Interview John Alexis Balaguer

Editing Patrick Kasingsing

Images Philippine Arts in Venice Biennale (Venice Art Biennale 2024)

Artist: Mark Salvatus, image courtesy of NCCA – PAVB

The Philippine Pavilion at the Venice Art Biennale 2024 promises a compelling journey into the mystical and the national, drawing inspiration from the life and words of the revolutionary lay preacher Hermano Puli. Through the lens of Lucban’s rich musical heritage, as represented by the Young Banahaw Orchestra and Babat Orchestra, the pavilion becomes a stage for cultural resonance and historical reflection. Mixed-media artist Mark Salvatus contributes newly commissioned video and installation pieces curated by Carlos Quijon Jr., transforming into a space for contemplating the vitality and mystique of Lucban’s Mount Banahaw and its interconnectedness with the wider cosmos. We grab a quiet moment with the busy collaborators as they share and ruminate on their work for our national participation in this year’s installment of La Biennale.

John Alexis Balaguer: Congratulations on your work for the Philippine Pavilion at the Venice Biennale! While exploring the ethnologies of Mount Banahaw and Lucban, how did you capture the mystical essence of the mountain while respecting the cultural intricacies of the local communities?

Mark Salvatus, artist, Philippine Pavilion at the Venice Art Biennale 2024: I grew up in Lucban, Quezon, at Mount Banahaw’s foot. Because of the treacherous terrain, no communities are living on the mountain itself, although there have been attempts. The mountain’s beauty evokes mystery and danger; as the most visible landmark in town, you are never too near or far from its pull. No one owns Mount Banahaw, but our artistic community has assumed the role of caretaker of the mountain. No one can easily enter the mystical mountain as you’ll need permission. Still, luckily for us, Southern Luzon State University allowed us to explore not only the biodiversity but also the cultural side linked to the peak.

The mountain holds a special significance in inspiring local people, artists, musicians, and filmmakers from Lucban. As someone who wants to study Mount Banahaw, I aim to connect its influence on the many artists from this region. This inquiry is not a one-time project but a lifelong journey to understand my roots and how to navigate my life while being far away. The mysticism and spirit of the mountain play a significant role in this inquiry, as they are intangible concepts that can only be believed in. This idea of belief, similar to sound or music, is something that cannot be grasped but instead travels through the air, creating new imaginations.

The role as caretaker really grounds how you and Carlos might have come into the explorations of space, which is a very interesting way of handling the mystical elements, as well as the local communities around the area.

Salvatus: I believe my respect for the mountain has been passed down to me by my parents and grandfather. My grandfather used to talk about the mountain in his writing and poetry, which sparked my interest. As a child, I was taught that we must take care of the mountain because an ermitaño (hermit) lived there and looked after the town. Being a caretaker of the mountain is not just a physical responsibility, but it can also be an imaginative one through works that can be shared and circulated among people. I like the idea of people using their imagination to take care of the mountain. Local bands have produced music in honor of the mountain, and during the Pahiyas Festival, Mount Banahaw is presented as a guardian, while the people themselves guard the mountain. It’s a mutual relationship where people take care of the mountain, and in return, the mountain takes care of them.

Carlos, Mark mentioned the emerging imaginations stemming from the engagement with the mountain and its surrounding communities, highlighting the concept of a symbiotic relationship, which the exhibition actively explores through various themes such as renewal, environmental challenges, and the transformative power of local imagination. How have you approached curating the Philippine Pavilion to enable these to unfold and engage viewers in a multi-layered experience?

Carlos Quijon, Jr., curator, Philippine Pavilion at the Venice Art Biennale 2024: How can we approach and handle the intricacies and complexity of the national? Mark’s approach is well-suited to dealing with this kind of complexity. It doesn’t focus on Mount Banahaw’s essence or mysticism itself but instead on the collection of things that reference these ideas. This also relates to Mark’s idea of taking care—the mountain takes care of the people, and the people take care of the mountain. Through his work, Mark emphasizes the importance of renewal, addressing environmental challenges, and tapping into the transformative potential of the local imagination.

In preparing for the Philippine Pavilion, we also talked about all kinds of materials: family photos, literature, poetry, film, and popular references like Banahaw massage and Banahaw water. This assemblage offers us a counter-essential way of thinking about the mystic because it proliferates in the lives of the people surrounding it. The concept of ethnoecology is fascinating to me, particularly as a curator, because it is simultaneously about the life of people and their surrounding environment. Regarding the national pavilion, we must consider the complexity and nuances of representing an entire archipelago as a nation. This is where Mark’s practice comes in handy, as his approach to salvaging and assembling collections complements this idea well. There is this coming together of different things and aspects of living and life worlds.

Regarding the curation, I aimed to showcase a sense of openness and an opportunity to encounter mystical elements in the exhibition space. The exhibit intends to encourage viewers to expand their perceptions of the mystical, which can take many forms and be found in many objects.

The mystic then becomes a tool that constellates all these ethnologies, communities, truths and untruths, and all of these ways by which individuals and communities engage with the life world of the mountain.

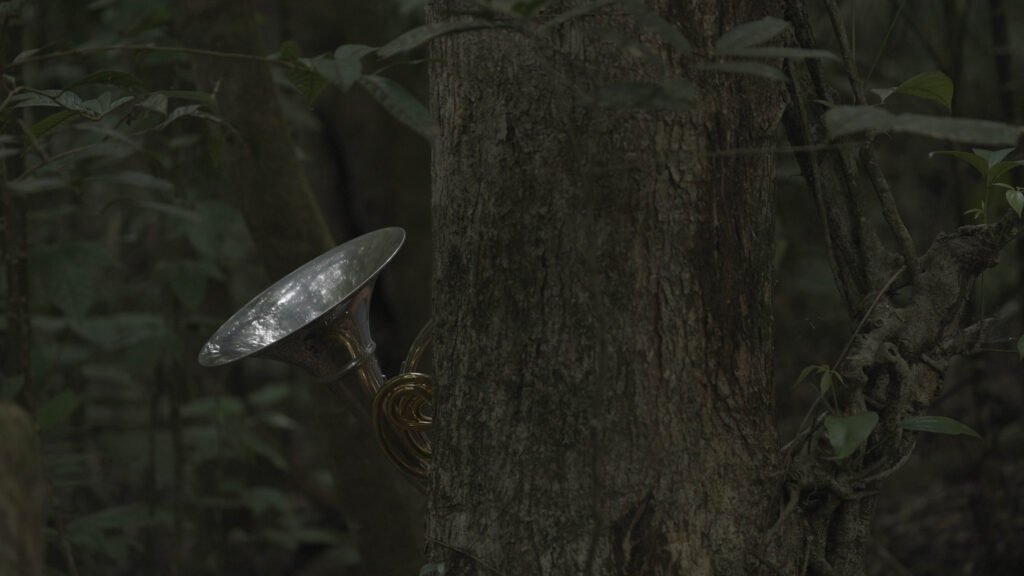

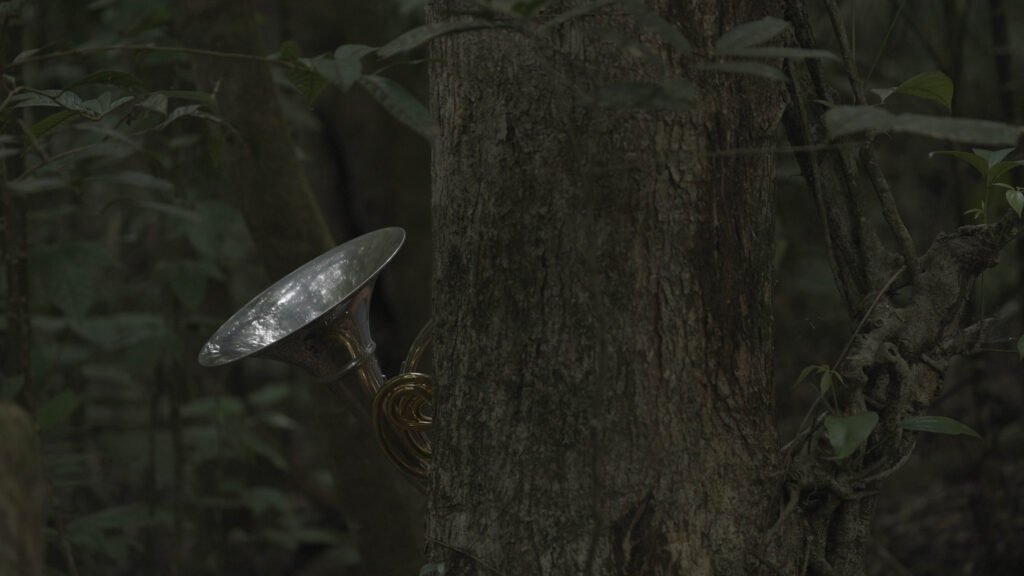

Mark, I wanted to ask about one of the commissioned video work. We see musicians traversing Mount Banahaw and then a subsequent transformation of their instruments into natural elements. How did you find the interaction between nature and culture as you engaged with this particular geography?

Salvatus: The idea of transformation through music is fascinating. Musicians seem to become different people or beings while they play, as if they are releasing something within themselves. This invisible experience is a beautiful way of transforming. Music connects to the concept of transformation, which we also see much of in the environment. For example, living in the countryside and moving to the city can lead to profound transformations.

In my video work, I focus not only on the local area or landscape but also on migration. Although the mountain cannot move, its spirit can move through people in various forms. Even though I am far away, I still feel a connection to the mountain’s spirit, and I think the musicians I work with also feel this connection. It’s a cycle of belonging, a never-ending search for something.

Multiple elements are at play in the Philippine Pavilion’s exploration of sound as a scape. As you mentioned, there are visual and video elements besides the soundscape. Furthermore, other materials, such as textile panels and stone sculptures, were incorporated into the space. How did you envision the audience interacting with these materials within the space, which aims to allow for a transformative experience?

Quijon, Jr.: We wanted the space not to be as burdened as the other spaces because the national pavilion requires the burden of representation: we’re representing our nation-state and our national culture. We wanted the pavilion to be a space of intuition. I think that also ties in with the idea of the mystical. We think about the mystical through a body-affect moment, which is always a concept. It’s not always the mental aptitude; it’s intuitive, something you feel and that the body responds to. We wanted the pavilion to be a space to breathe, parallel to what Banahaw represents—the idea of rest and an open space. So, that’s number one. Secondly, I think one of the things that Mark and I found very interesting in Hermano Puli’s idea of a revolution is that it is a transformation after passing through a curtain. It’s a stage trope metaphor for the revolution as the staging of this kind of passage, and that also shaped our approach to how we imagined the pavilion. This also speaks to the type of artistic practice Mark devotes himself to: collaborative, open, and very intuitive.

When the Philippine Pavilion started to take shape in the conversations, one of the things that we considered was conceiving it as a stage, a theatrical space where people can enter a passage of ‘transformation’ because it’s in the middle of two pavilions that might be responding to the burdens of nationalism or national representation.

So, what if the pavilion is a threshold in thinking about the national in relation to something more intuitive, like the mystic, the mystical, or the mystical qualities of Mount Banahaw? The exhibit will be theatrical in that how people encounter and respond to the works forms part of the pavilion. Interactions will also be part of the artwork because it is a theater stage.

We didn’t thematize the mystical; we tried to recreate and transpose the exhibition space as a mystical space. If the exhibition thrives in this kind of artifice, you collect many things and present them in one space. I think the way Mark also presents the mystical, it’s also that kind of artifice, it’s a collection of things, it’s a collection of family photographs, family archives…it’s a collection of experiences. I think that’s a very compelling way to think about the mystical in relation to an exhibition because the exhibition also works within that logic of intuition, feeling the space, the artwork, and their connections with each other.

So, these are some of the things that we thought about…not necessarily the medium themselves, not necessarily that we need to have sound. It’s how to stage this encounter with the mystical, for the mystical exists not only in relation to objects but also to stories, to things that are not only in the national or the idea of the national but also how these musicians, who have a very particular and unique relationship with the mountain, travel and carry with them this idea, that “I am blessed with this Mountain’s mysticism, this Mountain’s healing powers, this Mountain’s energy and vitality.” So, staging it is one way of letting or transposing this experience for others, the world, in this case, to share in the mystic.

Salvatus: In the first few conversations, we wanted to make a stage, but at the same time, it’s the backstage and the side stage. You don’t know which ‘stage’ it is because a “stage” is already inherently hierarchical. To be on stage is a special position. So, we thought of creating a space wherein you can leisurely walk or traverse. The soundscapes, the objects, which are barriers, and the video can be vantage points of this stage, which we think is an interesting notion of how to create structure or the idea of a space without hierarchy.

When you go to the mountain, I think it’s magical because once you are far away, for example, the vista, wow, it’s so huge, but when you are on it, it’s flat, and you become part of the view. So, we considered this stage a simulation of the ‘everywhere.’ We talk about it as a rehearsal. It’s not the actual play, or it’s not yet the main revolution.

Creating a theatrical or experiential atmosphere through sound, visuals, and moving images can encourage people to sit or walk slower. It is understood that not everyone will stay, as there are many spaces to explore in a limited amount of time. We aim to create an impactful experience while allowing others to share the emotions and feelings we hope to evoke.

The pavilion’s title, “Sa kabila ng tabing lamang sa panahong ito/Waiting just behind the curtain of this age,” is taken from the prophetic words of Puli, a religious leader and revolutionary. It suggests liminality but also anticipation. Can you elaborate on the concept of this zeitgeist?

Quijon, Jr.: The way we think about revolutionary history is how it ends; it’s always what comes out of it. What is interesting about the framing of the title is that it suspends that kind of results-oriented revolutionary discourse because it’s the anticipation, the hope, the promise of something that will change beyond this precipice, just beyond this threshold. It also asks us to think about revolutionary idealisms as promised, hoped for or something that we anticipate. For the idea of a stage, it’s not necessarily that you’re not walking into a finished, formed encounter with the mystical; it’s something that unfolds as you traverse the space.

The notion of a suspended time frame is also interesting to me because it relates to the idea of this pavilion space as a place of rest to catch your breath in this hectic biennale context. Navigating the space also alludes to the passage of the curtain—it’s a threshold. This frame of mind or bodily experience transposes that kind of imagination for hope.

Salvatus: This idea of “behind the curtain” is something abstract, which we want to show in the pavilion. When we think of national representation, it’s always “What is Filipino art?”. Maybe what we are looking for is just behind, but you cannot grasp it: the idea of revolution, the second coming of Christ, the idea of a new government, the idea of a new life is something there, but you cannot yet grasp. When you enter space, the space itself is there, but you are also looking for something else. I talk a lot about migration in my work. It’s like a person looking for somewhere, and that’s the aspiration of many Filipinos. That’s the representation that I also want to incorporate. Although the title is historical, it also suggests a very personal or individual aspect of experiencing.

And how about the two of you? What specifically fuels your aspiration to turn this curtain? For you, Mark, for example, you mentioned how this is, at one level, personal, as this was literally home for some time. And Carlos, you have the burden of representing the national as a curator for the Philippine Pavilion. What drives your own turning of the curtain?

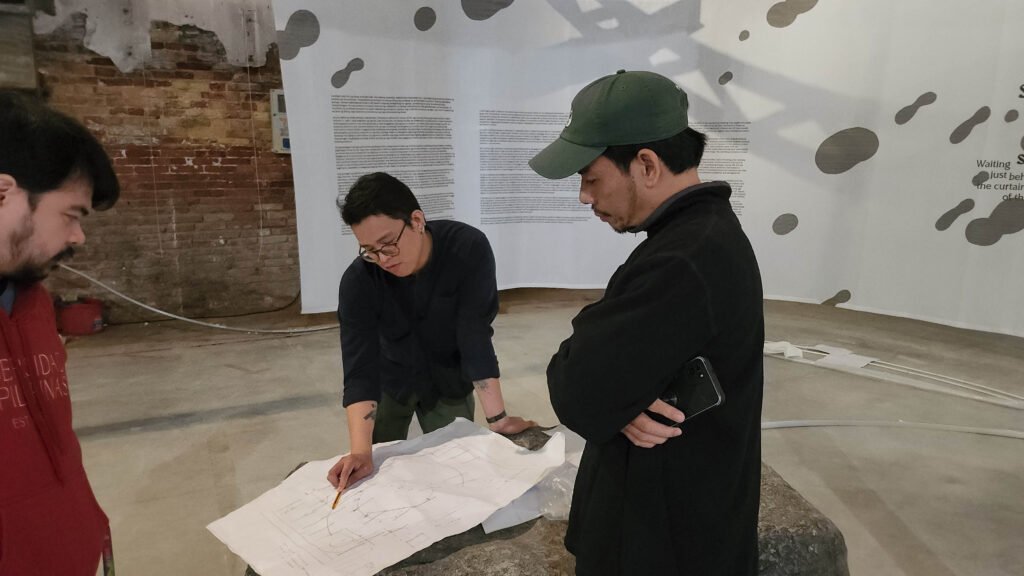

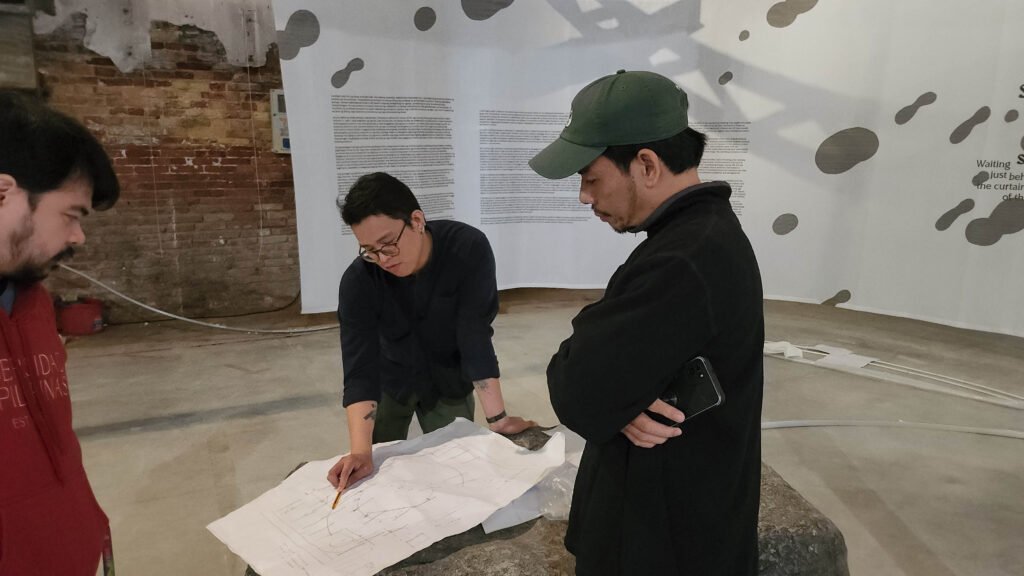

Quijon, Jr.: I am one of the youngest curators to represent the Philippines at the Venice Biennale. When deciding what to present at the biennale, I realized the importance of exploring different perspectives on the concept of national identity, as we are an archipelago with many cultures existing alongside each other. I wanted to think about that through the curatorial process. How should the curatorial be shaped by this kind of proliferation, in terms of the coming together of people, coming together of works, coming together of ideas? I think that’s also what I like about Mark’s practice, that it’s based on that idea of coming together, whether it’s materials or people. Collaboration is essential to exhibition-making since it cannot be done alone.

I wanted to accomplish this complexity in the exhibition so that all of us, the design team, the graphic designer, the musicians that we work with, the people who allowed us to shoot footage on the mountain, and the coordinators, parallel the idea of the national as something necessarily multifaceted. The pavilion itself needs to be complex because it is what it is, a way to think about the complexity of the national, of this archipelago that we call the Philippines.

Once you see the pavilion, you will see how theatrical we went. We did not go with what necessarily worked but made choices that primarily affected the visitor experience. We have textile panels; we have stone sculptures that transform into seats and sculptures that are also speakers. So, the complexity of the nation, the burden of representing that complexity, and representing that in the pavilion is not just conceptual; it’s also material and present in how we collaborated to create the exhibition.

Salvatus: I really enjoyed working with fabricators on this project. It was interesting to me that we didn’t try to make the rocks look realistic. When we think of international exhibitions, they’re usually polished and have a very Western feel to them. However, in Venice, you can still feel the essence of Cubao or Caloocan in the materials used, which is good because that’s how I work. I ground myself in the materials, and the technology used is also grounded in a DIY spirit, especially when working with the instruments. This approach is true to my practice.

Collaborating with others is an essential aspect of my work. It’s no longer just an individual effort but a collective one. The result is an exhibition and a stage or play we all worked on together.

As we prepare for the exhibition in Venice, I’m interested in how we will present our work. Some of the fabricators are concerned with making sure it meets Western standards. However, I also value the imperfections and reject lines characteristic of our work in the Philippines. Even the quality of the video we use varies; it’s not all 4K, as I filmed some using a handheld camera. This creates different perspectives and adds to the overall effect of complexity we are after. By transforming these materials within the context of the exhibition, we can create something unique and distinctive.

Collaboration in curatorial work, art organizations, working with communities, working with people, and listening to them sort of enworlds this biennale experience. It seemingly reflects the starting point, the mystical mountain many communities share. Again, no one owns it, but everyone partakes in it, similar to how we partake in this idea of the nation.

The works, the exhibition, and the curatorial drive engage with all these aspects: the idea of hope, renewal, a liminality, but also a promise, and the local and personal, historical, social, religious, political, and cultural, all constellating into this particular world. Even so, we come back to the idea of home, home being Lucban, Banahaw, or the Philippines. To end, how do you envision the trajectory of the pavilion exhibition shaping a broader worldview?

Quijon, Jr.: What sets this exhibition apart from previous pavilions is how we approached the topic of home and nation, aiming to capture their complexity as accurately as possible. The national is present in the exhibition, as are the questions surrounding it. I feel that it’s the best way to represent the nation. I think what the pavilion allows us, especially cultural practitioners in general, is the space to think about the national in relation to other things. The kind of experience that we want to happen or to unfold in the Philippine pavilion this year is for that complexity to have room for everyone.

For example, the idea of the mystical and the intuitive. Many people will not know what Banahaw is or what Banahaw represents. In this exhibition, we wanted to stage that kind of relationship with the ethnos and ecology. Now, it’s the life of a people. It’s also an ecological context, a planetary context, for many planetary meanings because Banahaw isn’t only about the Catholic religious strand. It’s also about how you can frame it in relation to climate catastrophe. You can frame it in relation to UFOs and the extraterrestrial. So, I think that’s something that we want the exhibition to accomplish, that the idea of communicating the national is complex. Necessarily representing the nation also requires asking more things about the nation. The national also includes things that are not necessarily national under the term of the national. It also exists alongside other nations, so it’s also international. Through this exhibition, we wanted to flesh out these layers, an entry point to understanding what the national entails and how we can work with it as a concept.

It’s not a critique or a naive embrace of the national. It’s something in between.

And, Mark? How do you see the trajectory of this exhibition, maybe not simply as a worldview but as a cosmos or from a universal dimension? Perhaps worldview is a limited view in the discourse of the extraterrestrial. How do you see this exhibition contributing to that discourse or potentiality?

Salvatus: Interestingly, communities near Banahaw stage UFO dances like a pop culture festival. And in that essence, they already thought of something beyond the Earth or something of another world, beyond our life here. And this is interesting because we are experiencing different environmental catastrophes. Lucban is one of these protected sites. There are also various stories that Banahaw was said to have been a site for UFOs to refuel in the ’90s. These stories prevailed around the same time the government transitioned after People Power. Looking into the UFO sightings, maybe it was a tool to divert attention.

I’m fascinated with this interconnectivity of different stories and how people create their imaginings about the future and elsewhere. And I guess, with this exhibition, it’s this aspiration that we can be everywhere or that we can also be someone else in this context of survival. And it’s also beyond movement, as surviving also tends to create this idea of adaptability. So, in this exhibition, as a space to gather, we can imagine together how to survive, thinking about ways to live together. The mountain is already a place where certain groups of people attempt to live and thrive, like the different religious sects or the Communist party; they all try to use the mountain as a place to live. But there are also other ways to gather and be together, to survive together. Our Philippine Pavilion will not be the answer, but I think it is there, so we have a venue to imagine together; maybe imagination is what we lack now. Perhaps it’s something that we should try to do together: to imagine together so we can appreciate how we can live together. •

The Philippine Pavilion will be open from April 20 to November 24, 2024 at the Arsenale in Venice, Italy.

John Alexis Balaguer is a Manila-based curator, critic, and cultural worker teaching Fine Arts at the University of the Philippines. Balaguer worked as Curatorial Researcher at Ayala Museum and Gallery Manager at Archivo 1984. He founded Curare Art Space, contributed reviews to Kanto and ArtAsiaPacific, and penned curatorial texts for art galleries in Manila. He was recently selected to participate in the 2024 Writers-in-Residence art writing residency hosted by the Salzburger Kunstverein (Salzburg Art Association) in Salzburg, Austria.