Words Miguel Llona

Images Greg Mayo and Patrick Kasingsing

Building one’s house could be a challenge, perhaps even more so for seasoned architects. There’s often pressure to design a home that would reflect your values and aspirations, leading to increased worry over each detail so you can bring that dream house to life (and not lose face among one’s peers!). Architect Alfie Agunoy had none of that baggage when it came time for him to build his family’s nest; tempered with a tight budget, he treated the construction of his house as an experiment to test out design principles, DIY-ing select nooks and crannies out of curiosity (and in the name of savings) to trying out the most unorthodox palette of materials. The resulting home is an alien-looking volume in a sea of Mediterranean and Swiss chalet pastiches; On the day of our house call, it had one visitor, a delivery rider, audibly question whether the structure in front of him was a house.

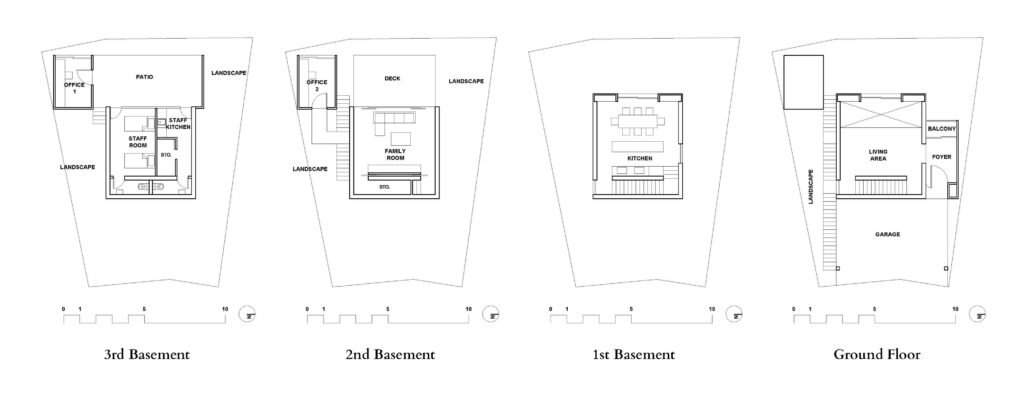

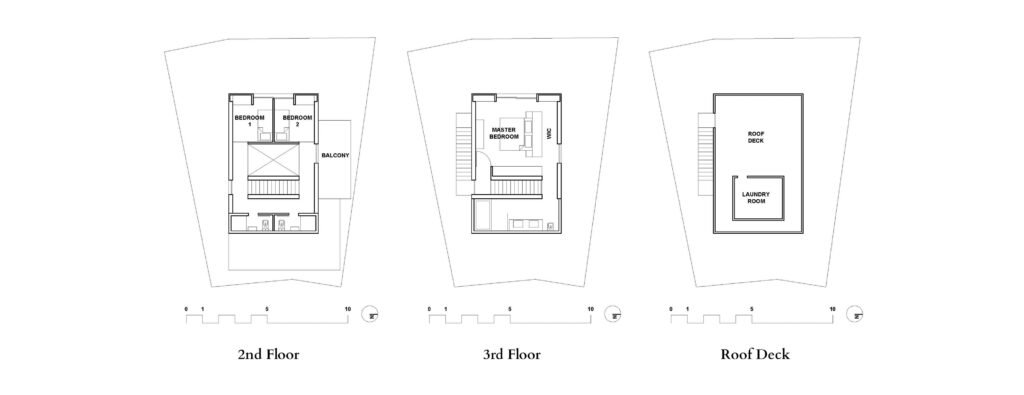

Christened the Robot House because of what its form reminds Agunoy’s family of, the entire structure is built like a single block of concrete straddling a steeply sloped 160-square meter lot. The eastern façade is aloof, its black surface interrupted by a sliver of a window on its upper left corner. It is only on the western façade, seen from the street below, where one can see the true number of levels the Robot House possesses, of which it has seven. The precipitous slope of the lot enabled this multi-level configuration, while Agunoy’s intuitive design process essentially dictated the building’s form.

“I don’t want the material to pretend to be something else,” says Agunoy. “If you use a simple material and detail it wisely and carefully, you will really elevate its value.”

Agunoy shares that the design evolved around the low budget he had set, but this pragmatism tied in with his philosophy of respecting the site and prioritizing material honesty. Tadao Ando’s 4×4 House in Kobe, Japan is an obvious inspiration, though he says he only realized it midway through construction. “I kept going back [to the 4×4 House] mostly to validate all the things I did, like the circulation, the focus on common spaces, and the sizes of rooms,” he says. Like the 4×4 House, the entire composition of the Robot House is dependent on the plot of land it’s on, although the structure doesn’t eat up the entirety of the sloping lot. Another similarity with the Tadao masterpiece is the way the materials are treated, in that they don’t hide behind coats of paint or other finishes. “I don’t want the material to pretend to be something else,” says Agunoy. “If you use a simple material and detail it wisely and carefully, you will really elevate its value.”

The open garage lays bare Agunoy’s design philosophy for the house. Through the grills of the garage floor, one can see how the main volume is set back from the slope so that the natural contour won’t be disturbed, minimizing the footprint of the structure. The garage functions as a bridge from the street to the house and creates space for a garden below which can be seen through the floor grills. The concrete surface of the garage wall, perforated with the anchors from the formworks, provides a preview of how the materials are exposed in their natural, unpolished form throughout the house.

The Robot House’s simple form belies the complex programming that Agunoy was able to carve out for its interior spaces. From the narrow foyer, one is led to the double-height living area that essentially functions as the central axis from which the other spaces unfold. The living area serves as a pseudo-mezzanine that looks down on the dining area below, with only drawn-out netting acting as a partition to prevent people from falling. The same netting can be seen in narrow pathways flanking this area above, which connect the children’s rooms on the west-facing side and the bathrooms on the east that were divided by the void of the double-height living room. Three more floors were created below street level, among them the aforementioned dining area and the family room another level below. The lowest level is dedicated to the maids’ quarters, shaded by the outdoor deck stemming from the family room. A separate volume was built on the north side, containing Agunoy’s home office.

The nets are certainly an unconventional building material, but they were chosen to provide transparency between areas and to facilitate air circulation around the house, which could potentially become a heat sink because of its generous use of concrete. To prevent the buildup of stagnant air, several openings in and around the house are created for air to pass through. The ceiling fan over the dining area, which is level with the living area, helps push any stagnant air up towards the staircase on the eastern side and out through the windows on the north- and south-facing sides. The absence of risers for the stair steps ensures that heat doesn’t get trapped, a common occurrence in the staircases of poorly-ventilated houses.

Similar to most of Ando’s projects, light plays an important role in the Robot House. Agunoy configured the layout in a manner that draws anyone’s gaze towards the panoramic view to the west, made possible by the floor-to-ceiling windows on the house’s western wall that cuts through every level. The bare concrete walls glow with different shades of sunlight flowing through these windows, and this interplay of light and material breathes new life into the house throughout the day and effectively acts as the paint that colors the walls.

While Agunoy confesses that the decision to leave the walls unpainted was borne out of budget concerns, his love for concrete can be felt in every corner. Character shines through in every mark of structural epoxy left on the walls and the weathered grain of the reclaimed wood used for the upper floors. The use of reclaimed materials is a recurring theme throughout the house. Agunoy scoured the nearby warehouses of Taytay to look for reclaimed wood planks for his doors, stairs, and floors and even found discarded travertine tiles to clad the en-suite bathroom of his master bedroom. These materials provide a tagpi-tagpi or patchwork quality to the project, something that builders like Agunoy can appreciate.

The bare and honest form of the Robot House is reflective of its unfinished state and follows Agunoy’s idea of what a house is. Several design elements were added or changed as the design process went on, such as the cantilevered staircase on the south wall leading towards the roof deck that was initially supposed to be where the master bathroom is. “[Designing a house] is a continuous process,” he says. “I treat this house as a blank canvas because I’m sure my tastes will change over time. The bare concrete keeps it timeless.” From the outside, the Robot House appears to be deep in thought, still computing what its final form ought to be while its inhabitants enjoy its spatial programming. •

Miguel Llona is a writer who has written for numerous print and online publications. He was a former editor at BluPrint magazine, and currently serves as marketing consultant for an interior design firm and a structural engineering company.

2 Responses

amazing concept design. you definitely make us proud alfie!

thanks for the sharing.