Interview Patrick Kasingsing

Art Clemens Gritl

How are you? Please introduce yourself.

Hello, my name is Clemens Gritl. I work as an artist and architect in Berlin, Germany.

Please give us a brief background of your interest in architectural visualization.

I have been working as an architect for a couple of years, so I’m very familiar with 3D models. However, I was seeking a way to work artistically with CAD and 3D, as I find that these programs offer a lot of potential.

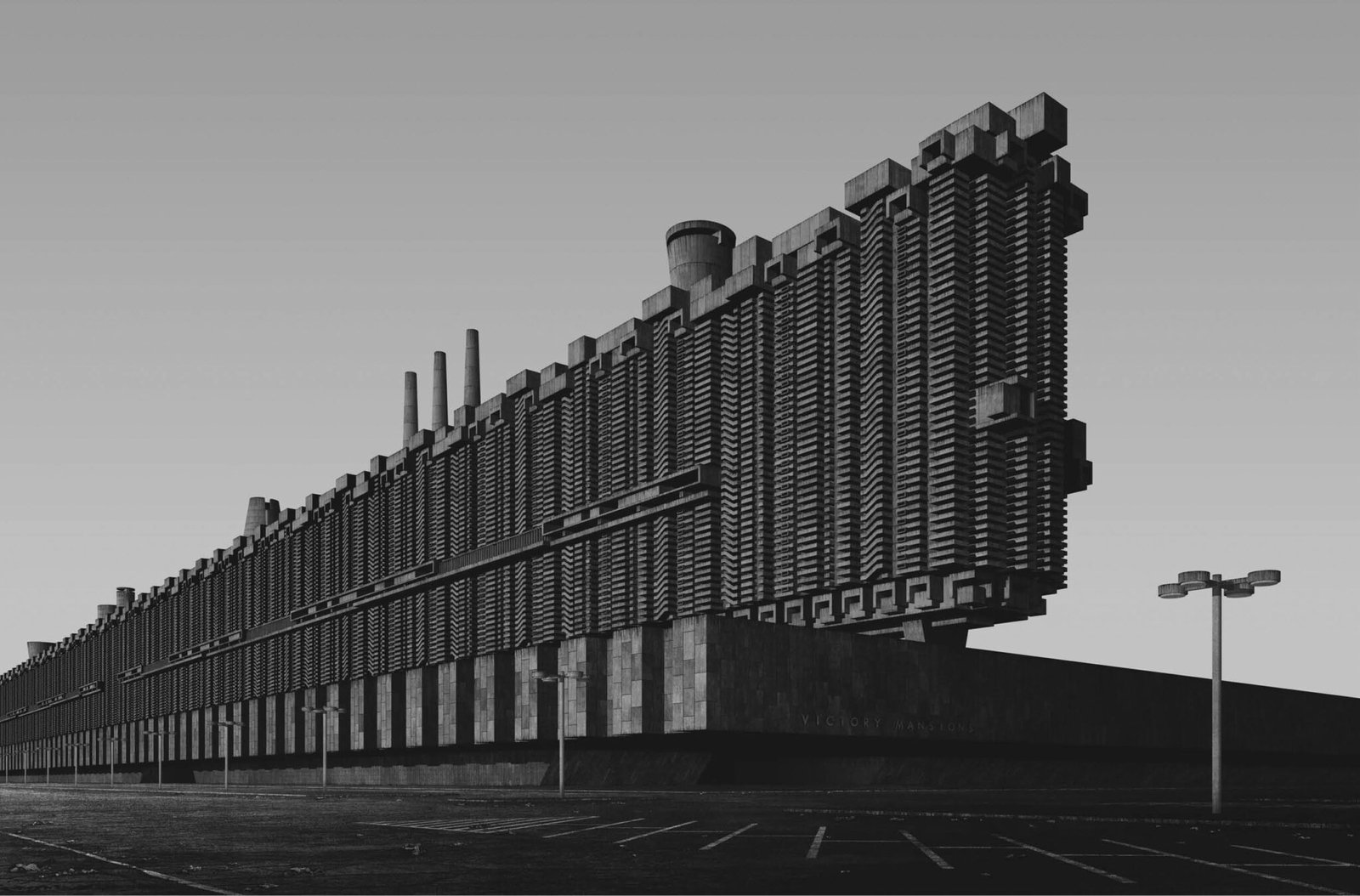

You have found fame for your conceptual 3D visualizations of imaginary Brutalist estates. What inspired the concept for such a project?

I studied in Rome, Italy—a city full of experimental, large-scale housing projects from the 60s and 70s. One day, I discovered ‘Il Corviale’, a huge, 1,000 meter-long apartment block made of concrete. I was intrigued by its concept and its contemporaries, even if a lot of them are somewhat dysfunctional, in a state of decay, or abandoned. I saw the strong social vision for these projects through their architecture.

What message do you want to send across with the project?

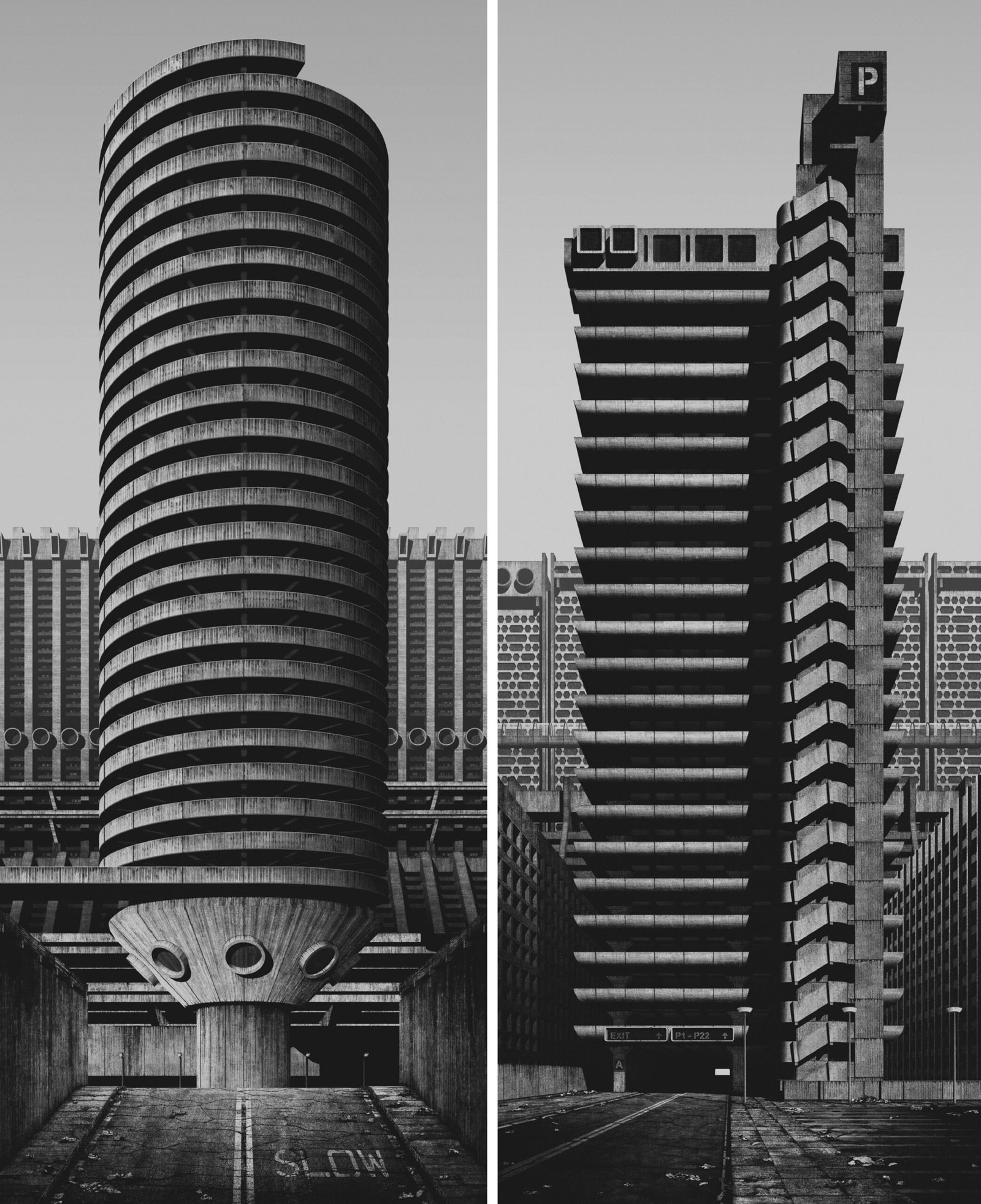

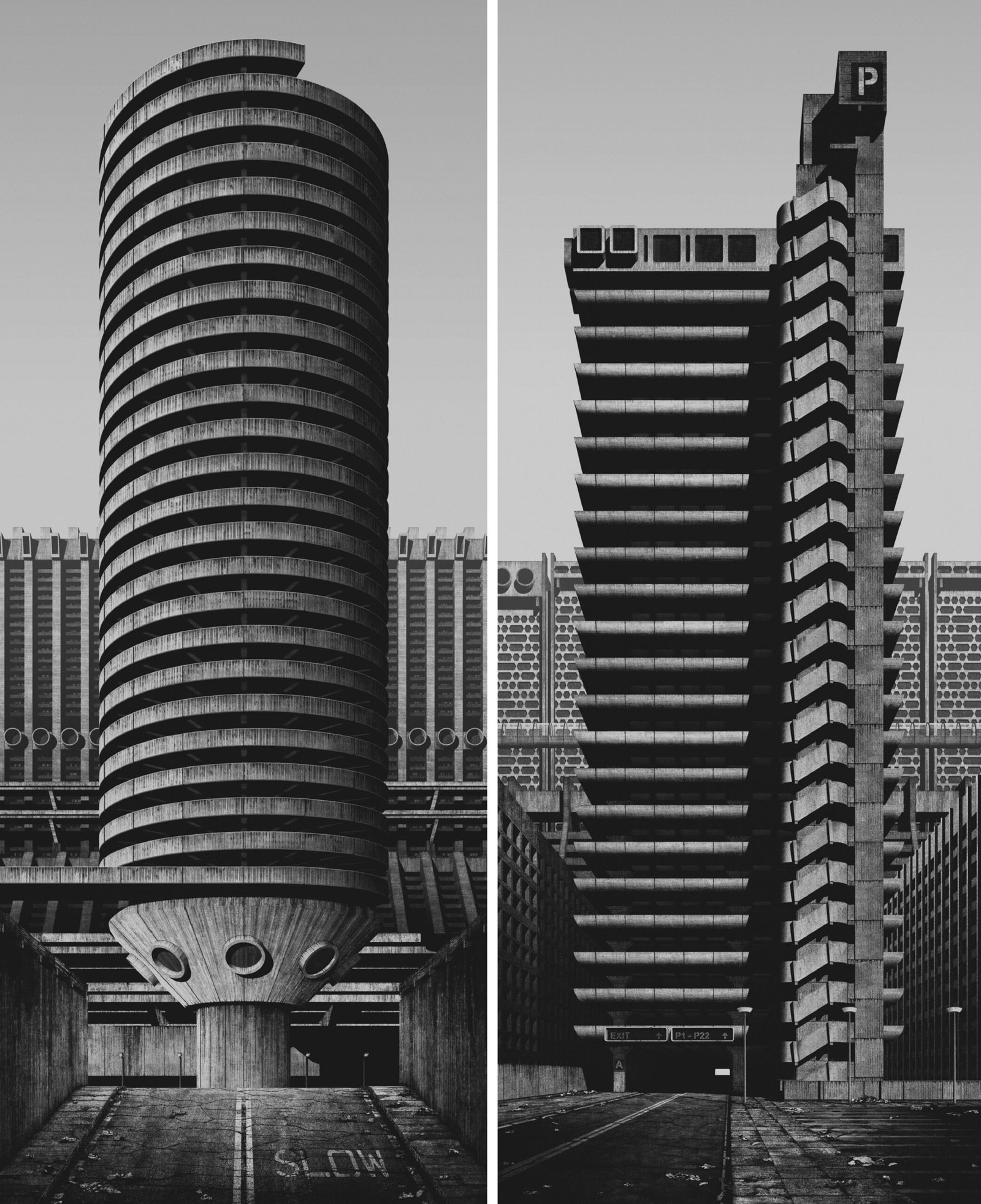

Most Brutalist buildings awaken contradictory feelings in me. While I am mesmerized by their radicalism, futurism, sculptural quality, and intransigence, I also see the lack of human scale, vivid public spaces, and a generally weak focus on community integrity and developing a sense of neighborhood. I am interested in expressing this tension through my artworks.

Why the Brutalist style? There is a prevailing image of it in the public eye as a style that’s too raw, unapproachable, and in the cases of failed housing estates, inhospitable. What made you decide to adopt it for your architectural utopia (or dystopia)?

Brutalism may be the strongest architectural language that ever existed. I don’t think the design world ever saw such an uncompromising style again. The architecture world has always been allured with the creation of utopian visions. During the post-WWII era, notably in the 1950s and 1960s, conceptual projects by innovative architecture studios (often wonderfully depicted in illustration) surfaced, intent on positing their futuristic visions of a perfect society. ‘Clusters in the Air’ by Metabolist proponent Arata Isozaki, Archigram’s ‘Walking City’ and Superstudio’s endless structure above Manhattan come to mind. The reconciliation between Brutalism as an architectural movement and architecture’s fascination with utopias seemed to me both an aesthetically attractive and thoughtfully provocative concept to build a project on.

Can you name some of your influences for the project, both for the concept and style of execution?

First of all, of course, a whole range of influential Brutalist architects like Le Corbusier, Paul Rudolph, Marcel Breuer, Bertrand Goldberg, and Juliaan Lampens. I was also greatly inspired by the utopian, futuristic designs and artworks of Boullée, Sant’Elia, Chernikhov, and the Japanese Metabolists like Isozaki. Dystopian novels and movies also helped shape the depiction of my architectural visions; films like 1984, High-Rise, and Metropolis come to mind.

The approach of the New Topographics photography movement, especially the work of Lewis Baltz, directed my attention to surface structures and dramatic shadowing. Of course, I cannot discount the impact of the various cityscapes that I’ve discovered and lived in.

Let’s talk about the design process for these intricate artworks. Can you briefly walk us through the steps to create your digital illustration from start to finish?

The process can be structured into three parts. The first part is the most difficult one: sketching and designing the buildings and the cityscape that surround them. The second part consists of translating these sketches into 3D models, and finally, the last stage involves retouching via Photoshop.

The project also serves as a commentary towards the plasticity and facadism of today’s architecture. Are there any other particular issues in the industry that you think should be brought up and discussed?

One thing I appreciate about some of the best Brutalist buildings is their noticeable craftsmanship and construction quality. These buildings were built to last. Today, sustainability is on everyone’s lips, but nearly every newly-built project only has a lifespan of fewer than 30 years. Interiors are even designed to last just ten! I think it is high time we discuss the usage of long-lasting materials and efficient construction methods again, instead of disposable low-quality products and construction practices that only prioritize speed at the expense of project quality, longevity, and the environment.

This issue delves into mental health. As an architect, what issues do you think should the architecture industry address when it comes to the mental health and wellbeing of its practitioners and finally, its users?

First, and as mentioned previously, a reorientation towards naturally-occurring and longer-lasting materials is absolutely essential in creating spaces that are hospitable and livable. Secondly, we need to build and develop mixed-use neighborhoods again. There’s a reason why 19th-century districts in Europe worked.

Architecture that encourages variety and diversity, social interaction, and is created with respect to the human scale can create comfortable environments for everyone to flourish with health and dignity. •

More of Clemens’ brutal urban visions at clemensgritl.com and on Instagram at @clemens.gritl

*Originally published in Kanto No. 2, 2018. Edits were made to update the article.