Interview Patrick Kasingsing

Editing Gabrielle de la Cruz

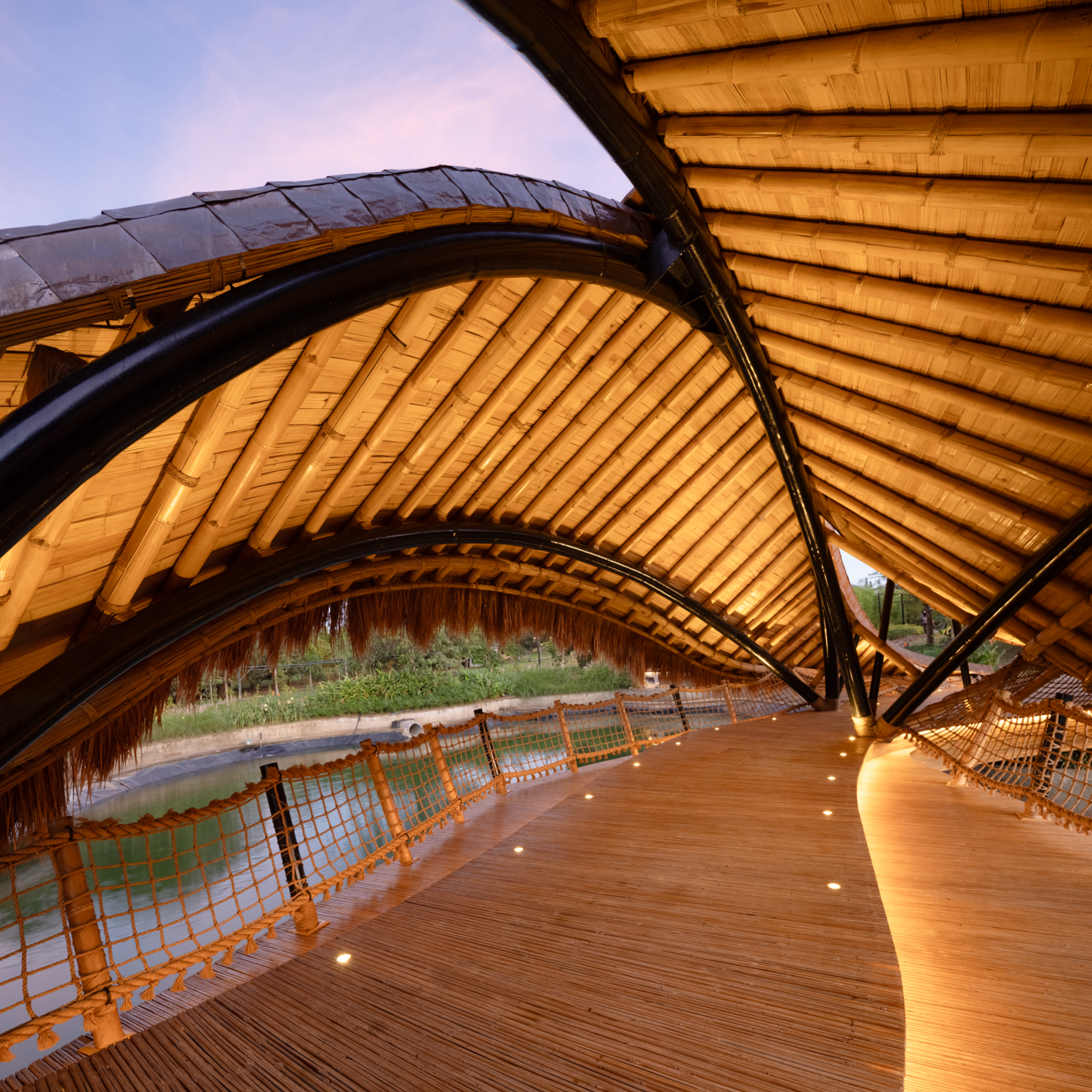

Images Studio Synthesis (Kaway’an EcoPark)

The Hardys see no limits in bamboo’s spatial potential, and one need look no further for proof than Kaway’an EcoPark in General Trias, Cavite, a three-hectare development hosting Luzon’s largest bamboo pavilion, a bamboo bridge, and nature-themed attractions and activities. The project is in collaboration with Bali-based architecture and design firm IBUKU, led by Orin’s sister Elora Hardy, Filipino architectural firm Sangay Architects, and British structural engineering company Atelier One.

“Our focus is on making buildings that blow people away,” shares Orin Hardy, founder and director at Bali-based construction firm Bamboo Pure. “We want to make the bamboo stadium or the bamboo cathedral, not the bamboo suburb. Mosques, churches, temples, stadiums, yoga shalas, fantasy homes—that’s our space. And what drives us is showing that something as humble as bamboo, if designed with intention, can be elevated to superstar status.”

Following a tour of the park, Kanto sat down with Elora (and an e-meet with Orin) to discuss the intricacies of dealing with bamboo and how that applies to Kaway’an EcoPark, their thoughts on the Philippine bamboo construction and design industry, and their high hopes for bamboo as a building material. We have edited the two interviews together for readability and brevity.

From the ground up

Hello, Elora and Orin! Thank you for indulging us with an interview. This first question goes to Elora.

You’ve spent more than a decade pushing the limits of bamboo—from its form, tension, and presence in the design world. And I’d like to say that the structures in Kaway’an, which we had a tour of, reflected that. But the site’s a bit different. It’s a vacant parcel, sort of suburban, edged by subdivisions—not exactly the most idyllic or romantic location. What kind of story did you and the developer intend for this space to tell?

Elora Hardy, founder of IBUKU: We’ve had the chance to build in many idyllic, natural settings in Bali. In the case of Kaway’an, it felt even more important to bring nature back into urban, suburban situations, so that people in cities can have a reprieve—a way to reconnect with nature. Recreating landscapes in that context becomes more valuable.

And we were really impressed by the position that Ma’am Rosie (Tsai, founder of Kaway’an Eco Park) took—to create a permaculture farm, and along with housing, build a space that brings the community together in nature.

We wanted to create a space that’s just a gentle shelter. And if you trace it back—before colonial times—we had more gatherings like this. So, we’re trying to recall that, to bring it back into modern consciousness.

Orin, you’ve worked with bamboo across countries and contexts, but did the Kaway’an EcoPark project present any technical, cultural, or climatic challenges that differed from your previous work?

Orin: I’ll start with the most basic answer: The Philippines is the windiest place on the planet, and bamboo is the lightest material on the planet. This implies the reality that bamboo can easily fly away, especially considering its need to be protected from sun and rain, which usually means sweeping overhangs and whimsical designs with columns leaning out.

The main challenge for this project was figuring out how to design a bamboo building in a place with wind load factors two or three times higher than what we typically design for in Bali.

On top of that, it’s in a different country, so the logistics were much more complex than a project in Indonesia—from workers to materials. Bamboo is available in the Philippines, but it was surprisingly hard to source what we needed: the right lengths, quality, size, and price. So, we ended up importing all the bamboo from Indonesia. The same goes for copper; we had to import prefabricated copper pieces from Indonesia as well.

That was interesting because we thought this would be our first project using regionally sourced bamboo, but economically, it didn’t make sense.

Is there a significant difference between the bamboo industry here in the Philippines and in Bali? Is Philippine bamboo a little more weathered from our climate?

Orin: Honestly, the bamboo species in the Philippines are great. Nothing wrong with them. You’ve got big ones, and you have Asper, which is the main species we use for structure. I would say you’ve got just as many amazing bamboo species as Indonesia.

The issue is the supply chain. We just couldn’t get poles at the lengths, diameters, and quality we needed—treated properly and within the project timeline. It’s also all about treatment facilities. But there are great organizations in the Philippines working to change that, which is exciting.

As for Kaway’an EcoPark, it wouldn’t have been possible without dedicated coordination between the design team, construction team, engineering team, and the client.

Now that you mentioned the client, can you share with us what drew you to say yes to CBDI’s vision?

Orin: The truth about clients is that we can’t afford to be too picky. If a client has the willingness and enthusiasm to work with bamboo and the funds to do something interesting, then we’re interested. Bamboo itself isn’t expensive. The heavy costs come during research, development, logistics, labor, design, and engineering.

So, it helps a lot when the client really wants to do something exceptional, beyond just thinking of dollars and cents. We look for clients who are in it for the ethics and the glory of it—not just the economics.

Above all, bamboo is still very much an experimental material. Even though we’ve been doing this for 15 years, the research and development and knowledge base around bamboo is still small compared to conventional materials. So, anytime a client is willing to do something exciting, well-designed, well-engineered, well-crafted—that’s a client we want.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but from talking with people working with bamboo, I’ve picked up on what feels like a split—or two schools of thought—in how bamboo is approached as a building material. Some see it as a practical, low-cost material for rapid construction—like our friends from Base Bahay. Others, like yourselves, push its expressive, sculptural potential.

Do you think those two paths are at odds? Or can they converge? And where do you see Kaway’an EcoPark on that spectrum?

Elora: It’s essential to have both. Our practice has been pulled forward by requests to create something extraordinary—to demonstrate what’s possible, to bring attention to the material and to nature. That kind of work has only been possible because of clients with budgets that support innovation.

And from early on, we’d get asked: Okay, great—but what about everyone else? The truth is, almost no one has wanted to invest long-term in making bamboo construction low-cost and scalable. Base Bahay is one of the few doing that—and we really admire it. That work is essential, more important in many ways than what we’re doing.

But our projects have led us in a different direction: toward drawing attention to the material. And without that, there’d be far less public interest in bamboo overall. Even in Bali, in my experience, people who simply needed a house didn’t want bamboo. If you asked a Balinese person ten years ago, “Would you want a bamboo house?”—they’d say absolutely not. Their grandmother had one because they couldn’t afford a wooden house, and it didn’t last—it wasn’t treated properly.

But now we have proper treatment methods and proper design innovations. Bamboo can be a long-lasting building material. It is reliable.

Orin: For Kaway’an EcoPark, I think it’s worth noting that what makes it unique is that it serves a different demographic from our usual work. Normally, we’re in the high-end bracket—hospitality, private homes, people in the upper strata.

CBDI focuses on aspirational homeowners entering the middle class in the Philippines. The fact that this project is going to serve your average or middle-class Filipino is really special. It’s amazing for bamboo to reach that group, because in many places, bamboo is either seen as a poor man’s timber or as a high-end designer material.

For it to land in the middle class shows it’s moving toward the mainstream.

Because the stigma needs to be let go.

Elora: Exactly. In Bali, the work we’ve done has generated a lot of interest in the hospitality world. Many hotels or Airbnbs now have at least one bamboo structure. And that shift is making people reconsider bamboo. So even local people are starting to say, “Maybe I do want a bamboo house.”

Because no matter what you can afford, your home is part of your identity. You want to trust the materials—it’s emotional as much as it is practical. That’s what’s important about what’s being done here. I would say Kaway’an EcoPark definitely sits on the expressive end of the spectrum.

It’s a significant investment meant to make a statement—and in the Philippines, this kind of structure is still rare.

Detail shots of the Bamboo Pavilion at Kaway’an EcoPark

Proper connections

“Sangay Architects approached us as collaborators,” Elora recalls when asked about the first phases of the project. “What we liked about working with them was that they understood the value of building a relationship—not just for this project, but for the future of bamboo design in the Philippines. I could tell they were thinking long-term about what they could learn and build from this. That was powerful.”

Throughout the interview, Elora and Orin also highlighted the experience of working with Atelier One, who initiated perhaps the most surprising addition to a project that bannered bamboo: a structural steel arch, added to keep the bamboo structure in place. It was a necessity for a country where extreme weather and ferocious winds have long been architectural constraints.

Can you elaborate on what it was like working with Sangay Architects, who also champion bamboo as a primary material?

Elora: It was great. I think having a Philippines-based design firm like Sangay—which not only found the client but also understood the value of bringing bamboo to the Philippines—was key. I appreciate how they saw what we were doing in Indonesia and took the extra effort to collaborate with us. A lot of people try to copy what we do—look at some photos on Instagram or Pinterest, do a tour, and think they can build something comparable. It’s just not true. The result usually doesn’t match the expectation.

Often, when there are many collaborators, it takes more time to coordinate. Some clients or firms lose patience and want to cut corners or rush things. But Sangay gave time and space for each party to do their work properly.

Even when it came down to the construction phase, which is usually the one that gets squeezed in time and budget, they made sure we could execute properly. We always joke that it takes 18 months to design and six months to build, which is unrealistic, but that’s the pressure.

Here, we still had those pressures—time is money—but the design and planning were solid. We had only a few issues, and those were handled well because everyone understood the process. And again, I don’t think any of it would’ve been possible without Sangay’s leadership. We couldn’t have done it with just any architect, anywhere in the world. It needed their specific experience.

That’s good to hear! Because in the Philippines, foreign architects are often required to partner with local ones, but sometimes the local partner is just there on paper, not contributing much, and simply meeting the requirements. Basically, the AOR just implements what the name-brand architect wants and value-engineers it. It’s refreshing to know that your process felt like less of a compromise and more about everyone getting personally invested in making it work.

Orin: As for me, I wasn’t involved in the initial design process, as Bamboo Pure doesn’t really come in until later. IBUKU and Sangay already had a relationship with the client. And we have a special relationship with IBUKU, as we usually execute their more complex bamboo projects around the world.

I don’t know the early-stage details, but when I entered the picture as Bamboo Pure, it was clear to me that Sangay had played a leadership role in coordinating the project and bringing the client to us. They were definitely not just paper architects. It was clear they’d identified us as the right fit for the client. I’d say they were really leading the process, and in some ways, outsourcing the expertise they needed to us to make it happen.

Fantastic! I was telling Kwi (Wang, general manager of Kaway’an EcoPark) that for this project, you’ve got all the superstars: IBUKU, Atelier One, Sangay, and Bamboo Pure. I believe this meant being able to really stress-test how bamboo could handle our crazy weather, adding that there were three typhoons in succession in the two weeks before opening.

Orin: Yes! Atelier One is one of the best lightweight engineering firms in the world, as far as I know. They’ve been working with us for about ten years, learning how to build innovative designs with bamboo. They also brought in mixed materials, like steel. Admittedly, I was concerned at first about how a steel backbone would look, but it ended up adding to the aesthetics and balancing with the bamboo beautifully. The designers found ways to incorporate steel that didn’t feel hidden or disguised—it was authentically part of the structure.

It’s important to recognize that bamboo is amazing, but it has limitations. We are called Bamboo Pure, but we’re not purists. We like low-embodied-energy materials, and while bamboo is usually the protagonist, it’s not always the sole character. We often incorporate wood, steel, concrete, lime— whatever makes sense. But in most of our projects, bamboo takes the lead.

In the case of Kaway’an EcoPark, bamboo was still the structural element. The steel spine wasn’t holding the building up—it was keeping it on the ground.

A closer look at the steel spine of the bridge

I see. The bamboo columns are doing the work of holding the building up, but because the building is so light, the risk is that it could lift. And the weak point of a bamboo structure isn’t the bamboo itself, but the connections, right? So, I see what you meant that a lot of research went into figuring out how to connect the bamboo to the steel in a way that’s strong and still visually pleasing.

Elora: And we had to take on the challenge of creating a structure that could handle the serious, extreme weather, aiming to show that bamboo could play a major role in that aspect and not to prove it could do everything—that’s never the point.

It shouldn’t be on any material’s shoulders to solve everything. That’s why it’s about working together, much like how a community collaborates. You don’t have to go all the way with one material. But you should bring it into the palette. Learn it. Integrate it.

We ended up with a great balance between steel and bamboo to meet the site’s very tough structural requirements. But still keep the space lovely and usable every day.

You can make a building really strong—but would it still feel light, breathable?

The engineering is also interesting, as it demonstrates that people who usually work in steel may consider using bamboo. Steel helped us bring in curves. With bamboo alone, it would have been harder to make a curving structure. From an engineering standpoint, it’s also easier to calculate loads and forces in a symmetrical, linear system, so steel helped us close that loop.

I’d say steel is the zipper; it allows movement but holds the shape.

Orin: Don’t get us wrong, it’s possible to build a full-scale bamboo structure in the Philippines. But then it becomes a design question.

In this case, the roof materials were synthetic thatch and copper shingles—basically bamboo shingles with copper flashing. All of that is still lightweight.

I find that to go full bamboo in the Philippines, you’d need a much heavier roof. People are doing fully bamboo structures in the Philippines, but location matters—especially how typhoons move through that region.

Everything’s possible. But you have to design for your context and avoid being dogmatic. Bamboo was used where it made sense here—for the place and the purpose.

And that’s something we always ask ourselves: Are we using bamboo in a way that makes sense? Are we making sure we’re using it for its highest potential?

And in the final product, bamboo still looks like the protagonist. I was unsure at first how to feel about it—I wouldn’t call myself a bamboo purist, but whenever I get asked to visit bamboo-centric projects—especially the ones marketed as “all-bamboo”—I’m prepared to be disappointed. Usually, the bamboo is just cladding. It’s not structural. It’s used as a visual garnish, not as something integral to how the thing is built.

Orin: We have a term for that. It’s called bamboo washing.

I wasn’t sure what to make of that huge steel arch at first, but it really integrated well into the structure. It didn’t feel like a utilitarian, exposed structural element.

Orin: I think IBUKU really went out of their way to meet engineering standards without compromising the design.

Was Atelier One responsible for the inclusion of a steel spine to weigh the structure down?

Orin: Yes. They were trying to find a way to make that leaf-shaped, whimsical structure survivable. The designers obviously wanted it to feel floating, light, breezy, and bamboo. The engineers had to figure out how to withstand 200-kilometers-per-hour winds.

It’s a beautiful solution. I think one of the not-so-wonderful effects of coming up with something so iconic, like, for example, the bamboo campus you have in Bali, is that people want to get in on the fun, but not on the thinking behind it, or why it’s even there. You get surface-level copycats that do not take into account the practicability and longevity of their creation.

Orin Exactly. In the context of bamboo buildings, a lot of people see them and think they’re vanity projects. But there’s a lot of functionality behind the shapes. It’s not purely design-led. A lot of it is necessary.

And we have to remember that bamboo has weaknesses. The sign of a really good bamboo designer is someone who can take those limitations and use them to their advantage to create something aesthetically stunning.

Building with bamboo

As the conversation progressed, our lens widened with a deep dive into bamboo as a building material, realizing its current place in the construction industry. The truth, according to Elora and Orin, is that while recognition of bamboo’s spatial potential is important, what is truly pivotal is one’s openness to experimentation—and failure in order to truly reap what the material can bring. There is also a need to systematize the processing and use of bamboo and be cognizant of its supply chain.

“We still have a lot to deal with: supply chain, building codes, smarter engineering, and perception. All of it needs work,” Orin shares, to which Elora adds, “I believe it’s mainly about us and the way we value our resources. If we acted like part of the biosphere, we wouldn’t have the problems we do—with neighbors, with health, with the environment.”

Let’s get into some particulars. What barriers—technical, regulatory, or perceptual—prevent bamboo from becoming a ubiquitous building material?

Orin: The reality is that there are lots of barriers. Bamboo construction isn’t for the faint of heart—and it’s definitely not for the accountants. And right now, I think accountants are running the world.

The biggest barrier is that it requires a lot more thinking, creativity, and a higher appetite for risk and experimentation to become something ubiquitous. Everyone’s trying to turn bamboo into a square, thinking that once it’s square, it’ll be usable everywhere. But turning it into a square is very complicated. The Chinese have managed it, but they had to go to great lengths—and their political system made it possible to scale it to the larger market.

What drives us, despite all that, is the fact that no other building material shoots out of the ground this rainy season and is ready for construction in four years—and can then last in a building for 40 years, maybe even a century. The lifecycle, from a sustainability point of view, is incredible. And in terms of strength, it’s extremely strong.

A bamboo plank that weighs a fraction of a concrete slab is much stronger. We recently did a course comparing a two-centimeter concrete slab with a two-centimeter bamboo plank. Besides being lighter, we could put three times more people on the bamboo plank.

So yeah, it’s legitimately lighter and stronger. But then there’s the supply chain, durability, fire, and general industry acceptance. Unlike steel and concrete, bamboo behaves differently under different forces. It’s anisotropic—it doesn’t behave the same in every direction. That leads to a lot of challenges.

Do you see Bamboo Pure’s work expanding beyond Southeast Asia? If so, what regions or contexts do you think are most ready?

Orin: I see Bamboo Pure as a pioneer and promoter of bamboo to the world—not necessarily a company that needs to become ubiquitous or standardized. We’d have to be a completely different kind of operation to do that. I hope what we do inspires others to go that route.

It’s about more than bamboo. It’s about showing how to design with nature, how to design using diverse materials, and how to design for people—not just for the accountant’s spreadsheet. Of course, economics matter, but it’s about adding beauty and sustainability to the conversation and recognizing that there’s value beyond what shows up on a spreadsheet. Value that’s actually priceless—for communities, for humanity, and for quality of life.

A concrete box might be cheaper, but what’s the cost to your health and to the future?

In the Philippines, ideas like archipelagic thinking or reclaiming pre-colonial stories and mindsets and pre-colonial lifeways are starting to reframe nature not as adversary, but as collaborator. We’re still working on it, but there’s progress. Bali, meanwhile, has a deep heritage of land symbiosis. As people who’ve worked closely with bamboo—and as non-Asians—what insights have you gained about how materials like bamboo help communities reconnect with ancestral knowledge or ecological resilience?

Finally, how do you see flexibility and impermanence, as seen in bamboo, as strengths rather than limitations in architecture?

Orin: You’re right, this is an important question. And our answers will be long. Colonial thinking brought everything from pants to concrete to squares. A lot of valuable knowledge has been lost. We can’t change the past, but we can reclaim what place-based architecture looks like.

Ironically, some of the people driving the renewal of traditional craftsmanship through design are foreigners—the children of the colonists, so to speak. We really value the relationship between tradition and innovation.

Sometimes it takes that outsider perspective to really validate local wisdom. I don’t think the Balinese would’ve figured out the full potential of bamboo so quickly without someone from a European background seeing it not as poor man’s timber but as something exotic and beautiful. I would say there is this identity tectonics happening—collaboration, shared understanding, letting go of the past, and looking forward together.

In the Philippines, I’ve observed it’s not about rejecting colonial history or global economic realities, but about not undervaluing local materials and craftsmanship. There’s a whole bamboo culture there. If designers recognize that—if they intentionally include people with those skills, whether batch work or structural work—there’s so much potential.

If that process also benefits those communities, it’s powerful. In Bali, most of our builders come from just a few villages. Our work is elevating those communities and taking their craft from cheap handicrafts to high design. And they’re seeing real, tangible benefits from that.

Circling back to what I said about outsider eyes coming in to validate things that local cultures may have forgotten are unique or valuable: If you don’t have a good reference, it just becomes ubiquitous or something you take for granted. Bamboo is interesting in that it grows in the places where it’s most needed.

The places where we need the most homes in the world are around the equator, and the best bamboo is also around the equator. The question is: how do we move from being outsiders? It’s debatable. I’m actually not a non-Asian because I grew up in Asia—I grew up in Bali and speak Balinese and Indonesian fluently. So even though I’m technically not Indonesian, I do feel an affinity where those lines are starting to blur. As a third culture person, I understand the power of seeing something both from the inside and outside.

Elora: The way I see it is that bamboo isn’t something we use—it’s something we learn from. I think nature speaks through bamboo. Even the language we use—at least English—frames nature as something separate from us. We talk about things, not beings. But the older ways of thinking—across cultures—understood that everything is interconnected.

We’re connected to everything around us. That’s identity. That’s beingness. I see bamboo as a teacher and a guide. People say we’re advocates for bamboo, but actually, bamboo is helping us reconnect—with each other and with what we’ve separated from: the rest of the biosphere.

So, you’re using bamboo to help spark that reconnection—embracing the kind of oneness our ancestors once had?

Elora: The ancestors weren’t just aware of it—they lived in ecosystems they were part of. Not dominating them. They embraced the tension.

Western, colonial culture didn’t just dominate people—it dominated whole functioning systems that the people had seen themselves as part of.

Bamboo teaches us to be flexible. To bend without breaking. That’s where its strength comes from—its ability to shift. It moves with the storm. It lets the wind pass through. It teaches us that you’re stronger in a clump. Generations succeed each other within that clump. And what’s happening underground—that’s the actual source.

You look at a bamboo pole and say, “That’s the plant,” but it’s just a branch. If it were a tree, that would be one branch. The root system underground—that’s the real bamboo.

And the more I learn about bamboo—its cellular structure, its lightness, its flexibility—the more I connect it with how I want to relate to people.

In our studio, we talk about how we want to be, how we want to respond to stress. We talk about flexibility and uniqueness. Because we have to recognize that every pole is different. We are all different.

There is tension in difference, but also strength and beauty if one is willing to put in the work to cooperate and build unity. •

2 Responses