Words and interview Vanini Belarmino

Images Molly Haslund and Vanini Belarmino

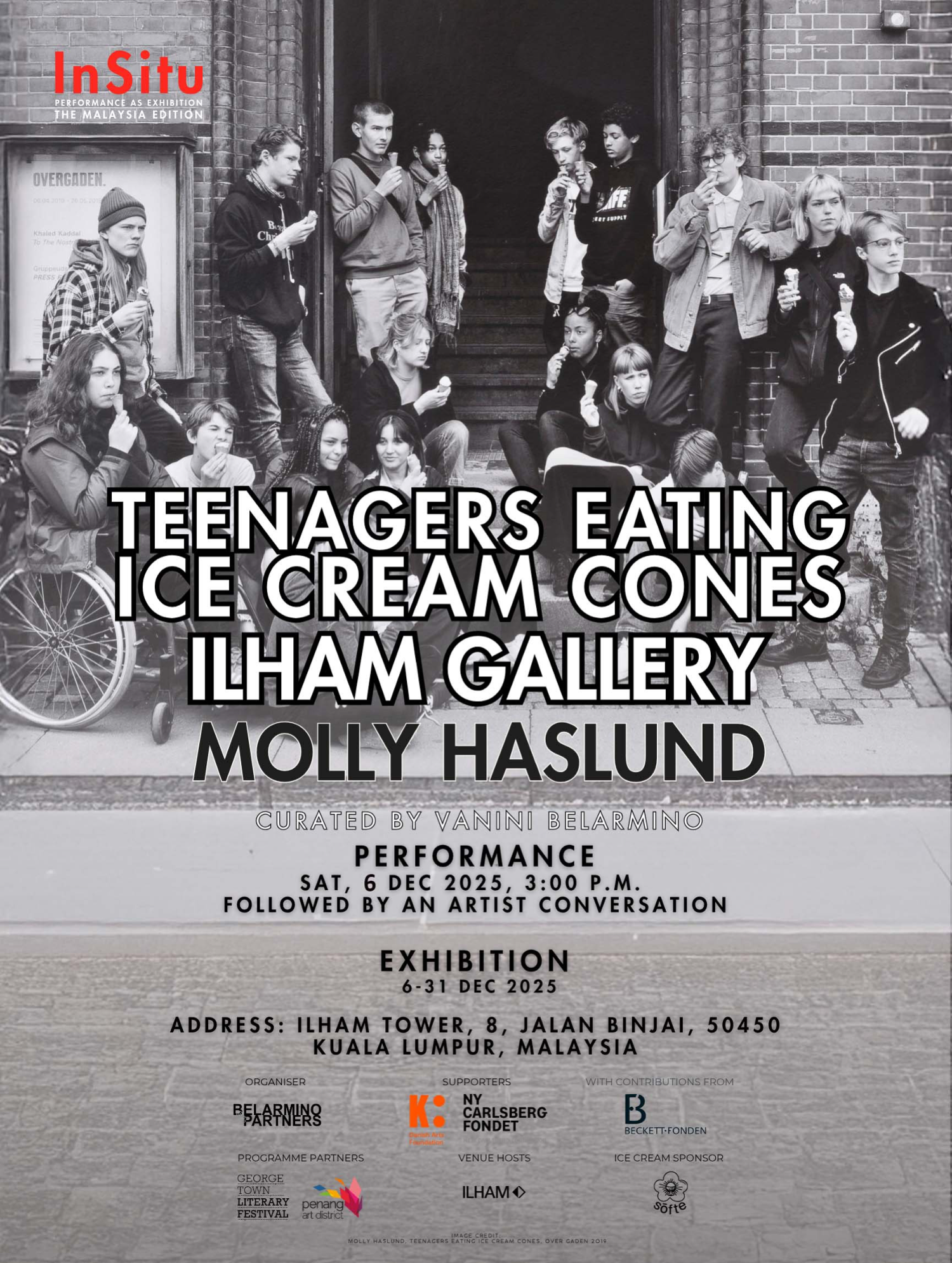

Danish artist Molly Haslund first conceived her work, Teenagers Eating Ice Cream Cones, in 2019 and is now presented as part of In Situ, Performance as Exhibition in Malaysia. The piece unfolds in public space at the threshold between the street and the art institution. In this deceptively simple act of eating ice cream, Haslund reveals a choreography of presence—where the performers’ stillness and the audience’s gaze intersect in a delicate balance between the ordinary and the performative.

For the first time in her practice, Haslund entrusts the performance to others—groups of teenagers whose gestures become a collective portrait of becoming. Accompanied by a pre-documentation photograph displayed within the museum, the work challenges conventional hierarchies of performance and documentation, suggesting that what is ephemeral may also be enduring, and that meaning can emerge in the tension between image, memory, and event.

In Malaysia, Teenagers Eating Ice Cream Cones finds new resonance through its staging at Hin Bus Depot in Penang and Ilham Gallery in Kuala Lumpur. The deliberate choice of these two distinct art institutions—one independent and community-rooted, the other formal and museum-based—introduces an additional layer of inquiry into what an institution might look like, and how audiences engage differently with performance across these contrasting contexts.

As Haslund brings her work beyond Denmark for the first time, she reflects on authorship, repetition, and the quiet potency of shared moments that disappear as swiftly as they are savored—until they melt away.

We’ve spoken before about using public space as an alternative environment for realizing your art, something that began when you returned to Copenhagen from Glasgow. Since then, you’ve created a wide range of works where you are often the performer—either solo or within a collective. What prompted you to create Teenagers Eating Ice Cream Cones, and what led you to give agency to young people as performers in this piece?

Molly Haslund: The idea for Teenagers Eating Ice Cream Cones came to me one day in a public space, when I observed a group of young people eating ice cream cones. It was outside an art institution in Germany. I was standing in a long queue and became absorbed by the scene; by how time seemed to stand still between the teenagers and how the situation conveyed both a remarkable lightness, strength, and seriousness. After a while, it became clear that the ice creams were gradually getting smaller, time was passing, and I knew that it would all end when the ice creams had been eaten. Meanwhile, the teenagers continued, seemingly unaware that they were partly blocking the pavement and the entrance. I had become an observer of a routine scene, and afterwards, the image of the teenagers kept coming back to me. In 2019, I was working on pieces for a solo exhibition and decided to try to reproduce the scene as a performance.

Why teenagers, why ice cream, and why place them at the threshold of a museum entrance? What does this specific constellation of age, action, and site contribute to the work?

Haslund: It came naturally: the ice cream eaters had to be teenagers – just as I had seen them in Germany. It was exciting to pick that age group because it meant that, for the first time, I would not perform in my own work.

There was something quite beautiful, surprising, and perhaps a little provocative about a group of teenagers eating ice cream outside an art institution. They had their backs to the entrance, and that, combined with their ’mastery-of-being-together-completely-concentrated’, and the ice cream cones that united them, made them appear truly strong, almost autonomous against the enormous institution – this impression rendered the art institution, regardless of its organizational structure, a vital part of the whole. I began to view the teenagers as brave, considering the future from their perspective. Suddenly, I saw them as a group of people with a lot on their shoulders, caught in a seemingly totally carefree situation. It also made me think of the time when I and other generations were young – what would we have looked like, how aware were we of the world, and the relatively short ‘melting time’ that the teenage stage perhaps is?

Did you conceive of this work as a singular gesture or as part of an ongoing series? How many times have you realized it, and could you share some of the most striking or unexpected experiences that have emerged in these different iterations?

Haslund: I viewed it as a piece that would be performed repeatedly elsewhere. On September 11th this year, it was performed for the fourth time.

Of course, it’s always exciting to see whether the teenagers actually turn up for both the photo shoot and the performance, and whether the freezer where the ice cream cones are stored is cold enough. And then it comes as a surprise that people stay and watch the teenagers from start to finish – it’s absolutely perfect – but of course, it has been advertised as a performance!

So far, the teenagers have wholeheartedly embraced their role as performers, without hesitation. This was very clear at SMK – the National Gallery of Denmark on 18th October 2020. We did it twice and were in the middle of the second performance. An angry guard, who clearly hadn’t been paying attention at the morning briefing, came out onto the stairs and asked the teens to move. The teens didn’t move. They seemed relaxed and continued to enjoy their ice cream and afternoon together, while the audience remained in place, and others passed the teens on their way up the steps into the museum. In a normal situation, an angry guard and the level of focus involved in observing, and being observed by, a group of strangers would be unusual. But the context predetermined the dualistic relationship between the audience and the performers. The guard did not make them feel unsafe, and it was not long before a museum employee, standing among the audience, stepped forward and explained the situation to the guard, whereupon he burst out laughing. It should be noted that at this time in Denmark, there were restrictions on gatherings due to COVID-19. All the teenagers were therefore cast in small groups and placed in their “bubbles” with those they socialized with daily, which is probably why the guard was especially vigilant.

What do you hope the performers themselves experience while participating? And conversely, what do you want viewers to notice or reflect on when they encounter the work?

Haslund: I hope everyone becomes more aware of what it means to observe and to be observed. It is as if the two groups – the teenagers and the audience – mirror each other and observe each other mutually, but the whole experience also involves how you can manifest something simply by gathering and being present. For the audience, especially, observing becomes a kind of discipline and practice; watching a performance and allowing it to gain value as it develops into something that goes beyond a conceptual framework or an event.

I hope that both teenagers and the audience will enjoy more ice cream together – and contemplate time, transience, and social interaction. The ice cream cones will remain a key element in the work as something that marks its duration. The piece has a very specific time aspect; once the ice cream cones are eaten (not melted), the performance concludes.

The black-and-white pre-documentation of the same teenagers is an integral part of the concept, and the image is displayed inside the museum while the performance unfolds outside. What is the thinking behind this dual presentation, and how do you see the relationship between the photograph and the live performance shaping the audience’s experience?

Haslund: I began structuring the performance piece in 2019. While working on creating a “real” situation, I realized that having a photographer with a large camera present would be disruptive or revealing. So I devised the idea of documenting the performance beforehand, which led to the “pre-documentation photograph”. I am fascinated by how performances were documented in the 1960s and 1970s, often with a single black-and-white photograph.

Choosing black-and-white and only one photo is an exploration of how one can simply capture and present ephemeral media in an exhibition context. The photograph is staged before the performance and already hangs in the museum when the piece is performed, creating a dynamic flow between the two parts of the work. The formal structure of the work is the performance itself, as well as the pre-documentation photograph. The ‘substructure’ exists between the narrative, spatial, and bodily elements that emerge throughout the artwork, from the pre-documentation photograph to the actual performance.

Each time the work is recreated, the photograph is taken in collaboration with a new photographer, allowing the work to evolve and the pre-documentation photographs to vary. Of course, many iPhone photos are taken during the performance, and I have no intention of stopping that, as I enjoy collecting documentation from the live event itself… that is part of it. Out on the street, everyone takes photos of everything all the time. Most performances, therefore, never truly end, as they continue their life as posts in cyberspace.

Beyond the image of teenagers eating ice cream, what have you observed in terms of audience responses? How do you feel the work has been received by peers—artists, curators, museum directors, or critics?

Haslund: In the performance setting, reactions have ranged from irritation caused by the blockade to laughter, surprise, and questions about where to buy ice cream cones. Some visitors to the art institution or museum only realize they experienced a performance when they come across the photograph inside the exhibition and recall passing teenagers eating ice cream at the entrance. This provokes wonder and questions about whether the teenagers in the photograph are the same as they were a long time ago. The institutions where I have exhibited the work have been pleased with the mix of performance and photography, as it combines a live element with an image that can be displayed on the wall. It has also brought joy to everyone to see the teenagers running around the museum after the performances.

I have been criticized for showing the same work repeatedly, but that is the core of it and exactly what I find exciting; the repetition and variation that occur in context, the encounter with new teenagers, with a new photographer, or a new art institution—and how all these elements help to shape the work. My efforts to stage the situation precisely as I saw it in Germany are almost certain to fail, as each recreation introduces more variations, whether in the teenagers’ clothes, hairstyles, or ice cream flavors. However, I believe that the work lies in the fact that I try, that we all try, and it is this space for changeability, the understanding that every moment will be different, that contributes to the work itself.

If you imagine Teenagers Eating Ice Cream Cones being remembered within the broader history of art, how would you like it to be positioned?

Haslund: It’s hard to say, but if it goes really well, I hope it could be remembered as my major work of my mid-career; as a refined, engaging work, using the unique method of taking a situation from the real world and translating it into a performance with very little adaptation.

Looking ahead, what excites you most about the upcoming iterations at Hin Bus Depot in Penang and Ilham Gallery in Kuala Lumpur? What possibilities do these particular contexts open up for the work?

Haslund: I’m excited to see the teenagers’ energy and approach. The two upcoming iterations will be completely different due to the diversity of the art institutions, and also differ significantly from the previous iterations in Denmark. I expect more laughter, more V signs, and, of course, completely new and exciting types of ice cream cones. I also hope the teenagers will ask me lots of questions about what it all means. Perhaps the addition of performances and photographs from Penang and Kuala Lumpur will lead to the overall body of work beginning to tell us something about the differences and similarities of being teenagers in different parts of the world? – It’s hard to predict, but regardless, it’s very exciting to get to show the work outside Denmark for the first time.

Thank you for the invitation, Malaysia! •

In Situ, Performance as Exhibition—Malaysia edition is happening from November 22 to December 31, 2025 in Penang and Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Follow Belarmino & Partners on Instagram for more details.