Words Janelle Año and Judith Torres

Images Lanelle Abueva-Fernando

Crescent Moon Café and Studio Pottery has long been one of Antipolo’s well-loved weekend destinations. Just a quick drive out of Metro Manila and travelers are treated to cool breezes, a relaxing garden view, pottery classes, a sumptuous buffet, and access to the studio’s souvenir shop with one-of-a-kind pieces by the owner and renowned potter Lanelle Abueva-Fernando.

Breaking the mold

It was in Japan where Abueva-Fernando first developed an appreciation for ceramics. After graduating in Fine Arts from the University of the Philippines, her family moved to Japan, where her father (political scientist and public administration scholar Jose V. Abueva), then working for the United Nations, was assigned.

“We started visiting museums, galleries, restaurants—and everyone was using ceramics, all styles of ceramics,” she says. “I decided this [Japan] was where I was going to learn ceramics.” She took a hobby class in Ginza and eventually decided to apprentice full-time under a Japanese master on the island of Hachijo to hone her craft.

For three years, she and five other apprentices would make ceramics under their sensei’s watchful eye. They would take turns making parts of a teapot: one person forming the body, another the spout, another the handle, and so on. In the beginning, the group would make up to five hundred ceramics a day. Their sensei would choose the best hundred and destroy the rest. “It was such a strict way of learning,” she recalls. “All of the designs were by the sensei. We were making hundreds of teacups a day. He would choose the best and destroy the rest. He would choose what he wanted, glaze it, and put his own logo and stamp under the pieces the group would make for him. You work as a team, and it’s all for the master.”

After three years, she needed a break. “The usual apprenticeship is seven years. Anyone who wants to apprentice under a Japanese master—whether it’s kimono-printing, sword or knife-making, furniture, ceramics, calligraphy—the apprenticeship is usually seven years. But then, after three years, I was so antsy! I really wanted to create my own pieces, which was prohibited.”

Freedom to be

“So after three years, I told them I wanted to study somewhere else. And of course, the first comment was, ‘What do you expect? She’s a foreigner!'” She didn’t let it discourage her. She transferred to Sun Valley Center for the Arts and Humanities in Idaho, where they were offering a course on ceramics. Still, she had trouble adjusting. Whereas her former apprenticeship was stifling in its overly regimented approach to learning, she found that she had too much freedom in her new school.

“We were left on our own. We could try the ten different kilns, the thousands of different styles that we wanted. I kind of got lost. I asked my professor, ‘Where do I start?’ And he just goes, ‘Continue what you were doing in Japan, and eventually, it will shape up to something different.'” For the first time, Abueva-Fernando had room to explore and discover a style that was uniquely hers.

“The way I do ceramics is the influence of all the people I’ve met,” she explains. “I was exposed to different cultures. I was taught in Japan and the US. People in Japan say I have Western influence. People in the West would say I have Japanese influence—so I guess I’m in between,” she says. “Being Filipino, that’s where everything is merged. That’s how I come up with my own look.”

Abueva-Fernando’s art is an exciting confluence of factors and influences, leading to a style that is eclectic, rustic, and refined all at once. She credits her teachers, travels, and family (her uncle is National Artist for Sculpture Napoleon Abueva) for her diverse influences. When Mt. Pinatubo erupted in 1991, she started incorporating local volcanic ash into her pieces—a technique she picked up from her apprenticeship in Hachijo, itself a volcanic island.

When she came home to the Philippines, she put up her own studio in 1981 before moving in 1991 to Sapang Buho (Bamboo Stream) in Antipolo City, where Crescent Moon Café and Studio Pottery now stands.

A family legacy

A visit to Crescent Moon isn’t complete without trying their lunch buffet, beloved for its Southeast Asian fare and hearty Filipino dishes. The menu was developed by Abueva-Fernando’s late husband, Bey Fernando. The couple started the café after Bey closed his litigation practice for health reasons. His second-best love was cooking, so the next natural step was to open a café offering his favorite dishes. “It was a partnership,” Abueva-Fernando says. “I would make the plates, and he would cook the food.” The first dishes the café served were signature dishes he personally served to family friends and recipes from cookbooks that he adapted and fine-tuned to perfection.

When Bey passed away two years after opening Crescent Moon Café, Abueva-Fernando considered closing up shop. “Until one day, I came home to my children with all these cookbooks in their room. I said, ‘Oh, do you have cooking for homework?’ And they said—they were only nine and ten when he passed away—they said, ‘No, Mama, we heard you want to close the café, so we’re studying how to cook, so you won’t close the café!'” And so Crescent Moon remained open.

Even the café’s name, she fondly recalls, came from the kids. When they were young, the children had a make-believe restaurant that the couple would order from. When the kids were asked what their restaurant’s name was, serendipity stepped in: “So my daughter looks up at the ceiling. She was five years old at the time. The first thing she sees is a quilted pajama with a crescent moon. She goes, ‘It’s the Crescent Moon Café!'”

Her children, now in their thirties, have since migrated to Hong Kong and the US, but they still help out with the café’s social media, while Bey’s recipes live on as part of the café’s line-up of dishes on rotation.

Perfect imperfect

Today, Abueva-Fernando supplies coffee shops, restaurants, franchises, hotels, and other establishments with ceramic tableware. But she remembers a time when orders were hard to come by. From 1981 to 1991, she juggled her exhibits with trying to sell her ceramics to skeptical restaurants. “The restaurants would tell me, ‘Ay nako, tabingi ang ginagawa mo. Ay nako, inconsistent ang glazing. Ay, nako…’ (Oh no, your work isn’t straight. Oh my, the glazing is inconsistent. Oh no…) So many complaints.

“But then in 1991, I got a break,” she recounts. “There was a restaurant that wanted a one-of-a-kind look. So I made ceramics for them, and then Mandarin Hotel saw it, Manila Peninsula followed, and then all of the hotels started coming to me. No more commercial looks for their outlets.”

Most of her work now is custom orders. Daughter Majalya Fernando, who worked the café and studio with her mom before migrating to the States, explains how it goes: “Clients approach her with a certain shape or color they want. The clients with very specific requests are usually chefs. They know exactly how they want the pieces to look with the food they prepare. A few clients will give her a color scheme to work with, and she’ll do a few samples for them to choose from. A lot of times, it’s the clients dictating what they want. As long as they are okay with the pieces not having a uniform look, and it is something her studio can do, she will take the order.”

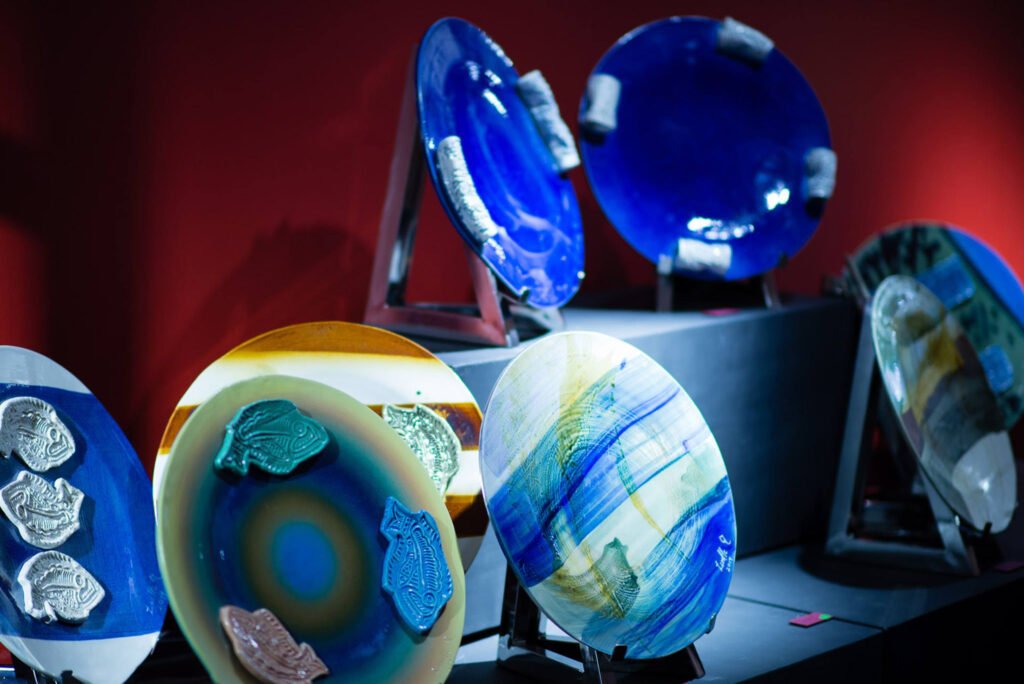

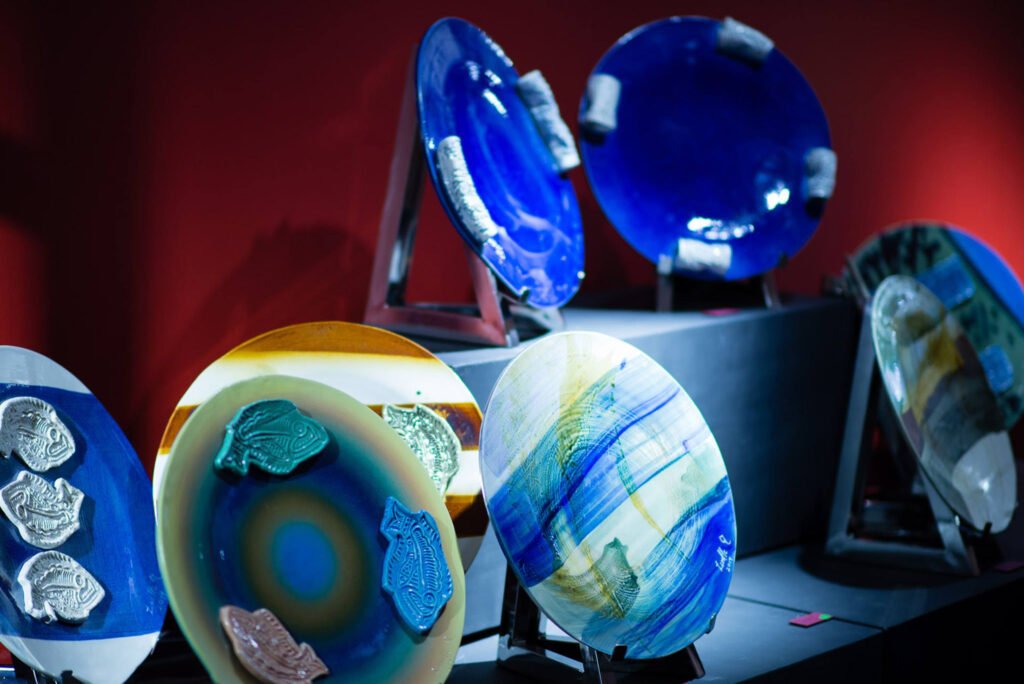

Every few months, when she has the time, Abueva-Fernando will make pieces for herself. She will either make a completely new shape or take an item like a large platter or slab and treat it as a canvas, coloring the way she wants. When they’re done, those pieces go to the store shelf at Crescent Moon Café.

The pieces Abueva-Fernando does for herself are the result of spontaneous artistic expression. That’s not to say she doesn’t plan. The thing is, the only person who ever knows the plan is she.

Fernando explains: “She draws designs but only to show dimensions, not really any detail. There was a time I helped her with forms for submission to a ceramics show. I asked her what she was going to make because I needed to write a short description. She said, ‘Basta, I know na. I know what I’m going to make. I’ll work on it in the studio tomorrow.’ I asked her to draw it, to give me an idea. The funny thing about my mom, she cannot draw. If you ask her, she will say the same thing—that she chose to work with clay because she can’t draw! She really thinks in clay and color.”

Strict in the studio

Abueva-Fernando is a master of her craft, but she hasn’t taken apprentices as her sensei in Hachijo did. Her daughter says, though, that her mother is a strict master in the studio.

“I see a lot of the dedication and discipline she picked up in Japan in the way she runs the studio. She has over 20 employees who make molds, pour clay, glaze, and fire pieces. She is strict with how they spend their work hours.

“At the same time, she is also very motherly. When the COVID-19 lockdown happened, and several home cooks started their own food businesses, she would order merienda (afternoon snack) several times a week from different businesses. She told me that she knows what it’s like to do manual labor in the studio for several hours a day, that it’s hard work. The merienda is her way of giving the employees a break and showing her appreciation.”

Born of clay

She may be strict in the studio, but clients and her daughter will attest that Abueva-Fernando is playful when she teaches workshops. “She tells students to relax and not work the clay too hard; that if you are too tense, your piece will collapse (and it does, especially if you are tense at the wheel!). She reminds students to have fun. I see this playful side reflected in the ceramics she makes for shows and exhibits. The pieces she creates for shows are not for any custom order. She doesn’t have to work the pieces too hard; there is no client to please. She can have fun.

“When I was living with her and working in Crescent Moon, I had a personal rule that we could not talk about work at home after a certain time. One day, she started talking about ceramics at 10 in the evening. I called her out, and she said, ‘But it’s not just work. Ceramics is my life!’ She really loves what she does for a living.”

Looking to the future

With the rise of hobbyist potters and pottery studios popping up everywhere, where does Abueva-Fernando see the future of ceramics in the country? “I’m very happy that there are now so many workshops and schools that everyone’s doing so well. In fact, everyone picked up during the pandemic because everyone wants to go back to basics.”

“It was a dying art here before. In the provinces of Ilocos, Iloilo, Pampanga, they still make terracotta pots. It seemed like it was stagnant, but in came the studio potters, now everyone’s making it. And the public is learning to appreciate it,” she says proudly. The buyers, too, have matured, preferring to patronize all things local. “China was killing us [Filipino potters] for the past fifteen years. There are too many factories in China where they have a machine, you just put tons of clay in it, and it can make thousands a day while potters can only make tens, hundreds of pieces.”

However, she’s confident that even with mass-produced ceramics, there will always be a clamor for the handmade, the special, the one-of-a-kind. “Oh, it’s different. When it’s handmade, the look is different, the feel, the shape, and color, the glazes… you can definitely tell.” •

Janelle Año is a retail marketer by day and a dilettante by night. When her nose isn’t stuck in a book, you can find her attempting to contort herself into pretzel-like positions, picking open locks, divining with tarot cards, taping her Survivor audition video, and just dabbling in her many hobbies. Follow her on @strangeways_tarot.

Crescent Moon Café and Pottery Studio is located at Sapang Buho Rd. Brgy. Dalig, Antipolo City. Open from Wednesday-Sunday, 9 AM – 5 PM. Guests are requested to make reservations at (02) 8234-5724 or through Facebook. À la carte options and al fresco dining are available; however, lunch buffet and pottery classes are temporarily unavailable due to COVID-19 health protocols.