Interview John Alexis Balaguer

Images Jake Verzosa, courtesy of Silverlens Galleries

Most contemporary artists would shy away from making art revolving around indigenous cultures. Not only is representing another’s culture and traditions prone to appropriation but speaking about another’s communal identity carries a social and ethical weight not everyone can carry. The likes of Santiago Bose from Baguio whose mixed media works responded to western assimilation, and Norberto Roldan’s curatorial projects involving communities, were vigilant in their artistic portrayals and efforts of indigenous or regional resistance by way of their art-making and community organizing. More recently, Archie Oclos’ large-scale paintings and murals depicting indigenous figures in instances of sacrifice are empowering more artists and art enthusiasts to be involved in recognizing and commemorating our local heritage.

On May 27, Makati-based art gallery Silverlens opened the online exhibition The Last Tattooed Women of Kalinga by photographer Jake Verzosa (b.1979) in its Viewing Room. Born in Tuguegarao, Verzosa used to be afraid of the sight of the tattooed townsfolk from the Mountain Province whose reputation as head-hunters were demonized by colonial conquerors. Since 2009, his photographic project aimed to “create something that is connected to his place of origin” as editor Jerome Gomez states in the essay accompanying the exhibition. More than ten years after the onset of this personal intention, books compiling the photographs have been published, and local and international galleries and museums have since exhibited his works.

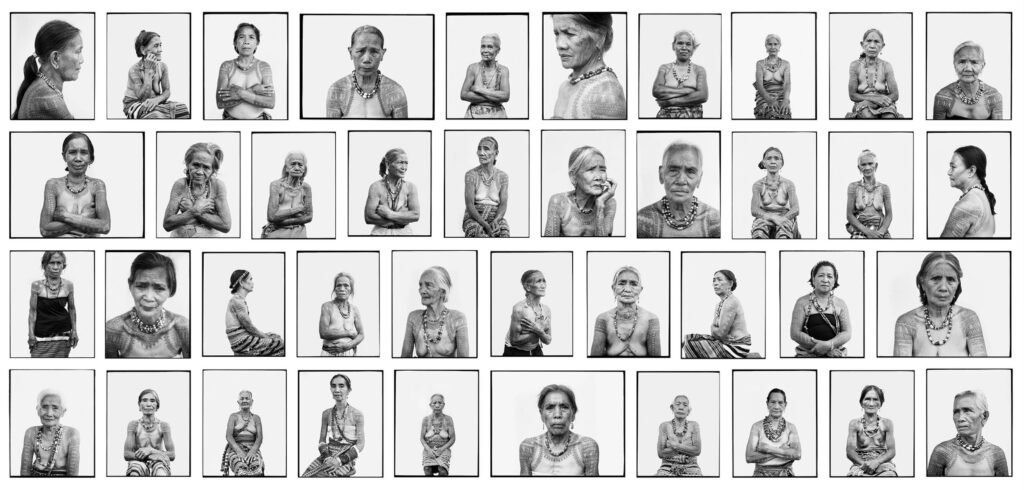

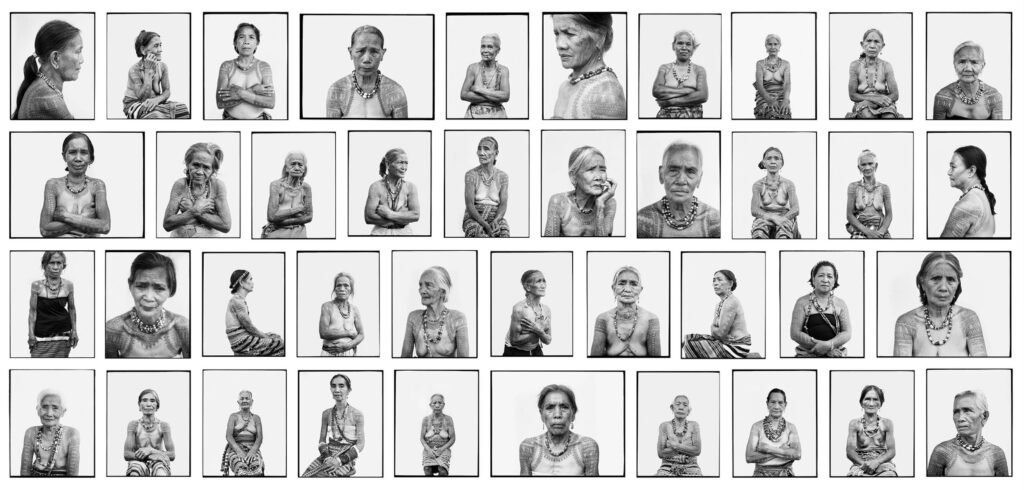

At the onset of the pandemic last year, however, most exhibition spaces had to be closed off to limit visitorship in enclosed spaces. Viewing Room was the response by Silverlens. The Last Tattooed Women of Kalinga is the latest iteration of Verzosa’s series of black and white film photographs depicting the bare skins of the traditionally hand-tapped tattooed women of the Cordillera Region. The online exhibition which ran until June 17, 2021, gathered the set of forty black and white portraits, photo and video documentation, and textual narrative by Gomez onto the online sphere— a space nuanced in itself due to it being commonly used locally as only a marketing tool by art institutions, and only recently an intended space for exhibitions.

The exhibition of portraits alongside its process gives attention to the art-making effort and the identities of the tattooed women whose communal traditions are immortalized between body and memory. It records the artist’s photographic process from immersion to illustration of an embodied heritage endangered. In a way, Verzosa’s exhibition highlighting both portraits and artistic process is in itself a reflexive exercise—the archive of documented images and narration retraces the history of the project and reveals the unseen aspects of his art-making. After all, the tedious immersion, research, and unique goings-on ultimately contribute to the final portraits, yet they are usually unrecognized. We might therefore attempt a review and criticism in a way that recognizes the contexts by which the works and archive are virtually exhibited. As one opens the online exhibition, black and white portrait photographs of the tattooed women from Kalinga are lined up in rows, each framed in black borders reminiscent of cinematic film stills.

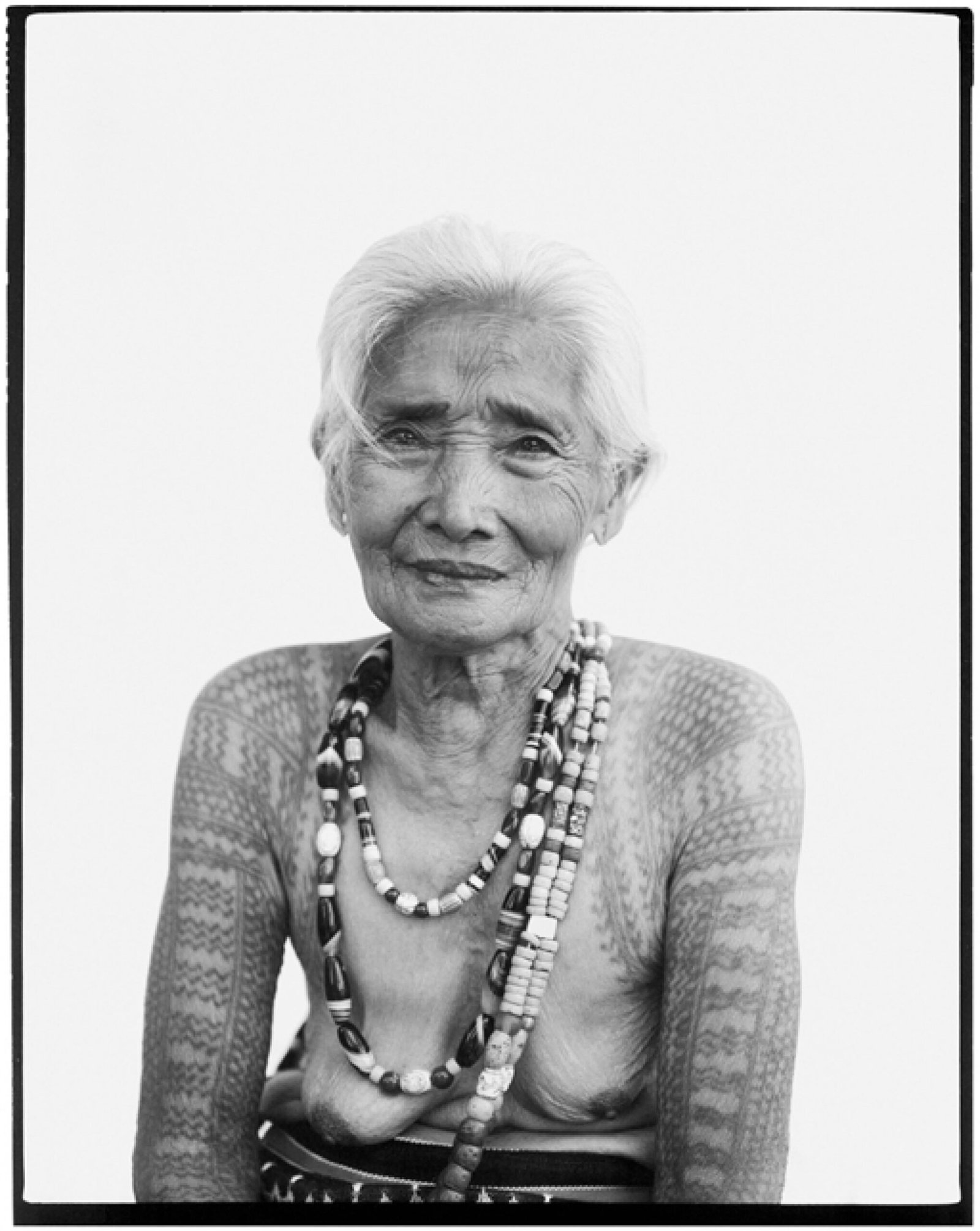

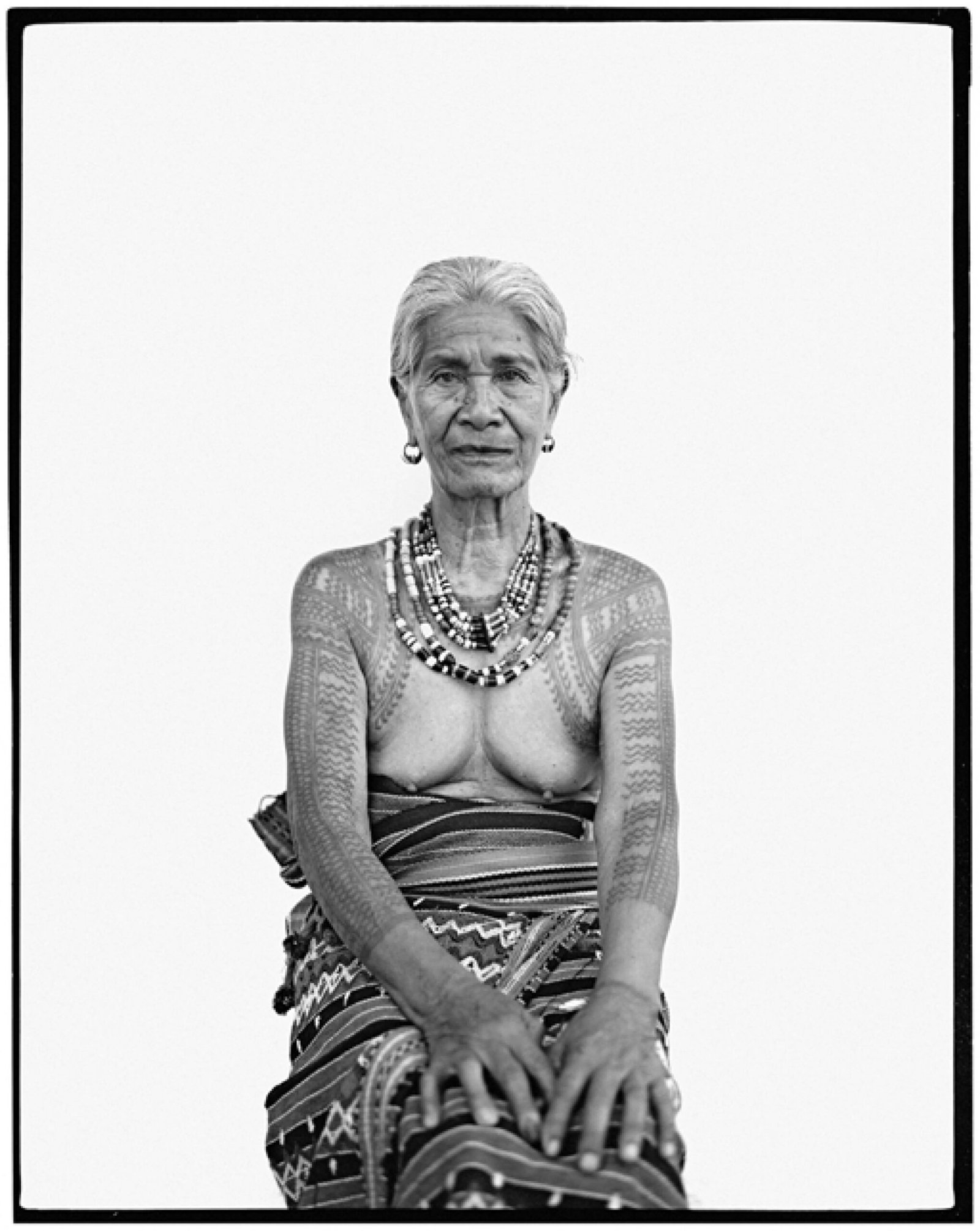

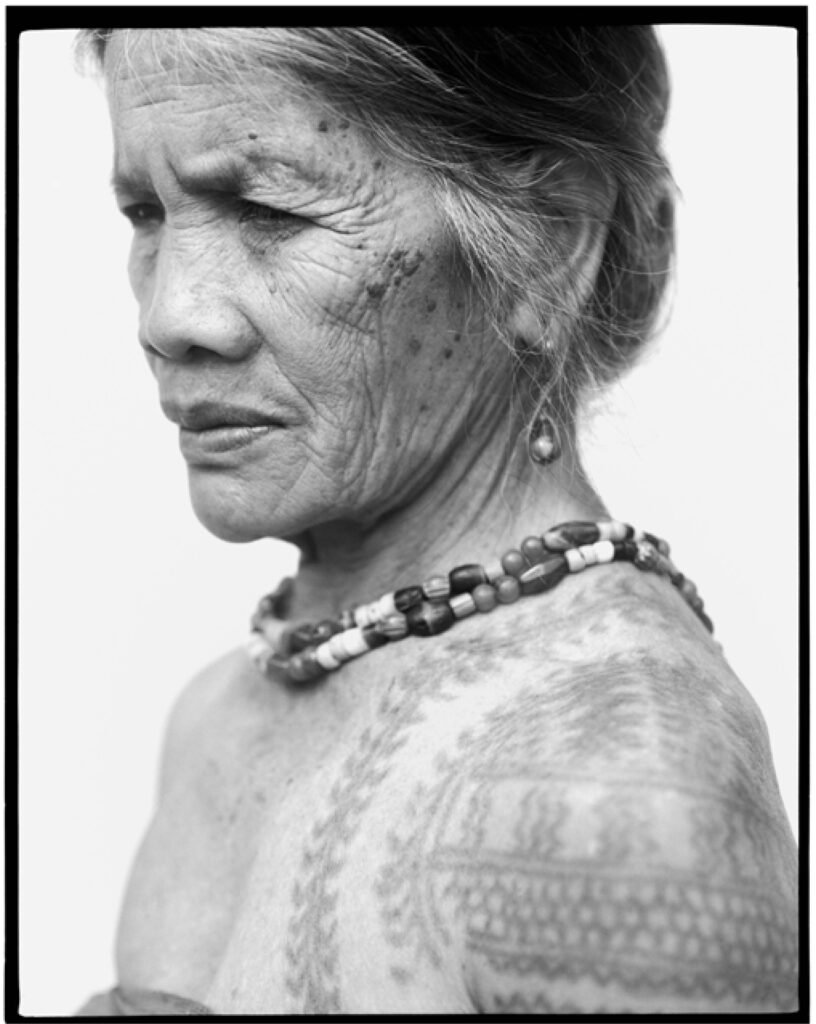

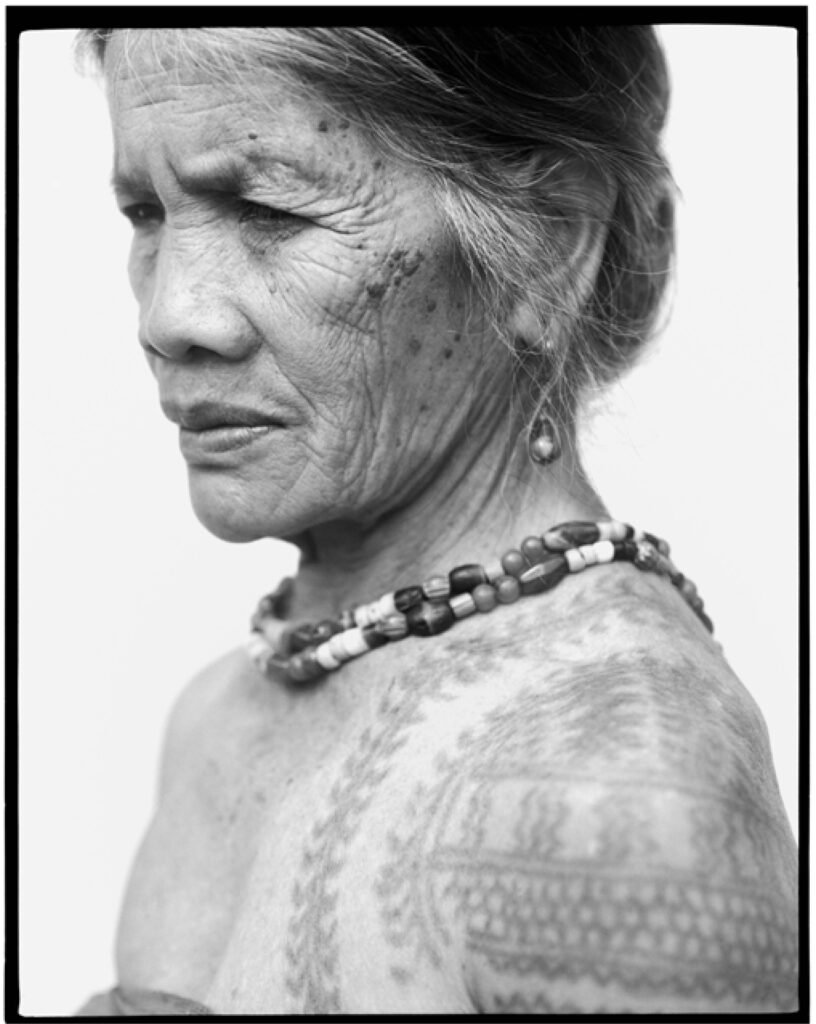

The women are captured in front of a clear white backdrop, from knees or waist up, in profile, or bust, to lead our eyes to the forms in focus—their tattooed skins. Inked with figurative designs of animals and landscapes including grass (inal-alam), stars (tinat-araw), centipede (ginay-gayaman), and the ladder (tey-tey) among many others, and combined with geometric motifs and patterns, the composition and cropping of each photograph almost negate all other visual elements to give attention not just to the heritage embodied, but also the evidence of age and subjective experiences on the women’s emotive facial expressions. In the center of this compilation is a portrait of Fang-od Oggay—hailed as the “oldest” tattoo practitioner (manwhatok) in Kalinga. Hailed years back as the last remaining manwhatok of the community, she has since passed down the hand-tapped tattooing practice to his grand-niece, Grace.

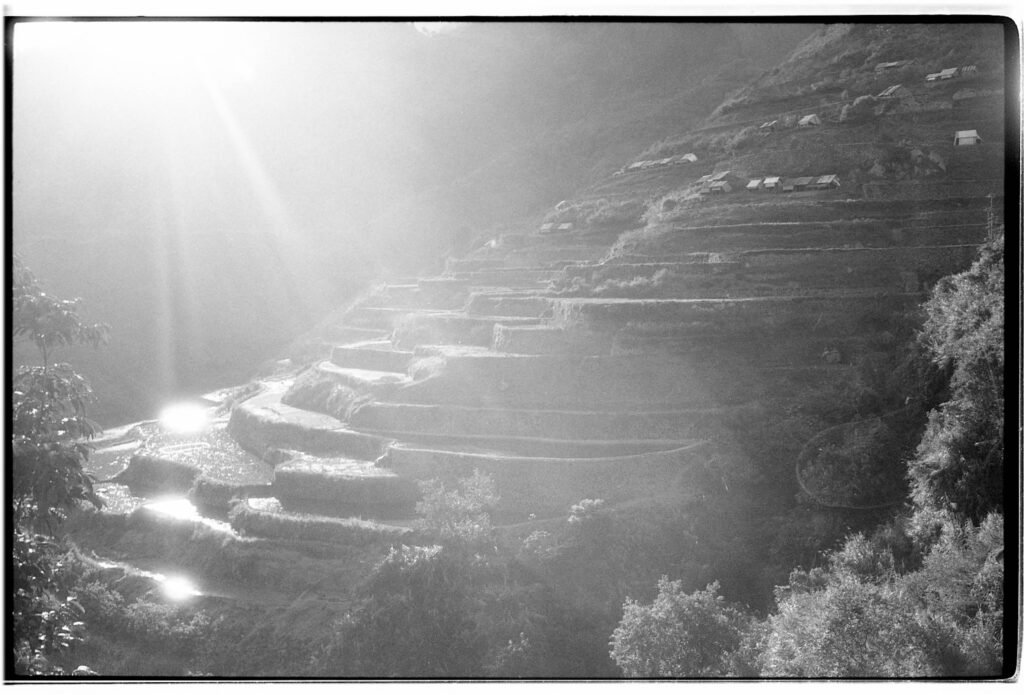

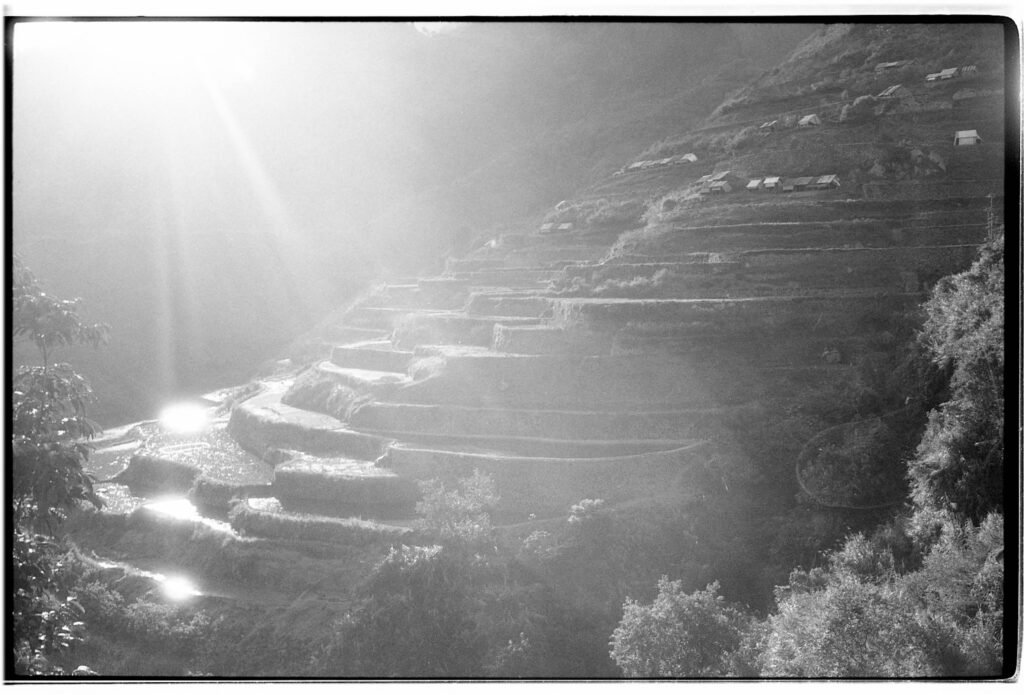

Further into the exhibition, film images by Verzosa accompany Gomez’opening text depicting the landscape of the Mountain Province as geographic context.

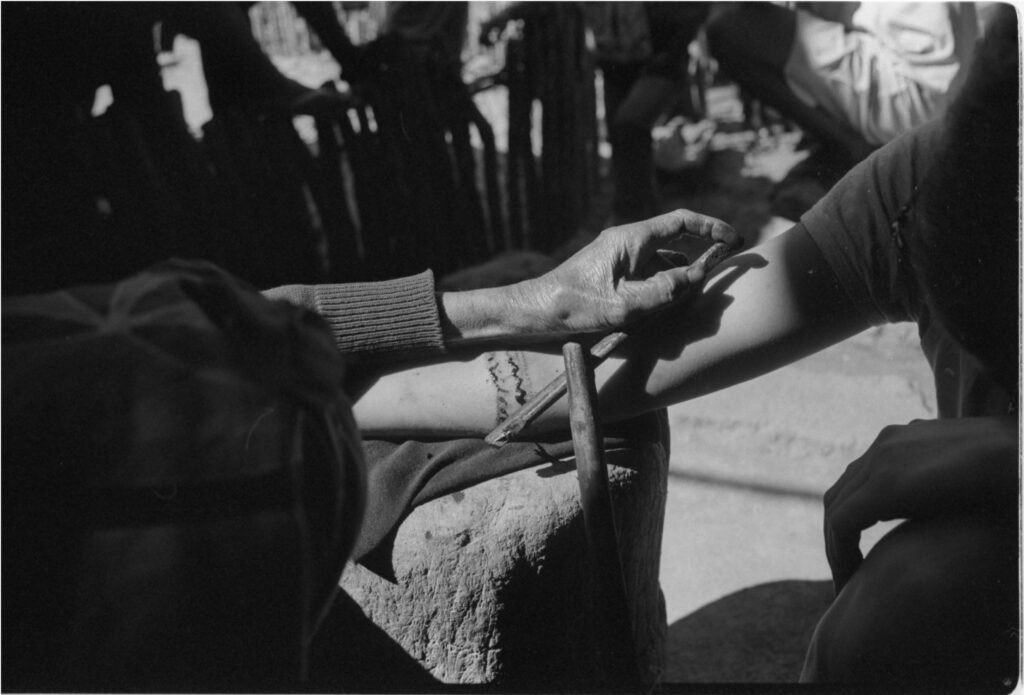

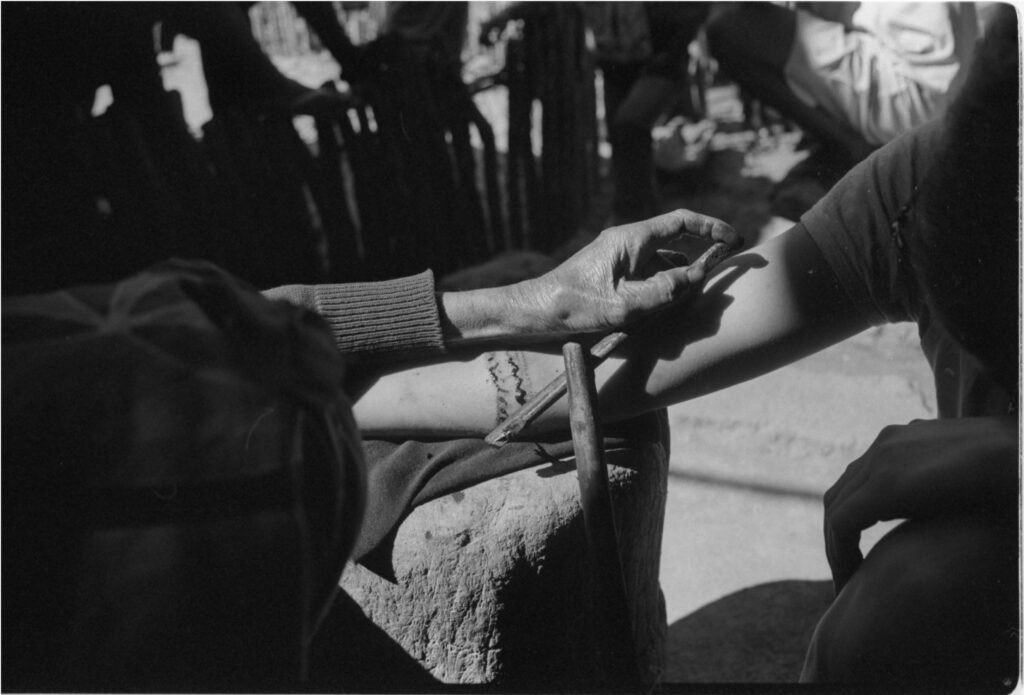

Four documentary photographs can be seen, laid out: the image of the paddies of rice constructed as terraces shimmering in the sunlight is larger and positioned above three other images: farmers working amongst the field, and young boys in quotidian work and play. The arrangement, while it sets the geography of the project, might hint at a subtle connotation, of man’s relationship with nature: in each of these images, the hills are seen constantly watching over in the background. While in the villages, Verzosa’s photographic process would include an immersion with the community by living with them for a week before taking their portraits. While he is the other in this respect, living with the community assumes a development of respect or understanding of a way of life not similar to ours. For another two or three weeks, Verzosa would then take his photographs. With only a Pentax 67 film camera, tripod, and a white backdrop as tools for his makeshift studio, Verzosa had only about twelve shots for each of the women. The extensive procedure allowed for natural conversations, curious questions, and organic connections to pop up. In a photograph in the section, Verzosa is seen taking snaps of Abonao Sicdawag seated with her feet propped up on a beer case, the white backdrop roped up.

The image reveals how the photographer frames the subject for the final portrait. More importantly, the photo also captures the world outside the frame—the women around the scene, some resting or waiting for their turn, the façade of the homes they lived in, and the community of persons whose lives continue behind the frame. The single image effectively introduces the tension between the journalistic vis-à-vis artistic aspects of Verzosa’s project.

As one scrolls further down the exhibition, images of how the portraits were exhibited in numerous art galleries, museums, and institutions in a number of countries including Japan, France, Canada, Germany, and The Philippines are compiled in a slideshow. In one image, a number of people gather around a blown-up digital print depicting Bogkayon Suyam in Merignac Photographic Festival in France (2017). In this portrait, Suyam is captured from shoulder to forehead, but more than her surface skin, one might recognize a glimpse of emotion in her facial expression pensive, pondering. Her earring, beaded necklace, and tattoos reveal their shapes and textures in the black and white chiaroscuro, further reminders of markers of achievements she wears. While we do not know much about Suyam with this photograph alone, the image Verzosa captures of her immortalizes an instance that carries her experience.

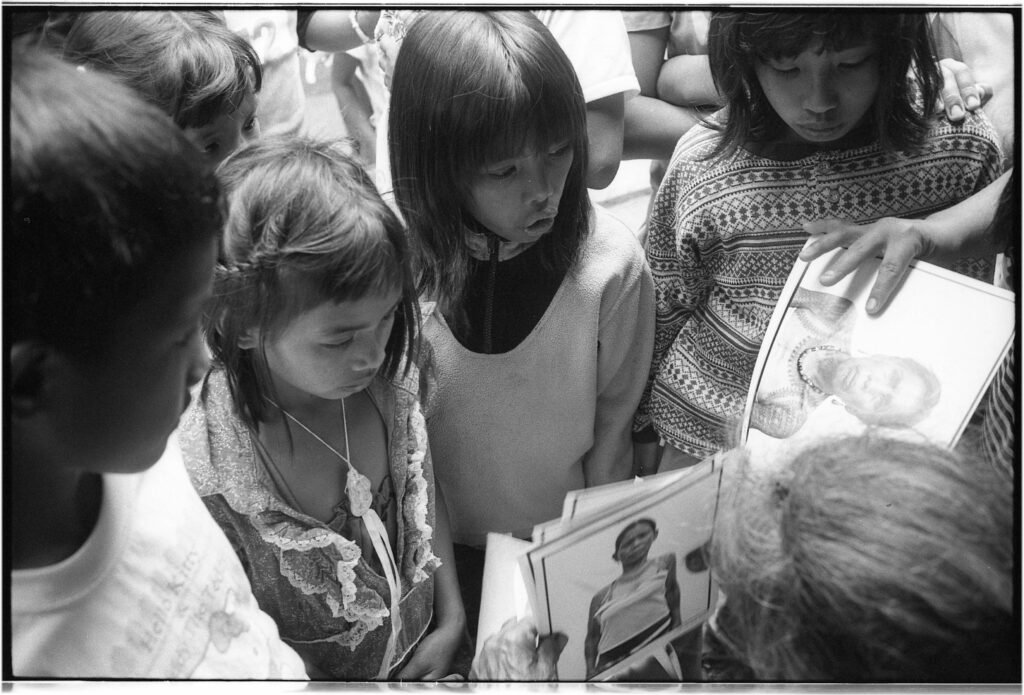

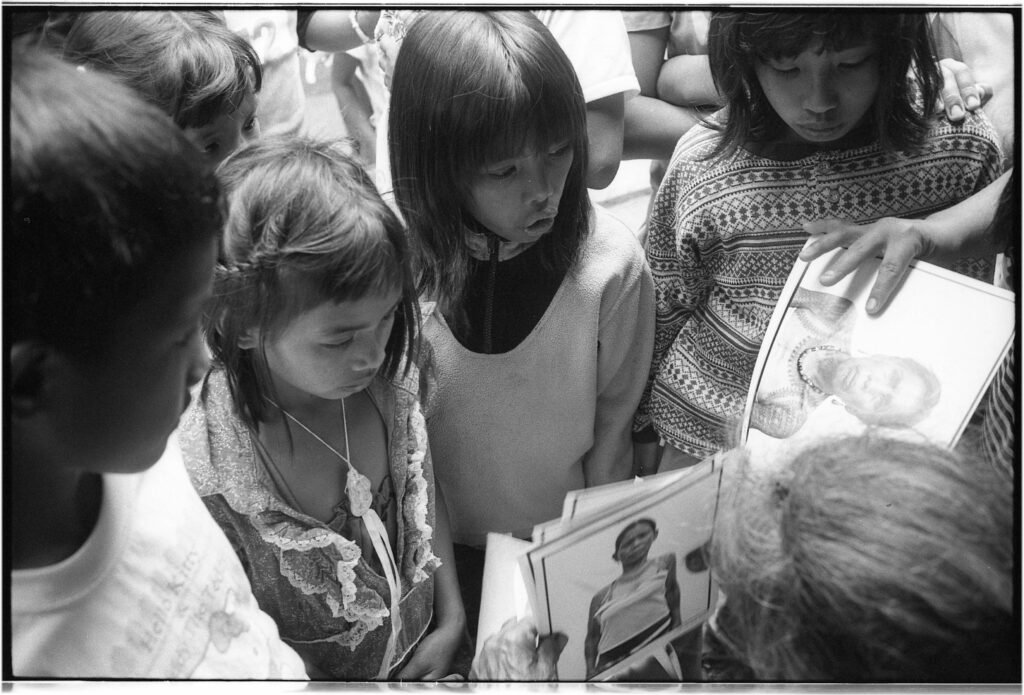

However, the removal of the image and subject from its setting, and public presentation as art in an institutional exhibition, let alone a foreign museum, might also introduce nuances of the dynamics about the viewer-and-viewed, a common tension in Verzosa’s series. It is, however, addressed: alongside the slideshow of images of local and international shows are some photographs of the women receiving their own copies of Verzosa’s works of them. In one image, a group of children is gathered around Karina Suyam surveying a print of her.

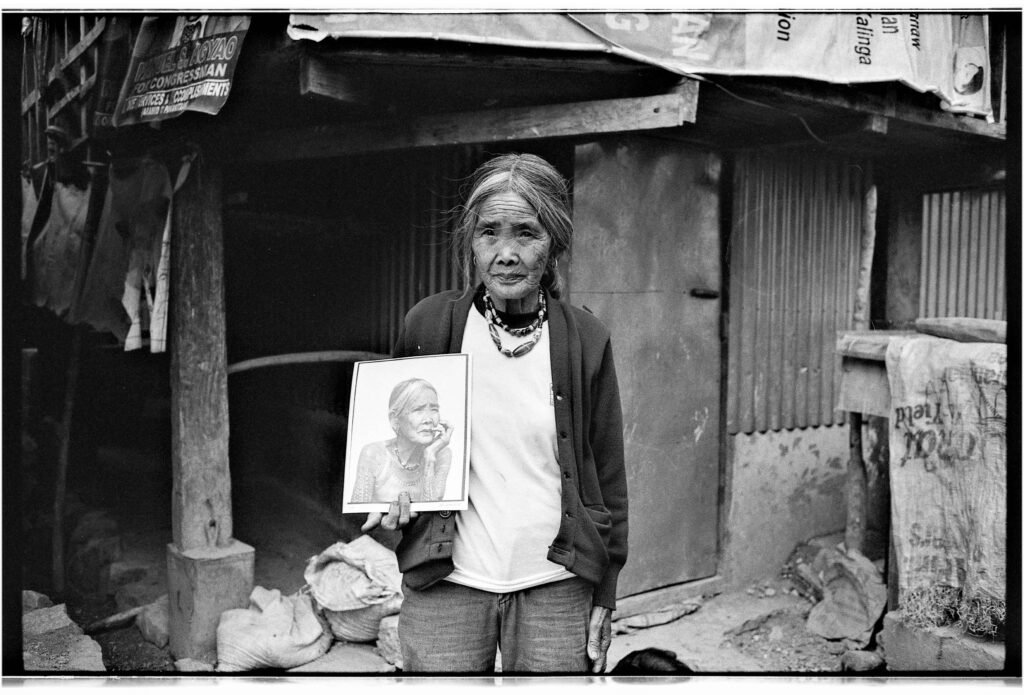

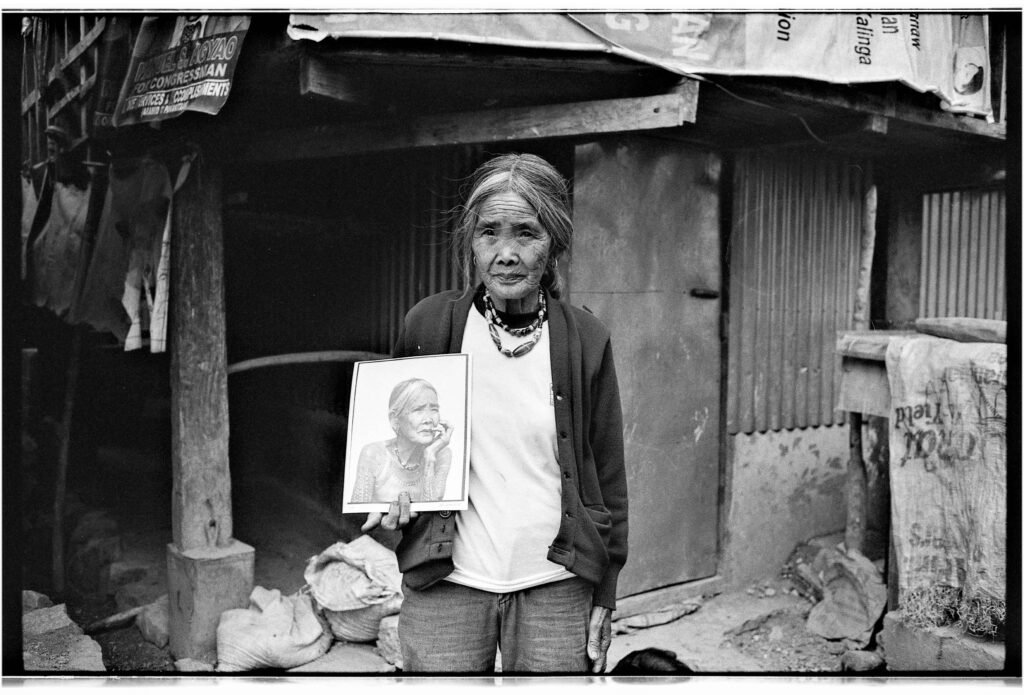

Today, most might argue about what femininity or beauty looks like, especially in the exaggerated bodies and faces perpetuated by modern commercialism. In the traditions of the Kalinga (and other indigenous groups, prominently in the Visayas), men and women had their bodies marked with tattoos since pre-colonial history as standards of beauty, and markers of status. The conceptual contrast the image creates remarks a hope that the next generation might find appreciation if not pride in the traditional aesthetic values. In one image, manwhatok Fang-od holds a copy of her famous profile, an archival pigment print on Hahnemühle paper now popularized as Verzosa’s oeuvre from the series.

Fang-od is seen in front of a humble house, wearing a shirt and jacket—a graphic contrast to the image of her in her hand: her, adorned by momentous tattoos covering her arms, shoulders, and collar, she rests her head on her left hand with an intense countenance one might describe as anxiety or concern. The image itself launched Fang-od to iconic status in social media, but the person in the famed portrait and the person holding the portrait are one and the same. Gomez’s section essay further into the exhibition notes that in 2017, the manwhatok was invited and agreed to a two-day live hand-tap tattooing session, and speaking appointment at a design trade fair in Manila. However, a viral snap of what seemed like an exhausted Fang-od in social media raised discussion of the exploitation of the artist, and the commodification of culture. Verzosa’s portrait within a portrait signifies this exact challenge and tension: at what point does photography capture, and at what point does it recreate?

Finally, the exhibition presents the forty portraits from Verzosa’s 2011–2013 series as a full set. In the image depicting Kannao La-ib, Verzosa takes a front shot of La-ib with her arms crossed, showing her tattoos from shoulders to the length of her arms.

For Lacdag Awingan’s portrait, Verzosa’s image shows Awingan adorned with large beaded necklaces, and her tattoos sharp against the light. There is a hint of a smile in both women’s portraits as they show their tattooed patterns and figures.

Lacdag Awingan, 2011, digital C-print on Hahnemühle paper, 25.25h x 19.50w in • 64.14h x 49.53w cm, Artist’s Proof 2 of 3

Abonao Sicdawag, 2011, digital C-print on Hahnemühle paper 25.25h x 19.75w in • 64.14h x 50.17w cm, Edition 3 of 5, Image courtesy of the artist

Because the art is heavy with the weight of a centuries-old tradition and the biographic history and communal achievement of their wearers, Verzosa’s straightforward photography allows for the persons to be captured not in their entire complex humanity (no one could hope to capture this immensity, especially as a mediator), but instead as a complex person in an authentic instance.

Photography had not always been used simply as an artistic tool in its history. In the early 19th century to early 20th century, photographic images of colonially-assimilated peoples and natives were used as a political tool, serving the gaze of conquerors and framing natives as “other” oftentimes as objects of study in anthropological or territorial contexts. The act of representing someone else’s identity, by another person, falls to the framing hands of those with the power to code a message. This almost always resulted in violence and control. An oppressive technique disguised as scientific was used to compare or contrast the “civilized” and their “collections.” When I was an educator at the Ayala Museum, I chanced upon a digital print by Malaysian visual artist Yee I-Lann, titled Study of Lamprey’s Malayan Male I & II (2009) a reaction to John Lamprey’s Front & Profile Views of a Malayan Male (1868) which portrayed a Malayan man in the nude standing on a platform against a grid-like background. The man was originally photographed in the front and profile angles as if he were an object to be measured, labeled, and studied, devoid of any complexities or human agency. I-Lann’s artistic reaction crops the man out of the composition, and she replaces herself outside of the measuring lines, studying the space that was left by the man’s absence.

In 1904, the World’s Fair in St. Louis marked America’s progress in assimilating colonies by holding “living exhibitions” that recreated native villages. The largest of these exhibits was the Philippine village. For seven months, the 47-acre site became home to more than a thousand Filipinos from ten ethnic groups. The Igorots, one of the crowd-drawers from this cruel display, were made to do a dog-eating ritual occasionally done for ceremonial purposes as a regular performance, forever changing the image of indigenous groups in The Philippines. In the online exhibition, Gomez notes of Verzosa: “Working on the project in 2009, Verzosa would ask children in the villages of Kalinga if they wanted tattoos like the ones the women were wearing in his pictures. Back then, they would readily say no. It would be interesting to find out if the answer has changed.”

The weighted memory of the indigenous experience lives not only in the embodied artistic tradition of hand-tapped tattoos but also in the hope that records of the past might protect the present. Pre-pandemic, local and foreign tourists would seek to travel to the village of Buscalan to have their own tattoos by Fang-Od or her grandniece whom she has passed on the skill. It is said that the manwhatok offers designs open for tourists and guests while reserving some designs exclusively to the community—a personal attempt to safeguard the sacredness of the tradition.

I sometimes think exclusivity is forgotten in the world today as an essential filter where information is readily available, and is even sometimes demanded. One might forget that traditions and customs used to be passed down as a right of passage, assuring responsibility, maturity, and discernment from those who would seek their continuity.

In Verzosa’s exhibition, each of the women’s portraits is titled by their names, an effort to encapsulate the personal identity of each of the women, and not solely reduce them as artistic subjects. Visually, the images are all similarly composed as profile portrayals capturing not only the tattoos and the cultural signifiers they wear, but also their moods. Despite all works being similar in form, composition, and desaturation, the images of each person might stand strongly on their own as individuals with their personal biographies, social engagements, and human complexities. Verzosa’s photographic composition of body and face, intentional absence of color and background, and titling the works by the women’s names seem an attempt to strip down the women beyond body—to essence, to recognize them and the notions of their own identity. In this culture, the significance of tattoos is not merely based on their physical appearance, but also on the pain associated with the process of hand-tapping using bamboo stick, thorn, and soot. Of course, each of the tattoo symbols evokes an integral component of their beliefs and customs. Thus, the tradition of tattooing in the community is a heritage embodied not just in skin, but also in memory.

By presenting the portraits, process, and contexts around his project in the online sphere, Verzosa’s exhibition initially aimed to simply document and provide lasting images of a community’s shared tradition and identity endangered by modernity. Acting considerably as mediator, recorder, facilitator, and now circulator, Verzosa’s artistic efforts fundamentally becomes an entry point towards discerning both the individuals’ and the collective’s notions of their past and present hopes.

While the context around The Last Tattooed Women of Kalinga sparks nuanced memories of the colonial past and anxiety of the global present, Verzosa’s portraits and documentation imply a way of exhibition and curation that commends a research-based approach to art-making. Without aiming to represent, only to record, the outcomes are straightforward, capturing body and memory. Verzosa’s conscious exercise around his individual portraits and documentary snapshots might only point towards the unspoken narratives in and around the tattooed women of Kalinga, around which the images hope to immortalize. And that is sometimes enough.

Jake Verzosa’s online exhibition at Silverlens might hint at the complexities ascribed to the nuances of a people of whom he is but a visitor in as the artist efforts to avoid the tendencies of an art form and public exhibition space to commodify and conquer. Verzosa does so with the consideration and discernment one might have for traditions and aspirations shared by a fellow human. His portraits, and documentary images of the women of Kalinga, and their storied tattoos, lives, and relationships with their sacred environment might not readily and directly liberate, but serve a rippling purpose to commemorate a living, breathing memory. •

The Last Tattooed Women of Kalinga is now at Silverlens Galleries’ Viewing Room

John Alexis Balaguer is the manager of operations at Palacio de Memoria arts and events center and is the founder and curator of Curare Art Space. Formerly, he was a curatorial researcher at Ayala Museum, writing for exhibitions and publications, and was managing editor of the museum magazine. His projects include research work for the catalogue raisonne of Spanish-Filipino artist Fernando Zobel and In Focus: Arts and Objects Explained from the Ayala Museum collection. Prior, he was gallery manager at Archivo 1984. Lex received the Loyola Schools Award for the Arts in 2012, and the Ateneo Art Award for Art Criticism in 2019. He currently contributes to Art Asia Pacific magazine and Kanto.com.ph as Art Section grantee.