Interview Miguel Llona

Images Design Center of the Philippines and Estudio Ruiz Design Co.

The present pandemic has revealed the shortcomings of our current systems and has put the spotlight on new methods, materials, and concepts that are more sustainable and compatible with the new normal. Although not altogether a new concept, interest in circular design has risen as of late for its ability to account for all stages of the design process and create zero waste. Design Center of the Philippines, in line with its mandate to foster design innovation, and to help encourage the transformation and commercial viability of indigenous materials, put two and two together with an intensive, two-day circular design challenge centered on a promising plant-based material: bakong.

The Bakong Circular Design Challenge offered Filipino creatives of all stripes an opportunity to craft solutions-based design while taking to mind the goal of zero waste. The challenge is supported by four pillars that all participating ideas had to adhere to: Circularity, Innovation, Culture, and Femininity. Ten finalists from the participants pool were then chosen to advance to a two-day Circular Design Challenge workshop, where DCP executive director Rhea Matute, Bakong Creative Director/Circularity Expert Carlo Delantar, and Panublix’s Noreen Bautista among others brought thought leadership to attendees.

The program culminated in the recognition of three winners: Malayana, Modabako, and Brakong, with each team making the best of bakong’s material potential while keeping an eye on its economic and environmental impacts. The three winners will be granted technical assistance from DTI FabLab for the prototyping of their products, as well as a chance to exhibit them in the first ever Sustainability Solutions Expo to be held in November 2021.

Kanto was granted an exclusive interview with circularity expert Carlo Delantar and public relations specialist Angie Tan on the basics of circular design as well as their experiences and observations from taking part in the Bakong Design Challenge as panelists.

Hello Carlo and Angie! Welcome to Kanto! Tell us, what convinced you to hop onto the circular design track? What did you see in it that convinced you both to champion it?

Carlo Delantar: The world is only 9% circular. This means the world is wasteful with its resources. We knew later on that our wasteful habits can create tremendous impact on our lives while also affecting the lives around us.

We must be inspired by how nature works and how a natural symbiosis with nature and society can create a perfect balance, one that can bring us to an equitable and just society where our planet thrives.

Angie Tan: I love the approach of circular design on sustainability. What drew me into this model is that materials don’t need to end up in landfills.

How can something be considered circular design? What features or elements should it have, and how should it benefit society?

Delantar: An example of circular design must adhere to these three principles: 1. Designing out waste, 2. Keeping the product in use, and 3. Regenerating natural systems, basically ensuring that we take into consideration what happens to a product or a material long-term in the design process.

Historically speaking, our society was circular to an extent but when industrialization came, the abundance of resources shifted our ways towards growth that ended up hard to slow down.

Now we are in a space where society sees the importance of well-designed products that adhere to the circular economy principles.

Tan: Something can be considered circular design when it no longer adheres to a typical product lifecycle, ie, it has no beginning or end.

DCP’s Materials Research and Development Program

Text from the Design Center of the Philippines

The Design Center of the Philippines has undertaken research and development activities to convert various indigenous materials and agricultural wastes into semi-processed materials that may be utilized by MSMEs to develop and improve their products. Section 4 of RA 10557 states that Design Center is mandated to develop and maintain a creative Research and Development Program to improve Philippine products and services, including those created by the MSMEs, and conduct continuing research on the product, materials, and processing technologies. A strategic direction of the research work is towards supporting the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, which also supports and underlines the value of “malasakit” as defining the value of Philippine design.

One of the key areas of Design Center’s work is in Materials Research and Development. With a firm belief that materials are the building blocks of design, the research team is committed to advancing the design agenda through research and development of new materials using local raw materials, particularly agricultural by-products, in order to create value and to drive the progression of economic value and complexity, while adhering to principles of sustainability.

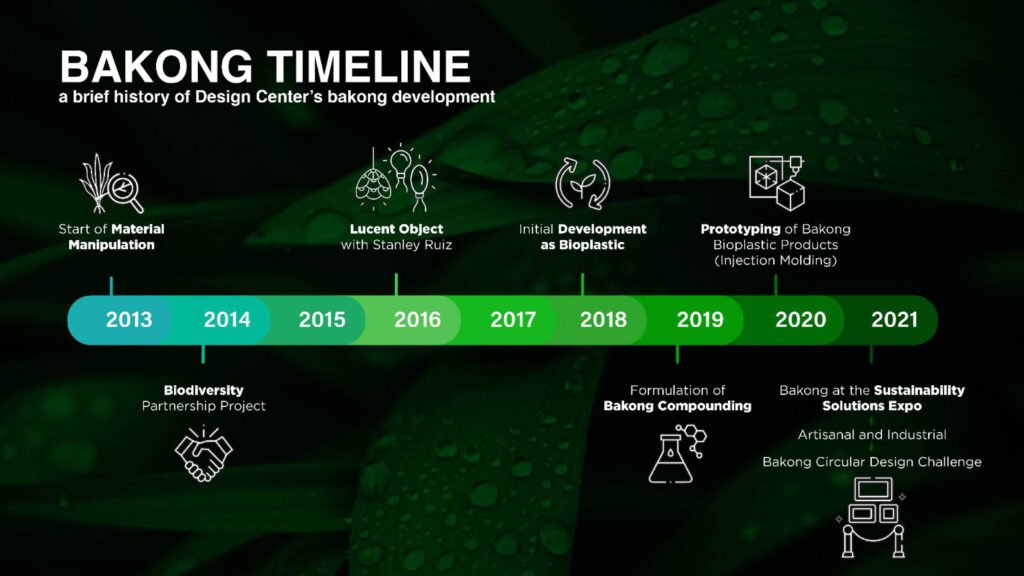

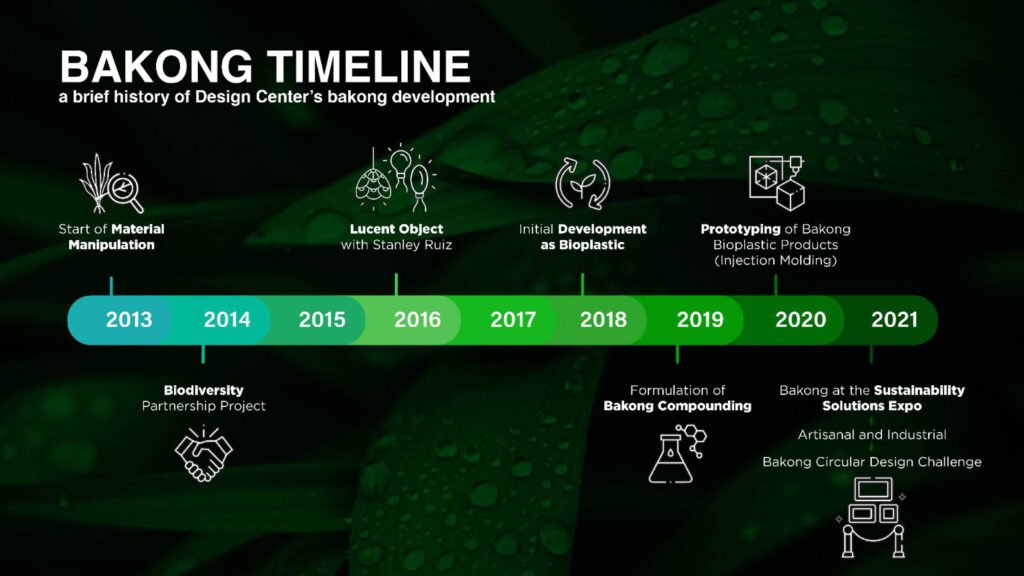

One of these indigenous materials is bakong. Bakong (Hanguana malayana (Jack) Merr) is a perennial, widespread aquatic plant that grows up to 3 meters in height [Leong-Sˇkornicˇkova and Niissalo, 2017] and found locally abundant in Sta. Teresita, Cagayan. According to Co’s Digital Flora of the Philippines, bakong is present in other parts of the country, such as Mindoro, Palawan, Lanao del Sur, Agusan del Sur, and Surigao.

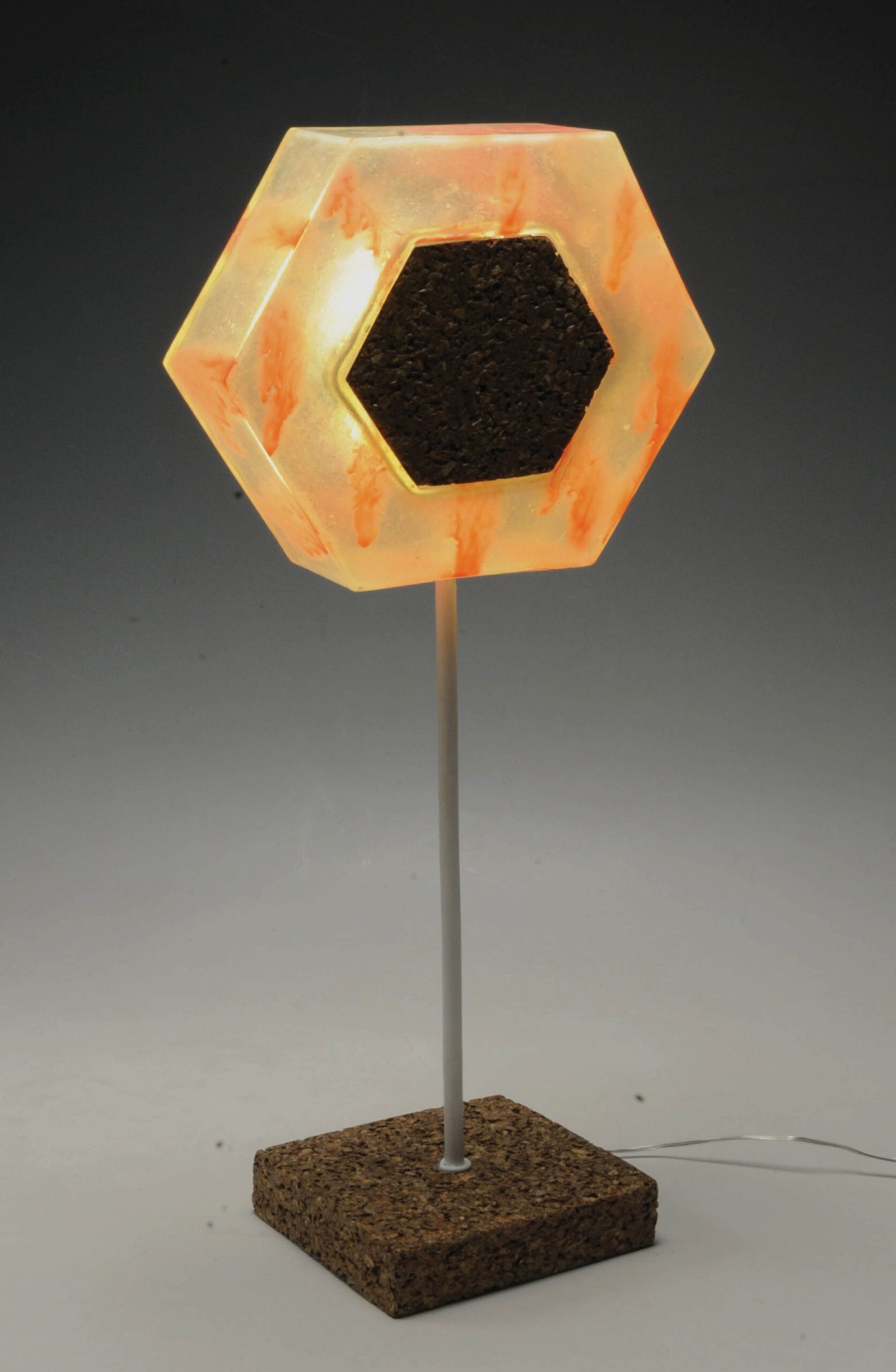

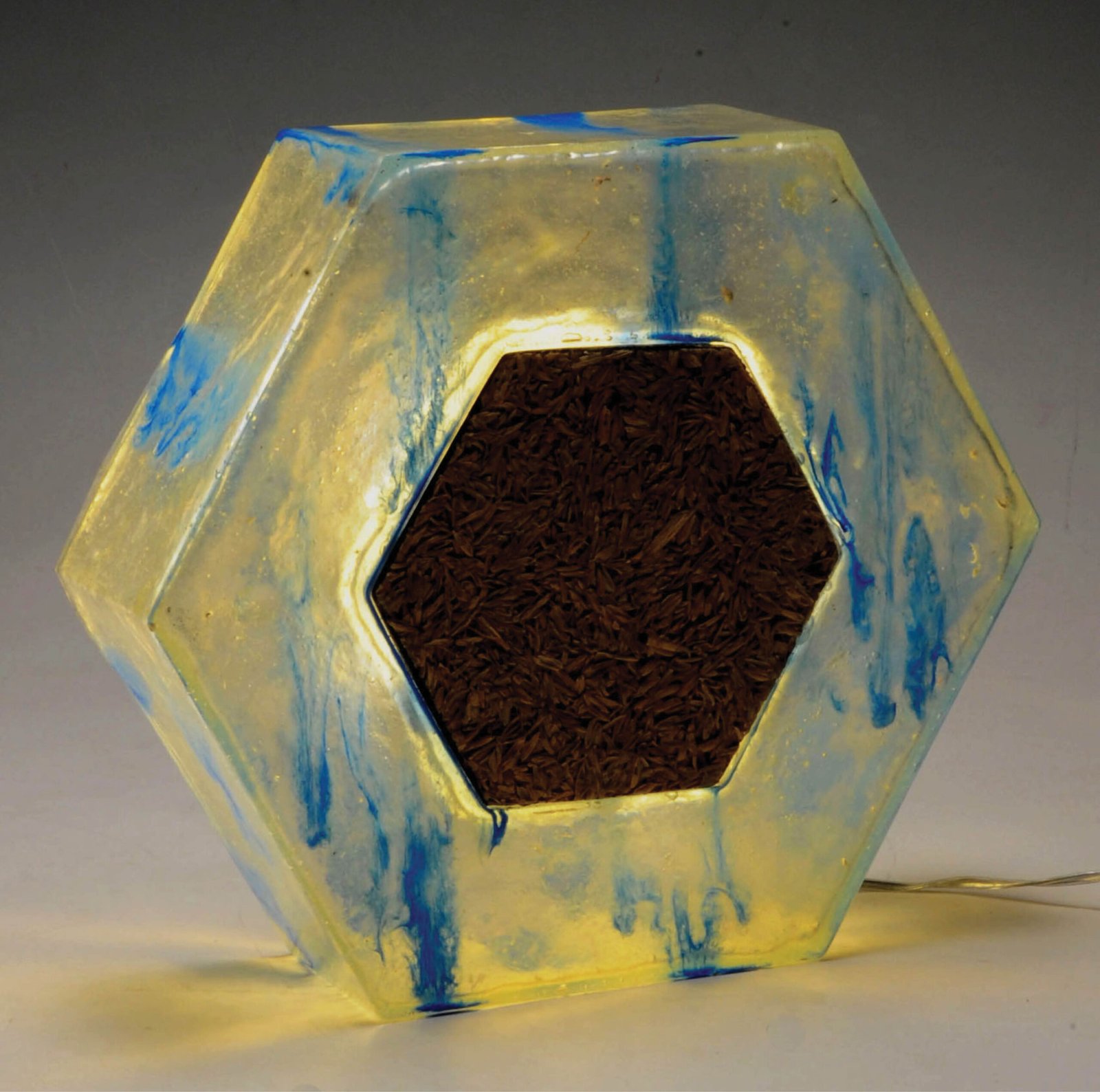

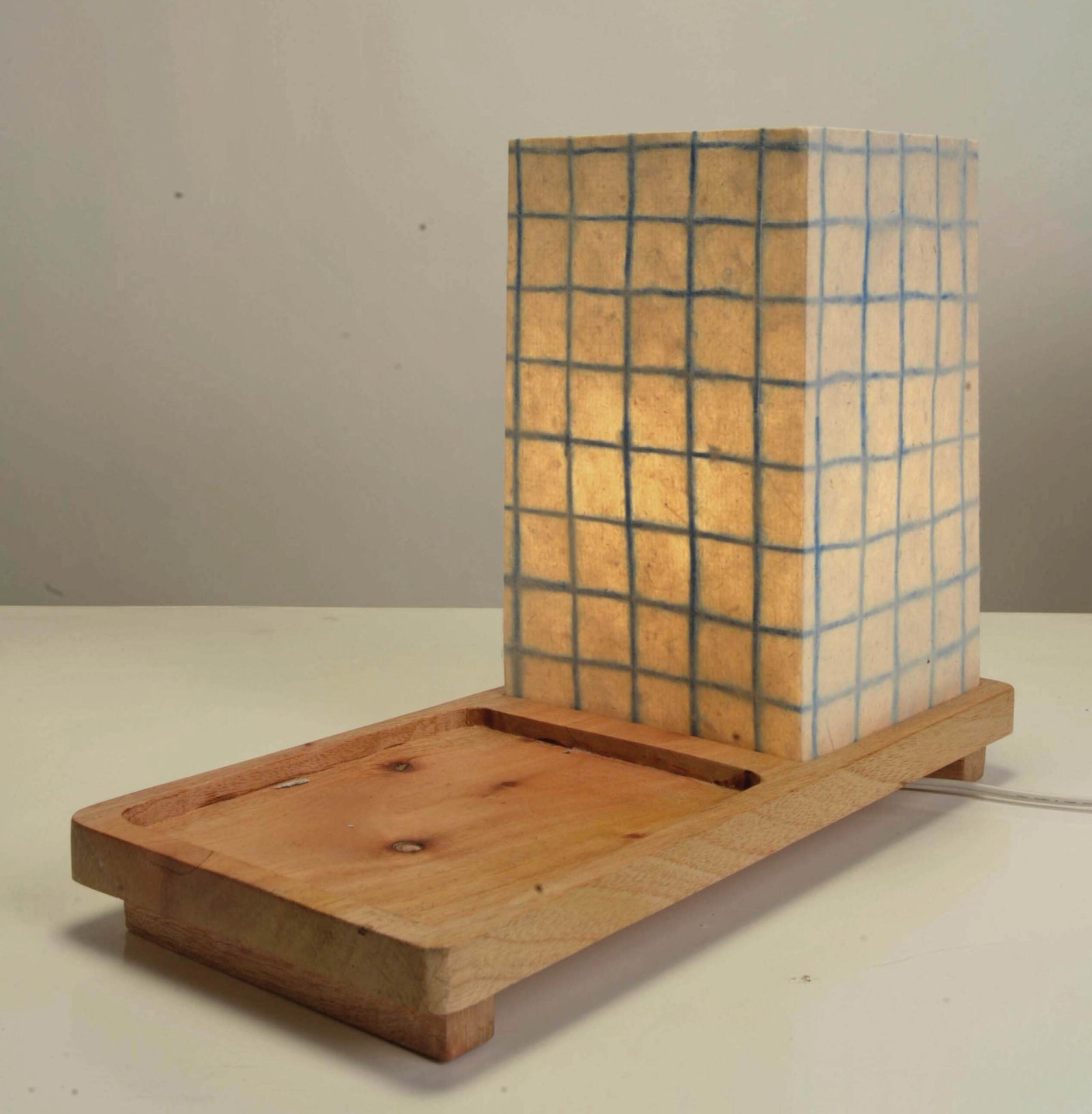

The local people in Sta. Teresita Cagayan considered bakong as an obstruction in Bangalao Lake; thus, the LGU, through DTI-Cagayan, sent a formal request to Design Center to check if they can find value to the plant. The Materials Research team conducted several experiments and manipulations using bakong leaves and stems and successfully converted the plant into useful and commercially viable products. The Laguna De Cagayan Handicraft Association adapted the process and techniques in converting bakong into semi-processed materials and create new economically-viable products. The community produces semi-processed materials such as braided and twined stems, fibers, handmade paper, pre-treatment, and dyed material. Semi-processed materials were utilized as the raw material for artisanal products such as lamps and lightings and were showcased in the 2017 edition of Manila FAME to show how material research and design can add economic benefit to the community in Cagayan as well as Philippine exporters of wearables and homestyle.

What are some notable examples of circular design? Does it differ from sustainable design?

Delantar: In a way, circular design is sustainable design while sustainable design promotes circular design. Circular Economy is Sustainability 4.0.

Tan: The most notable example of circular design for me is Plastic Bank. I also see it in some fashion enterprises. Yes, it differs from sustainable design in that circular design is but one of the many approaches to sustainable design.

How far along is the Philippines when it comes to circular design, in terms of creating initiatives for it and raising awareness of its benefits? What steps do the government and other relevant authorities need to take in order to help promote the viability and spread of circular design?

Delantar: It’s hard to measure where the Philippines is when it comes to circularity for the reason that empirical data pertaining to it is hard to come by. Where we can proactively promote circularity is where the highest emissions in the Philippines are created, most of which come from the energy and agriculture sector. These two sectors can be managed more efficiently so as not to cause unnecessary harm to the environment, with practices and policies that empower the workers and local communities to act sustainably.

Tan: I think we’ve barely scratched the surface when it comes to circular design because sustainability, in general, is still not relevant to the majority of Filipinos. For circular designs to become viable, I think the government should first push sustainability into the national agenda, and then create incentives around it.

Why was the bakong plant chosen as the material to be worked with for the Circular Design Challenge? What are the properties that give it potential as a material with various applications, and make it ideal for a circular economy?

Delantar: Bakong is native to the Philippines and most abundant in the Cagayan region. It’s a material that’s never been extensively explored before, at least never in this scale and never with circularity as one of the main intentions. Its vast potential is virtually untapped and that’s the aim of this bakong project―to stretch the limits of bakong―its materiality and its circularity, to find out where it sits in the Filipino culture while rooted in the values of a feminine economy.

The Design Center of the Philippines has also developed a variation of bakong as a material, which is bakong bioplastic. Did any of the teams also work with bakong bioplastic for their design solutions?

Delantar: Yes, the beauty of a new material is exploring its potential applications through any sector. Plastics having a big carbon footprint and low utilization; bioplastics are largely being explored to find ways to be an alternative to plastics. Outside of single-use plastics are durable bioplastics that adhere to circular economy principles. Exciting implications range from better design solutions to artisanal innovations.

Three teams shone above the rest in the Circular Design Challenge. What separated them from the other participants, and what were the innovations that they were able to come up with for bakong as a material?

The three teams stood out because they were the ones that really embodied the four pillars of the project (Circularity, Innovation, Culture and Femininity), and their ideas were deemed to be the most compelling and feasible given the current manufacturing and material constraints.

Brakong – prosthesis for cancer survivors

Modabako – modular and flatpack furniture

Malayana – lighting pieces that feature and collaborate with the Cagayan community where bakong is from

The teams underwent a series of workshops to help them come up with their design solutions for the challenge, which include workshops for design thinking, circular strategies, and pitching. What are the skills and knowledge being imparted by these workshops to the participants, and why are they necessary?

Delantar: At the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, their role is to bring Circular Economy to the zeitgeist of society. Their Circular Design initiative aims to reach 80 million designers out of 160 million estimated designers globally. Reaching 40 million designers to be aware of Circular Design while empowering 20 million of these designers to apply circular design would create a power shift in how society perceives and designs products and services.

Designers play an integral role in which the world operates, and intention is the starting point―this is what we hope to achieve from the Circular Design Challenge. We continue on as advocates for the Circular Economy in the Philippines.

Tan: The main benefit for me is grounding their product designs to human truths. Most of them came into the challenge with a product in mind. The workshops allowed them to ground their products in market realities that will allow their products to become viable in the market.

How will the knowledge from these workshops help them even outside of the Circular Design Challenge?

Delantar: Mind setting is always a good way to start as consumers demand more responsibly-made products. Designers and manufacturers must adapt. The shift is already starting. Consumers are leaning towards brands and companies that provide transparent, accountable, and sustainable products and services. Companies are trying to catch up and of course, when demand is there, supply will eventually follow, and hopefully circular at its core.

What we saw emerge during this challenge would be an emergence of Bakong’s own circular economies respectively in textile/fabric and bioplastics. The winners can rely on the supply chain in the Philippines that can adapt a circular economy with an emerging circular infrastructure that can pioneer a truly circular supply chain for other materials and sectors to follow.

Tan: Having a human-centered approach to solving problems and having that training to balance big thinking with granular thinking

What were the industries or sectors that you hoped would benefit most from the Circular Design Challenge with its exploration of bakong as a material? Did you guide the teams toward designing for specific industries or applications?

Tan: I hope to see the FMCG sector benefit the most from this because most of our waste comes from these industries.

Circular designs can already be considered important before the pandemic, but has their importance taken on more weight in this new normal? Do you believe that they could be the key to creating a better normal? If so, why?

Tan: Yes, it carries more weight in the new normal and plays a pivotal role in creating a better normal because at the root of the pandemic is really the way we consume.

Delantar: The pandemic showed us that we can live life with the bare essentials while showcasing how technological advances can make our lives convenient and comfortable. With all these factors put together, we can recalibrate how our lives operate. Change is always unpleasant. A good example of this is the current work-from-home arrangements companies were forced to implement due to the pandemic; initially, there was fear that it may impact work productivity and affect the economy, but studies showed that this is largely not the case and that it is more than possible to design our lives in a manner that works well for us and everything around us.

The awareness and tools we have now are enough to live a life that can help the planet thrive for generations to come. •

Miguel Llona is a writer who has written for numerous print and online publications. He was a former editor at BluPrint magazine, and now serves as a marketing consultant for an interior design firm.