Peter Mendelsund, as told to Karl Castro

Images Penguin Random House

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity

I lived in a house with my grandparents; they were survivors of the Holocaust. In the Warsaw ghetto where they lived, you were not only poor but you were discriminated against because of your ethnicity and religion. There were very few ways out, and the two sort of acceptable means were medicine and music.

My grandparents were very cultured people, and I think they wanted my father to be a musician. He was too strong-willed and didn’t want to practice, so they gave up. When he became older, my father was incredibly sad about that. He wished that he had developed those skills and was able to play. There are certain fields where you have to start young, and classical music is one of those. And so he made a decision when I was young that he would force me to learn.

I started when I was four. I have memories of being like six or seven, just really not wanting to practice, and my dad locking the door, being like, You’re not coming out until you can play that. It was imposed on me, I cried a lot, and it was not a fun experience, but I remember he said I would thank him. By the time I was around 12, I really loved it. My number one fantasy when I was a kid was to be Vladimir Horowitz, or Glenn Gould, to be some great pianist. I had constant daydreams about being on stage at Carnegie Hall or some big space where I was playing some romantic warhorse. (Now I come home and I can crack open a volume of something and play it, and I have nothing but gratitude towards my father.)

Music was always there. When I was a kid, that was my dream, really.

And then I went to college. In Columbia, they have a core curriculum of basic humanities, education, and you’re required to do literature, political science, and philosophy. You don’t have a lot of room or time for other things. At that point, I found that music was something I had to do in my spare time, which I did. But also around that time, I began feeling a little tired of being in English classrooms where people say things with no sort of logical armature.

The thing that was compelling to me about philosophy is that it just seemed very rigorous. The questions in philosophy always seemed to precede the questions in literature. In fact, they seem to precede every question, like why are we here? What is the good life? What is the nature of experience? Is there a soul and where is it located? All of these questions are literally fundamental. They’re the first questions and the most important, and I found myself very compelled by that.

But I hadn’t stopped doing music, and when I went to graduate school, it was for music. It was for piano performance, composition, and theory. By the time I was done with that, I think I was pretty burned out on all of it. Graduate school and conservatory are literally ten hours a day of practicing. My hands hurt, and I just wasn’t getting anywhere; it’s a really hard field. And we needed money.

At the end of the day, that was it. We needed money, and that’s how I became a designer. I taught myself and got the job and did that for a long time, until I couldn’t do it anymore and had to shift again.

Consciousness and expression: Music

I could remember every piece that I fell in love with throughout the course of my life thus far. Playing [Johann Sebastian] Bach was my first love. I must have been four or five. It had to be something simple from the Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach, maybe a minuet or polonaise, one of those little two-pagers; they’re all in a very simple tonality. I think it was probably the Minuet in G, if I’m being completely, unembarrassedly frank.

The big breakthrough for me was [Frédéric] Chopin. My family was Polish, and Chopin was a Pole who lived in exile like my grandparents, as he lived in Paris. That music is so romantic, and just absolutely, perfectly aligned with the oversized feelings of a young person. It’s operatic, it’s melancholy, it’s all those good things. I had many Chopin recordings when I was a kid, all of which I inherited on vinyl from my grandfather. One was Arthur Rubinstein playing the mazurkas, the polonaise, the nocturnes. But I also had an album, Vladimir Horowitz’s, I think it was called The Chopin I Love, it had all the big hits. I just listened to it over and over and over again. I remember one occasion distinctly before I was 10, I was thinking to myself, if I could play this piece the way this man plays this piece, I would give anything. I would give a leg, I would give an eye, I would give all my parents’ money. I would give my parents away. I would do anything.

By the time I was in high school, I was way more interested in more “sophisticated” music. I discovered Stravinsky and Scriabin, Shostakovich and Schönberg. At the same time, I discovered earlier music, like Renaissance music and medieval liturgical music. I became very interested, as music did itself in the 20th century, in both radical experimental music and very, very old music.

College was the moment where I discovered Glenn Gould—and Bach again, but very seriously. The first time I ever heard Bach’s second Goldberg Variations recording, I was at my friend’s house in the country. They had it on CD—CDs had just come out, it was a very exciting thing—and I was just… it was discovering God. Like it was religion. I had never heard anything like it.

I’ve played Bach through that whole time and was aware of how unique a position he occupies in the history of Western thought and art. But it wasn’t really until college that I had my religious awakening. And the truth is even now, it’s the thing that I’ll play more than anything else. I think I’ve played almost all the keyboard works at this point, which is a lot of keyboard works, including the organ works. I’ve played the Goldberg Variations for years, I played The Art of the Fugue, I’ve played all the partitas, the English Suites, the French Suites, The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book One and Two, you name it. That music is special, and not just as music. If that’s the only thing that man ever made—and by man, I mean, all of us—I think we could be proud of ourselves.

So for me, Bach is God. In all the art forms that I engage in, I’ve never encountered anything so profound, that sounds like and feels like the texture of consciousness at the deepest level. And I don’t think it’s something you can do in design. I’m pretty sure it’s not something you can do in painting. Literature can come close in some ways, but I even think literature aspires towards the state of music.

Unveiling language and its mediations: Philosophy

If all of our thinking that we can communicate and transcribe is mediated by a form, the form of language, then how are we ever going to understand anything if we can’t understand how that mediation works? The idea of understanding language is primary for me, and Ludwig Wittgenstein was my guy.

I discovered him in college. There’s something so romantic about Wittgenstein as a character. He’s so handsome, he was so talented in so many ways, he had this massive fortune that he renounced, he built his own log cabin in Norway. He volunteered to fight on the frontlines in hand-to-hand combat in the First World War when he was already a.) living in a place where he didn’t have to, and b.) was a member of the aristocracy and absolutely didn’t have to. On top of that, he wrote these almost crypto-scientific treaties where all the propositions are numbered, like his first book the Tractatus; his thinking was so neat, meticulous, and atomic. There was just something deeply sexy about him as a thinker.

Wittgenstein was like a romantic hero of some kind. Glenn Gould also definitely preferred his own company to other people’s company. There’s something monk-like about people who remove themselves from the world to do their chosen work, and that was very glamorous to me when I was a teenager.

Friedrich Nietzsche is someone I came around to later in life. He is a truly interesting mind. He’s also a musician, by the way, and a poet. He really wanted to be a composer; his idol was [Richard] Wagner, which is a huge mistake on his part. In fact, he showed his music to Wagner and was sort of slapped down, unfortunately for him. But we have music of Nietzsche’s that every now and then gets pulled out and performed.

I’m not sure I love his music, but it’s interesting. What I love is that he wrote philosophy that was fiction, that was parable, that was poetry, that was music. I like that he expressed himself in all of those forms and considered them all valid.

From aural to visual orchestrations: Design

I had just finished graduate school. I was teaching an orchestration class at Juilliard. I was cobbling together little bits of money here and there from performing, but altogether needing more money. Most of my time was being spent composing at that point. and I was composing these very grim, joyless little works of experimental music. I wasn’t happy, the people listening to them weren’t happy, it was just awful. I was throwing my soul into it, I was working day and night on this stuff.

This sounds very nasty, but the truth is that my first experience with design, the experience that told me that maybe I should investigate it, was the feeling that I might be able to do it better than somebody else. It’s embarrassing to admit, but it’s true.

The first time I ever saw the process of something designed, it was a CD package for a piece of music I had written. The designer was working on it, I was standing there and I remember thinking, what are you doing? That’s not how you do this, this shouldn’t look like that. And I remember keeping my mouth closed, but thinking like, why is he making those choices?

I didn’t know anything at that point. I didn’t know what the programs were, I didn’t know what the parameters were, I didn’t know what the job description was, I just knew that I wanted to, like, grab the mouse out of this person’s hand and start moving it around. So maybe that’s love, I don’t know.

A couple of months after that, my wife was like, you know, there are graphic designers. That’s a thing. And you like to read. Maybe you could design books? You could think about that. And I was like, people don’t design books, what are you talking about? I’d had a million book covers in my life at that point in various ways, and I just never noticed them.

So the first thing I did was actually go to another record label that I had done some work at, and just said, like, I know, this is crazy, but I’m interested in this new thing: design. Would you let me try my hand for free at doing some packages, posters or whatever for you guys? And they were like, yeah, we don’t care. Go ahead. I think they thought they wouldn’t like any of them.

This was before the internet, so the way I got those things done was by buying every book on design that I could, many of which were how-to books, like for Photoshop and Quark. I learned how to use the software, and I looked at a lot of stuff. I just looked. I started looking, and had notebooks to keep track of what I was seeing: what looks good, why does that look good?

In the end, I did 15 or so projects with them, and by the time I was done, I had a portfolio. And then I got a really lucky break: it’s such a tenuous connection, but my mother’s friend’s Scrabble partner’s boyfriend was Chip Kidd, who’s a book cover designer. And so through that weird chain, I was able to go into Knopf with a book of my weird self-made work for this record label and talk to Chip.

Chip was very generous with me. I didn’t really know at the time that he was the most famous book designer in the world. (He might still be, I don’t know, I’m a little out of the loop.) We’ve joked about it since: Chip was like, Oh God, I have to do another favor for a friend; I was like, I gotta go talk to this guy, but I really don’t think it’s going to lead to anything. We just really liked each other.

And yet, there was no job available. But just down the hall was a paperback publishing company called Vintage. Chip brought in the art director from Vintage: John Gall, who is now the art director of Knopf, where Chip works. I talked to John for a while. When I got home, my wife was like, how did it go? I just said, oh man, I want to work there so bad.

John called me a week later: I don’t think we have anything, I’m really sorry. That week, I was so bummed out. Five days later he calls and says, You know what, somebody’s leaving. This was just after 9/11; there’ve been a bunch of bomb scares, people were leaving New York City in droves, among them one of the designers at Vintage. If you want the job, it’s yours, John tells me. I think it paid USD 35,000 a year, which is really not something you can raise a family on. But I was skipping to work every day. I was happier than I ever had been.

Peter Mendelsund’s written works (The Delivery published by Macmillan Publishers)

Textual engagements: Writing

The writing just happened because honestly, I’ve sort of always been writing. I had to write in college, but the idea of doing it more seriously really came from having a blog.

When I was working in-house, I just started this blog, Jacket Mechanical, about my experiences as a book cover designer, my thoughts about the books that I was working on, my thoughts on design in general. It had a little audience, and I really enjoyed it; we were all vibing together as designers and it felt great. It got me used to just putting words into the world daily.

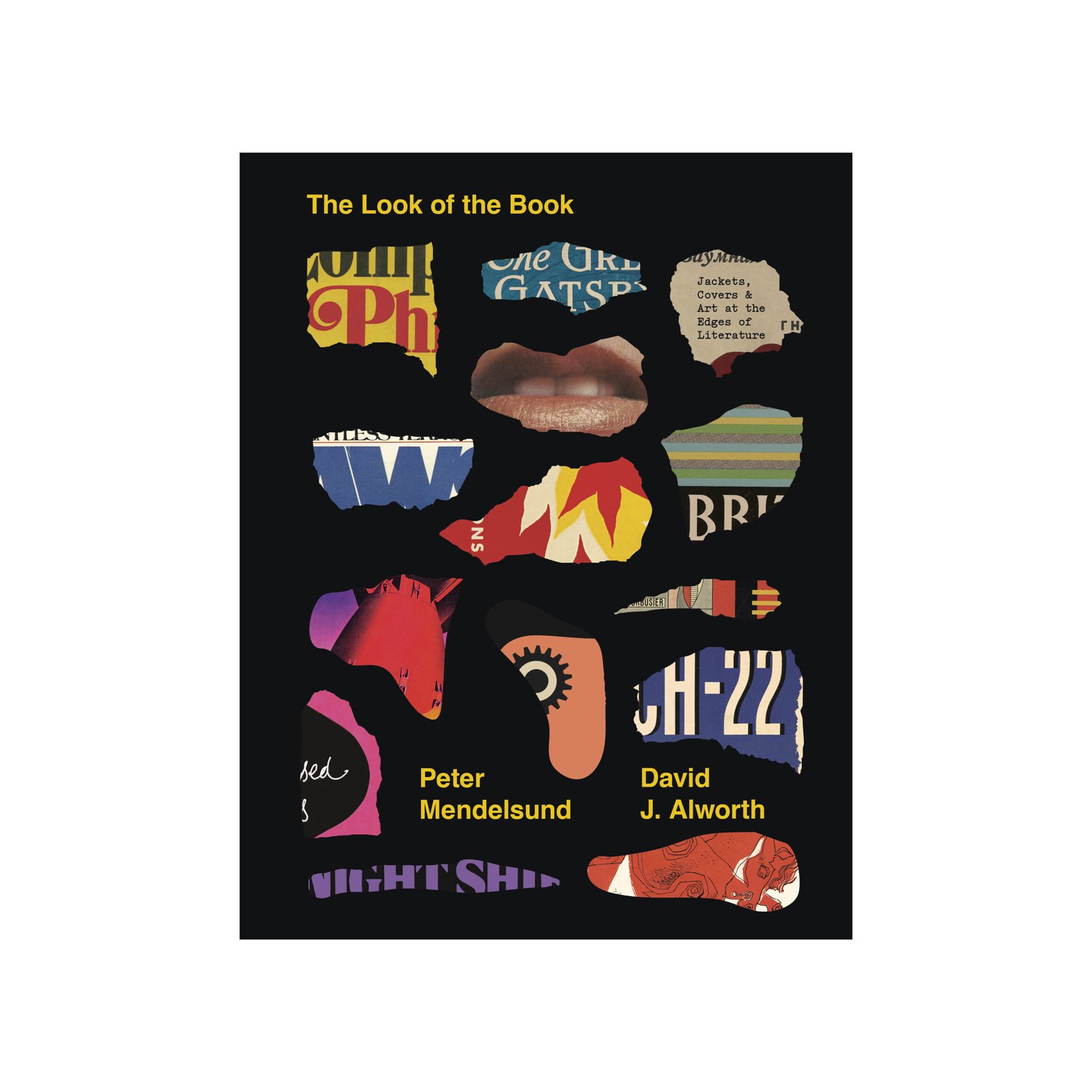

I had a conversation with a friend one day, I think this was 2012, about the imagination when you read. It sparked something. It made me want to write something about what we imagine when we’re reading books. And that became What We See When We Read. As it happens, the publisher had asked me that same year about whether I would be interested in doing Cover, a book on my own work. Both of those books had to be put together in about a six-month period. It was exhausting. I had to do it on top of my day job, and they both came out on the same day. And I guess I just caught the bug. It was really fun.

When you’re writing a book, it’s so different from designing in the sense that it is yours uniquely. It’s not dependent on any commodity or sales channel. People can not like it, but they can’t tell you to not write it. This is yours, it is a universe that you are creating yourself. After those years of being an in-house designer, and being kind of beaten down, it felt so good to make something that was purely mine.

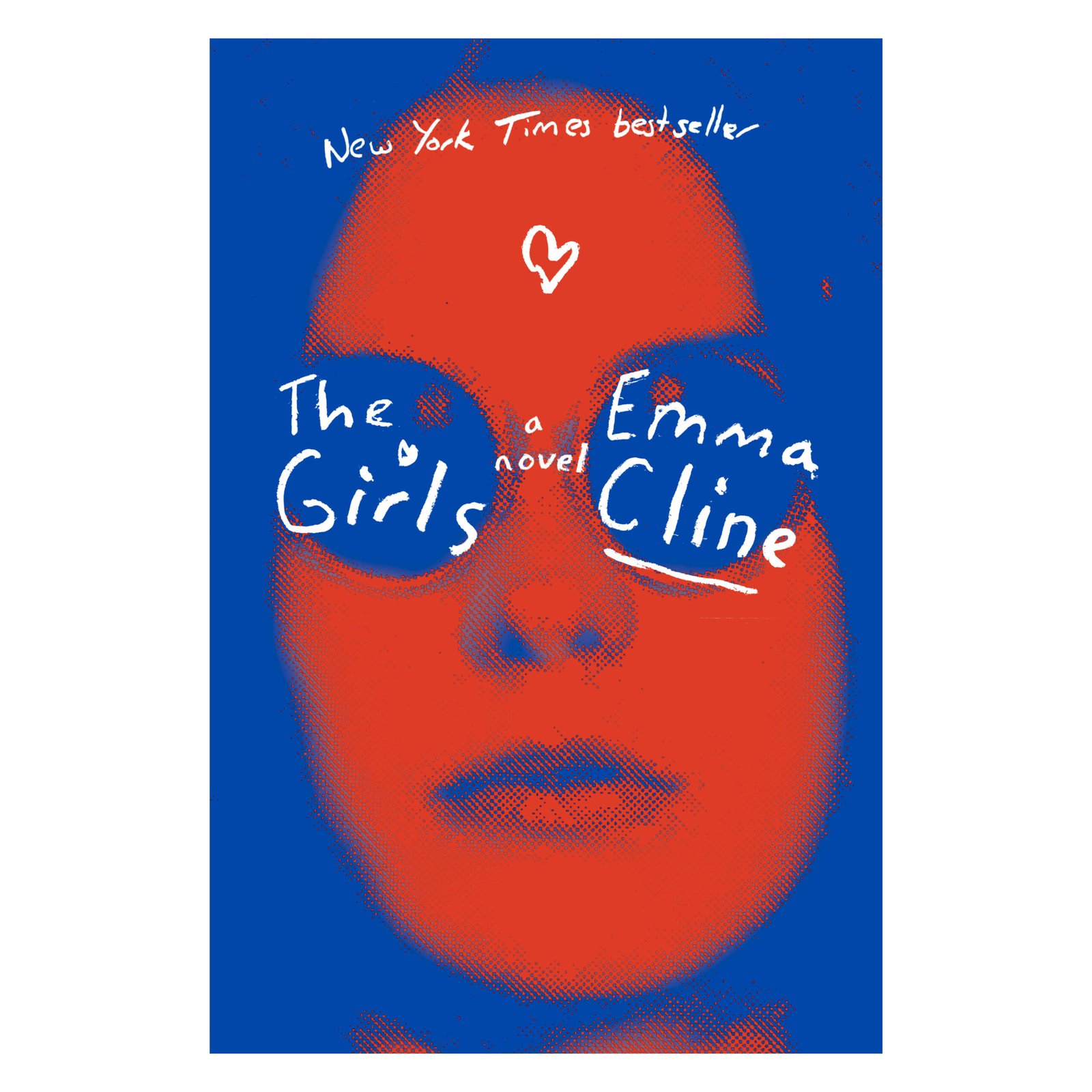

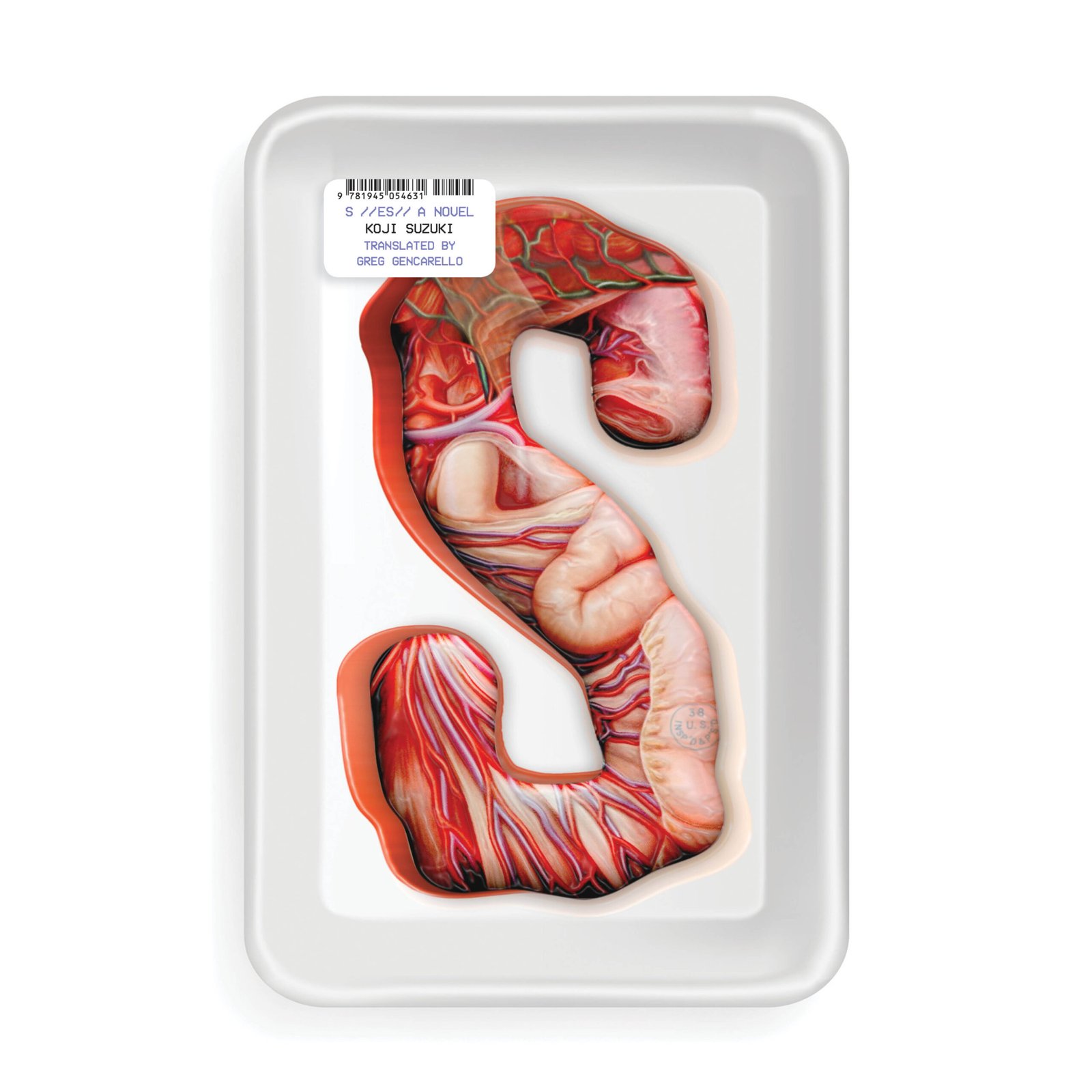

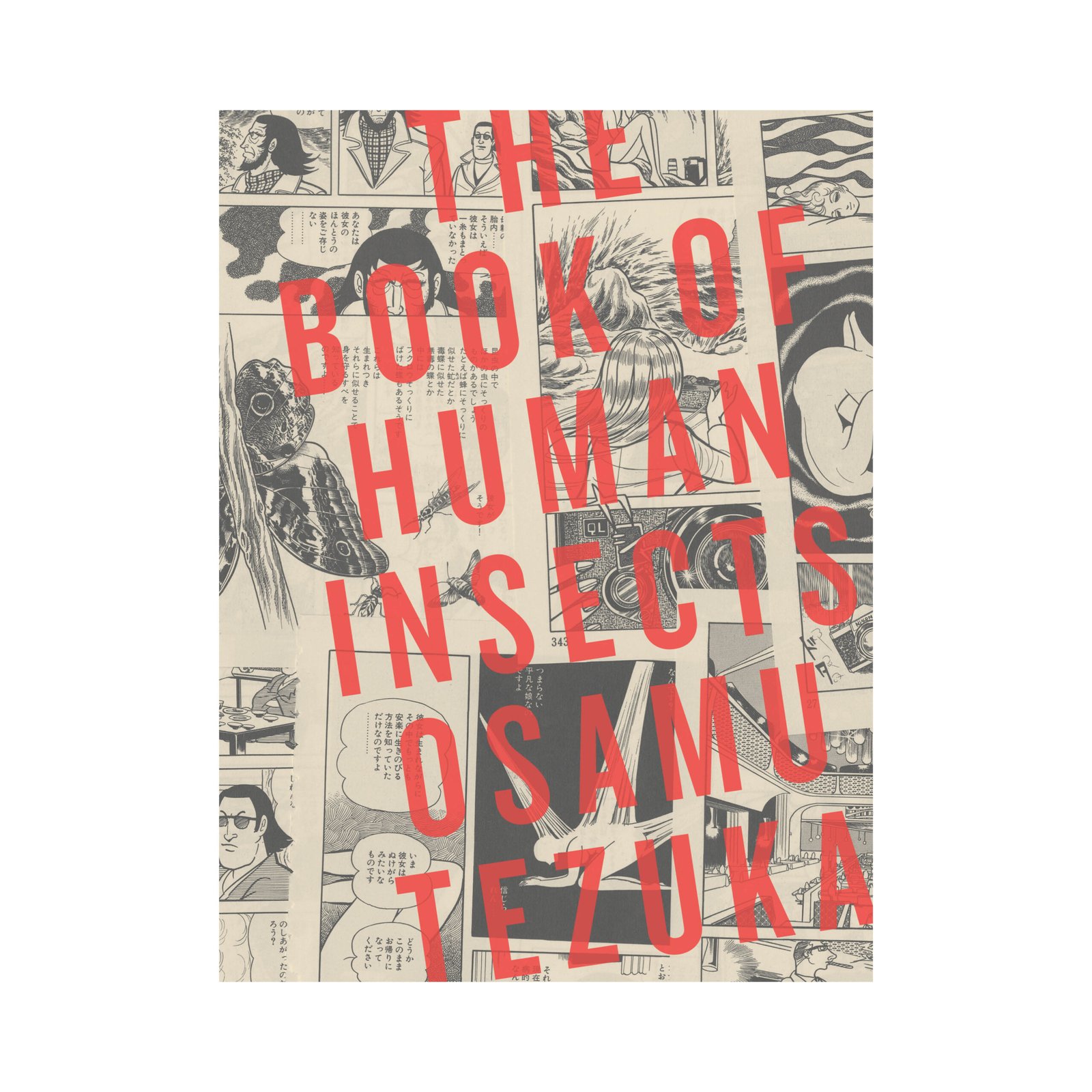

I’ve always been interested in fiction, so the novel came next (Same Same), and then the next novel came (The Delivery), and then the next book on design came (The Look of the Book). I’m about halfway through a new novel right now, although I’m finding it hard to write. I’m just trying to keep busy.

Muscle, pigment, canvas: Painting

The pandemic has been hard for everybody. I’ve had friends who were very sick, and obviously, there’s been a tremendous loss of life. But for me, personally, I’ve been very lucky in many ways. One of them is that I’ve been able to entertain myself, while alone and indoors. And I have a family that I love, with two teenage daughters.

I think it’s been less hard for me on some level, because a lot of the things that I love doing, the disciplines that I’m engaged in, I already do at home alone. I was a classical pianist until I was in my 30s, and since I was a little kid, I spent a lot of my hours every day alone at the piano. I’m a reader, and I’m a writer; those are also things that you need to do perforce by yourself. So I’m used to a certain amount of solitude.

Now, I’m really interested in painting. Mainly because it gets me out of my brain—and I’m a little tired of living in my brain. It’s much more physical and gestural, it gets you outside of yourself. It’s good for me—both as a person and as someone who makes things—to step away from society every now and then and focus a little more on the work. I do a lot of socializing under normal circumstances. I live in New York City and I work at a magazine, and there is a lot of interesting people, a lot of very smart, creative, and talented people—a lot of whom you have access to. It’s very tempting to be out all the time, meeting new people all the time, engaged in new projects all the time, and it can get both distracting and exhausting. The pandemic for me was really a moment to go inward a little bit.

I’ve been painting a lot this year. As soon as I started painting, I started seeing paintings everywhere. My eyes in my brain were sort of readjusted towards the world, and all of a sudden, the world became available to me as a series of paintings. The first painting I ever made is actually this blue one, which is fairly large. That just really happened because of the pandemic, and I was depressed and didn’t know what to do with myself. Somehow, me and my family found ourselves in a rural area where there was a big barn, and I thought, this is a great place to paint. And so I did. That was about a year and a half ago.

When life sort of presents me with an obstacle, I tend to get very mopey and depressed about it, then very angry and upset. At some point, I get tired of being upset, and something clicks in. And I realize I just need a new project.

A multiplicity of paths

I mentioned that being out in society and culture a lot can be very stimulating, but also overstimulating and distracting. But conversely, I think that there is something to be said about working multiple jobs at the same time, in multiple media. I have found that it keeps you from getting too locked up, it keeps you sort of free, and loose, and relaxed. Especially if you’re able, within a day, to go back and forth between designing something and painting something or writing something or playing something, there’s something about it that lubricates the machinery and keeps you active and loose, and you tend to not get too neurotic about one thing.

When you’re doing creative work, some of that work is muscular. What I mean is some of that work involves work, like you have to dig down, try things, throw things away, and think. It’s very linear in that way. And yet a big part of it is mysterious and happens in the background. In order for that part to work properly, you have to be able to step away from what you’re doing. It’s like when you’re trying to remember a name and you can’t, you think about something else, and then you’re in the shower and it comes to you. Your mind is constantly working on what you’re working on, whether it’s your conscious mind or your unconscious mind. I find that when you’re working on lots of things, you can step away from something, and then the solution will just almost magically or mystically come to you.

I’ve definitely worked in a lot of different media, and the idea of being multi-channel is very important to me. As interesting as book design is, there are other things too, and they inform one another. Certainly, if you’re a designer, I think it behooves you to also be a reader, writer, and communicator in all kinds of different ways.

I guess I’m one of those people who feels like everybody has at least one but probably multiple paths that will be incredibly satisfying for them to discover. One of the sad things in life is that often, we’re steered in the wrong direction, or—for reasons that are either economic, social, or cultural—we don’t get a chance to come into contact with that thing that can spark our interest.

At a young age, you have to learn how to do the work, put in the hours and sweat, and be faithful to the project; it’s important to learn discipline, that’s crucial to anything you do no matter what you end up doing. But equally important, I think, is just the willingness to try new things, new tastes, new flavors, see what sparks your interest. I always tell my daughters: your schooling years are the time in which you just have to be table-hopping and trying new things. Be willing to try something, and then put it aside.

In the 21st century, we’re very focused on this idea of our selfhood being predicated on our occupation. The genealogy of this goes as far back as capitalism and commodity. It’s dangerous, because—and this is something I come across in my own life—I think people find it difficult to figure out how to approach somebody who does multiple things. There’s this idea that if you do more than one thing, you’re an amateur at all of them. And yet there was once an idea in Western culture, sometime in the Renaissance, that a cultured person was somebody who experimented in this way. It’s something that I believe in very strongly.

It’s important to uncouple your idea of who you are from what you do. Your job as a human being is to be curious and active in that curiosity, and try as many things as you can. Some of those things are going to be left by the wayside because they won’t turn out to be that interesting to you, or you may not become proficient, or will just prove too frustrating or difficult. But some of them, it’s going to be great. •

Watch the interview in video format below; we’d like to thank Karl Castro for the production of this video

Kanto would like to thank Honey De Peralta and Keri Horan of Penguin Random House, with the assistance of Angel Yulo, for making this interview possible.

Karl Castro is an independent artist and designer. His body of work straddles the fields of art, cinema, and design, with a view of their interaction with history and social consciousness. His design practice focuses on editorial design and creative consultancy, working primarily with cultural institutions, independent artists and publishers, and university presses. His book designs have won several Philippine National Book Awards, and he has mounted solo exhibitions at the Ayala Museum and Vargas Museum. He is a lecturer at Ateneo de Manila University’s Department of Fine Arts.