Words John Alexis B. Balaguer

Images UP Vargas Museum

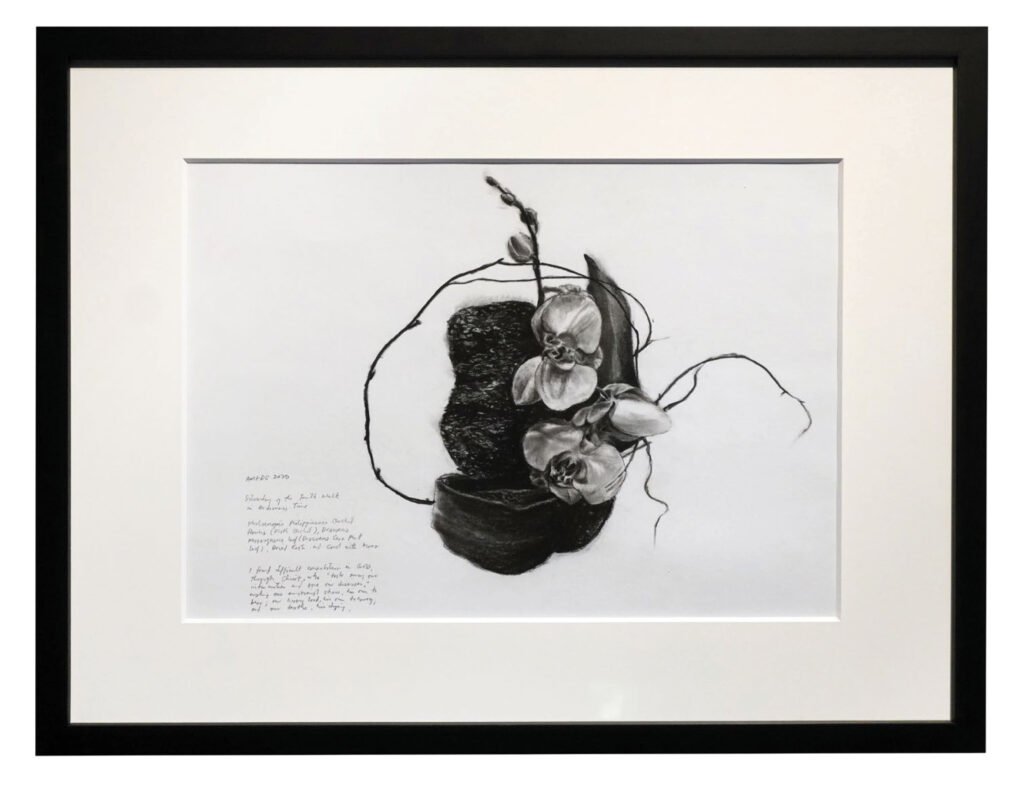

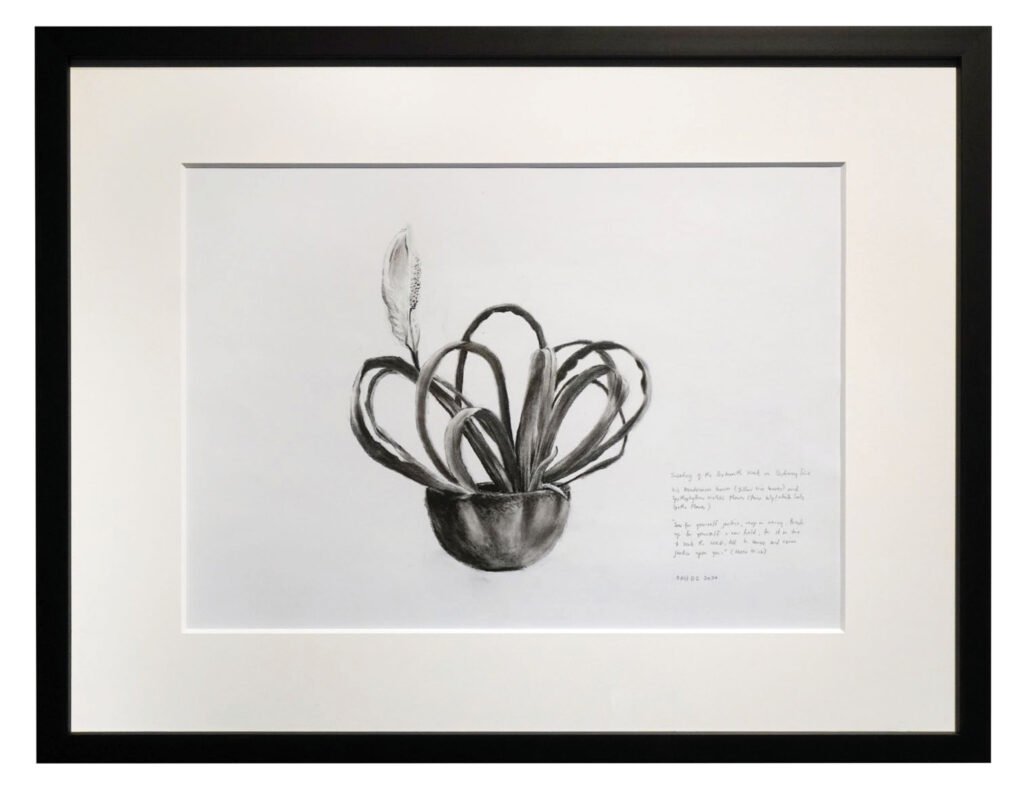

When Threatened, They Bloom Series, 11.75 x 16.5 in/29.85 x 41.91 cm, Charcoal on paper, 2020

Header: Herbarium, Dimensions variable, Dried flora specimens pinned on a green wall, 2021

I first encountered the work of Filipino contemporary artist and Jesuit priest Fr. Jason Dy, SJ (b. 1977) at the Lopez Museum in 2017 where he restaged his installation Kanlungan ng Awa (Sanctuary of Mercy) (2015), a collaborative installation together with the communities of the Kristong Hari Parish in Commonwealth, Quezon City. The work depicted an improvised altar with a tabernacle constructed from reused plywood such as doors from local constructions, painted in gold. On the floor was a carpet of contributed blankets, curtains, and other textiles no longer used by the community, all conscientiously stitched together. Above these, a group of transparent plastic filled with air and written prayers from people hang like flying lanterns. The chapel in its original mounting was utilized by the parishioners not only as a site for communal collaboration for the work of art but also as a sacred space. The participative installation became a sanctuary as the work of art transformed into a site where one could pray and keep vigil. Truly, holiness may be found everywhere.

As a self-taught artist, Fr. Dy trained himself by immersing in workshops, classes, conferences, and exhibitions. His most recent exhibition Nature is never spent is a continuation of his artistic and ministerial service. From August 6 to September 11, 2021, the Vargas Museum in Quezon City presented installations of common flora, paintings on flour sacks, drawings on paper, lightboxes, mixed media on board works, archives of prayer intentions, and documentation of altar floral arrangements posted in social media by the artist. The exhibition is an extensive display, covering the ground, third floor, and basement of the museum, and is described as “a way to reflect on the condition of nature in pandemic time, or on the pandemic in natural history.” Today, as Manila finds itself yet again within the throes of the insistent global pandemic, Fr. Dy’s exhibition proposes a recollection of the multifaceted relationship between man and nature by uncovering the ineffaceable spirit amidst today’s ominous geographical, social, political, and moral climes.

Due to the lockdown, I had to book an appointment with the museum to be granted access to the exhibition. As I entered the ground floor gallery, I realize I was the only visitor at the university museum that day, let alone the campus as students and teachers have all but relocated academic activities into the digital realm. Despite the unnerving quietness pervading the once-crowded museum spaces, there was some excitement at the prospect of being able to immerse one’s self in the empty galleries without social constraint, offering a much-needed break from worldly noise.

Solemn Days, Feasts of Martyrs, Good Friday and Palm Sunday, Christmas/Easter, Ordinary Time, Advent,

116.53 x 32.28 in/296 x 82 cm, Acrylic and industrial paints on primed and handsewn sako ng harina (flour Sack), 2020

In the gallery lobby, an installation of suspended tapestry with leaf prints in various colors of green, violet, rose, white, gold, and red opens the exhibition. Upon closer inspection, each of the hangings is made of hand-sewn local flour sacks stamped with prints in acrylic and industrial paints from surfaces of leaves. The colors of the work all represent liturgical rubrics used in vestments or hangings which symbolize moods ascribed to the seasons of the year in the Catholic faith. Lent (2020) and Advent (2020) in predominantly deep violets connote solemnity, Ordinary Time (2020) in green implies anticipation and hope, Christmas/Easter (2020) and Solemn Days (2020) in white are ascribed to purity and birth, and Feasts of Martyrs, Good Friday and Palm Sunday (2020) in rose signify joy and love. The choices of leaf prints as patterns also imply the mood of each season, their formal qualities of wistfulness or boldness expressive of the time they represent. Priestly vestments or church hangings are typically constructed with simple cotton or wool to exquisite silks or satins and are sometimes adorned with semi-precious stones, but Fr. Dy’s series of stitched flour sacks and prints of found leaves might point towards finding sacredness in all things, simple and available.

On the upper floors, the series To Cry Over a Dying Leaf (1-5, all 2020), featuring framed photographs of single leaves in states of decay over a white background, are lined up on the wall of the landing. Capturing and focusing on a single leaf of anahaw (Saribus rotundifolius), anthurium (Anthurium andraeanum), pin-stripe calathea (Calathea ornate), dracaena fig (Ficus pseudopalma), and magnolia (Magnolia gallienus grandiflora), the images of leaves are portrayed in their most natural state: deforming, drying, and decomposing. In their usual environment, it is easy to dismiss dried leaves as worthy of attention, yet by placing them as aesthetic subjects, we are allowed to see their natural impermanence in a memorialized state. “To cry over a dying a leaf” thus seems an impractical reaction to mortality—as with every falling leaf is the blooming of another. Every end is a rebirth.

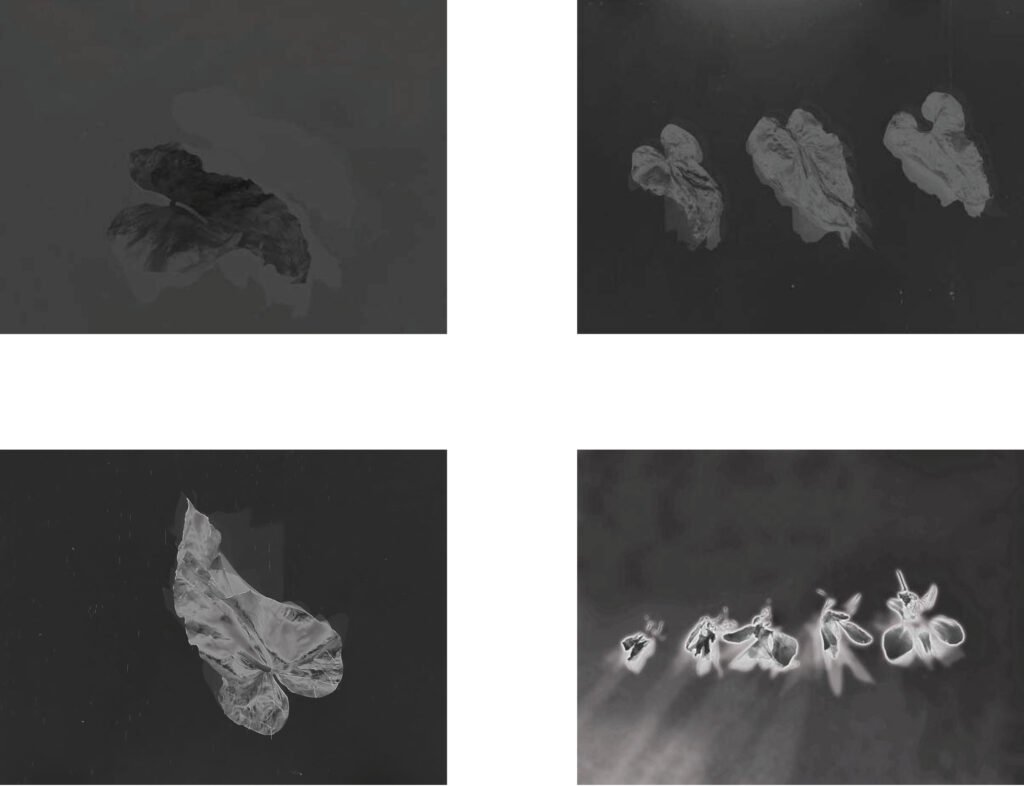

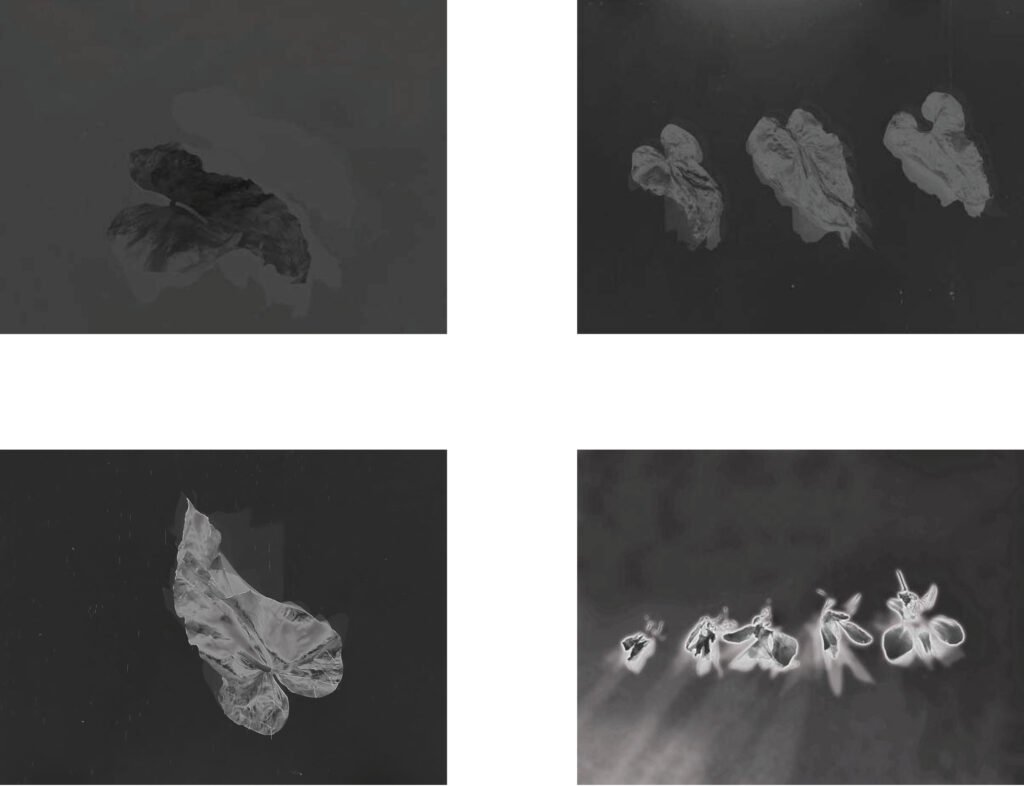

Arriving at the third-floor landing, one finds a series of lightboxes titled Auratic Series (1-5, all 2021) with images of leaves and flowers in black and white with contrasting chiaroscuro. The works Holy Wednesday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Easter Sunday show flora in a whitish glow amidst the shadowy background, save for Black Saturday showing the leaf darker than its surrounding space. The series directly references the days of the Holy Week, the darker illustration of Black Saturday implying the death of Christ, and transition to resurrection. As lightboxes, the images seem to recall x-ray films—an invitation to dissect the works not only from the surface level but to its core, as archetypal depictions of light and dark: the light of the leaves becoming metaphors in the reflection of Christ’s passion, death, and resurrection.

To Cry Over a Dying Leaf Series, 11.7 x 16.53 in/29.7 x 42 cm (framed), 2020

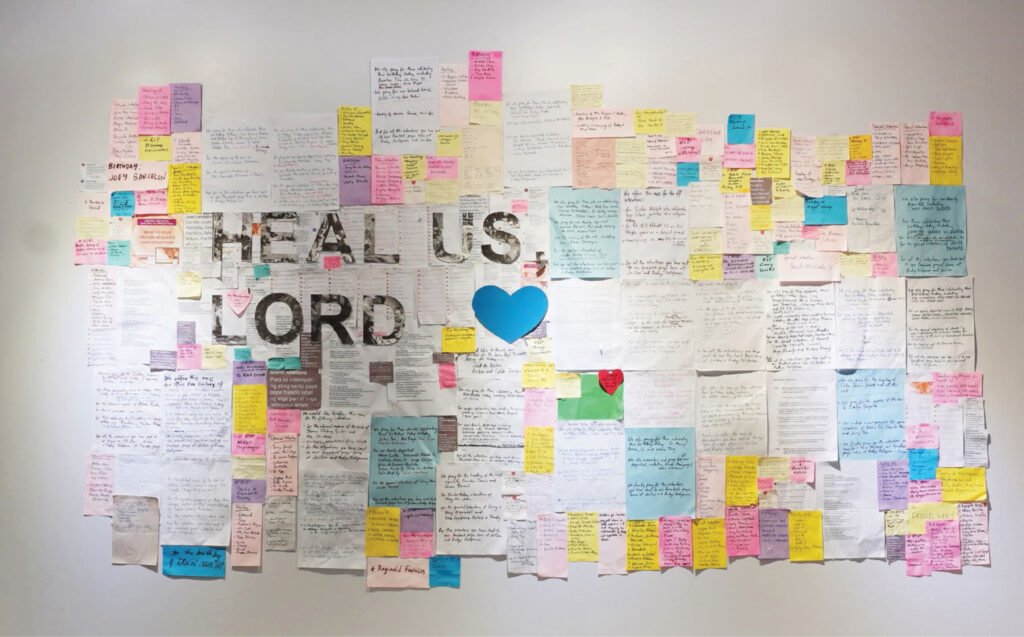

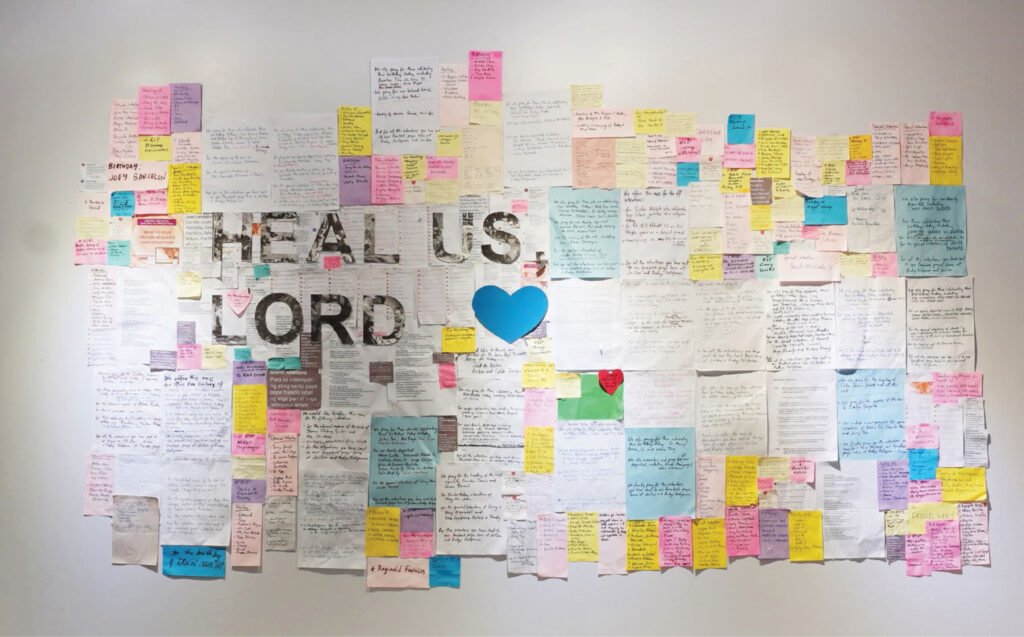

Further up into the third-floor gallery is Heal Us, Lord (2020) a wall-mounted installation of collected ephemera including prayer intentions from online, that were sent to Radyo Katipunan during the height of the pandemic. A black and white cutout of images showing frontliners, spells the work’s title. The installation gathers requests from birthdays to death anniversaries, as well as prayer intentions for those affected by the global pandemic. The installation of handwritten notes not only records the preoccupations of the faithful during a very specific time in the global crisis, but suggests a celebration of life, remembrance in death, and a shared hope for the healing of the world.

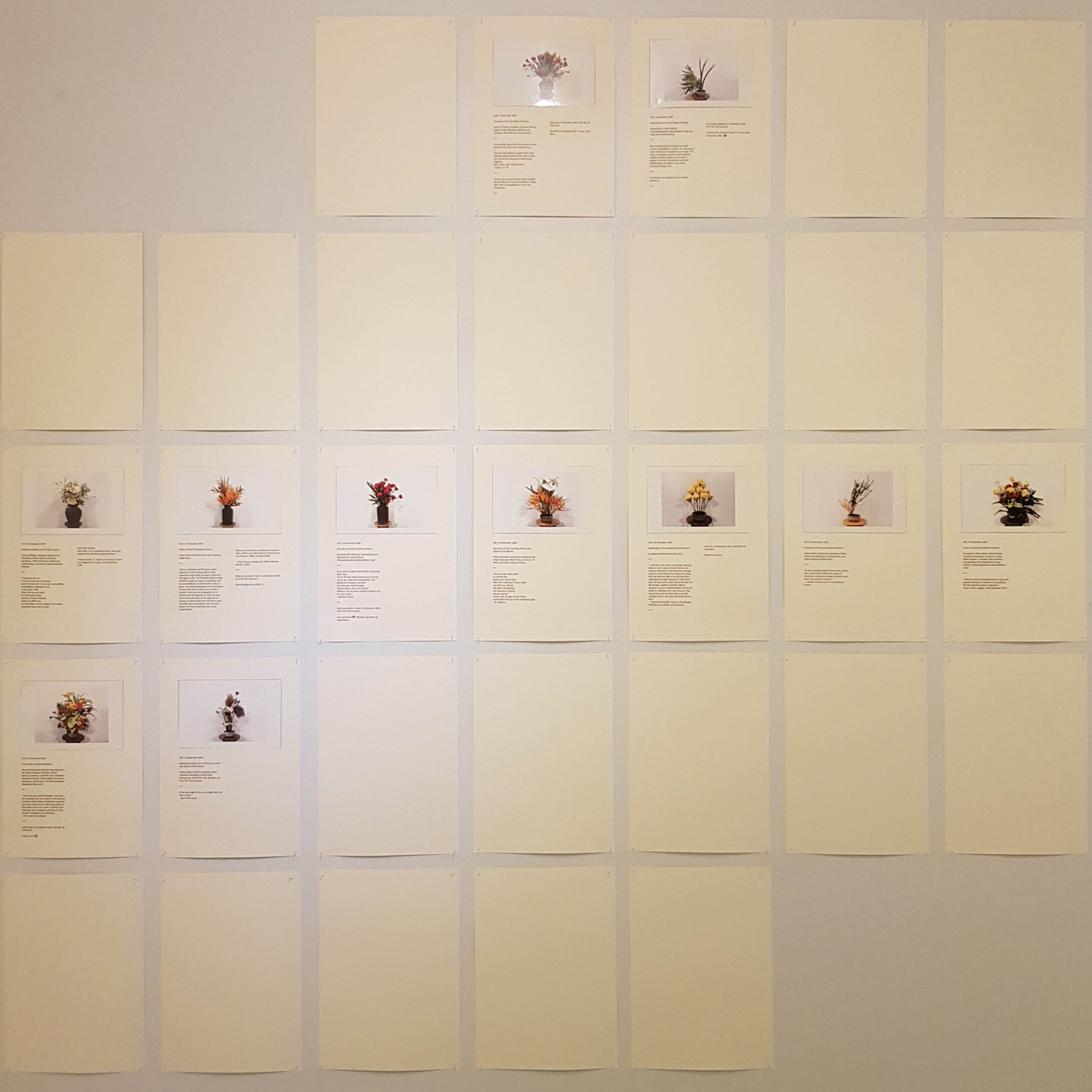

Fronting this installation is a collected archive of Fr. Dy’s social media series Arrange / Enliven (2020-2021) posted chronologically on the gallery walls. Originally posted daily on Facebook since 2020, he photographs his flower arrangements installed on the altar of the online mass of Radyo Katipunan. At 315 posts and counting, each floral arrangement is dated according to the day of the liturgical calendar, often citing poetry, quotations about spirituality from clergy, statements about current events, and even excerpts from his homilies. Inspired by the Japanese ikebana from the 7th century which was often offered at the altars, the arrangements exercise the principle of using three main lines: shin or heaven (the tallest or central stem), soc or man (middle), and hikae or earth (representing ground).

Auratic Series, 16.53 x 11.7 x 3 in/42 x 29.7 x 7.62 cm, Light box, 2021

Browsing through the printed archives, I find myself engrossed in the prevailing solemnity of each work. In Easter Monday (posted April 15, 2020), Fr. Dy gathers together kalachuchi (Plumeria flowers), walking iris (Neomarica longifolia) flowers, and unidentified leaves as altar offerings. The shared image is accompanied by an excerpt from the poet Elizabeth Barret Browning’s Aurora Leigh (1856): “Earth’s crammed with heaven, / And every common bush afire with God; / But only he who sees, takes off his shoes, / The rest sit round it and pluck blackberries.” In Saturday, Octave of Easter (posted April 18, 2020), Fr. Dy arranges leaves and flowers of monstera (Monsterra pinnatipartite) red coral tree (Erythrina variegate), talisay (Terminalia catappa) and Siam weed (Chromolaena odorata) as altar offering and cites the following text from Pope Francis: “[…] if we feel intimately united with all that exists, then sobriety and care will well up spontaneously.” In Saturday, Third Week of Easter (posted May 2, 2020), Fr. Dy chooses leaves and flowers of bromeliad (Bromeliaceae), helicona lobster claw (Heliconia), and anthurium stems (Anthurium) as altar offering and shares this with a text from Fr. Dean Brackley: “These turbulent times disclose our need for a discipline of the spirit. To respond to our world, we must get free to love. That involves personal transformation, which includes coming to terms with evil in the world and in ourselves, accepting forgiveness and changing.”

Each day, Fr. Dy gathers these plants from the garden of the Jesuit Residence and the grounds of Ateneo de Manila where he teaches Fine Arts, or sometimes are donations sponsored by friends and faithful mass-goers. Arrange / Enliven’s conscious arrangements appropriating the cosmological philosophy of ikebana, offering as altarpiece, and later sharing to the public digitally might seem tedious work for one man, yet guided by the notion of service and ministry, Fr. Dy’s arrangements as offerings are laden with inspiration and devotion, a humble attempt to understand man’s relationship with and the nature of the divine.

Finally, in the lowest level of the museum is the installation Bloom (2021) positioned in the open-air basement space. Gathering white mum (Chrysanthemum) flowers to spell out the word “BLOOM” in bold capital letters, the work is left to wilt and dry on a green wall. In states of decay, the once white flowers have all dried up this time, the word suggesting not merely a transient description of the state of flora, but a willful intention, or even a commanding request: perhaps the resounding intention is directed not towards the flora, but to its viewers. Like a prayer, the work asks us for our human capacity to learn from mistakes, heal, and grow.

In an interview on his project for Arrange/Enliven with art initiative Load na Dito and published in his online blog, Fr. Dy shares: “Like the traditions of the land artists in England and the ikebana masters of Japan, arranging flowers and plants into words, floral offerings, or botanical collages make me more sensitive to nature’s rhythm of life—seeds sprout, plants grow, flowers bloom, fruits rot, and leaves fall. As we learn from nature, human beings are not determined by nature’s laws. With creativity, intelligence, and freedom, human beings can positively impact the environment. The same is true with human greed, indifference, and abuse that destroy nature. Hopefully, we decide on the better option of caring for the earth and transform it to sustain all of life.”

Awaken/Enliven Series, Dimensions variable, flora specimen arrangement, 2020-2021, from top left to right: Easter Monday, Octave of Easter, Third Week of Easter, and Twelfth Week in Ordinary Time

Awaken/Enliven documents, 29.7 x 21 cm each, 315 pcs 4R (8.9 cm x 12.7 cm) photographs on ink jet-printed pale yellow 200 GSM paper (Artist Proof), 2020-2021

In the course of the pandemic, the world has seen countless suffering, not solely due to the biological impacts of the virus, but also its social and political consequences which range from inconsistent government responses, corruption, misinformation, and the visible inequalities in the community. On March 9 of 2020, the national government declared a public health emergency following the first local transmission of Covid-19. With more than 1.9 million cases and 33,000 reported deaths, the Philippines is expected to stay in various states of community quarantine with restrictions. The pandemic continues to affect the larger population, but also the arts and culture sector as many artists and cultural workers struggle to stay afloat financially. As of this writing, the Philippines reports a record number of cases as the Covid-19 Delta variant spreads.

This, I find, is why an exhibition like Nature is never spent a momentous endeavor at this time. In the exhibition text, the Vargas Museum notes: “The insistent global pandemic has made humans come to terms with an inter-species universe.” While the pandemic presented several obstacles—the curtailing effects of the lockdown, and the undervaluing of art and culture as “non-essential”—many still find hopeful ways to contribute to the community and find shared healing through artistic output or service.

In a Facebook comment for Fr. Dy’s floral arrangement Wednesday of the Twelfth Week in Ordinary Time (posted June 24, 2020), an excerpt from Saint Francis of Assissi stands out as resonance to the exhibition. It reads, “He who works with his hands is a laborer. He who works with his hands and his head is a craftsman. He who works with his hands, head, and heart is an artist.” Fr. Dy’s artistic mission might not solely be appreciated for its aesthetic and participative merit—its message and challenge of liberation rooted in mundanity, the grassroots, simplicity, and the everyday, speak of the omniscient and ineffaceable presence of spirit in all things. Nature is never spent does not express an oracular message from a single faith alone—it carries with it the unbreakable bond man shares with his fellows, and our collective potential to resonate with the divine. •

After George Kamel, SJ Series, 8.27 x 11.61 in/21 x 29.5 cm, Botanical collages on archival paper, dried and pressed flowers, leaves, and stems (unframed), 2021

Nature is never spent is on show at the UP Vargas Museum until September 11, 2021.

John Alexis Balaguer is an independent art manager, critic, and curator based in Manila. He is the founder of Curare Art Space, a digital space for curatorial collaboration. He was formerly operations manager and head of research at Palacio de Memoria, a heritage house turned arts and events center; curatorial writer and researcher at Ayala Museum, writing for exhibitions and publications, and acting as managing editor for the museum magazine; and gallery manager at Archivo 1984 gallery. Lex received the Loyola Schools Award for the Arts in 2012, and the Purita Kalaw Ledesma Award for Art Criticism in 2019. He currently contributes to Art Asia Pacific magazine, and Kanto.com.ph. On better days, Lex makes digital art and writes poetry.