Words and Images Rhea and Gabriel Schmid (Western Bicutan Tenement)

Editor’s Note: This piece was co-authored by siblings Rhea and Gabriel Schmid as “The Tenement: A Territory and an Unexpected Oasis; When Brutalist Housing meets a Collective Culture.” Kanto.PH crafted a new title and subhead for editorial purposes, with minor edits made on the article for brevity. Below is a note from the authors:

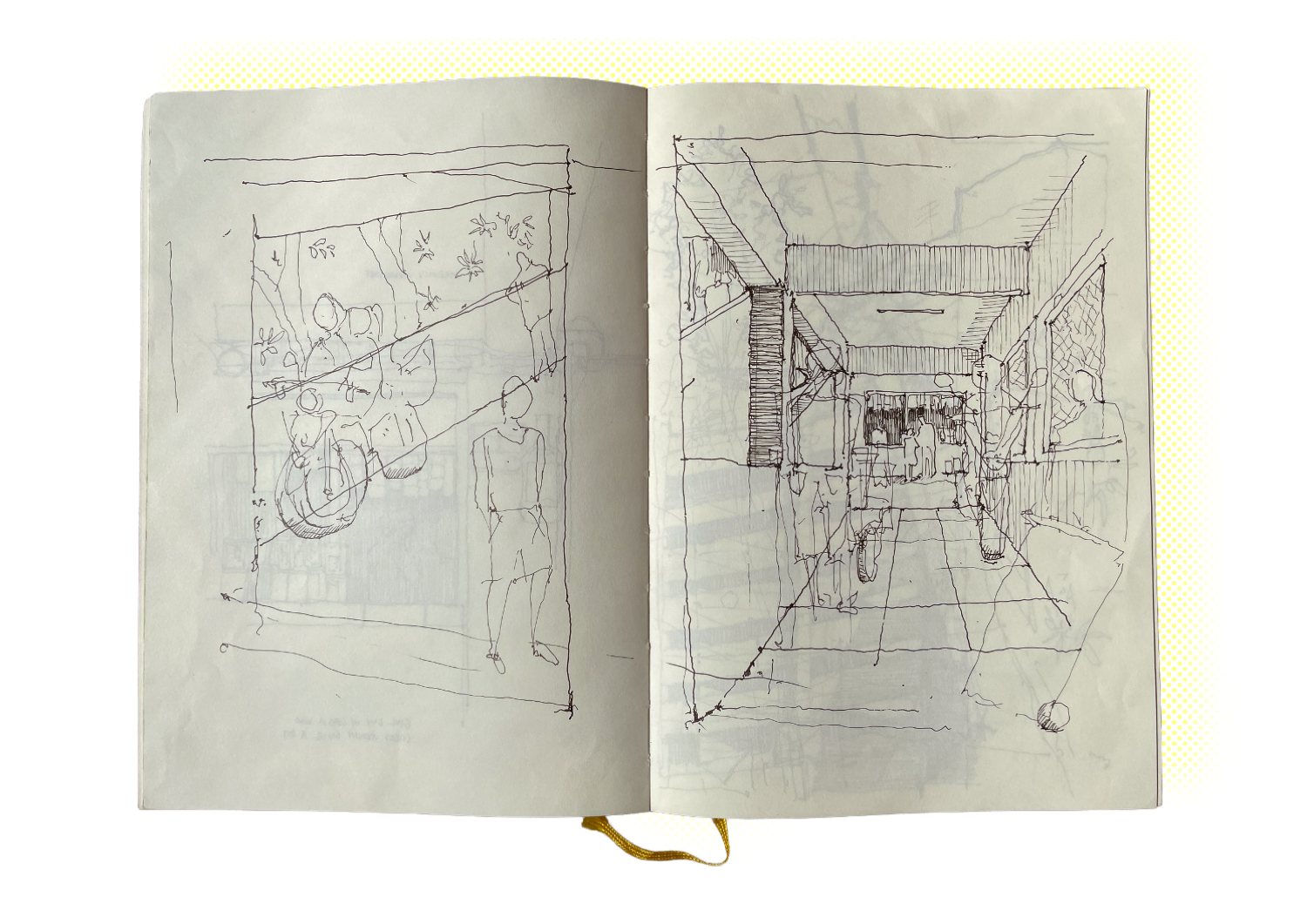

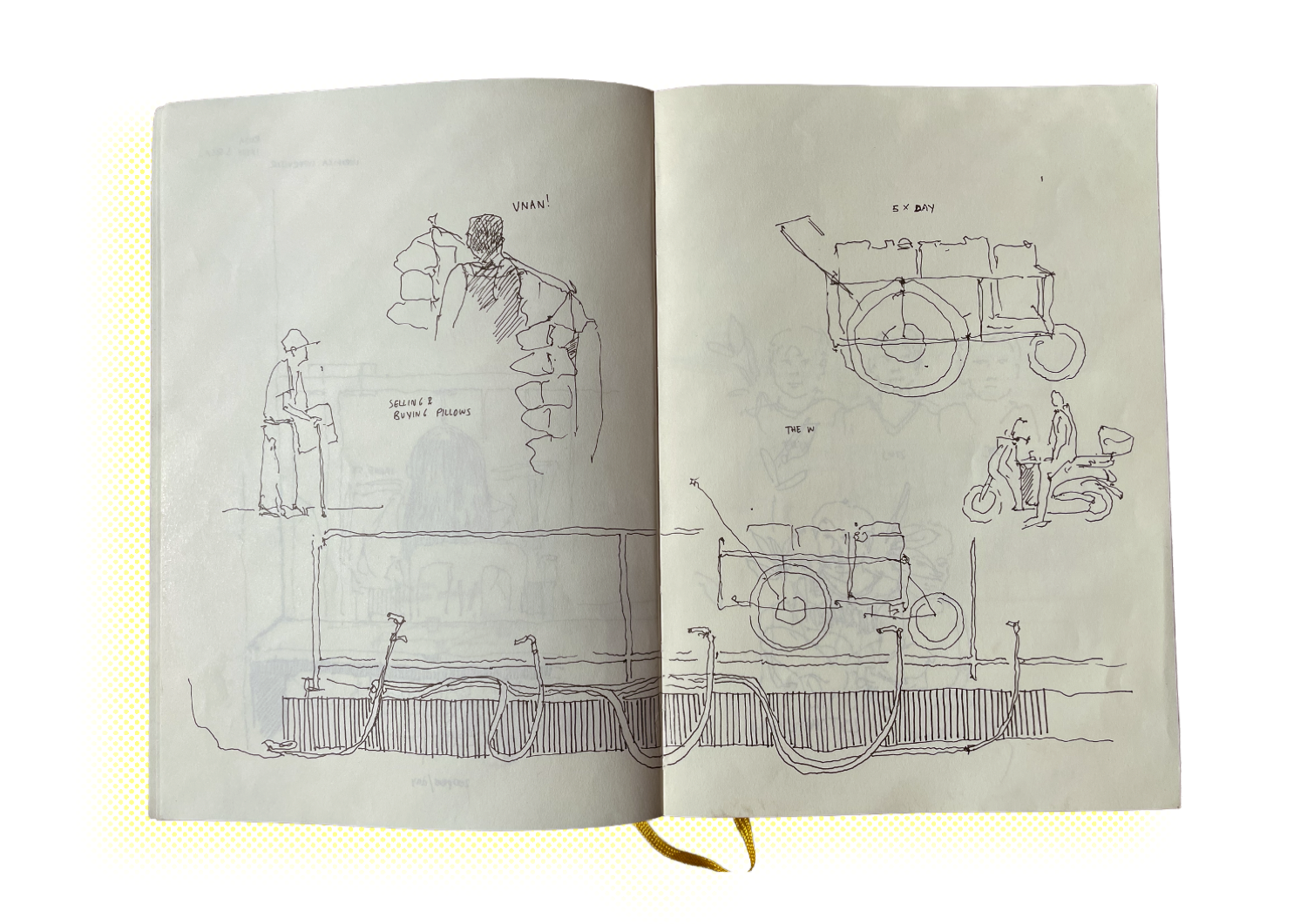

Both immersed in the world of architecture, Rhea and Gabriel like to think about the relationships between space and community, and have developed an appreciation for the Western Bicutan Tenement. Gabriel grounded his architectural thesis in this social housing project, while Rhea has spent significant time simply being there—observing, meeting, and drawing. Through their combined perspectives, shaped by architectural analysis and lived experience, they explore how this building reveals its meaning not just in form, but in the lives it supports. All visual content, including photographs, sketches, and artworks, was created by the authors.

The Manila heat can be relentless. The air hangs heavy with humidity and smog as we drive through a sea of one- to two-story buildings toward a large concrete structure. Like a massive, abandoned ship caught in rough waters, the building’s exterior is battered, weathered, and worn. On one side, we scale the length of the 150-meter-long, seven-story-high facade, and on the other, we pass a row of small food stalls crowded with people, spilling onto the street, dodging the slow traffic. We turn the corner and park just outside the entrance to the Tenement.

The Western Bicutan Tenement stands as a unique fixture within the dense and layered urban landscape of Metro Manila—a sprawling conurbation of sixteen cities shaped by centuries of colonial rule, waves of rural-to-urban migration, and the complex pressures of privatized urban growth. Manila’s urban form reflects 350 years of Spanish colonization, 50 years of American occupation, the devastation of World War II, and successive waves of speculative development that have challenged public planning and oversight capacities. Within this fractured metropolis and its persistent housing crisis, the Tenement offers something remarkable.

Inside, the atmosphere is palpably different from the congestion just beyond its walls and deteriorating exterior surfaces. The inside is calm and alive. Paint covers the walls wherever paint rollers could reach, bringing an inviting dynamism to the concrete surfaces. Though wide hallways that double as balconies are covered with plants, lights, posters, and laundry, it doesn’t feel messy. Light spills in from above, and shadows cut through the wide space into the courtyard. There’s a tree in the middle of the courtyard, perhaps a Dita.

Stepping into the Western Bicutan Tenement feels like stepping into another world. As a few kids practice their three-pointers on the basketball court, others rally across a badminton net, and a couple of men sit in the shade, playing chess.

“I’m from the housing project across the street,” one of them says. “It’s not as hot here.” He moves his black knight to a white square. Check.

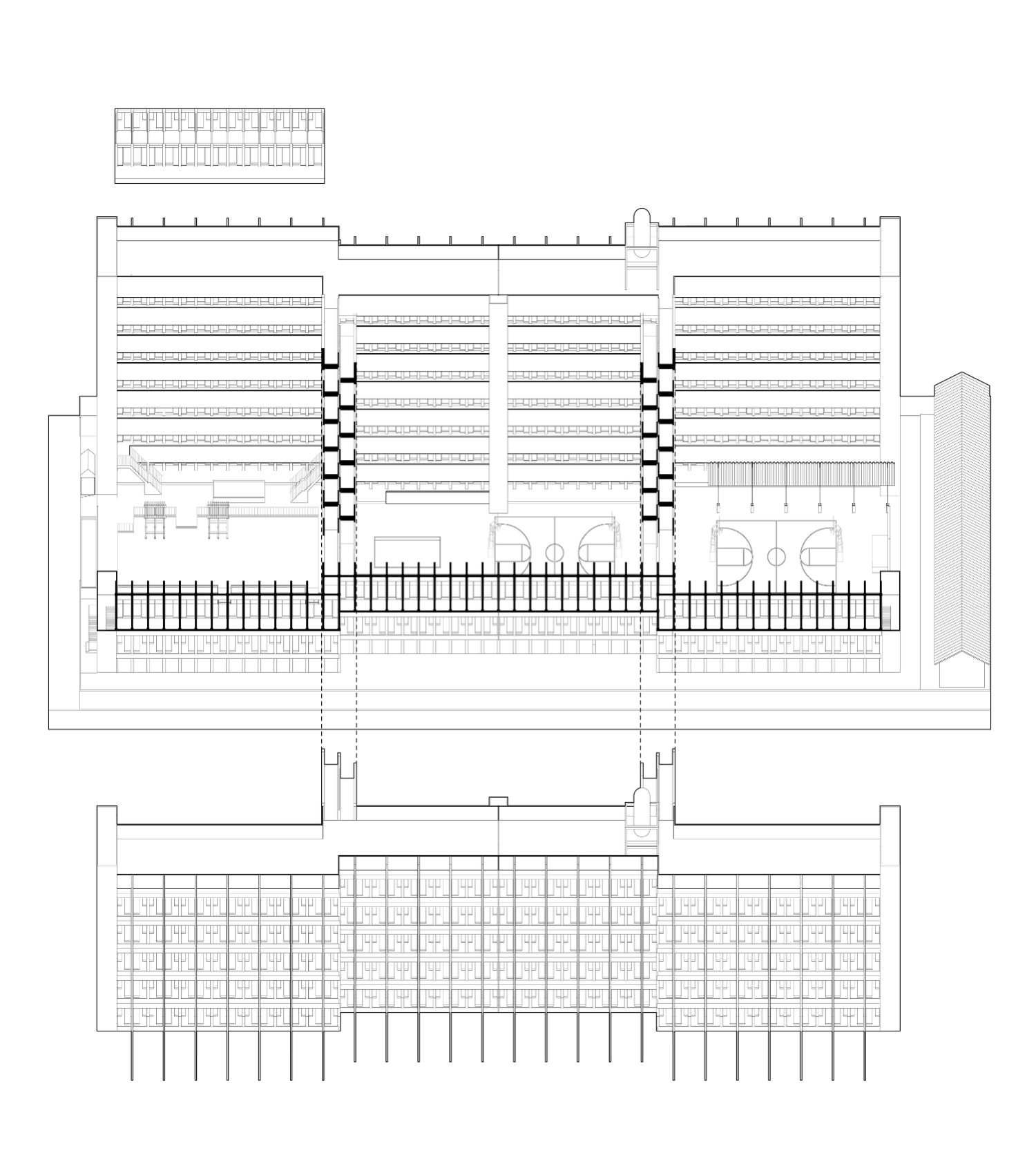

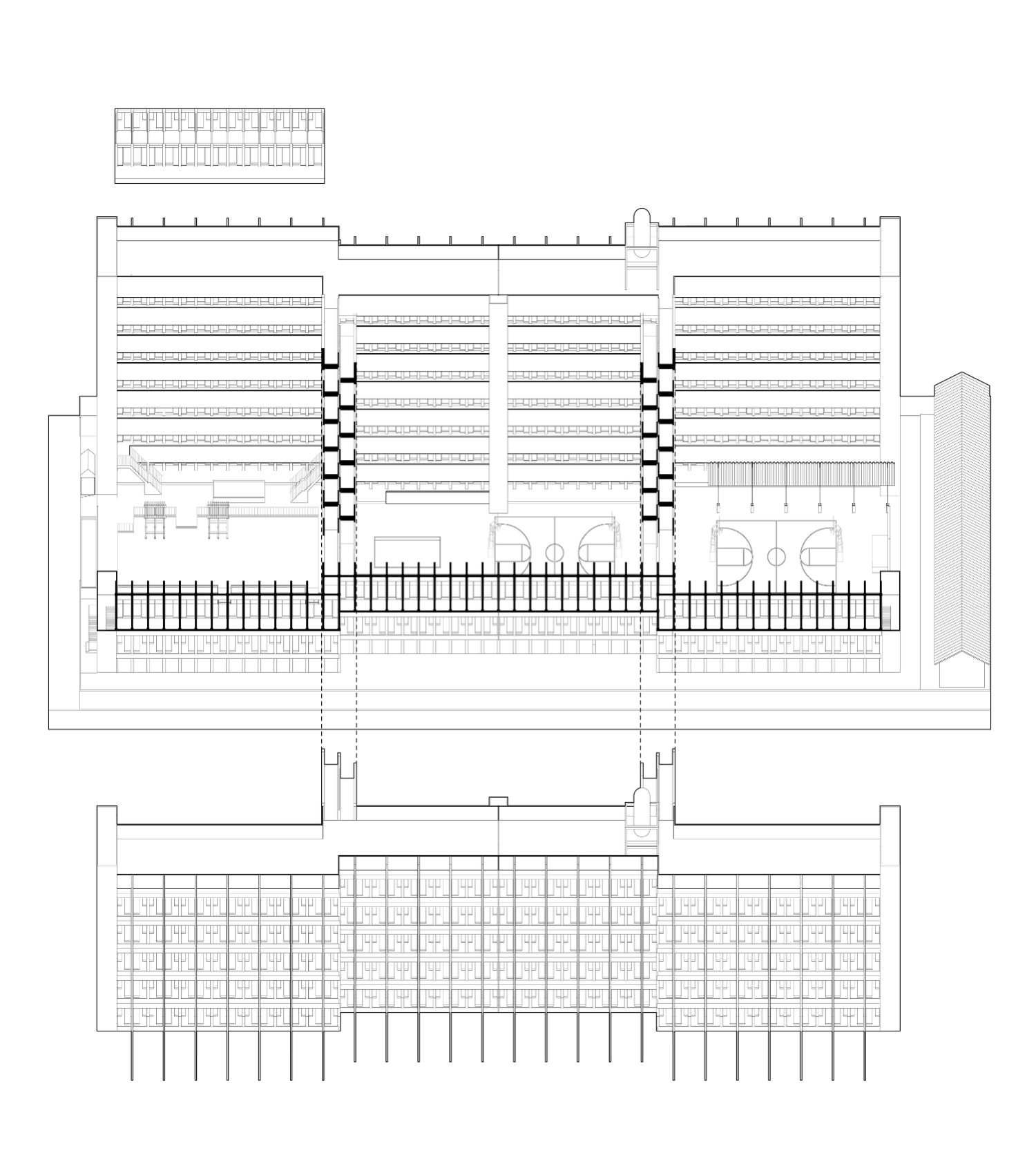

Built in 1963 to rehouse 720 families from nearby informal settlements, the Tenement is a postwar housing project that still stands more than six decades after its completion. The concrete mass consists of two long housing bars connected by two ever-buzzing ramps that flank a shared central courtyard. Each 20-square-meter unit is cross-ventilated with windows on each end of the room. The ground floor, including the space around the courts, has self-organized into overlapping zones for sports, performance, and play. Even a clinic, a community center, and a chapel organically emerged from what was once conceived as only housing. The ramps function like vertical highways, while the courtyard provides a central space for fiestas, congregations, and games. In recent years, the basketball court has gained media attention, serving as a physical platform for public art and community expression, most notably a mural honoring Kobe and Gianna Bryant after their passing.

Motorcycles, trolleys, and residents pushing carts with water containers move up and down the inclined ramps. Most residents haul water up to five times a day, as the municipal water supply doesn’t generate enough pressure to reach the upper floors, leaving them no choice but to carry it by hand. One woman in her sixties, lifting a full container onto her trolley with a laugh, chose to focus on the good: “It keeps me really fit.”

Halfway up the ramp system, we glance over to our sides, the Tenement sandwiched between framed skies and the defined court. Overhead, clouds glide by as children below bounce balls in their flip-flops, the steady and sporadic thump-thump reverberating through the open space. You can barely hear Manila in the distance, though just on the other side of the walls.

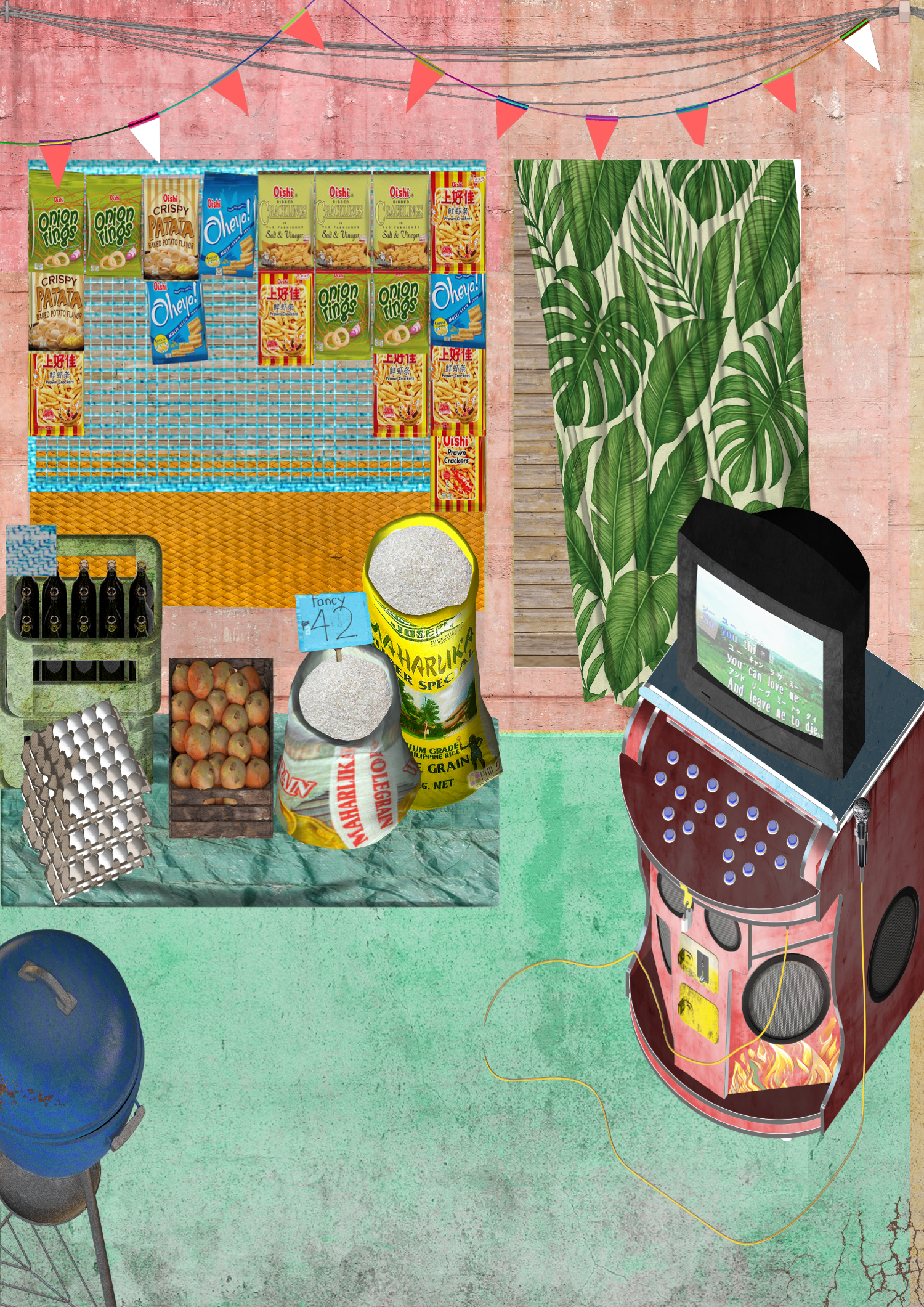

Activity extends along the wide walkways and ramps to the top, which not only serve as circulation but also function as active community and retail spaces, supporting resident-run barbershops, food stalls, internet cafés, and sari-sari stores. All of this exists within the Tenement walls, forming a clearly defined and protected world. From the rooftop, Metro Manila unfolds in every direction, no end to its sprawling madness. The density surrounding the project is striking. It feels like standing at the edge of a vessel, where the towering skylines of Makati and BGC, two of the city’s main business districts, loom in the distance like oncoming waves.

There is much to critique, including visible strains in infrastructure and municipal services, such as inconsistent water access. And yet, life fills the space with a sense of pride and dignity deeply connected to the building itself. This sense isn’t just felt but was also communicated to us by multiple residents. AC Catacutan, a student at Taguig University, describes the Tenement community as united, caring, and resilient. People are proud to be part of this community; they are proud of the Tenement. And their pride seems to spring from acts of care. “It feels like home because everyone looks out for each other, and I believe many of us feel the same way because we’ve gone through a lot together.” The residents of the Tenement are no strangers to fighting for their rights to be there. In response to an eviction order by the National Housing Authority in 2014, the community rallied, hanging protest posters while standing their ground. They won.

Catacutan reflects on how the Tenement is perceived: “Some see it as a tough place, but those who know it well respect the strong spirit and unity of the people who live here.”

“The Tenement is a territory, an unexpected oasis. It feels like the eye of a typhoon too.”

Originally managed by the city, the Tenement is now overseen by a homeowners’ association that coordinates building maintenance, community events, and security. Crucially, many descendants of the original residents still live here, fostering a strong sense of continuity and belonging across generations.

Its success contrasts sharply with similar projects abroad. Take the Robin Hood Gardens designed by Alison and Peter Smithson in 1972 in Poplar, London, for example. By internalizing public space, the Smithsons hoped to promote a sense of shared responsibility and inspire healthy communal living. Unfortunately, their vision never materialized. Poor maintenance and systemic socio-economic inequality undermined their intentions. High crime and vandalism—the very behaviors that the Smithsons believed their architecture would mitigate—directly contributed to its eventual demolition. This highlights how cultural norms, values, location, and community cohesion shape the long-term viability of brutalist social housing. It hardly works in reverse. Architecture cannot transform attitudes, but it can shape what’s already there. The Western Bicutan Tenement stands as a testament to self-determined, community-centric ways core to Filipino culture. The building provides the structure, but it’s up to the community to breathe life into it.

Architecture often aims to create a sense of harmony as imposed from the outside. Design will always involve a degree of imposition. But if it can assert itself as a part of an ongoing dialogue, it opens the possibility for harmony and belonging to emerge organically, directed by those who inhabit the space. The challenge lies in finding a balance where design asserts itself with enough clarity to guide, and with enough humility to allow life to take shape around it. Ironically, in the context of the Western Bicutan Tenement, a brutalist building, often interpreted as harsh or unfeeling, strikes this balance.

This requires intentionally leaving room for organic growth and adaptation. For example, each unit is left for the residents to make their own, allowing personal tastes to coexist alongside the rigid concrete. It is not only about producing a finished product, but about creating an opening where community life can take root and evolve. Is the Tenement an example of people participating in architecture? Beyond material durability, isn’t the community’s relationship to the building the true test of sustainability?

When the built environment unintentionally fragments people, it is easy to point at the people and fault them for their fragmentation. However, if we’ve learned anything about Pinoy Pride, it is that it contains a beautifully stubborn and trusting belief that wholeness—that shared something-something—exists, even when the world around looks fragmented and polarized. The residents of the Tenement, given the space to work together, get to practice this belief every day. We see this in how the Tenement community has self-organized, persisted, and created meaning. So, what then is architecture’s role in supporting collective communities within urban contexts?

Architecture shapes space. It shapes how people meet the physical world as it is. At its core, architecture is a protective act, a series of variations on shelter. It keeps us dry. Keeps us warm or cool. Keeps us safe. It keeps out, it keeps in. It offers stability, durability, and a steady presence that supports those nearby, especially those safely within its walls.

Physically and psychologically, it says: Here, you are allowed. Here, you belong. There is space for you and yours.

If social architecture can offer shelter as well as protection, then we must be clear-eyed about the forces the most vulnerable are up against. Architecture may not be able to change these conditions, but its physical presence can help buffer against them. In the past, the primary threats were environmental: storms, heat, and rain. Today, the more pressing forces often come from within the systems themselves – institutional limitations, uneven development, and a long urban history marked by rupture and inequality. These overlapping pressures have produced a fractured metropolis and a housing crisis that has persisted for over a century.

An anomaly within the fragmented, market-driven housing models that prioritize short-term gains over long-term social integration, the Tenement affirms every citizen’s right to safe, dignified shelter within a meaningful and connected whole. It offers a quiet counterpoint to urban patterns that have often led to physical and social disconnection, and instead presents architecture as a form of physical protection, a formal, dignified structure through which local culture and collective experience can take root and grow without unnecessary interference.

This kind of architecture is both resilient and generative: an accidental armor, a supportive trellis, and a public platform. It provides shelter and stability while making space for openness and change. Rather than imitating collective living, it enables and strengthens it, meeting essential human needs for security, continuity, and belonging—conditions that allow life not just to survive, but to thrive.

“I wish people knew that it’s more than just buildings,” Catacutan shared. “It’s a home full of life, stories, and strong community bonds.” •

Historical and Statistical Claims

- The specific details about Manila’s urban development (“350 years of Spanish colonization, 50 years of American occupation”)

- Claims about Metro Manila being “sixteen cities” and the housing crisis persisting “for over a century”

- The building housing “720 families” and being completed “more than six decades” ago

Comparative Analysis

- The entire section about Robin Hood Gardens needs proper citations – the architects’ names, completion date (1972), location, and the claims about its failure and demolition

- The assertion that this represents a broader pattern of how “similar projects abroad” have failed

Theoretical Framework

- The discussion of brutalist architecture’s social intentions and outcomes

- Claims about how “cultural norms, values, location, and community cohesion shape the long-term viability of brutalist social housing”

Policy and Governance

- The 2014 eviction order by the National Housing Authority and the community’s successful resistance

- Details about the transition from city management to homeowners association oversight

Broader Urban Planning Context

- Assertions about “market-driven housing models” and their shortcomings

- Claims about Manila’s “fractured metropolis” and development patterns

References

Smithson, Alison. The Charged Void: Architecture. New York: Monacelli Press, 2001.

Porio, E. (2009). Urban Transition, Poverty, and Development in the Philippines: A Preliminary Draft. UNRISD Research Paper.

ABS-CBN News. (2020, January 27). PH mural pays tribute to Kobe Bryant, daughter Gianna. https://news.abs-cbn.com

Smithson, A., & Smithson, P. (1972). Ordinary Architecture. Architectural Design.

2 Responses

I was so amazed and happy with what I read because all the lives, stories, and photos taken truly have important stories in the lives of those who lived in the tenement building. I am also happy that I was also part of their research because I was able to share with them our lives in our little home. Thank you very much, first of all to ate Rhea because I am happy that I met her when we first met and became friends. thankyou very much ate Rhea!🥰🫶🏻💗