Interview Patrick Kasingsing

Images Br. Béla Lányi

Open book

It was in 2013 when Br. Béla Lányi, SVD, a Hungarian architecture instructor at the University of San Carlos (USC) Cebu, found himself coaching a group of students for the Student Charette at the World Architecture Festival in Singapore. Their team, alongside noted Cebuano architects Alex Medalla and Buck Sia, went on to win the Grand Prize, becoming world champions. This victory marked a pivotal moment for Br. Béla, not only for the win but for the connections he made with progressive, forward-thinking architects—what he calls “architectural communicators.” These individuals were not just focused on design but were actively engaging in dialogue about architecture’s evolving role in society, both locally and globally.

This exposure, combined with his leadership roles at the University of San Carlos, laid the foundation for Br. Béla’s deeper engagement with the Philippine architectural community. As editor-in-chief of Lantawan magazine and later as chair of USC’s Department of Architecture, he immersed himself in the task of documenting and understanding the country’s architectural landscape. His research, especially his deep dive into the history and influence of BluPrint magazine under the leadership of Judith Torres, highlighted the power of media in shaping architectural discourse.

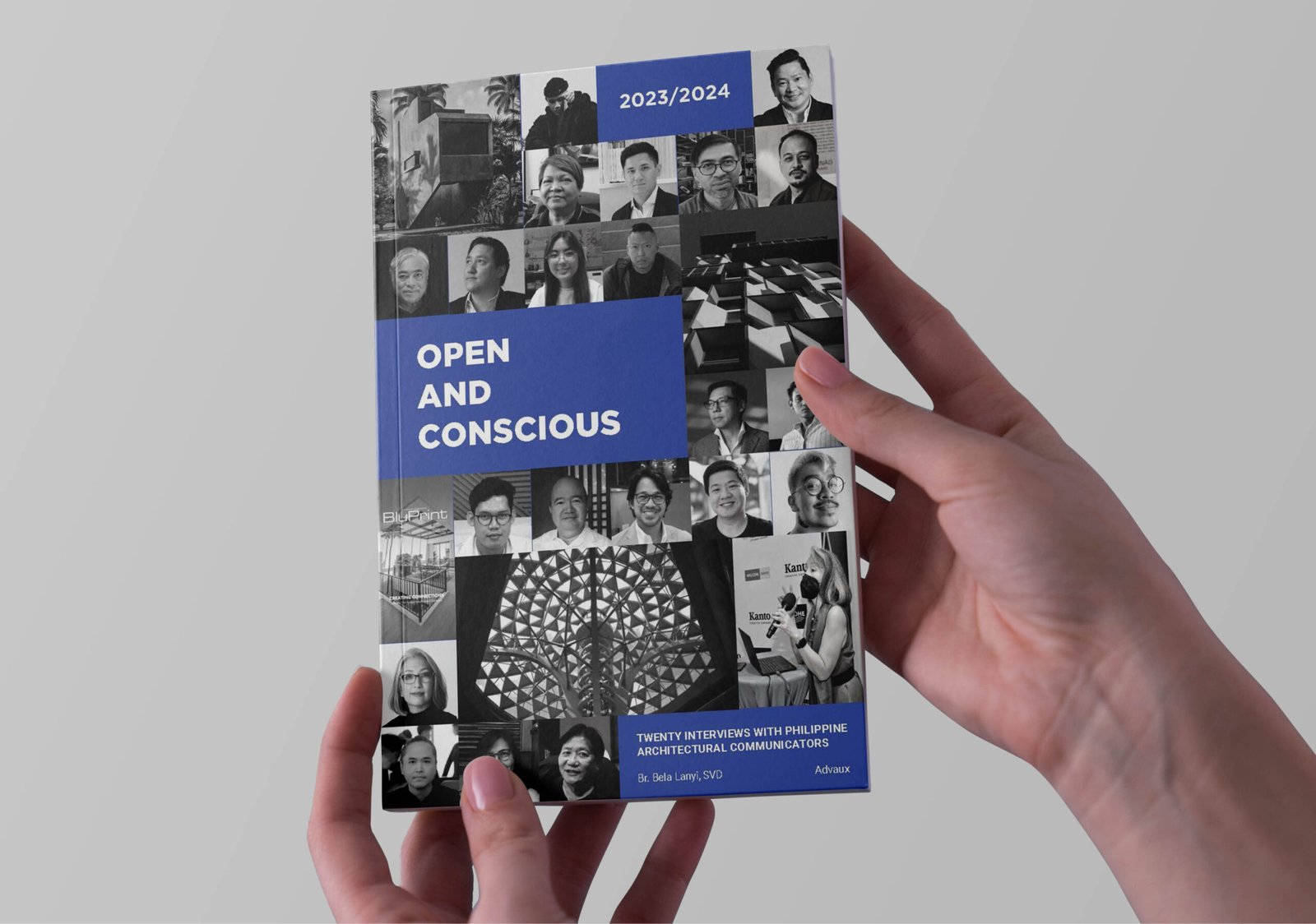

It was this blend of academic rigor, first-hand experience, and an eagerness to bring new voices into the conversation that inspired Br. Béla to compile his first interview book, Heroes and Laborers (USC Press, 2018), and now his second volume, Open and Conscious (Advaux, 2024). This latest collection continues his exploration of architectural communication by capturing the thoughts and experiences of those shaping the field today. In this interview, Br. Béla shares insights into the creation of his book and reflects on the evolving dynamics of architectural dialogue in the Philippines.

Editor’s note: Patrick Kasingsing, interviewer and editor-in-chief of Kanto.PH, as well as former creative director of BluPrint magazine, has been featured in both volumes.

Good day, Bro. Bela! Welcome to Kanto. It is my turn to be your interviewer! You’ve given us a background on the impetus for your two books. Can you now let us in on your selection process on which architects and thought leaders to interview for Open and Conscious

Br. Béla Lányi, SVD, author of Open and Conscious: Hello, Patrick, and thanks for having me! First and foremost, Open and Conscious serves as a documentation of Philippine architectural communication during 2023-2024. I chose interviewees based on their presence in leading architectural media outlets like BluPrint and Kanto. Other Philippine architectural publications tend to cater to more specialized or academic audiences or focus heavily on technical and advertising content. This means the pool of active architectural communicators is relatively small, allowing me to cover almost all of them in this book. Some individuals who were once active communicators have since faded from the scene, so I couldn’t include them. Just to clarify, this is not a ranking of designs or designers; I have no authority or interest in acting as a judge or evaluator, nor is this about representation based on region, gender, or race.

Let’s dwell a little bit more on that. Some may argue that certain geographic regions or age groups underrepresented in this book may also have valid points to share. What are your thoughts on that?

It is not my intention to summarily exclude anyone, of course. However, if the ideas and thoughts of certain individuals aren’t being circulated or discussed today, I didn’t include them as this book is a survey on effective architectural communication. Some attribute this to perceived shortcomings of BluPrint and Kanto, such as their focus on metropolitan areas in the country. While that may be unfortunate, I can’t feature personalities who aren’t active in architectural discourse or whose views aren’t reaching a wider audience.

That said, this documentation shows growing inclusivity in Philippine architecture, with more regions and voices entering the conversation. For instance, this second book includes two communicators from Baguio. Notably, the launch took place in Tagum, Mindanao, during the first Philippine Architecture and Allied Arts Festival (PAAF). Increasingly, national and international events are seeing participation from previously underrepresented areas. I believe that by the next book, these regions will play a larger role, and new architectural media will likely emerge from these far-flung areas.

I should also mention that “architectural influencers” are not included in this book. Their mode of communication is distinct from those whose thoughts are disseminated through formal media. If this second book is well-received, I plan to dedicate my next project to these influencers.

Interesting. Could you elaborate on the differences between their mode of communication and that of the thought leaders you’ve featured? Do you think they could help fill the gap in underrepresented voices?

Yes, their communication style stands out because they often blend education with entertainment, sometimes incorporating humor. This approach can make architecture more accessible to the public, but it can also lead to misconceptions about the field. I’m keen to explore this further. If this second book is well-received, I plan to focus my next project on these influencers, as I believe they can play a significant role in highlighting more diverse voices.

Let’s shift to the topic of architectural communication. In your years of study on this subject, have you found a link between good architectural communicators and better designers?

That’s an interesting question. I want to clarify that this book doesn’t focus on design quality or ranking individual designers. Architecture is highly competitive, and even lesser-known designers can have standout ideas. In fact, many leading architectural theorists aren’t practicing architects, and sometimes, it’s beneficial for critics to be outside the profession. This distance can prevent their comments from seeming self-serving, allowing for a more honest critique.

The book takes a conversational approach to architectural discourse, making it refreshing and accessible compared to more rigorous academic texts. What informed your approach to the book’s voice, and how does this carry over from your first to your second book? What do you hope it adds to the reader’s experience? Lastly, how do the two interview compilations differ from each other?

Architecture is deeply personal. When we commission an architect, we engage with their personality; it’s an art form where technical solutions serve as just the foundation. This is why listening to architects and understanding their perspectives is crucial, as it’s often the key to excellent design.

Architectural interview books are more common in Europe and America, and they inspired me to express the implicit thoughts of Philippine architects explicitly. My first book captured the Philippine architectural landscape from 2015 to 2016, providing a foundational snapshot for theoretical reflection in the field. Over the past seven years, I’ve observed how the discourse has matured, leading to what I now describe as a more “open and conscious” architectural scenario.

This genre allows readers to engage on multiple levels. Some may find practical solutions to everyday challenges, while researchers might explore deeper meanings that align with academic theories. In contrast, the second book builds on this by incorporating new voices and perspectives that reflect recent developments in the field. For example, it highlights more regional contributors and addresses previously underrepresented ideas, which enriches the ongoing conversation in Philippine architecture.

You mentioned referring exclusively to two design titles: BluPrint and Kanto.PH. In your discussions with the two brands, what stood out about their views on the role of media in shaping architectural awareness in the Philippines?

The interviews often began by discussing reading habits—both for architects and the public. I specifically focused on BluPrint and Kanto.PH, as they played a crucial role in selecting the interviewees. I also interviewed three architectural journalists, all of whom had connections to BluPrint. Judith Torres, the former editor-in-chief of BluPrint, and you, her former art director, both now with Kanto.PH, a publication that evolved from BluPrint. I also spoke with Rick Formalejo, the current managing editor of BluPrint.

Kanto takes a more experimental approach, focusing on fresh content whilst retaining depth and incisive reporting, while BluPrint continues its tradition of regular modes of publication, a challenge in today’s fast-paced digital world. I admire that both publications maintain a clear editorial focus and diligently work toward their goals. BluPrint still has ambitions in print, believing that magazines and books retain the reputation of steady, lasting content, even as the digital landscape shifts toward constant updates. The Philippine architectural press is actively seeking new ways to remain relevant.

I also asked the architects about the role of architectural media in shaping their views. They emphasized the importance of quality writing, honesty, and diverse perspectives in shaping architectural discourse.

Were there any recurring themes or unexpected insights during the interviews that reflect the direction of architecture in the Philippines?

The core group of architectural communicators I interviewed in the 2015-2016 cycle included many non-architect intellectuals, as they had experience organizing and articulating their thoughts. Over the past seven years, however, developments in architectural education and the reflective time offered by the pandemic have fostered a more “open and conscious” architectural discourse in the Philippines. This maturing discourse is attracting more and more architects, expanding the small core group into a larger, more engaged community. Despite the challenges posed by social media, both BluPrint and Kanto.PH have maintained and intensified the architectural dialogue in the Philippines.

Let’s talk challenges; what were some you faced in conducting these interviews, particularly when discussing sensitive or controversial topics within the architecture industry?

With experienced architectural communicators, the challenge wasn’t in drawing out their thoughts. I found it easy to establish trust and encourage them to share their personal views. The real challenge was helping them express their ideas in a way that felt authentic even after they reviewed the written transcripts. I had to guide them to remain true to themselves, avoiding the temptation to become overly formal or sterile.

My goal was for readers to feel the communicator’s personality shine through the text and to sense their voice even without hearing it. I wanted the depth of their reflections to impress readers, but more importantly, I wanted their personalities to leave a lasting impression.

Another challenge came in the proofreading process, which required careful attention to ensure each communicator felt comfortable with how their words were presented. In some cases, interviewees chose to retract certain thoughts, which I had to respect. However, I aimed to minimize such instances. Ultimately, I believe the personal touch and authenticity of these interviews are the book’s greatest strengths.

Can you share an interview that surprised or deeply resonated with you during the making of the book?

One surprising revelation was that for some architectural communicators, the pandemic was a period of growth and introspection. It helped crystallize changes they had already sensed between 2016 and 2022, during a significant revival in Philippine architecture. Architect Jorge Yulo expressed this sentiment best, noting that the pandemic gave him the time to reflect not just on his own work but on the broader profession and its aspirations beyond merely building and earning.

Architect Anthony Nazareno also touched on a new appreciation for nature, which became an existential concern during the pandemic. What was once considered an architect’s dream became a practical necessity for clients seeking to create homes that could function as both workspaces and places of leisure.

While I wasn’t surprised that Architect Amon Cali, who began his practice during the pandemic through social media, found success in that environment, I was intrigued by Architect Keshia Lim’s experience. Despite starting her practice more traditionally, she also found new inspiration during this time. She realized that the advanced robotic architecture she studied in London would come to the Philippines much sooner than expected, driven by the country’s ingenuity and resourcefulness.

This has been a good exchange, Br. Béla, but let’s end with this: How do you hope your new book will influence conversations around architecture and public engagement with the industry?

Technical details about architectural works are typically found in architectural journals and books. However, it’s essential to explore the deeper roots of successful design. In my course on the Theory of Architecture, students often asked why I never presented Philippine architectural theorists, focusing instead on foreigners. Their question was valid, and my response was straightforward: we lack significant local theorists who have written and defended a substantial body of work. Most existing literature tends to be self-presentation or justification of an architect’s portfolio.

Reflecting on my experiences with Lantawan, the official architecture and art magazine of the University of San Carlos, I encountered talented Philippine architects who shared their struggles and doubts. They expressed deeper ideas about architecture that stemmed from their academic studies. This led me to realize that there is indeed a Philippine architectural theory, albeit subliminal and underexplored. Through the interviews featured in my book, researchers can systematize these ideas and establish a common theoretical framework for Philippine architecture. This approach offers a more objective and efficient evolution of the ongoing subjective debate on what constitutes “Filipino architecture.” •

Open and Conscious is published by Advaux and can be purchased for PHP950 on Shopee