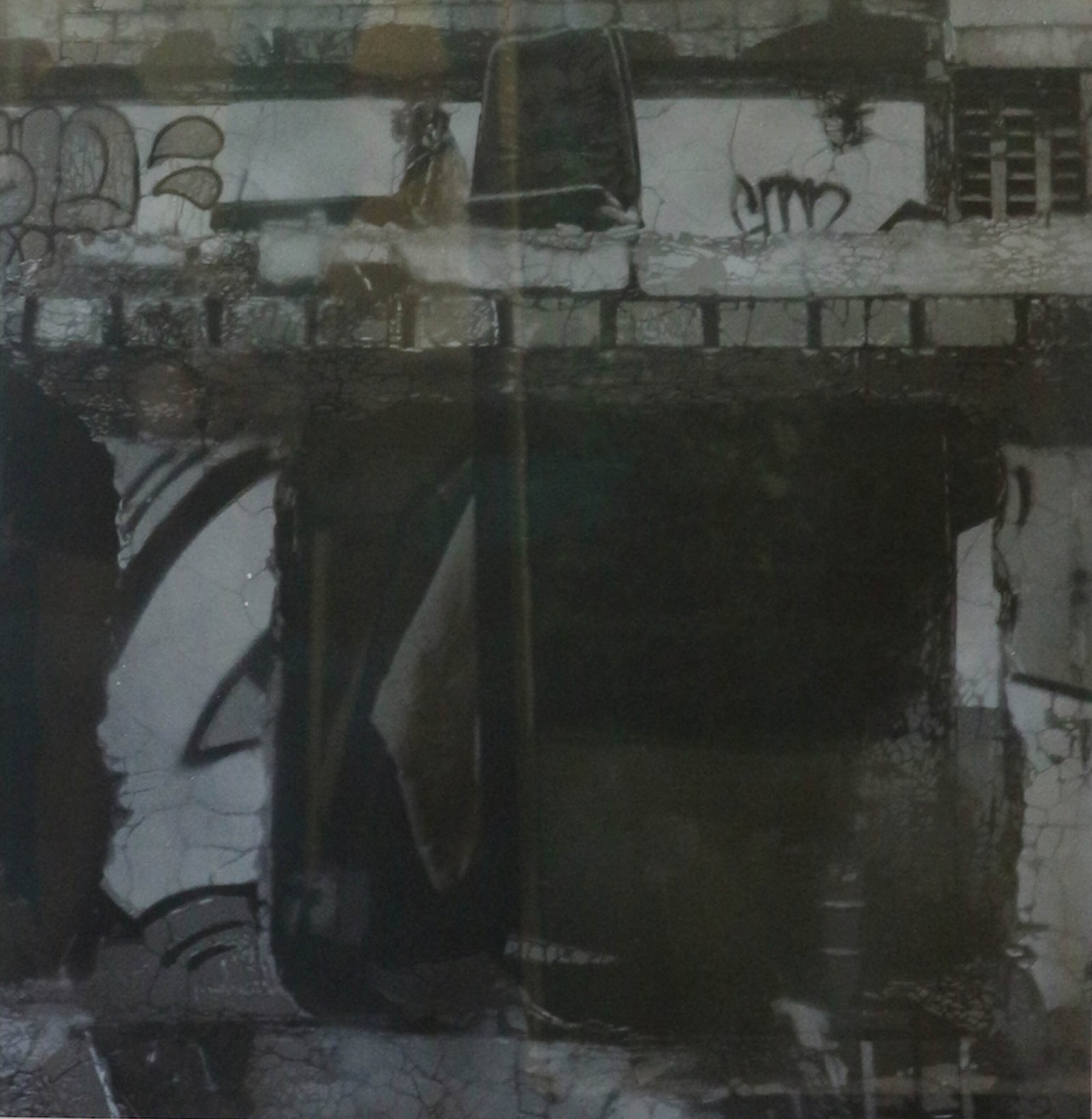

With nation-building comes the necessity of acknowledging the uniqueness of a single human being’s personal vision. For me, Ver’s works are not a thing apart and have become a central force in my life. The subject matter of his works can sometimes appear random (“Location 11”), while others are everyday sightings (“From Skyway No.1”) that continue to satisfy my curiosity for places that function like postcards of sites overlooked but not quite abandoned.

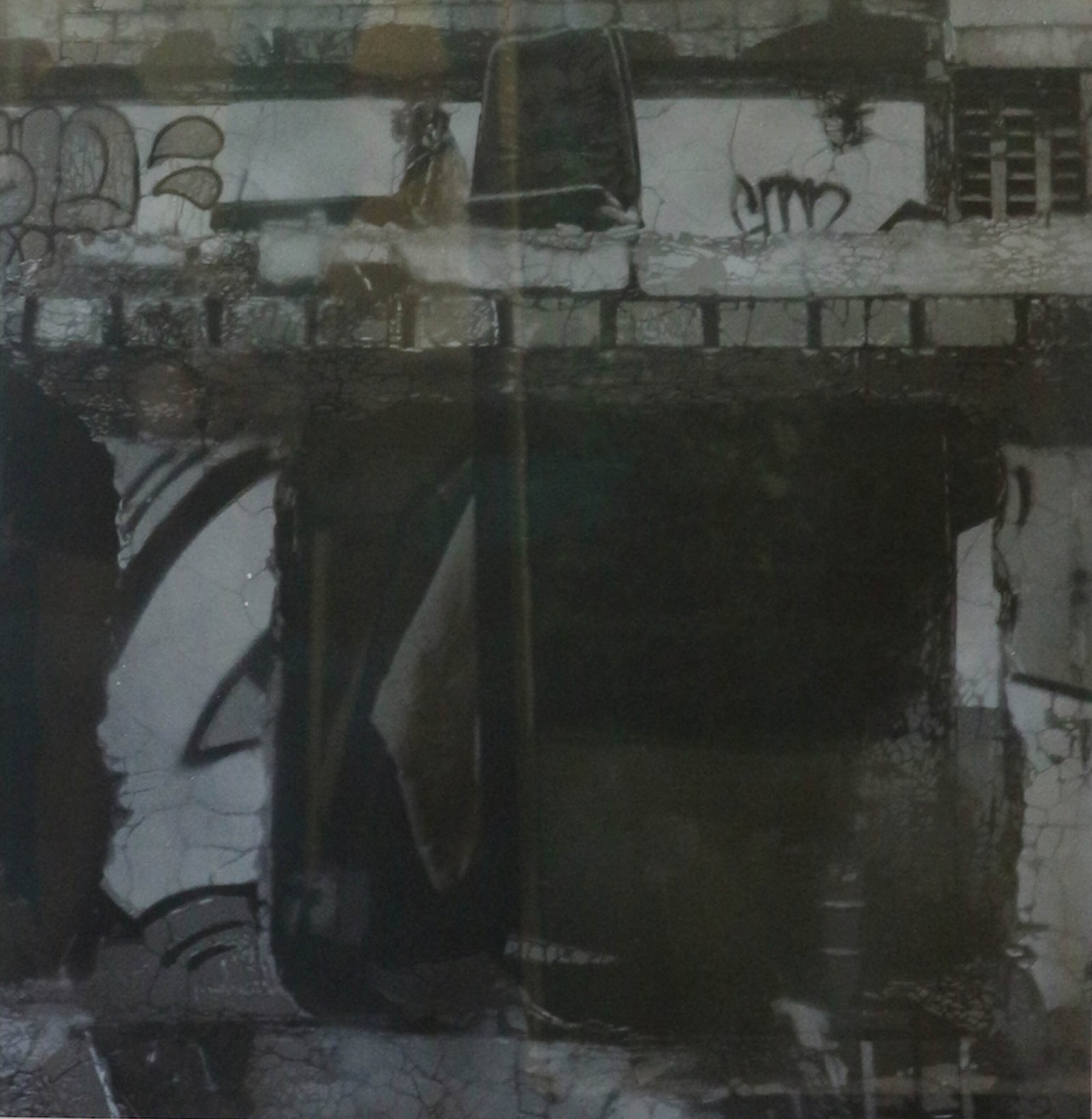

I have never seen or felt a persona in a work by Vermont Coronel Jr. He has mastered the ability to produce works in which emotions seem to grow entirely out of the subject matter. His works lack a sense of urgency to express or release. Instead, they silently rip through, slowly and surely. His monochromatic aerosol works remind me of dynamite or a ticking time bomb. His cutouts, on the other hand, remind me of a misshapen jigsaw puzzle: the shapes fit, but not necessarily the colors or tones. They are elegant disorientations. Ver’s works show me that wandering is a good thing, but it’s also good to be put back to center. To find balance.

Likewise, Ver’s process and technique draw me in. There are times when detachment creates depth, when precedents in subject matter don’t matter; it becomes a total unloading and clearing of mental clutter through work and discipline. Being in the zone. Maybe it is detachment that fuels art in the long term, because, in the end, it’s not about making fixed plans and executing them, but about analyzing possibilities and making the right choices as we go along. It is the process itself.

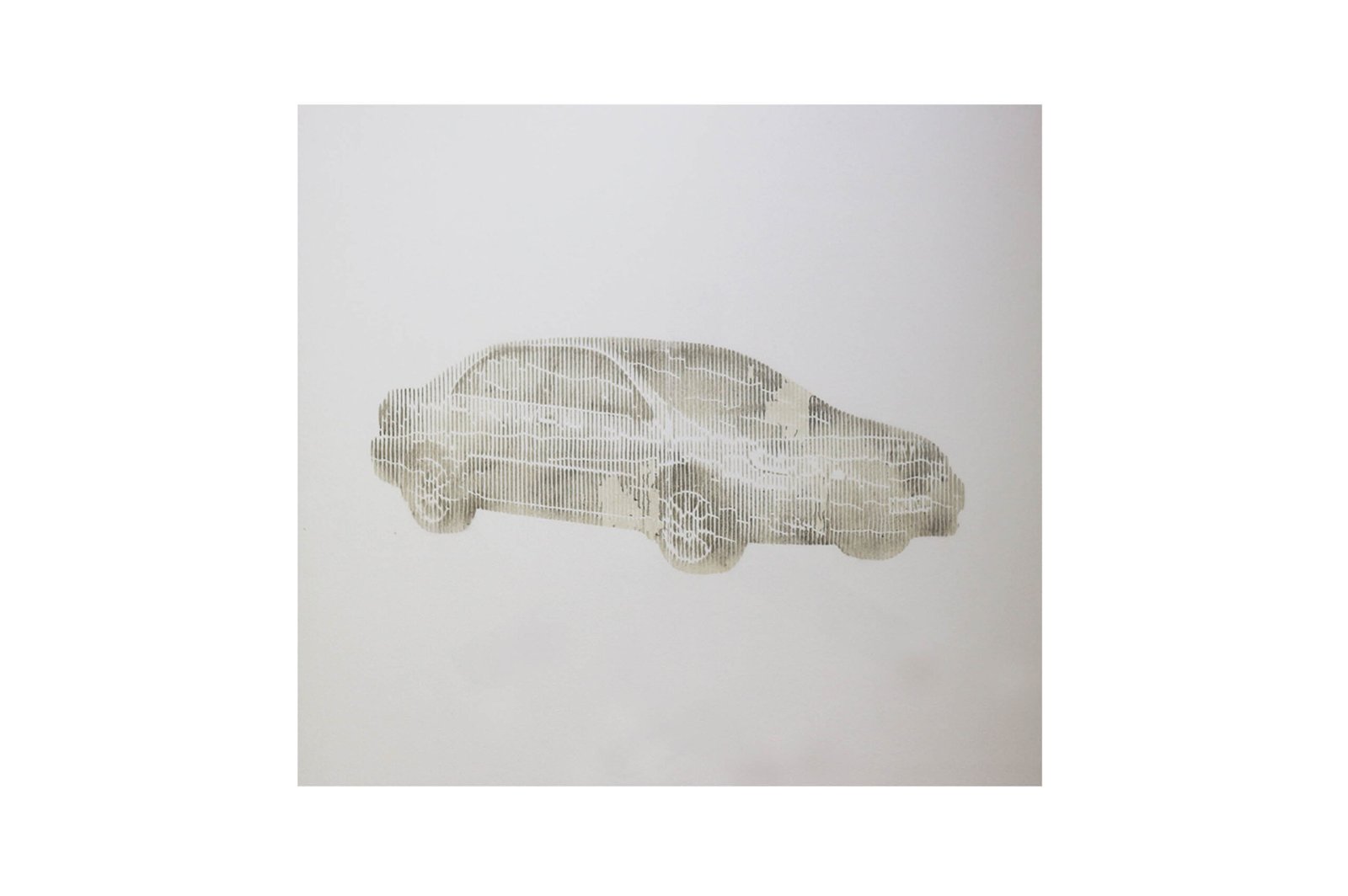

Here in Metro Manila, we are familiar with the daily struggles of dealing with a variety of seemingly simple challenges, always thinking of multiple solutions to every problem. Take being on the road in the Metro, for example: you literally have to be street-smart. Survival instinct. It is about being resourceful and determined. I’m reminded of his works made from dust (“Altis”). Ver has continually tried to explain his process to me (stencil, layering, and so on), and it’s always a work in progress for me to understand.

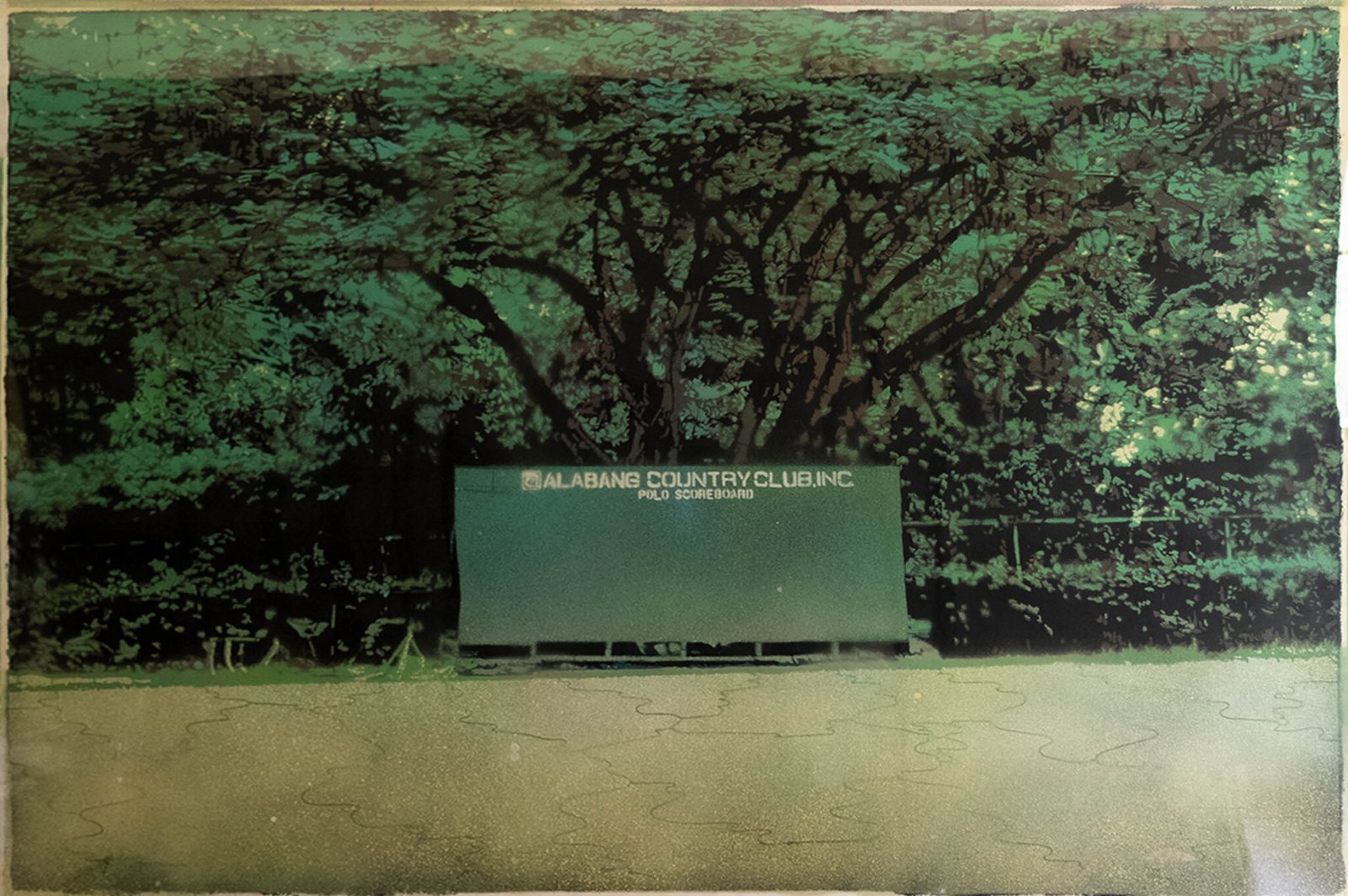

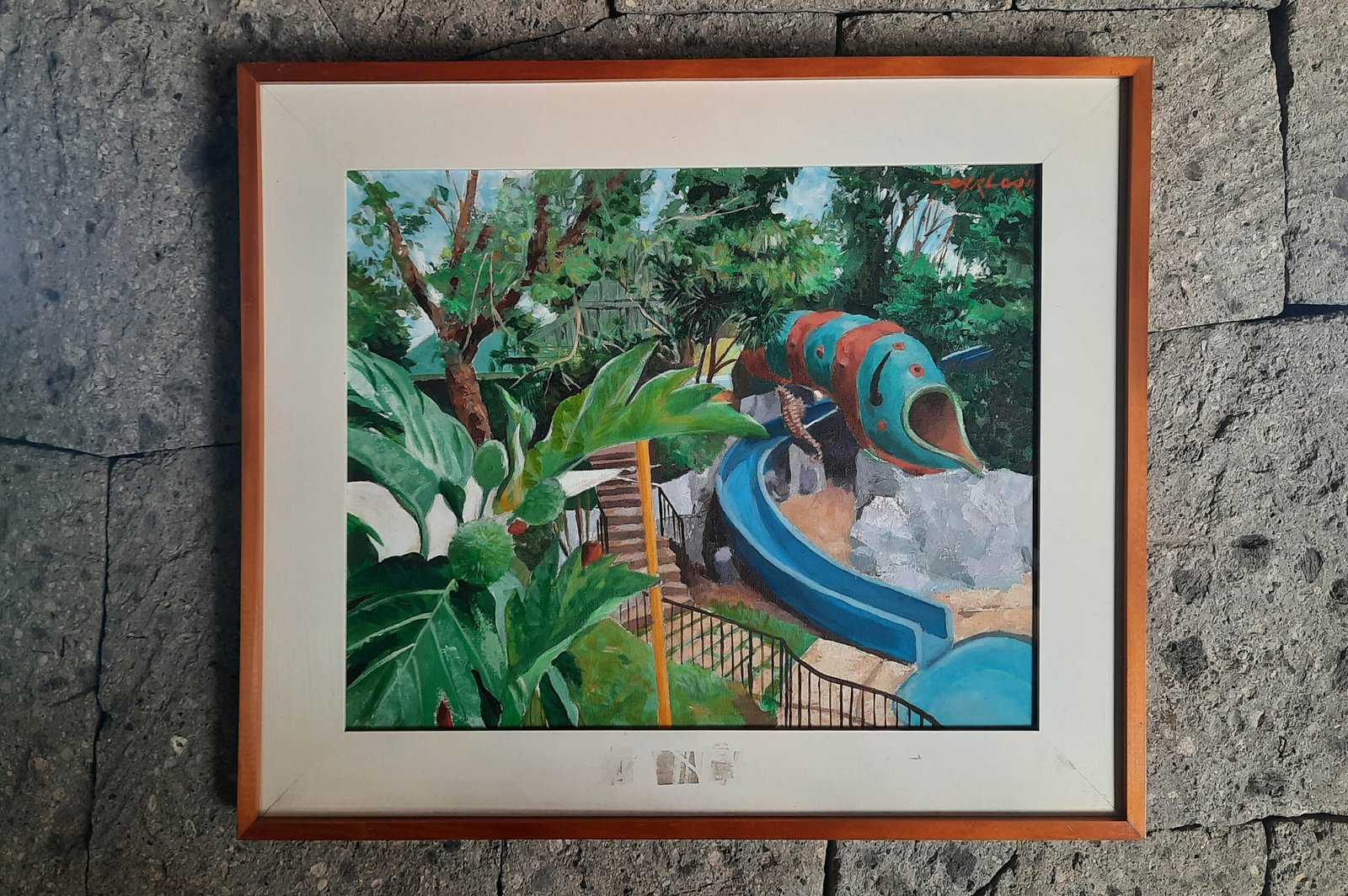

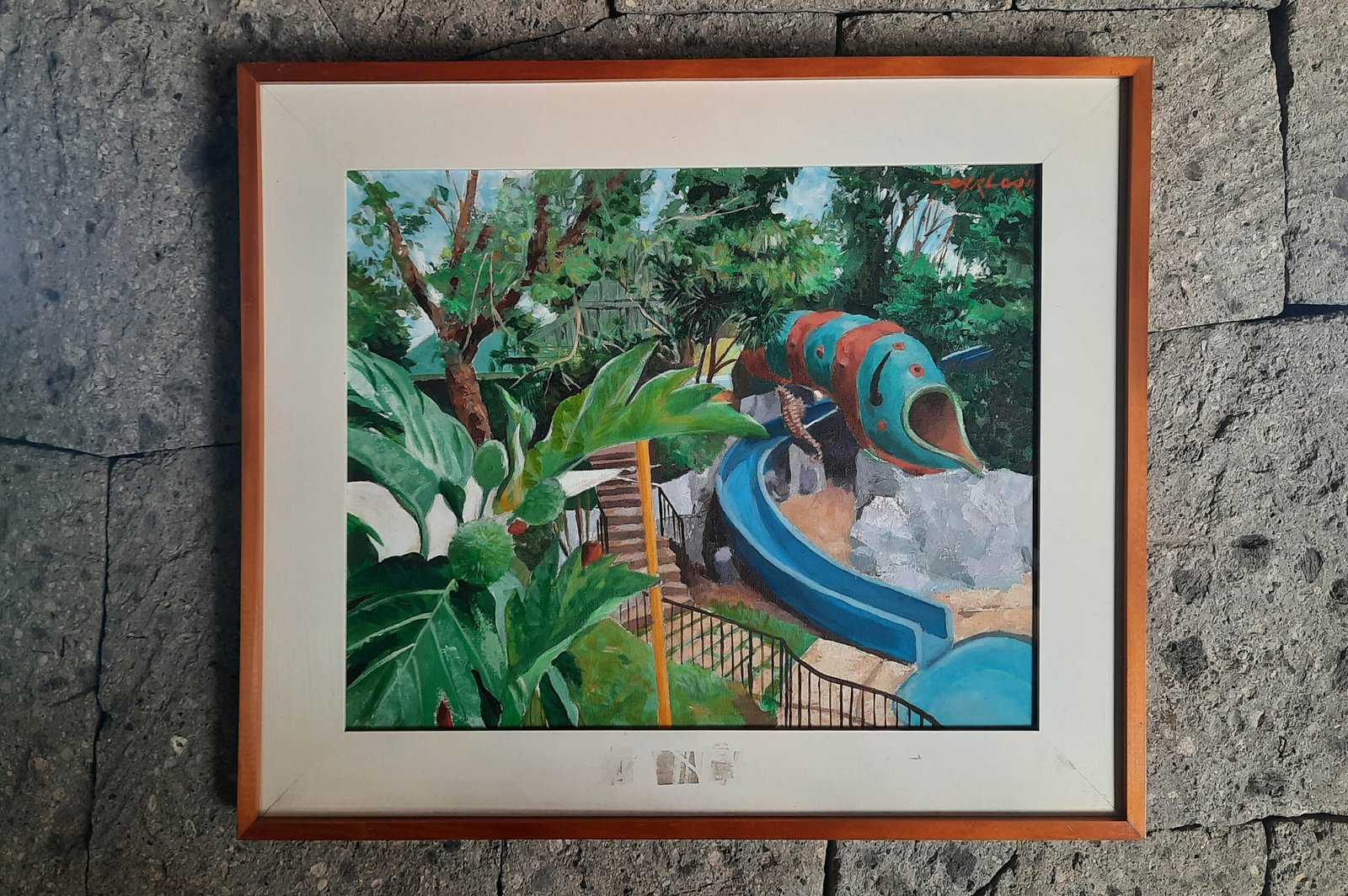

Which brings me to talk about the Alabang Country Club, a place that’s close to home, a childhood and adult haunt. Physical structures and architecture, no matter how sequestered, always play a part in community building. In anticipation of Alabang Country Club’s 50th anniversary of its incorporation in 2028, it is worth noting its cultural dimension and history that have quietly shaped this establishment, a guardian of a community, upholding sports, recreation, and tradition, contained within a realm designed by architect Gabriel Formoso and golfer Trent Jones.

It is uncanny that the institution of the Alabang Country Club resonates with Ver’s works in a Zen sort of way. For while we human beings try to control everything, life is all about embracing imperfections and uncertainty. In the end, we cannot control everything—and a calm realization manifests itself in the understanding that everything is transitory. Ver’s works embody the vanitas concept in art without needing to be literal (eg. an image of a human skull). In the same way, one only needs to walk a few meters in “the club” to find a safe space for contemplation. “The club” is now turning into a point of transition.

As preparations for the upcoming 50th anniversary is about to begin, do undisturbed settings and solitude have an expiration date? The National Cultural Heritage Act of 2008 (and its designation of 50-year-old structures as heritage) comes to mind as the very real shifts brought about by headwinds in real estate and commercialism slowly steer the club away from quieter times. I recall childhood days spent in much greener surrounds, sans the traffic, the noise.

We all long for a time when routine does not exist and where enthusiasm is infectious. The simple things. Like most feelings, a lot is lost when we try to put it into words. When we think of untouched landscapes, it’s a romantic idea, and our longing for this only grows stronger because of our love-hate relationship with man-made environments and progress. I am reminded of a quote by Louise Bourgeois: “Art is restoration: the idea is to repair the damages that are inflicted in life, to make something that is fragmented—which is what fear and anxiety do to a person—into something whole.” •

Joshua Alexander “Joey” Manalo is a classically trained pianist, having navigated through scores on his own from the age of six, eventually taking private lessons and graduating cum laude in 2009 at Rutgers University with a Minor in Music and a Major in Psychology. In 2013, he completed his Masters in Global Entertainment and Music Business at The Berklee College of Music, Valencia Campus. Joey has performed in various master classes and venues, including the Cultural Center of the Philippines, Philam Life Theater, the Manila International Piano Festival, the Fondation Bell’Arte Paris, the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, and the Wiener Musikseminar. Joey currently manages Outlooke Pointe Foundation’s projects and art collection. The non-profit organization was founded by his father, Jesulito Manalo, in 2007 in a bid to support emerging artists and foster creative collaborations “with the vision of utilizing art as a tool for nation-building.”