Interview Gabrielle de la Cruz

Images TROP

Kanto: Nice to meet you, Mr. Pok! Let’s start with your studio’s design philosophy and approach. Can you walk us through a project from your portfolio that best represents this?

Pok Kobkongsanti, Founder/Design Director of TROP: Hello, Kanto! Thank you for inviting us to your World Landscape Architecture Month special. There is this philosophy by the famous martial artist Bruce Lee, which says “Empty your mind, be formless, shapeless, like water. You put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle, it becomes the bottle. You put it into a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Now water can flow or it can crash. Be water, my friend.”

I patterned our firm’s approach after this. We do not allow ourselves to be trapped in a certain mindset. Like water, we let our designs take the shape of its site, context, surrounding architecture, and even the constraints. The name of our studio is also reflective of this, as TROP means “the earth” (terrains) and “open spaces.”

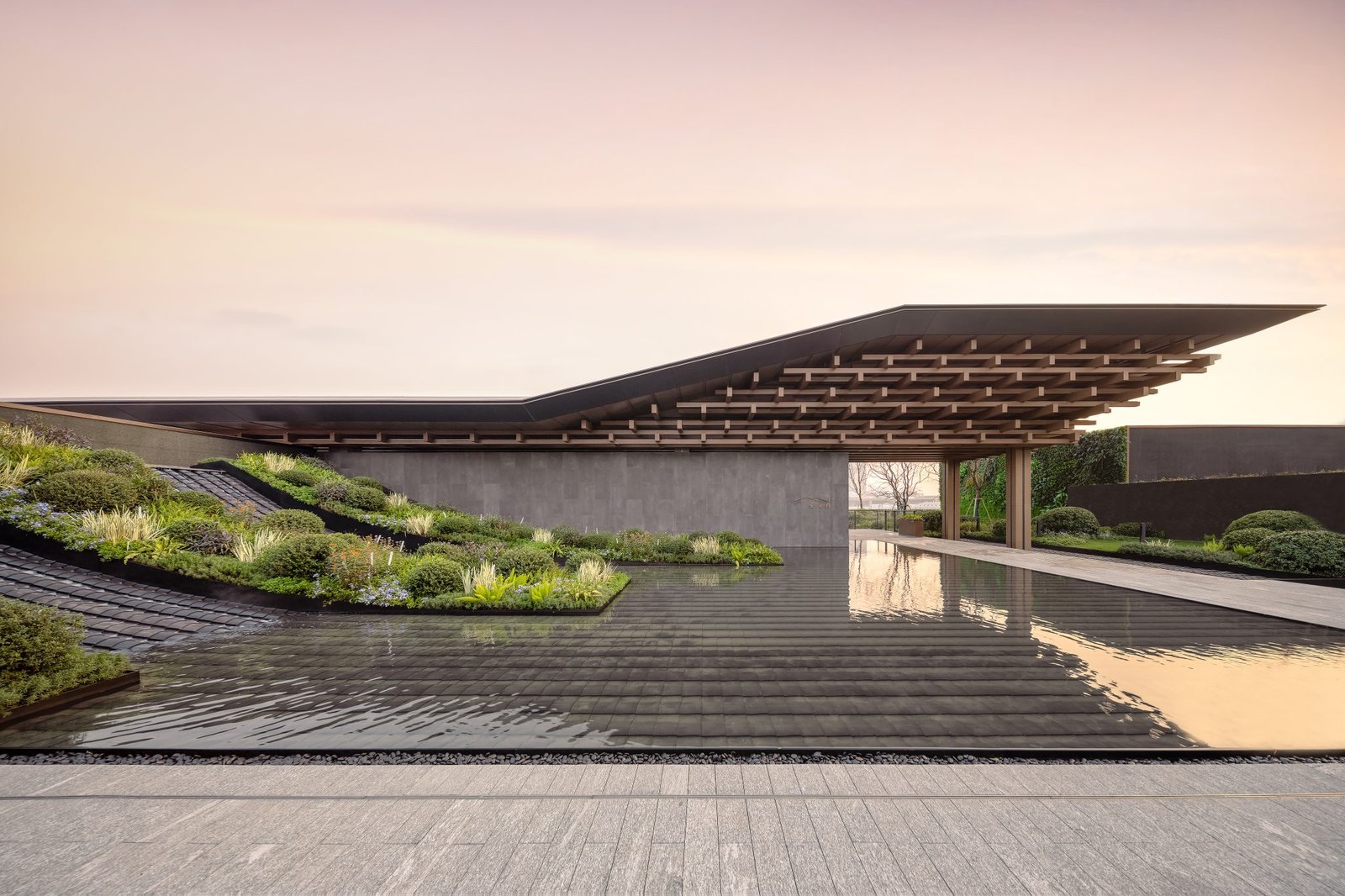

All our projects are reflective of our design philosophy. Perhaps one example I can share with you is An Villa, a residential landscape design project we did in Shaoxing, China. We studied the history of the city and strived to preserve the memory of the place. We discovered that back then, the people living in Shaoxing were not very rich and their houses looked alike, all using clay tile for their roofs. We also found that they experience a lot of rain and that many of them remember the scene of raindrops hitting the roof eaves. So, we installed sloping clay roof tiles to mimic the look and feel of their place back in the day. We also added a water feature at the arrival court for good outdoor scenery, and we designed their residential lobby as a sunken garden where they can experience the roof installations better. It’s important to us that the designs we put out not only respect the context but also represent the culture and the memory of the community.

I admire your dedication to what you do! What’s one aspect of your design process that you find most enjoyable or fulfilling? How does this reflect your personal design inclinations or ethos?

I like the sketching and the concept design phase. I design most of our projects and I start every project the same way—getting to know the site, determining the problem, and finding a solution. My favorite moment is when I can simply spend time with the site, the drawings, and the model, and work on the landscape design from there.

After that, it’s usually about bringing all the ideas to life and translating them into something physical. There will be more applications and more people will be involved, so I just like having that moment where I feel like I am personally connecting with the project.

In what ways do you believe the current professional understanding of landscape architecture in the ASEAN region differs from global trends? How do you navigate this intersection between local culture and international design standards in your work?

I think landscape architects all around the world are working on the same thing. Our goal is to simply make the world a better place and design a better environment. I don’t see a huge difference between ASEAN and the rest of the world.

In terms of technology, I believe our region is also facing the same thing with everyone. The world is not small anymore. Every country has access to technology, and it’s up to us designers to see it as a tool or a threat. The rise of BIM and the like has proven to make our work more efficient and more accurate. AI, on the other hand, can be a little threatening as we really cannot predict what else it can do in the future. There are speculations that AI may replace actual human beings in certain roles soon, which is something that I do not wish to happen. There is value in adding a human touch to everything.

In the context of sustainability, I believe that landscape architects are also on the same page. I don’t know a single landscape architect whose dream is to destroy the world. We all want to design something that lasts and something that people enjoy. Still, I believe that every place has its own style. Although we share the same tropical conditions, the Philippine landscape is still different from Bangkok’s. The way we see things is never going to be the same. And I think that’s a good thing because we get to tailor our designs concerning our surroundings and our understanding of our culture and our people.

Besides, it would also be boring if everyone did the same thing, right? I love looking at new places and spaces, especially those that we do not have here in Bangkok. I like how we’re progressing now and designing gardens that are not only for the rich, and how more and more people are claiming their right to have green space.

I like how you pointed out that green space should not only be given to people who can afford it. How do you think landscape architects can help ensure that communities, especially those in urban areas with limited access to nature, have fair access to green spaces and parks?

This is such a good question, and I understand your intention. But the truth is that landscape architects cannot do this alone. We are specialists in design, and we can only do that if we are given a site or an area to plan. If a community does not have the space, then it will require more than just landscape architects. Everyone in society, starting from our leaders to the locals, will have to take part.

We put out our work, and our ideas, and share our input in the hopes of making society realize how green spaces can improve overall quality of life. But the real difference is when we get to convince people, especially those in power, to design something for such communities.

In connection to equitable access, can you share a project from your portfolio that embodies your design philosophy and commitment to diversity and inclusion in landscape architecture?

Any public park should commit to diversity and inclusion because the space will be open to people from all walks of life. Our first project after we set up our practice in Shanghai was to promote pedestrian accessibility for visitors and the community of the Grand Milestone Art Centre, which was envisioned to be a sales gallery and clubhouse in the development. Among the challenges for us was to make the space as inviting as we could, as its location was 10 meters across the highway.

We proposed a boardwalk that reconnects the existing footbridge and pavement with the new development. We called it the Ribbon Dance Park, as the curves of the boardwalk are reminiscent of the Chinese Ribbon Dance. The name and design of the project also helped connect more locals and even the government wants more green space because it is something that resonates with them. Now, people get to enjoy the boardwalk and connect with the greenery.

What work by a fellow landscape architect, local or international, do you find beautiful? What for you are the hallmarks of a beautifully designed landscape?

I like many projects all over the world! The High Line in New York, a collaboration between landscape architecture practice Field Operations and garden designer Piet Oudolf, is at the top of my mind right now. I like how their concept respects the origin of the site, which is an abandoned train line. Plenty of trees grew without anyone planting them in that line, so the designers captured that essence and created a new park for locals to enjoy.

For me, the most beautiful landscape design is one that belongs to its site. It is a design that has a sense of place, a design that moves its community forward.

Can you discuss a project where you had to challenge traditional norms or expectations in landscape architecture? How did you navigate potential resistance or pushback, and what were the outcomes of incorporating innovative approaches into your design?

I’m not sure about the rest of the world, but here in Thailand, there is this practice that people will cut down healthy trees in an existing landscape, and then plant new ones. And honestly, I don’t get it. The best tree for a landscape is an existing tree. In our studio, we try to work around old and existing trees. If possible, we try not to cut them down.

There is also a trend in Thailand where people like to purchase expensive Olive trees and place these in their gardens or green spaces. Some people like trees like this because they’re hard to acquire, sometimes hard to find. But nature doesn’t care about all that. Only humans do. What matters to nature is that we take care of it.

In one of our residential projects, Quattro by Sansiri, we opted to work around existing mature raintrees. If you grew up in an old house in Asia, chances are you have three tree generations: grandparents, parents, and children. For this site, the rain trees were the grandparents; they were about 40 to 50 years old. We designed the condominium’s garden in such a way that you can look at and acknowledge the trees from every angle of the site—the same way that we Asians take a bow, bend, nod, and show respect to our elders when we pass by them.

This project means a lot to us as we were able to convince the owners to locate the residential towers away from the rain trees and preserve the existing greenery. We also fought to retain them for the sake of the squirrels and birds who are already inhabiting the space and wanted it to benefit the new residents of the project as well.

On another note, we also had a project where we had to deal with budget constraints. One of our first residential projects here in Thailand, Pyne by Sansiri, is a garden for a high-end condominium. The site is convenient as it sits next to the Bangkok Sky Train station (BTS) and is a 5-minute walk from the most popular Bangkok shopping malls. The problem is that the space feels crowded, as it is surrounded by giant concrete boxes and even neighborhood nightclubs. The challenge for us was to design a garden that would take people out of the city and create a boundary between the condominium and the busy streets. Our solution was to integrate a 3-meter wall with planters on top to make at least half of the train station disappear in the backdrop. We also planted 10-meter-tall trees to reduce the impact of the nearby station.

Unfortunately, the budget was short and we had to cut down the 3-meter wall to 1-meter. In cases like this, we just tell ourselves that we cannot win every argument. As designers, we give the best advice we can, but it’s still up to the clients if they will follow us. We also hope that people will see the difference, whether they take our advice or go in a different direction.

Now, what are some overlooked or underestimated aspects of landscape architecture that have significant implications for the future of urban planning and development in the ASEAN region?

I wouldn’t say it’s overlooked or underestimated, but many landscape architects need to study more about plant species. I say this because we like to design space, but we don’t really have the technical knowledge about plants. It would be nice if we could discover more implications, like the benefits of each plant to the ecosystem. Of course, we don’t just place plants without looking at whether they can grow and help the site, but it would be better if we could dive deeper and discover more about the plants we use.

One example I could cite is how we can look for more plants that can help eliminate harmful insects in our garden, especially since we experience a tropical climate. I know that there are already a bunch of plant species designated as insect repellants, but it would still be nice if we could discover more of them. I personally feel like I still lack knowledge about these things, so I want to educate myself more about it.

What hobby or interest outside landscape design unexpectedly influences or informs your work? How do you integrate these diverse influences into your design approach?

I turn to architecture, art, and even food for design inspiration. I find looking at different colors, textures, and patterns refreshing. I especially like looking at installation art, as this helps me create ideas for interventions in our landscape designs. Landscape paintings inspire me a lot as well, especially those that aren’t realistic. I find that they evoke emotion and spark the imagination.

As for hobbies, I collect toys! This doesn’t affect my work in any way because I don’t want it to connect to what I do. It’s important for me to have something of my own outside of my profession.

For our last question, as a landscape architect, what do you see as your role in addressing pressing environmental issues such as climate change and urbanization?

I’m not the type of landscape architect who likes to say that I want to save the world. I just want my work to help the locals. I want to see my projects affecting neighborhoods and creating better environments for people. I like to describe what I do as “creating micro-climates.” If my design means something to the people I created it for, and it makes them comfortable, then I feel successful already.

They always say that small things, when combined, result in bigger things. If we take your work and the work of all the other landscape architects out there, it’s safe to say that together, you guys are making the world a better place.

Thank you. We cannot design parks and say that they will save the world. But I do hope that as more and more people see the impact of what we do, then they will understand why making these plans and coming up with these designs are vital to the growth of our environment.

As for us, we will continue to be water, allowing the flow of our surroundings and everything that makes up a site to shape our designs. And hopefully, we will impact more neighborhoods and bring more joy and comfort to communities. That’s all that matters. •

One Response