Interview Vanini Belarmino

Images Pitchapa Wangprasertkul

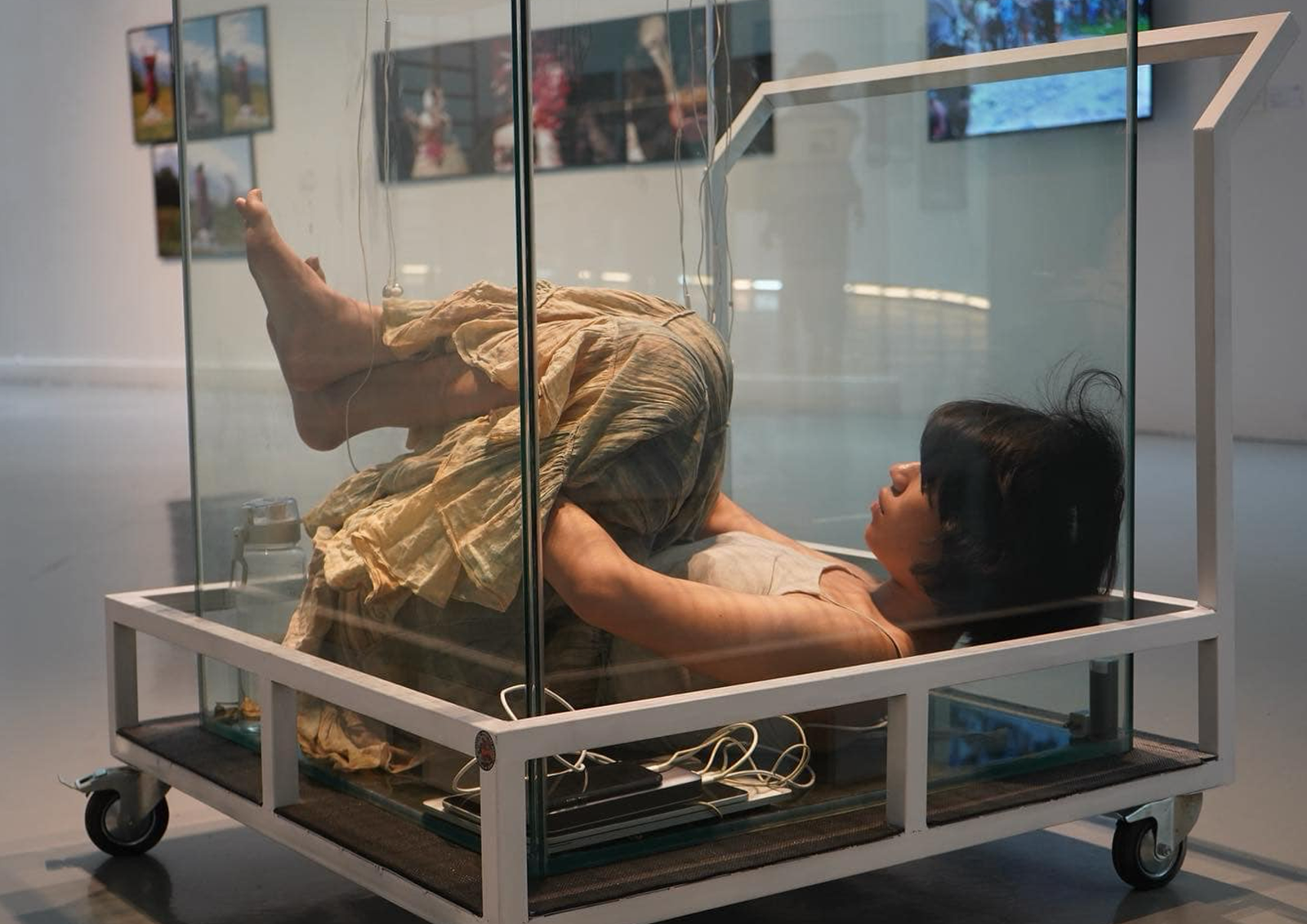

In The Standard, Pitchapa Wangprasertkul positions herself inside a glass case mounted on an industrial push cart, navigating the tension between visibility and confinement. The work references both the display mechanisms of contemporary art fairs and the cramped, highly regulated spaces of family homes, particularly in the Philippines. By recreating a labourer’s environment with only the bare necessities, the durational performance highlights societal “standards” imposed by authorities or structural systems—ranging from minimal living spaces to curtailed rest—that shape daily life and endurance.

Originally presented at the Bangkok Art Biennale 2022, The Standard is now recontextualised for the Philippine setting, inviting audiences to reflect on domestic and social pressures, resilience, and the boundaries between care, labour, and survival. Within the thematic framework of Mothering/Unmothering, the work resonates with the negotiation of constraint, expectation, and endurance in domestic spaces and relational care.

In The Standard, you position yourself inside a glass case on a push cart, caught between being on display and feeling confined. How does this tension—between visibility and containment—shape your experience and approach to the performance?

Pitchapa Wangprasertkul: In The Standard, as well as in several of my other works, including my recent artworks in 2025 (Things Left to Stay, 2025; If the Shoes Fit, 2025). For me, confinement is not only a condition but part of a method in my practice to emphasise the impact that space has on the human body. Performing inside a limited space is not meant to simply represent discomfort or oppression.

My intention is not to show how the space is used to trap my body. But rather to make the process of adaptation more visible. When my body has no other choice but to accept the conditions of the environment, it begins to change, altering how I move, touch, and explore space.

The body that has known the space through duration is very different from the body that is suddenly forced into confinement and wants to escape. When movement comes from learning and adaptation, the body is transformed, and the person in that space begins to move as she truly belongs there.

Visibility allows the audience to witness this process. I think the first thing the audience might feel from this work is the immediate tension of seeing the human body in confinement. But over time, they will begin to notice how the body starts to adapt, or might already have adapted, to the space. This adds the weight of time/ duration to the performance. So, what the audience observes is not only a body inside a confined structure, but also a body negotiating, exploring, and testing its own limits. I think it really represents how humans attempt to adapt themself even in a restrictive or even cruel environment.

In the context of Mothering/Unmothering, what was your first impression of the exhibition’s title? How do the ideas of Mothering/Unmothering resonate with your own practice and perspective?

My first thought about Mothering/Unmothering was that it explores women’s roles and the expectations attached to them.

For me, the word ‘mothering’ emphasizes especially feminine energy associated with the power of giving birth, and creating, not only life but also ideas and artistic work. More importantly, mothering is about nurturing life.

At the same time, ‘Unmothering’ introduces a tension. It questions actions that fall outside what is considered a female role, almost seeming like an act of leaving or letting go. For me, it raises the question of whether women can choose not to nurture what they have created.

This framework resonates with my own practice, which often focuses on the lived realities of the working class. Nowadays, women are expected to live both within and beyond their assigned roles. As workers, women are not only expected to produce labour but also to continuously nurture their working lives (and often the lives of others as well), as if it were their nature to do so. Mothering/Unmothering aligns with my interest in examining how minimally we are allowed to nurture ourselves, just enough to continue functioning in our roles as workers, while other forms of self-care are gradually taken away due to limited resources and time. When workers are rarely able to negotiate the amount of labour they can endure, and the need for rest is often postponed or denied, the exhibition’s theme resonates with my point of view. It raises an ongoing question for me: how do we decide whether to nurture or unnurture ourselves within systems that demand endless production?

You’ll be bringing The Standard to the Philippines for the first time in January. What excites you most about performing in a new cultural and physical context? Are there aspects of the local space, audience, or environment you are particularly curious to experience?

I think The Standard, which discusses everyday working life under capitalism, repetitive actions such as using computers and software, and attending online meetings, will already feel very familiar to workers in a rapidly growing city like Manila. I think these forms of labour have become part of daily life for many urban workers, whether in Bangkok or Manila.

When the work was previously presented in Bangkok, it generated wide public attention and discussion. I discovered that audiences interpreted the idea of ‘confinement’ in many different ways. The glass box was understood through each viewer’s own experience of limitation at that particular moment. Especially in 2022, in the context of military rule following the coup, the box was interpreted not only as representing the living conditions of workers or state labour policies, but also as symbolising the restriction and erosion of rights under a military government. What excites me most about performing The Standard in the Philippines is how the work may be interpreted differently from its first presentation in Bangkok. As the work remains open to interpretation and discussion, and allows audiences to approach the performance, speak with me, and engage directly, I look forward to exchanging conversations with audiences in the Philippines and to hearing how the box in this work means to them through their lens of social, political, and lived experiences.

In the performance, you create a labourer’s environment with only the bare essentials, including a laptop. What led you to include this object, and how does it help convey the idea of “displaying labour”? How do these material choices shape your experience, and what do you hope audiences notice or feel?

The principle behind selecting the objects inside the box was to include only the essential tools that allow me to continue my everyday work as a creative art director. So, the laptop is not a single symbolic object, but one of several necessities, and behind that, it also has invisible necessities, alongside other invisible requirements such as electricity and Wi-Fi.

What I find interesting is that if the selection were based on ‘what is necessary for human survival,’ almost everything in the box would have been removed, leaving only a bottle of water. This contrast highlights how the objects inside the box are not chosen to sustain life itself, but to sustain work.

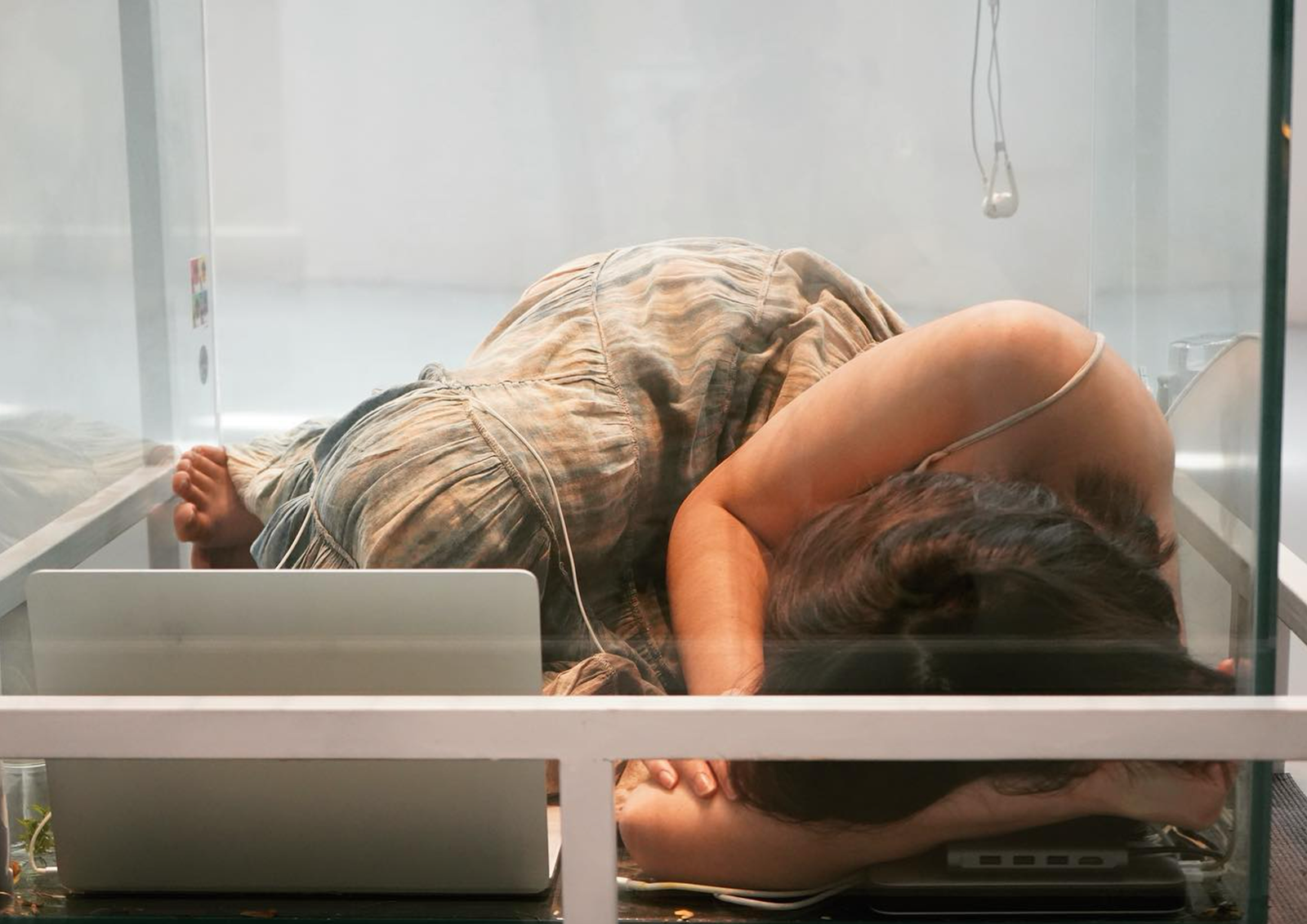

These material choices reflect the nature of my current full-time job, which mirrors the working conditions of many urban office workers today. Their work takes place through a screen that requires little bodily movement, such as typing, touching a trackpad, or small eye movements to track what appears on the screen. (Because of these minimal and repetitive gestures, many audiences even perceived me as a machine or a robot during the performance.) When labour can be performed and work produced through such minimal physical movement, the space required for the body can become extremely small. This resonates with the size of the box, which was designed only to sit in, not to lie down or stand up, as those actions are not necessary for the job.

I think the laptop also reveals a condition in which the worker must remain constantly responsive. Notifications, incoming emails, and digital calendars visible on the screen continuously demand attention and immediate reaction from workers. At the same time, care is redirected towards maintaining the devices, keeping them charged and fully powered, rather than towards caring for one’s own physical or mental well-being.Through this performance, I hope to provoke reflection and conversation among the audience, whether about the reasons for the objects selected for the box or the movements shaped by working conditions. I find it interesting that in The Standard, the performance appears to transport an office worker from a workplace into an art space, inviting audiences to reflect on the current conditions of labour and daily life, and to consider how closely this performance mirrors their own reality.

Durational performance is central to The Standard. How do endurance, repetition, and the passage of time shape both your process and the audience’s experience? Are there moments when the duration itself becomes a kind of language or gesture within the work?

My intention in The Standard is not to present confinement as a condition of being trapped, but to make the process of bodily adaptation visible over time. Building on that, duration plays a crucial role in shaping both my own process and the audience’s perception of the work.

At the beginning of entering the box, I noticed my body exhibiting a sense of unfamiliarity or resistance. As time passed, my body began to adapt, my movements gradually became more natural, as if I had accepted the limitations of space as my normal environment. Over time, it appeared as though I was living inside the box all along, rather than just entering it in the morning.

Through my previous experience of performing this work from Tuesday to Friday, eight hours a day, for a month, I realized that what was more unsettling than the body’s ability to adapt was the human capacity for perception to adjust. At a certain point, I found that I could accept, and even believe, that this restricted, uncomfortable, or almost self-harming environment was normal for me. (I even began to refer to this glass box as ‘my room’, after stepping out of it each day.) In this sense, duration transforms not only my movement, but also my beliefs about what is acceptable within conditions of living and working. For the audience, I think a similar shift occurs. At first, many viewers might experience a sense of discomfort when seeing a human body in such a confined environment. But as they continue to observe over time, the situation can begin to feel increasingly ordinary. Even though they are outside the box, I find it fascinating how their minds will eventually try to make sense of and adapt to this bizarre reality. I have even encountered an audience that described the space as looking comfortable.

In this way, duration itself becomes a language within the work, revealing how endurance and repetition over time can normalize restrictive, uncomfortable, and even violent conditions, particularly when they are justified in the name of work.

Within the Mothering/Unmothering framework, the piece engages with domestic pressures, care, and relational dynamics. How do these themes emerge in the performance, and are there personal or cultural experiences that influence the gestures, rhythms, or pacing of the work?

Within the Mothering/Unmothering framework, The Standard questions the idea of human survival under capitalism, where survival no longer centres the body or mental well-being, but instead requires one to survive as labour, as one must always be able to deliver work continuously.

As a result, each element within the performance does not exist for its own sake, but for work. Care is shifted away from caring for the human body toward prioritizing work above all else. Movement within the performance is task-oriented. This includes the constant need to respond immediately to work requirements, maintain devices so work can continue, monitor batteries, and ensure the system is not disrupted. Care for oneself is reduced to the bare minimum, just enough to remain functional and keep working.

Through this process, other personal needs are gradually taken away, leaving only an awareness of responsibility and duty toward the work itself. The gestures, rhythms, and pacing of the work emerge from these repetitive actions, inspired by my own working experience and ongoing life, when the body moves not according to an instinct for physical or emotional survival anymore, but according to the demands of work and the necessity of sustaining productivity as a labourer.

If the Shoes Fit, 2025. Image courtesy of 李雳绅 Lǐ lì shēn

By being both visible and contained, the performance navigates a delicate tension. How does it feel to inhabit this space, and does it shift how you sense your connection—or disconnection—with the audience?

In some of my performances, I choose not to acknowledge the presence of the audience at all. However, in The Standard, I realized that the glass box itself already performs the function of disconnection. Because of this, I feel the need to respond, to reach out, and to cross this limitation for the audience. For example, I am aware when audiences enter my range of vision. I respond when they wave at me, and I allow conversations to happen.

I believe that my awareness of the audience and my ability to engage in dialogue with them intensifies the strangeness of the situation. Often, the initial conversation begins as a way for viewers to check whether I am truly human. Later, it may shift toward understanding or getting to know each other.

However, the dynamic between the audience and me remains deeply fragile. No matter how long interactions last, the power imbalance remains. Beyond the physical restriction of the small box, I must look up through the bars at the top to speak with the audience. This posture alone reinforces a clear hierarchy between the artist and the viewer. That imbalance becomes even more distinctive when the audience can move the box to any location they choose.

When viewers are allowed to reposition the glass box, whether with good intentions or harmful ones, my body is not only displayed, but also relocated, positioned, and decided for. Leaving the box is not an option. In response to the visibly uncomfortable conditions I have, some viewers attempted to move the box to help me, such as to avoid direct sunlight or to change the view. This contrast shows that while I may appear to control the environment inside the box, the audience controls what happens outside. And both forms of control inevitably affect my body.

For me, the moment that most clearly reveals the difference in power is the act of looking, just me being seen. Viewers can choose to treat me purely as an object, inspecting my body, the objects inside the box, or the screen of my laptop, without engaging in conversation or acknowledging my presence as a human being at all. In this sense, I discovered that being visible makes me feel more disempowered than being contained.

The distance between me and the audience, therefore, is not just physical, nor is it the glass surface between us. It is defined by power, the power to act, to decide, and to control the environment outside the box, while I remain unable to respond or resist from within.

After the performance, what reflections, sensations, or questions do you hope audiences take away? How might the work spark conversations about labour, care, domestic life, or societal expectations?

I hope audiences reflect on and ask themselves questions beyond the visible glass box and the woman working inside. I hope they consider whether there are other “boxes” shaping and limiting their lives, for example, family structures, working environments, or political systems, etc.

From my first experience performing The Standard, one of the strongest realizations for me was how, even in conditions that feel almost unbearable, the human mind is still capable of adapting, finding ways to normalize and become familiar with a new reality. This realization led me to question what else my own mind has already adapted to. Are there other forms of injustice or inequality in society that I have become numb to, simply because I have learned to live with them already?

In The Standard, performing ordinary work tasks in a space outside of the workplace invites audiences to look at labor from a different perspective. I hope it can urge people to think about how capitalism might have shaped our lives, bodies, and the way we live.

At its core, The Standard also challenges how living conditions are defined for citizens from the perspective of those in power, whether governments, corporations, or institutions.

It invites viewers to reflect on how numbers such as minimum wage, working hours, rest time, allowances, or pensions are calculated. Are these numbers designed to support a livable life, or are they simply the lowest possible standards set to maximize profit?

On a broader level, I hope the work encourages audiences to begin asking questions about the standards they might have endured and come to accept as normal, and to imagine whether different ways of living and working might be possible. •