Words John Alexis B. Balaguer

Images Jo Tanierla and UP Vargas Museum

Hi Jo! Congratulations on bagging the Ateneo Art Awards this year.

Your show at the Vargas Museum, Pagburo at Pag-alsa: Natural Depictions and Illustrated Prophecies (Galacio, 1910) in October 2020 brought together accounts and illustrations that touch upon historical narratives, mythology, magic realism, and political anxiety in a most unique way. How did the idea and execution for this exhibition come about?

Thank you, John!

Pagburo at Pag-alsa is largely an expansion of the methods in Mga Maiikling Kuwento ni Onat sa 10th World Scout Jamboree, which was part of the 2018 group exhibition Project Island Hopping – Reversing Imperialism: Lander at the Vargas Museum. It was my first attempt at consolidating fictive stories, myth, invented lore, and fabricated research into a contained body. Pagburo and Pag-alsa is a more careful and rigorous approach. I first encountered fabrication from Cian Dayrit’s Bla-bla Archaeological Complex (2013). It planted the idea of presenting fiction as an academic exposition, which I would revisit in 2018.

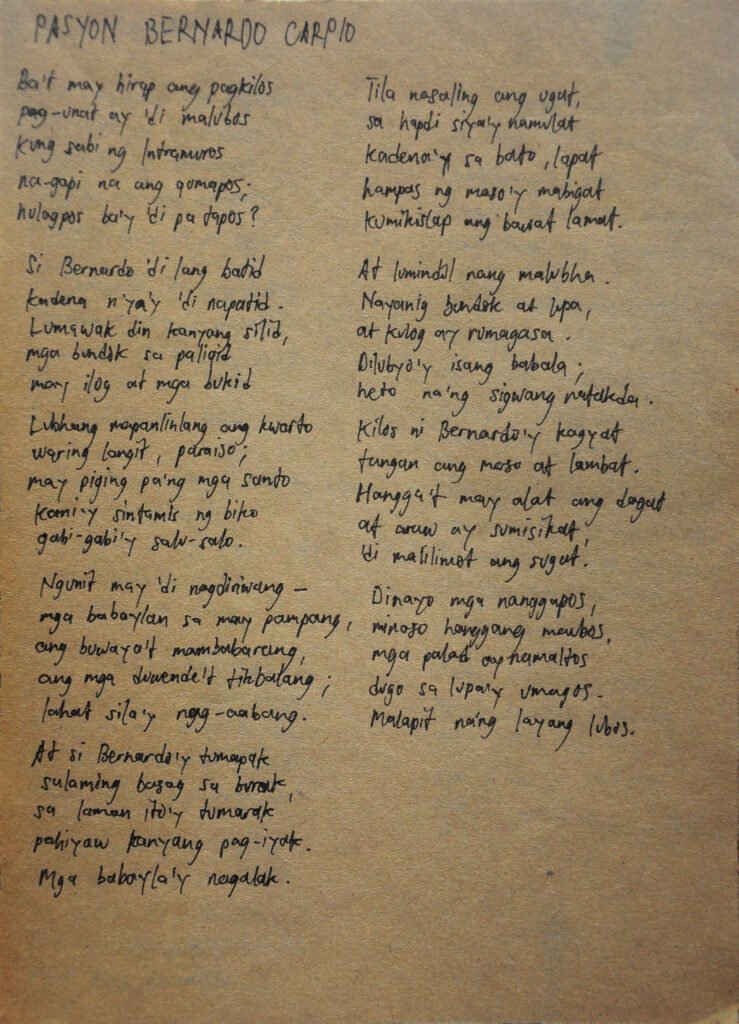

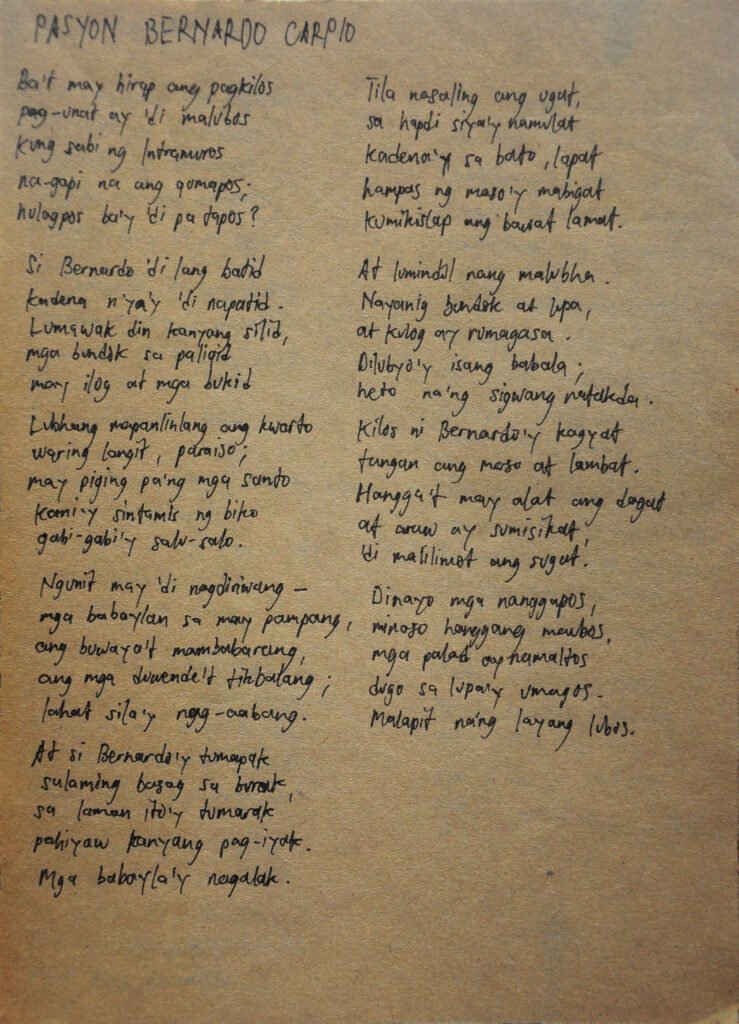

As for the formation of Pagburo at Pag-alsa’s setting, Reynaldo Ileto’s book, Pasyon and Revolution (1986) is a crucial reference. Various historical coordinates are from this dissertation, including the agimat and pasyon pieces. Babae, Obrera, Unyonista (2011) by Judy M. Taguiwalo informed Pagburo at Pag-alsa’s urban context, especially through the labor movement’s anti-colonial orientation. And Body Parts of Empire (2016) by Nerissa Balce provided me with an ideological framework of imperialism’s actors, their motivations, alibi, their dehumanization of their intended targets. I played around with these ideas—civility, benevolent assimilation, the white Adamic, etc.—subverting or mocking them throughout the project.

The local geography referenced in your works such as mountains, forests and seas are ascribed with supernatural stories and possibilities. Have you always been interested in local lore?

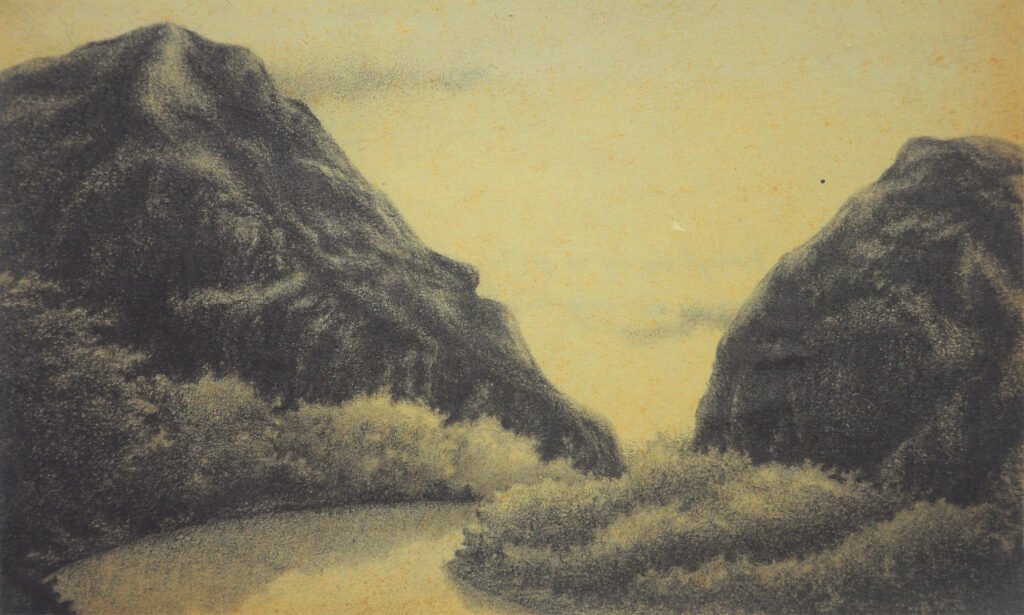

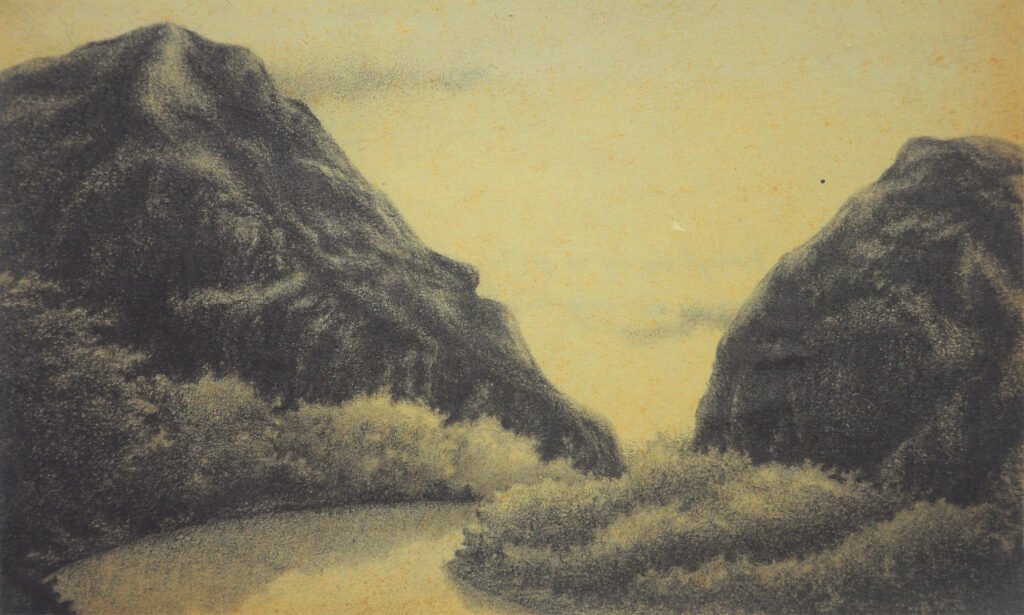

In many ways, the supernatural is a way of grappling with our archipelago’s topological features. Growing up in a semi-urban neighborhood, flanked by forests and a farm, folklore was an integral part of my childhood. This was further reinforced during one particular visit to my grandparents in Montalban, when I first heard of Bernardo Carpio. What moved me so was their assurance of this lore’s physical evidence, and thus its vulnerability to investigation. They claim that impressions of Bernardo’s massive feet are at the bottom of Marikina River, in the segment between Pamitinan and Binacayan. The giant Bernardo apparently had once prevented the arguing mountains from collapsing into each other by standing between them, keeping the mountains apart through sheer strength. I was in awe with Bernardo and his exploits, and with the sentient mountains moving well beyond their geologic parameters, and with the possibilities embedded within folk narratives.

But I eventually lost that affection, until I saw artist Sir Bob Feleo’s works. They resurfaced my interest in Philippine mythology, and it has been a sporadic, though ample, adjunct to my works ever since. The Soul Book (1991), a collectively-authored text on pagan religion and practices was a major reference. His Tau-tao works were also crucial in my years as an art student.

Your works surface a deep appreciation to literature as much as the visual arts, referencing your own research on poetry, classic Filipino novels, as well as mythology. What sort of books and publications can we find in your reading list?

Most books and papers are on imperialism, and the American period (read: 1898-present) of Philippine colonial history. There are several titles too on the different aspects of Philippine culture—language, illness, and remedy, art criticism, various curiosities, etc.—with an anti-colonial orientation. I also have poetry chapbooks by contemporary Filipino writers, and an uncategorized assortment of fiction. There are also zines from my BLTX excursions and some from dear friends. The ones by Magpies are among my favorites for their humorous satire on reactionary institutions. There are also books on Western art, which I bought mostly for the pictures, and to get a working knowledge of its history.

I also have a Michael Jordan biography, with lots of pictures.

I had a chance to browse through some of your early works. Can you tell us more about your 2015-2016 series of works referencing Modesto de Castro’s 19th-century literary piece Urbana at Felisa?

The Urbana at Felisa works criticize the outdated, yet persistent politics of de Castro’s text. Clergyman Modesto de Castro inflicted Catholicism’s feudal mandates, in a Spanish colonial setting, through the epistolary novel. I tried subverting those conservative and oppressive values by orchestrating scenarios that convey the sisters’ agencies, or a semblance of it. I also manipulated the paintings’ linear perspective, projecting the vanishing points of certain elements according to the characters’ viewpoint instead. It was an attempt to create a ‘reality’ informed by the characters’ perspectives; the world according to Urbana and Felisa.

How did you aim to harmonize the idea of employing magic realism and figuration in a number of your works? Can you cite for us a personally favored work that employs this?

I think they already are a perfect match, and all I really did was to further explore their consonance. With Pagburo at Pag-alsa, the naturalistic figurations help create an ordinary environment where the subtle fantastic would thrive. Harmonizing in this context is also disappointing the expected behavior of physical reality.

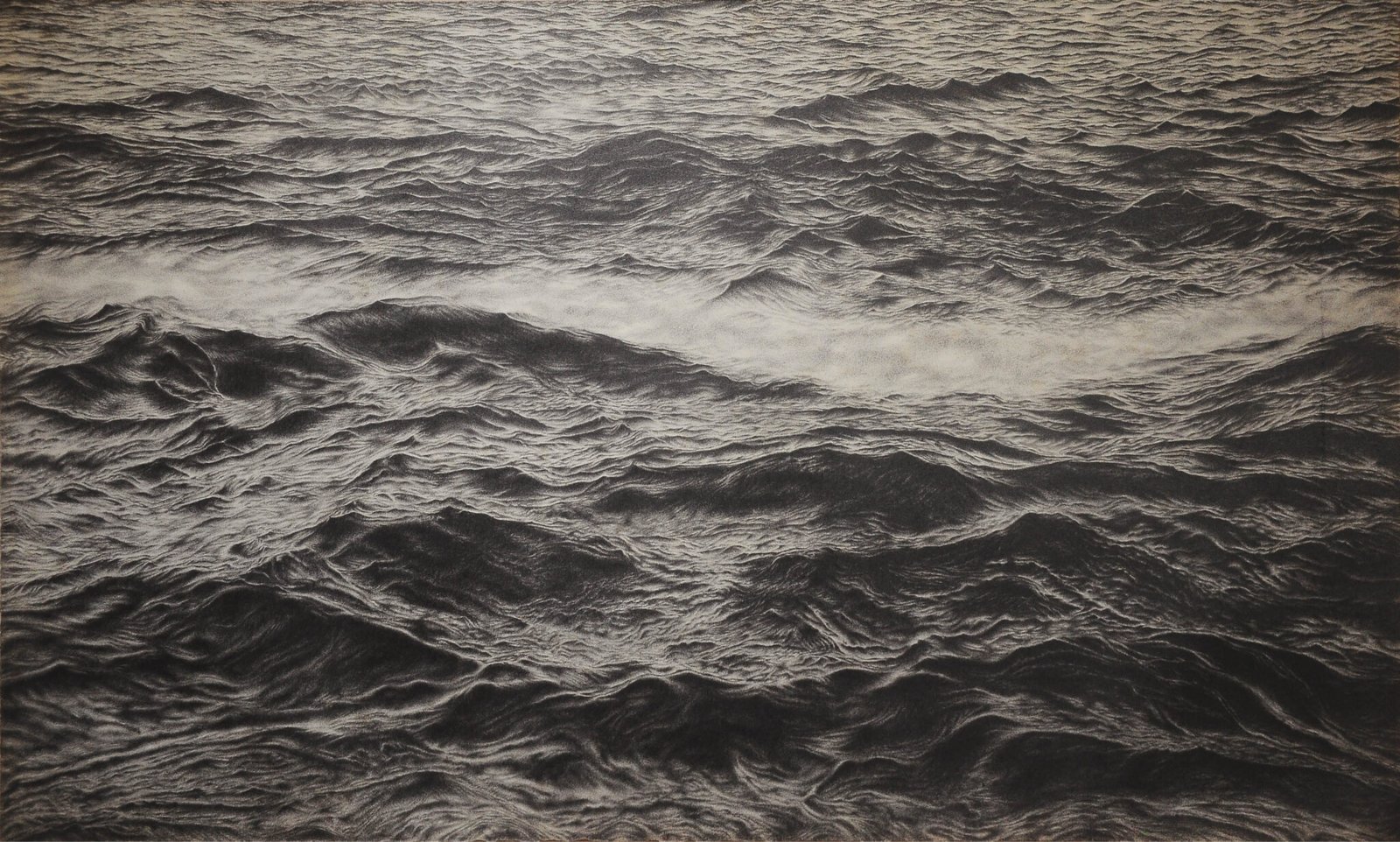

And on this consideration, the work doon kung saan halos patag ang tubig at tumitigil ang mga alon, doon mababasag ang tanikala (2019, header image) is my favorite. Also, halos apat na buwan ko siyang ginawa! (I spent almost four months making it!)

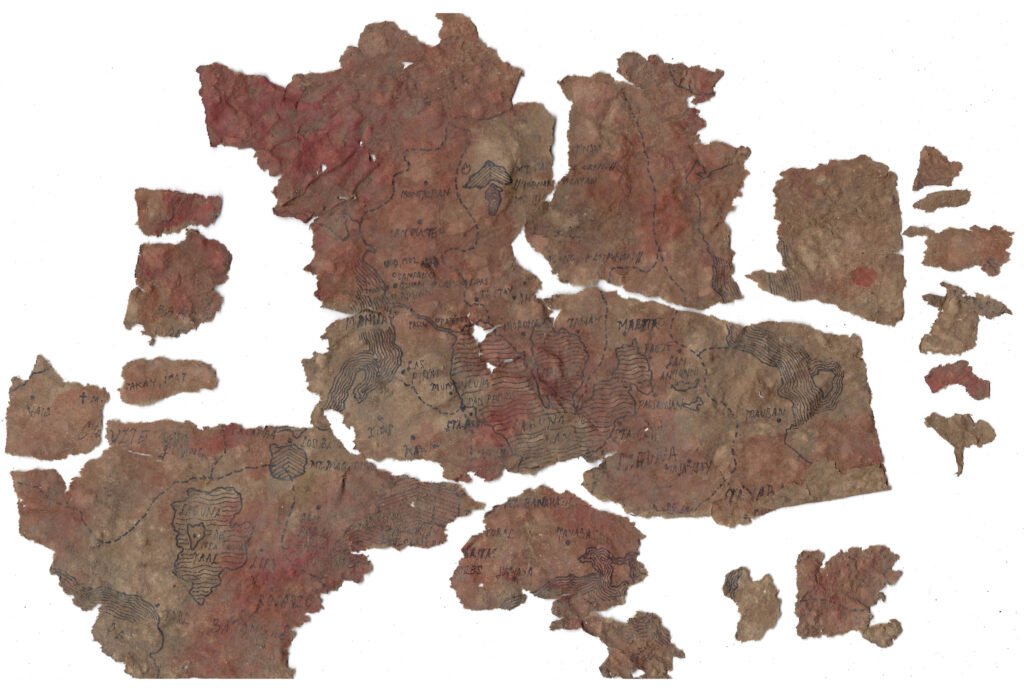

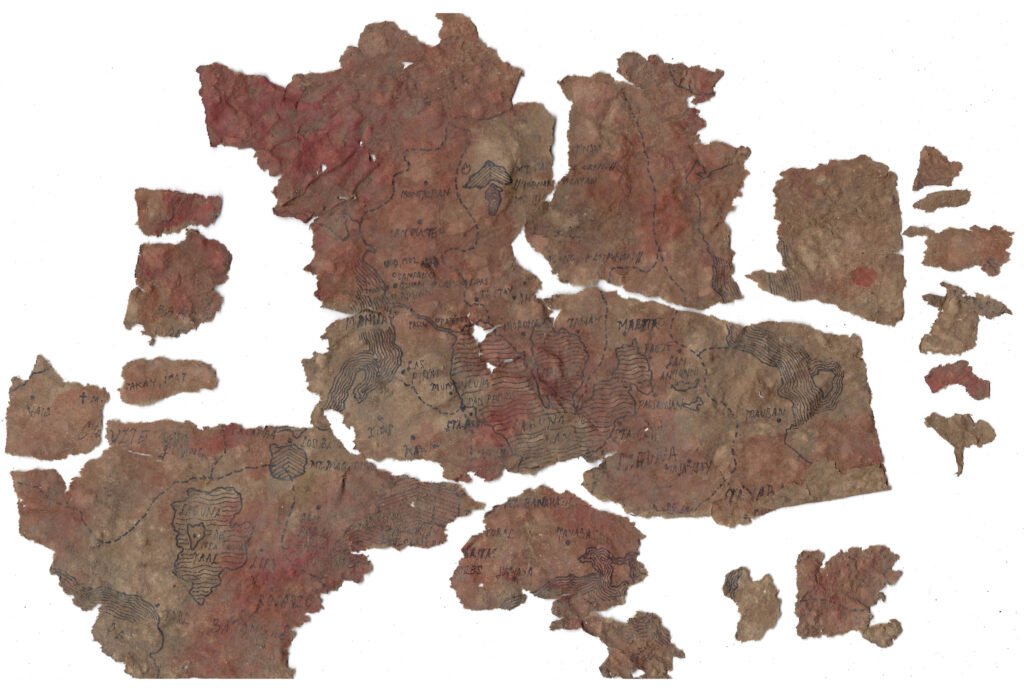

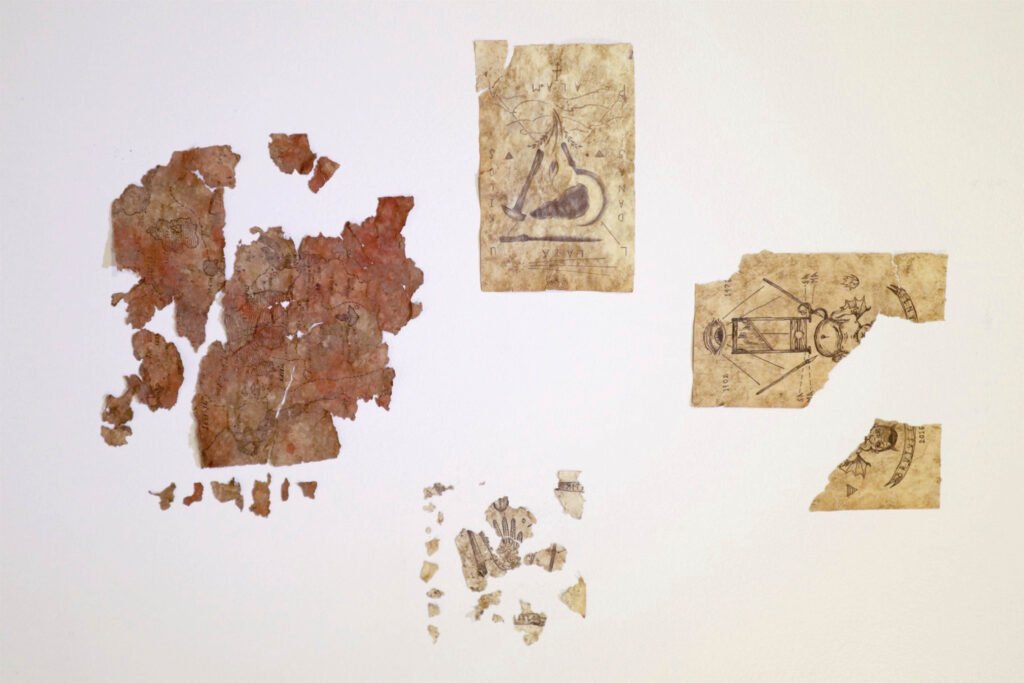

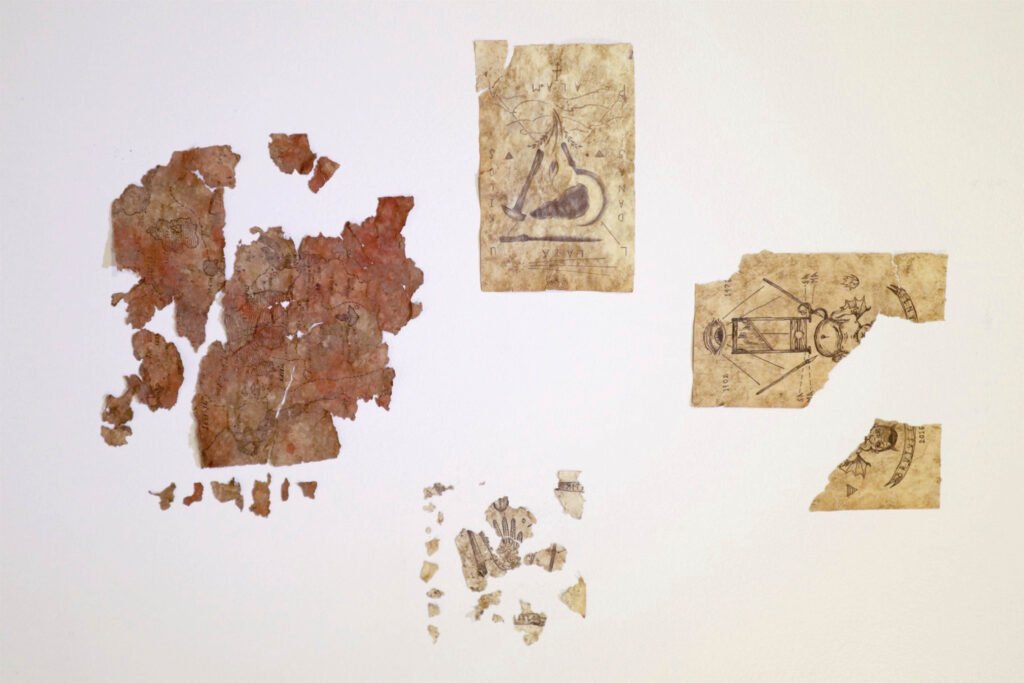

You mentioned in your exhibition walkthrough for Pagburo at Pag-alsa that Altar ng Sakuna at Dusa (2020) was buried in soil to achieve an appearance of age. Were there other unique considerations that were brought into light as you developed in general your production process as an artist?

Altar ng Sakuna at Dusa (2020) was intended to be a neat graphite illustration: Duterte’s bust, surrounded by signifiers of his fascistic and inept governance, placed on a skewed, bloodstained drawer. The curator Carlo Paulo Pacolor had pointed out that the finished work was too “attractive” for its subject, and proposed that we disrupt this quality. After recognizing the sterile illustration’s inadequacy, I suggested that the work be buried, and be re-presented with the soil it was buried on. The result added another layer to the tattered drawing, a prophetic ‘proof’ that invades the material: Duterte’s regime shall be buried, its decayed constitution a fertile loam for the creation of a better ecosystem.

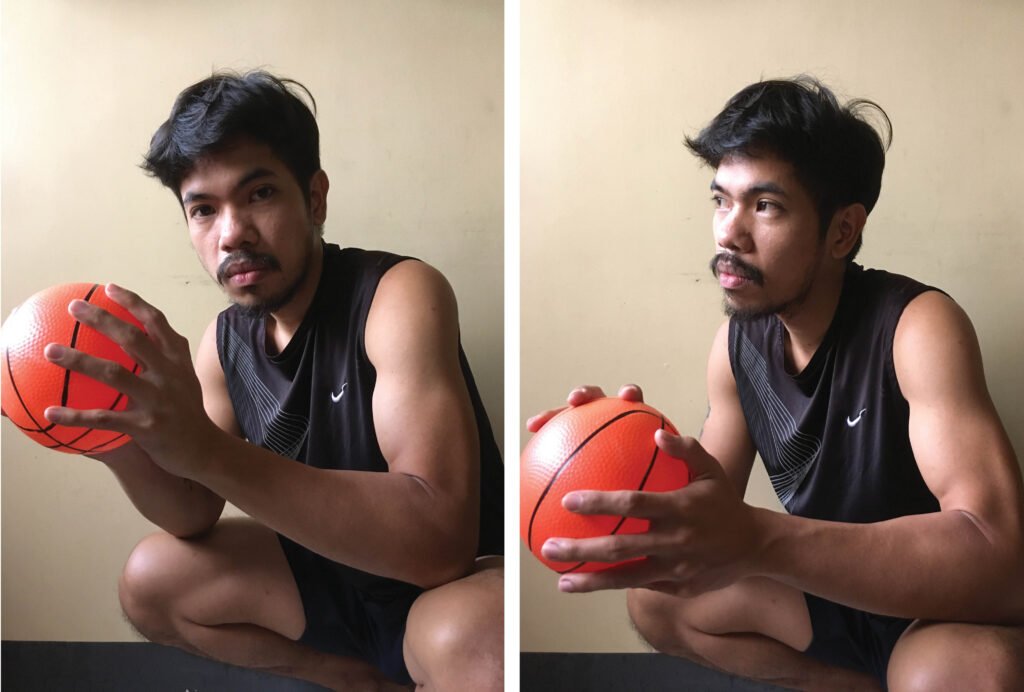

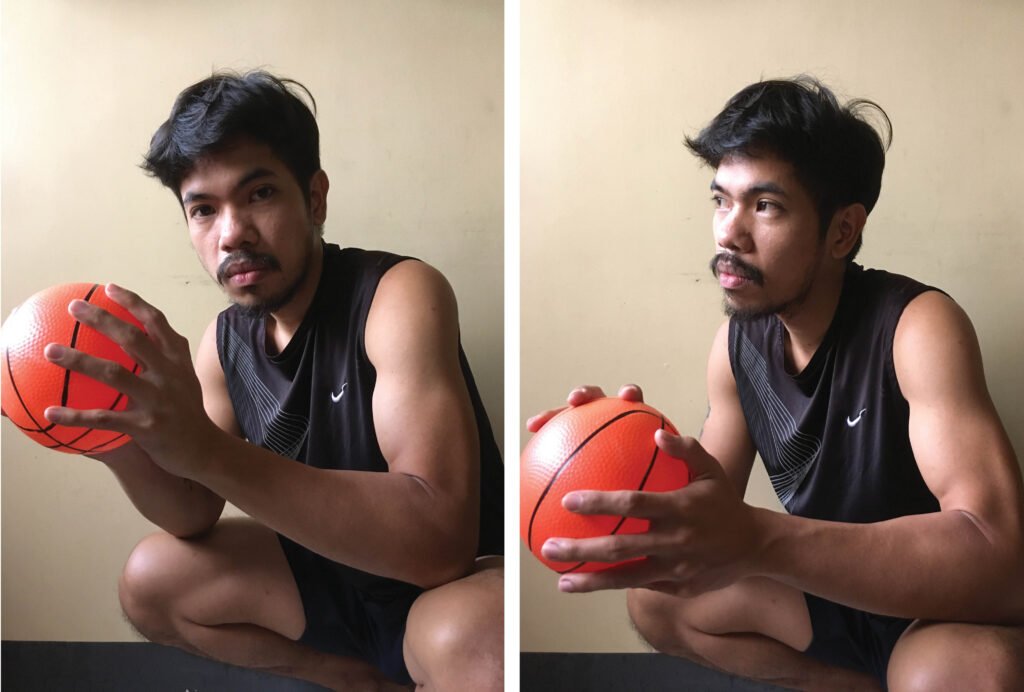

Another favorite configuration, and something I haven’t explored with Pagburo at Pag-alsa, is the presentation of the amulet notations Pag-aagimat ng mga tagapatag (2020) as actual objects. A work from the series, the one depicting a human liver, was supposed to be painted on a piece of cloth to function as an armor of sorts. This cloth was to be worn around the torso, with the liver illustration secured on the segment where the actual liver is. I suppose thinking of Pagburo at Pag-alsa in such malleable terms complements the rigidity of my drawing technique, keeping the production process from becoming too rigid and mechanical.

A number in your series of works seem to exhibit resistance to colonial, capitalist, and imperialist forces. How do you immerse yourself in exploring and responding to these often-weighted realities?

Imperialism, according to Lenin, is the highest stage of capitalism. To be precise, imperialism is the logical follow-up to monopoly capitalism; a powerful nation’s diplomatic and/or militaristic invasion of economically weaker countries. These colonized countries become sources of cheap raw materials and cheap labor power. They become a market as well, forced via neoliberal policies to consume the surplus products the invading nation manufactures.

Pagburo at Pag-alsa argues for a resistance to this predatory system. Imperialism, as an organized effort inflicted by the few, necessitates an organized resistance too, by the entire oppressed population. A productive response is a series of communal gestures: learning, living, resisting, and mobilizing together. In joining a progressive organization, I was able to attend to these tasks, and doing so has guided my practice into appropriate directions.

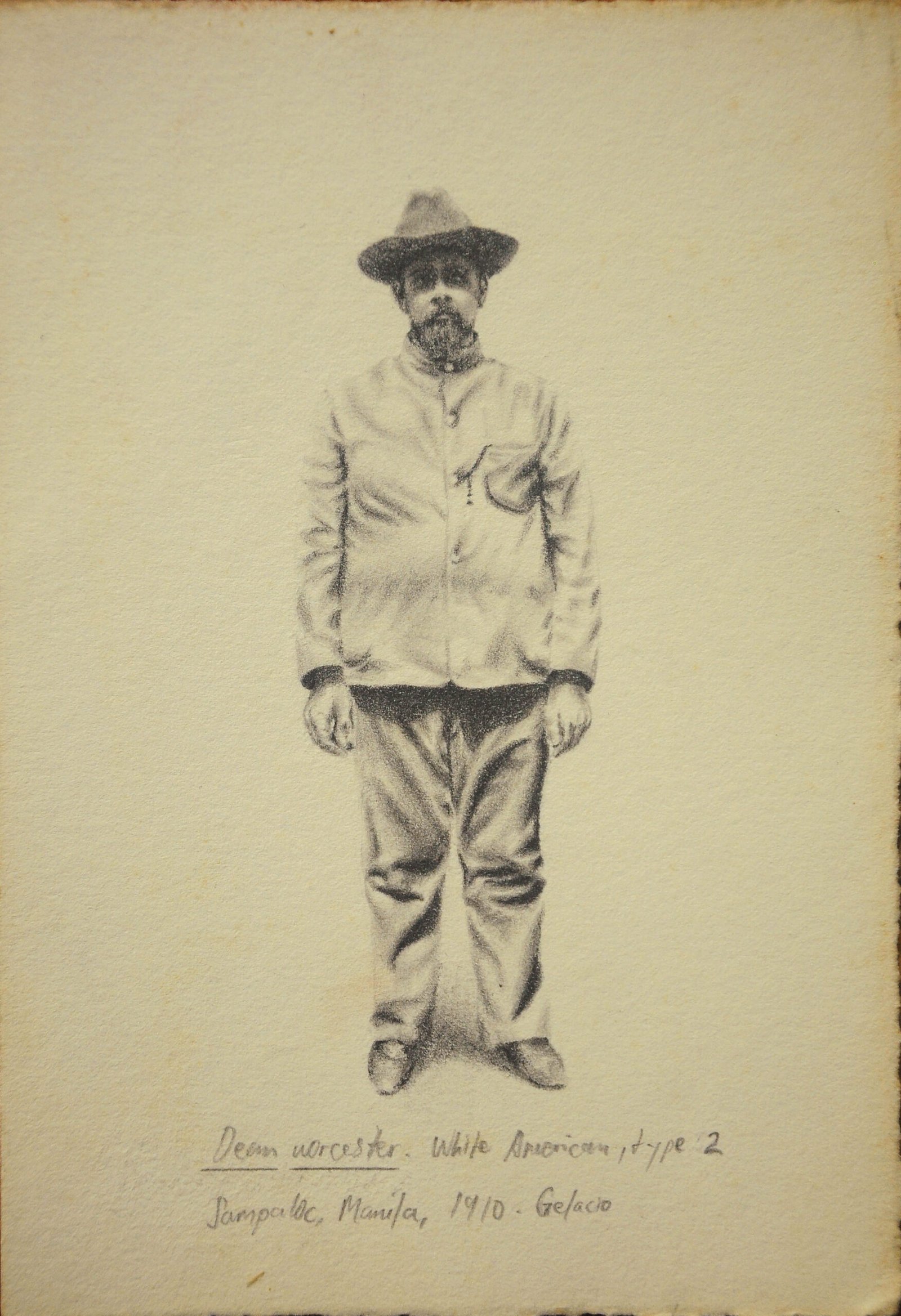

Left: Dean Worcester, 2020, graphite, paper, 18.5 x 12.9cm, Right: kamay na bakal, 2020, graphite, corrugated metal sheet, 85 x 62cm

The site-specific Kamay na bakal (2020) installed amongst the natural elements outside the museum hints at extending one’s efforts of service to the ground level where socio-political issues may be directly addressed. Can you share with us some of your advocacies and efforts outside the art gallery?

On a more tangible level, imperialism also wields diplomacy, often through national policies on economy, foreign trade, education, and other social arenas. The consolidation of massive parcels of agricultural land by a few landlords; absence of heavy manufacturing industries in the country; neoliberal trade policies; the persistence of contractualization and the absence of a national minimum wage law for workers; the harassment of workers’ unions; the impending jeepney phaseout; the K-12 program and tuition fee hikes; the volatile oil prices; and other mandates that exploit our society’s basic and middle sectors in favor of big businessmen, compradors, and big landlords are imperialist manifestations too. And so, the idea is to work together in resisting these oppressive dictates.

In Tambisan sa Sining, a cultural mass organization, we constantly learn about the relationships of such seemingly segregated struggles. We try to discern how one affects the other, or which ones are the most pressing given a specific context. The gathered knowledge is then practiced to determine its efficacy or its validity. And this process of knowing, informed by communal caring, guides the appropriate course of democratic action. Therefore, it is inevitable too that our community initiatives like soup kitchens and pantries; art and writing workshops; and even the production of murals, banners, effigies, and other mobilization collateral are functions of resistive orientations and mutual endearment.

It is refreshing to see works today that implement traditional media within contemporary art spaces. Can you run us through your drawing and illustration production? What references and materials do you usually gravitate to and why?

That’s an interesting observation, and thank you!

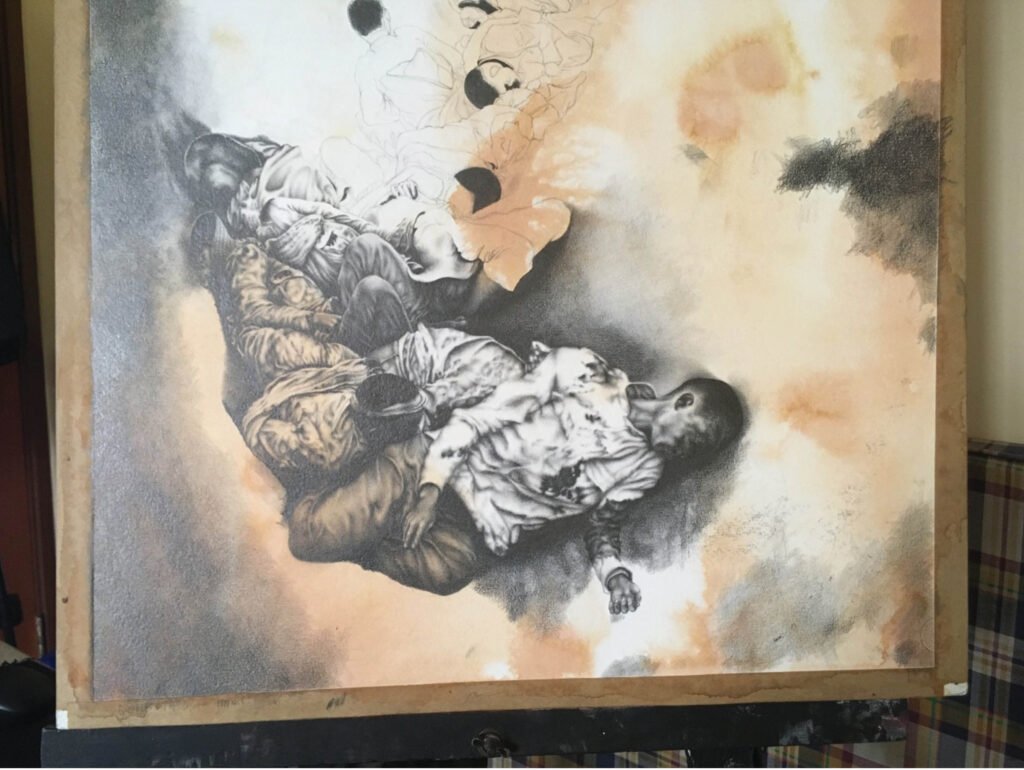

A drawing I’m currently working on is after a detail from Milagros Guerrero’s essay The Colorum Uprisings: 1924-1931. It reads, “The Constabulary allowed the corpses of the Colorums to rot on the spot where they fell, the better to prove to all and sundry that the Colorums did not have supernatural powers to resuscitate themselves.”

I think this move by the Philippine Constabulary was somehow counterproductive, that in desecrating the bodies they somehow reinforced the Colorums’ claims of invulnerability. I like to think that it also betrayed the Constabulary’s anxieties in going against fellow Filipinos who took the revolutionary path of resisting American colonization. And on my drawing—Filipino casualties of the Philippine-American war lined up in a rudimentary trench—I plan to confirm the fears of the oppressor; the death of the flesh cannot impede the revolutionary struggle. So, my works often start as such: a response to historical texts. Realism is my go-to approach, but I often disrupt it with subtle violations of physical laws and their properties.

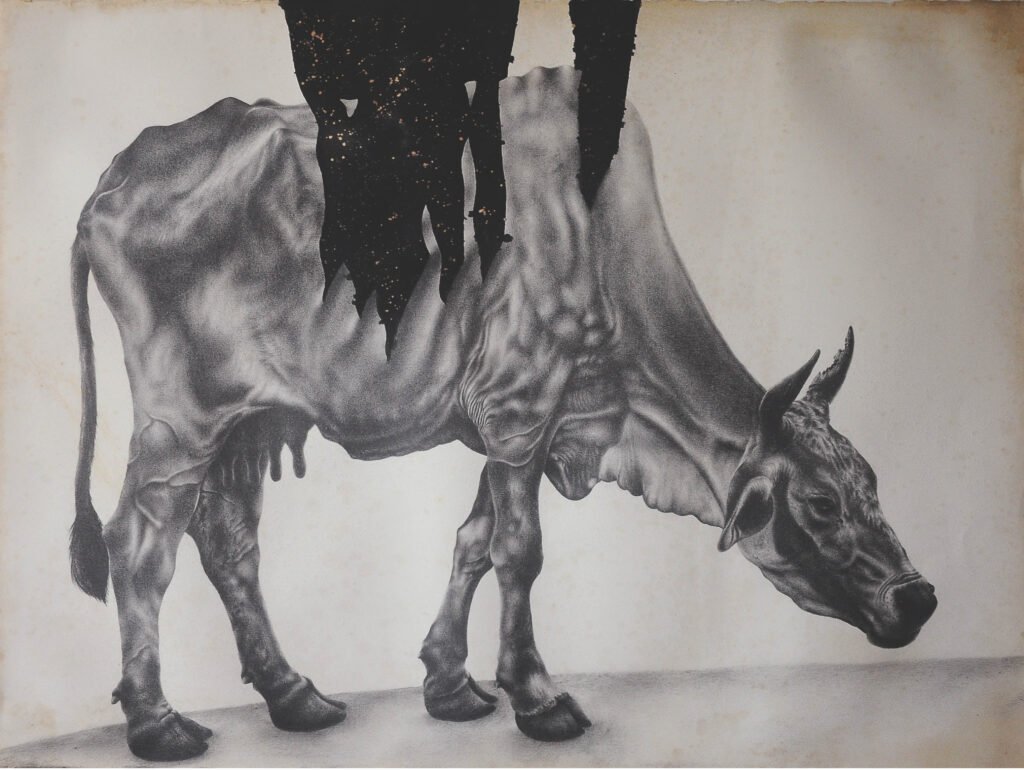

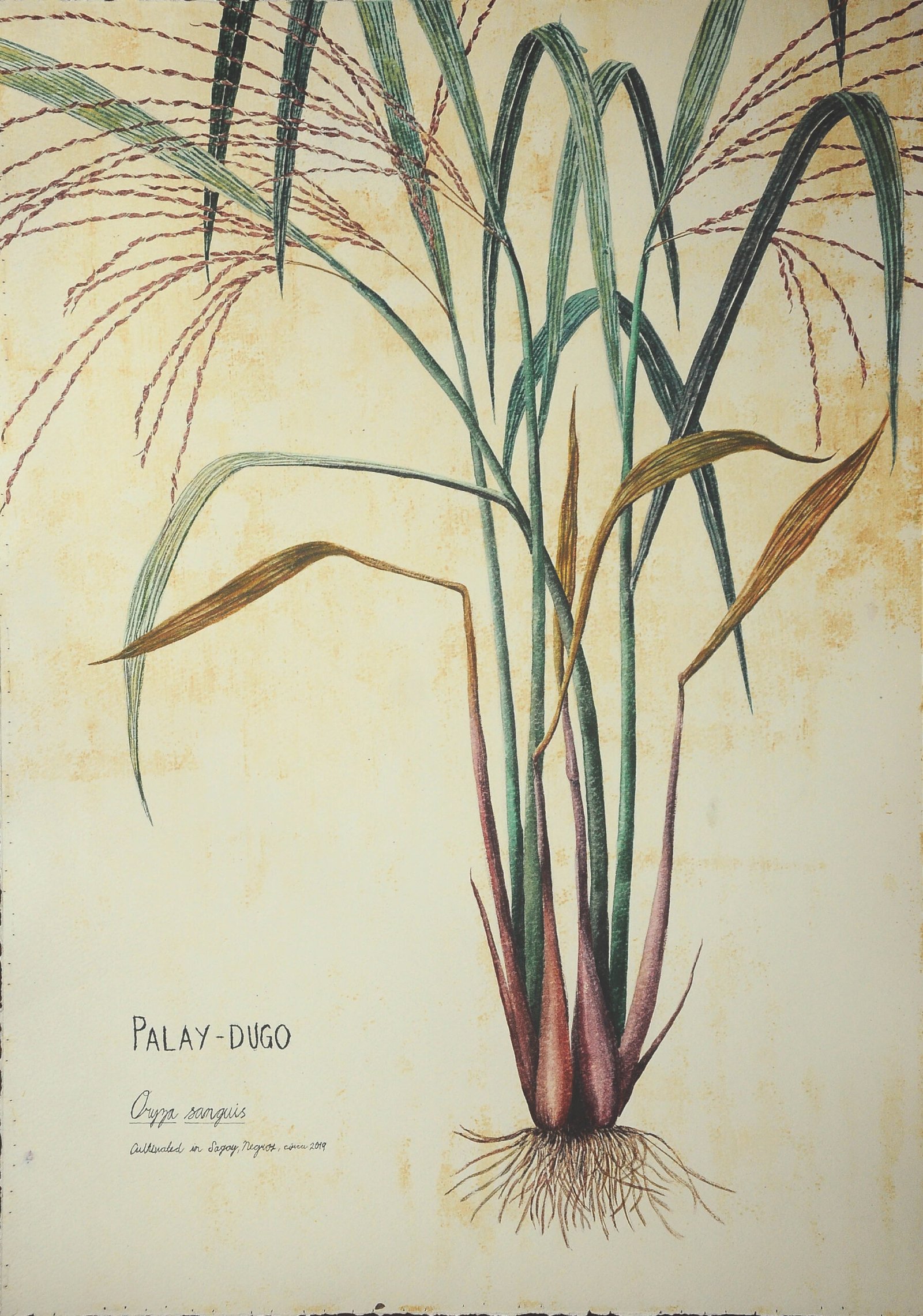

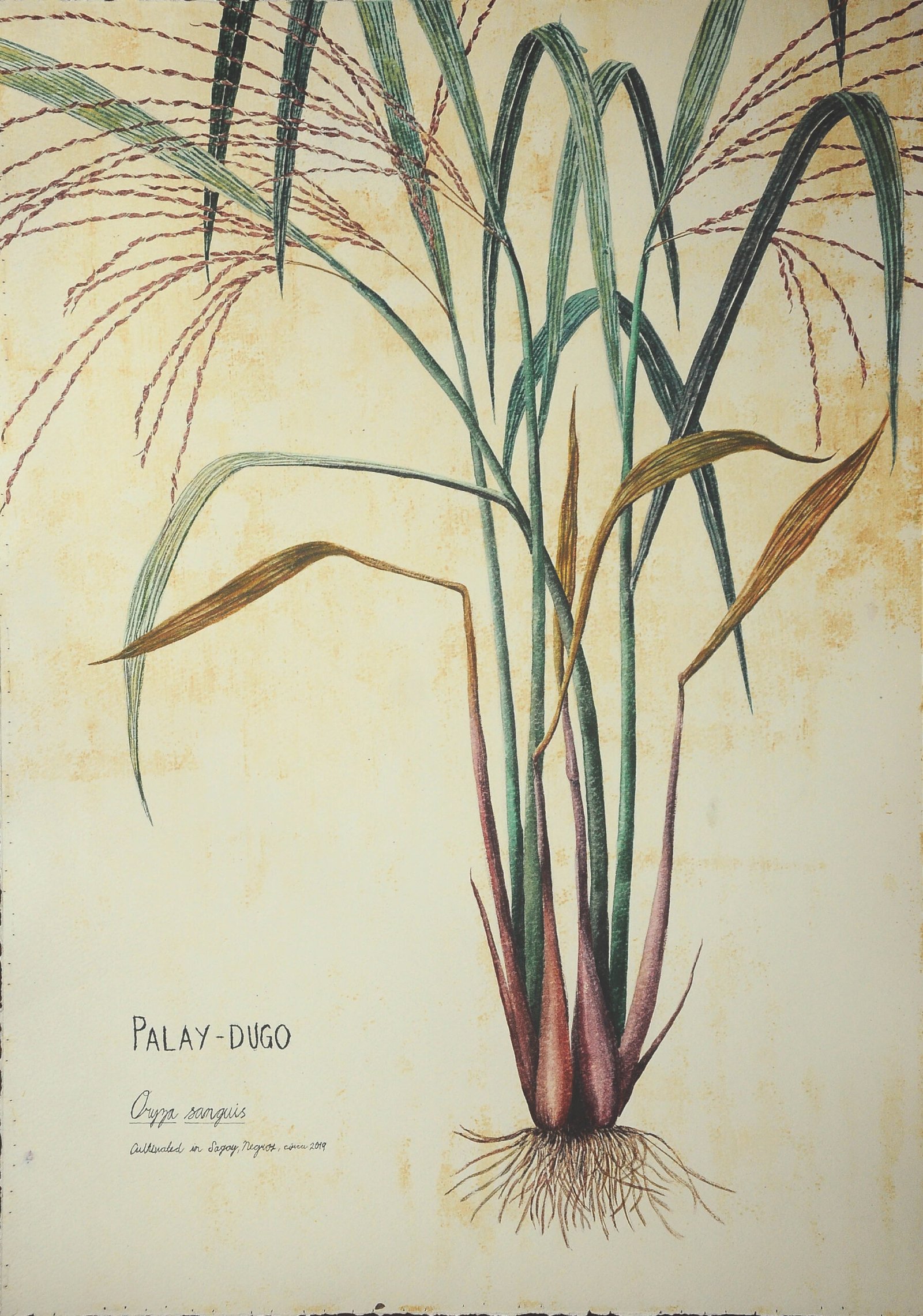

I also very much enjoy using graphite pencils. It allows for intricate rendering, for depicting soft light. And because of the surface quality I want for my works, using graphite necessitates a tedious, patient process. I also insist on working mostly with an achromatic palette. If the work demands color, like Palay-dugo (2020), I try to maintain a subdued color scheme, not too saturated, and not so liberal with different hues. I think in limiting a drawing’s visual information, the viewers are forced to supply their own ideas, to verify their impressions, thus facilitating a more rigorous engagement. But I may be wrong [laughs].

As a visual artist who is inspired by local memory—largely informed by social history—while conscious of the experiences in the grassroots, what do you hope the community takes from experiencing your art?

Our severe, century-old political situation, compounded by colonial history, has always warranted an urgency of taking up the struggle of the basic sectors: small farmers, farmworkers, indigenous peoples, wage earners, the informal workers, the urban poor. A sincere participation would make one understand that a just, free, and humane society is only possible when those who participate in production are liberated from systemic oppression. We must actively and collectively resist the systems of power that manufacture oppression. And an art-making that serves the people can be one starting point. •

John Alexis Balaguer is an independent art manager, critic, and curator based in Manila. He is the founder of Curare Art Space, a digital space for curatorial collaboration. He was formerly operations manager and head of research at Palacio de Memoria, a heritage house turned arts and events center; curatorial writer and researcher at Ayala Museum, writing for exhibitions and publications, and acting as managing editor for the museum magazine; and gallery manager at Archivo 1984 gallery. Lex received the Loyola Schools Award for the Arts in 2012, and the Purita Kalaw Ledesma Award for Art Criticism in 2019. He currently contributes to Art Asia Pacific magazine, and Kanto.com.ph. On better days, Lex makes digital art and writes poetry.