Introduction and Edits Judith Torres

Catalog text Moreen T. Austria

Charlie Co paintings photographed by Aeson Baldevia

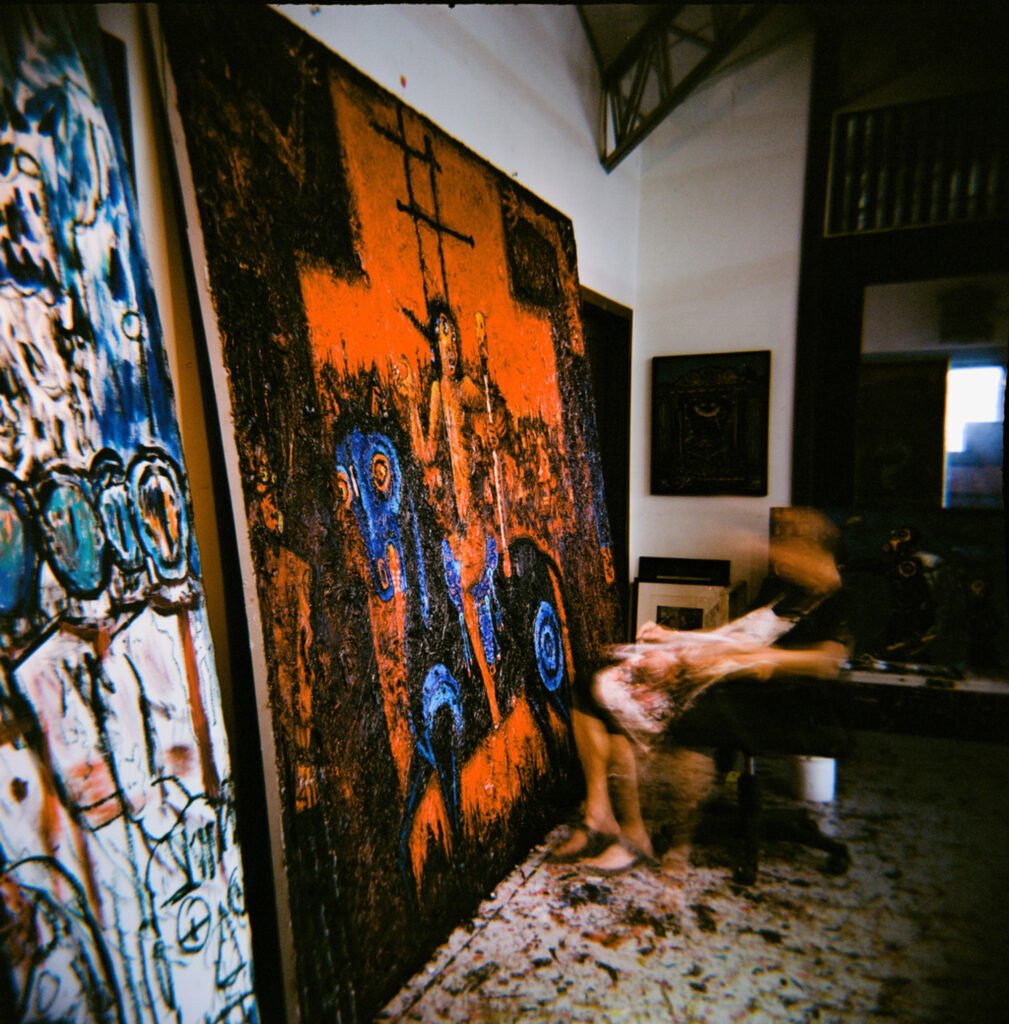

Charlie Co at his studio, working on Do We Have a Choice? Photographed by E.S. L Chen

System Corrupted, Charlie Co says, represents forty years of interpreting the world through art. “The journey has been very, very interesting—emotionally, physically, mentally, it’s all there. I’ve always wanted to create works that hopefully people will reflect on. Artists, painters, we are going to be outlived by our work, so the work itself must stand on its own and speak to the audience.”

Each piece in Charlie Co’s first-solo exhibition of 2023 speaks indeed, as never before. Since he began painting in the 1980s, Co’s work was recognizable for being vivid and visceral. But the masterpieces hanging on Finale File Art’s dusky blue walls are implausibly more so. His canvases have always been awash with passion and a sense of immediacy, now they are slathered with emotions elemental, acute, and urgent; they hit deep and cannot be ignored.

Charlie in his studio, slapping molding clay onto canvas, video taken by Ann Co

In describing Co’s work, the late great art history professor and critic Reuben Ramas Cañete called Charlie Co “a troubadour of the times, a painterly spokesman of the evils and follies that humanity inflicts upon ourselves.” Cañete drew connections between Co’s fantastic, sometimes nightmarish landscapes with Co’s many brushes with death.

Co was a diabetic, whose condition was so far advanced that it damaged his kidneys, necessitating a transplant in 2013. But just before he could have his transplant, Co suffered a bout of gastroenteritis and while in the hospital, developed pneumonia. As if that were not enough, the doctors discovered Co had two blocked arteries requiring an angioplasty and a five-month wait for him to be strong enough to survive the kidney transplant. Co and his wife, Ann, lived in a condo unit next to the hospital so he could have his weekly dialysis during the wait. While waiting, Co painted fervid images of suffering, “his reflections of the social inequities and chaotic politics” of his day. It was no wonder then, Cañete mused, that Co, “a determined bettor on life-and-death issues” worked with intensity and unleashed work evoking sensations of a “tremulous undertow and portents of catastrophe.”

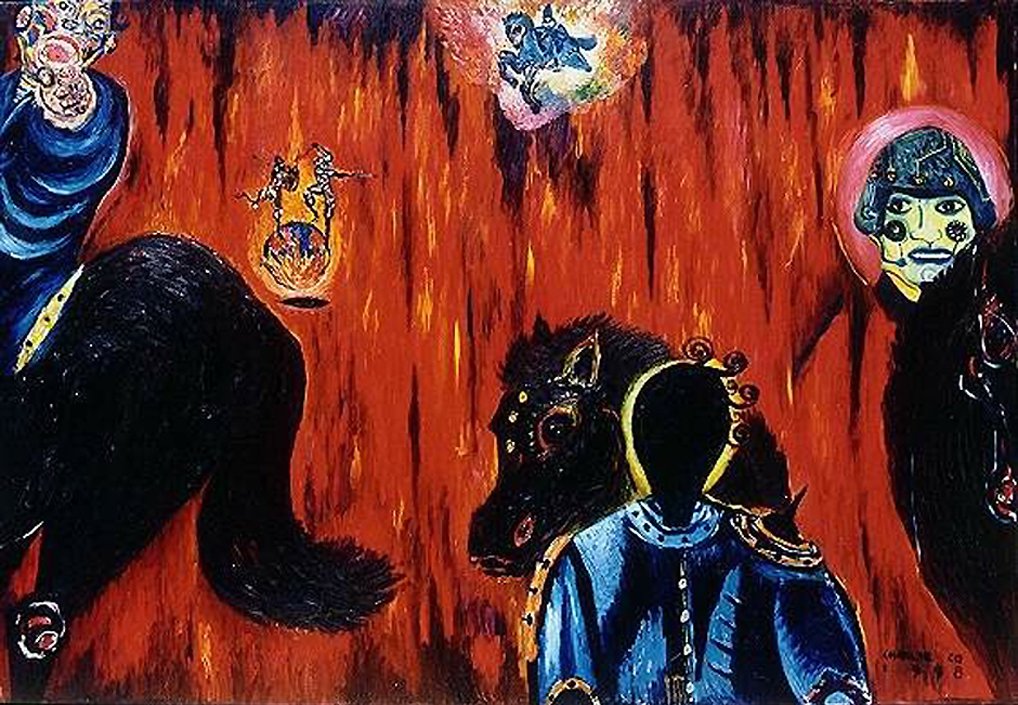

Charlie Co’s earlier works: War Mongers, 1998; Faith, 1999

Come 2020 and the catastrophes that Co’s paintings have presaged for decades are no longer feared unknowns. We have been living them the past three years—COVID 19, social alienation, the rise of neo-racism, xenophobia, online hate and bullying, alternative facts, the Philippines’ deadly war against drugs and degradation of democratic institutions, Russia’s war on Ukraine; the list goes on.

“The world is so fragile. The world is so very fragile,” Co intones as we turn from The World Gone Mad to Paradox. “Sometimes I think it could all go up in flames. But I haven’t lost hope. I haven’t.”

(Editor’s Note: The following texts are excerpts from System Corrupted’s catalogue, written by Moreen T. Austria, interspersed with clips of an interview with Charlie Co by Judith Torres.)

Premonition and the pandemic

On a trip to Australia in 2019, Charlie Co came across Berlinde de Bruyekere’s We Are All Flesh (2012). The sculpture of two horses’ carcasses hanging by a winch shocked and disturbed Co. De Bruyckere often employs the horse as a symbol for humanity in her work. But the method of abstracting the two corpses growing into each other was primal and lay bare the vulnerability of being human. A few months later, the brutal image birthed Co’s Reflecting De Bruyckere (2019).

Here he confronts the fragility of existence and freedom, of life and death. Setting the image of his conjoined horses on a chopping board against a backdrop of eternal burning, Reflecting De Bruyckere conveys Co’s foreboding of death and a war about to come. Painting with scratch-like motions, the red gashes depict humanity’s struggle for life and freedom. A few months later, a virus unprecedented in his lifetime upended the world and claimed millions of lives.

Judith Torres’ interview with Charlie Co

COVID-19 tested humanity to its core. The imposition of multiple lockdowns and his constant thirst for new information, glued Co to the television. The inexhaustible news soon exhausted him and ceased making sense. He says it was like falling into a vortex, the world crushing down on him. He could only turn to his closest reality, his art.

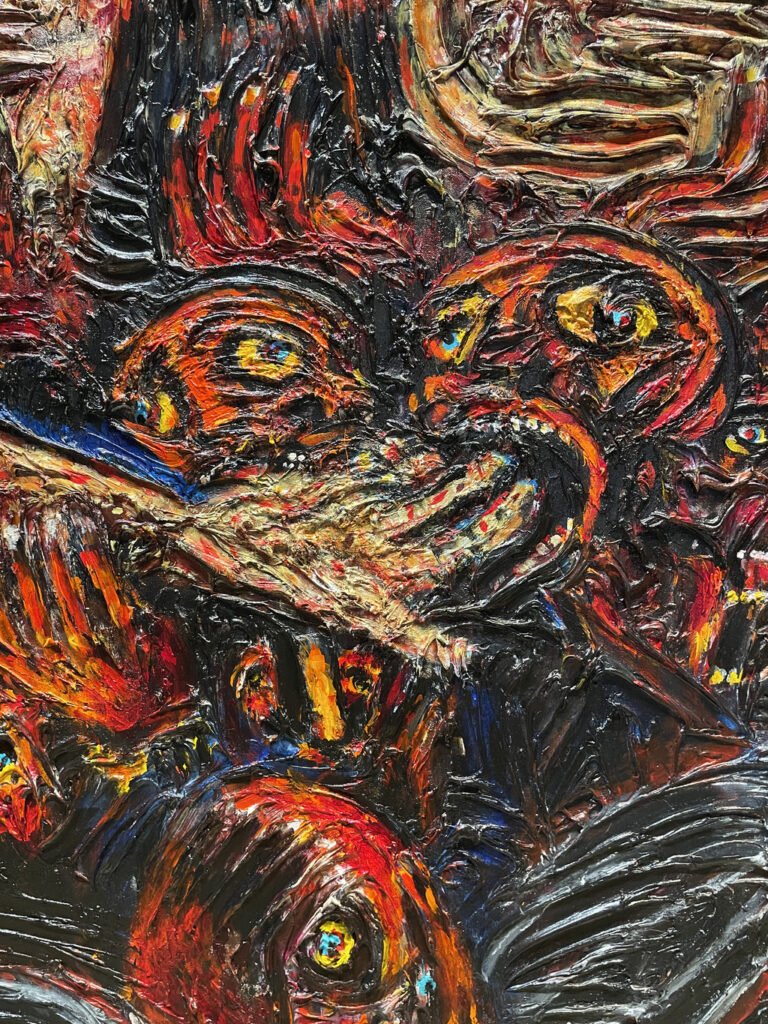

The German philosopher Ernst Cassirer proposed that human beings create meaning and impose order on the chaos of experience through symbolic forms. The World Gone Mad (2020) is encrusted with these symbolic forms from narratives within narratives charged with the artist’s energy, manifested in its formidable size of eight by twenty feet.

In red, black, and orange, the chronicler fills the 160-square-foot canvas with his icons: horses, dogs, birds, and screaming faces, among others, in total disregard for negative space, contradicting the social distancing imposed by the pandemic’s safety protocols.

Details of World Gone Mad: the coronavirus, COVID 19; Charlie with a blue tongue

Six months in the making, the stretch of Co’s monumental work accounts for the pandemic crisis as an epic social and moral collapse. He places himself among his iconography as the man with the blue tongue gasping for air while recounting horrific, galling, and disconcerting stories—George Floyd pleading for his life; the shutdown of ABS-CBN; and the rise of robot killer dogs.

The pale canines on the canvas hark to a time shortly before Co’s kidney transplant in 2014, when he traveled to Tagaytay for cleansing but ended up falling ill. In his fevered state, he heard dogs howling, which he construed as Death at hand. At the height of the pandemic, Co caught the virus and Death felt closer than ever. “We can never escape death,” says Co. When he recovered from COVID, his soul felt a sense of triumph; when the work was completed, a satisfying sense of fruition and completion.

In a video produced by Orange Project, a gallery and art hub in Bacolod, Philippines, founded by Charlie Co, he recounts the making of The World Gone Mad, and the local and world events captured in the 8 x 20-foot painting.

The Cross and The Faith in Question

Religion is a recurrent theme in Co’s paintings. The eternal battle between good and evil, Christ’s crucifixion, St. Michael the Archangel, and depictions of carrozas (horse-drawn floats in Roman Catholic processions), have appeared on canvas as multifaceted subjects in multiple contexts. They recall the prusisyon during the Holy Weeks of his childhood, where cavalcades of life-size images of santos (saints) depicting the passion of Christ in full “pageantry and each carroza provided a stage for the beautiful santos with blond hair.” These stages provided inception for many an oeuvre—powerful, playful, and sometimes whimsical.

But in Santo Entiero (2019), which means “holy burial,” the stage is grim. Like the processions in Silay City, the hometown of Co’s wife, Ann, where a life-size sculpture of Christ is encased in glass and carried on the shoulders of prominent men and politicians, the artist depicts himself as the body carried by a mob of red faces with yellow eyes in business suits. The body, still living but too exhausted to struggle, surrenders to misery. The clouds with horses’ heads impose themselves in the fray. “Everybody wants a piece of you. Evil is everywhere.” He compares the blackness that separates the clouds from the mob to the abyss of doom.

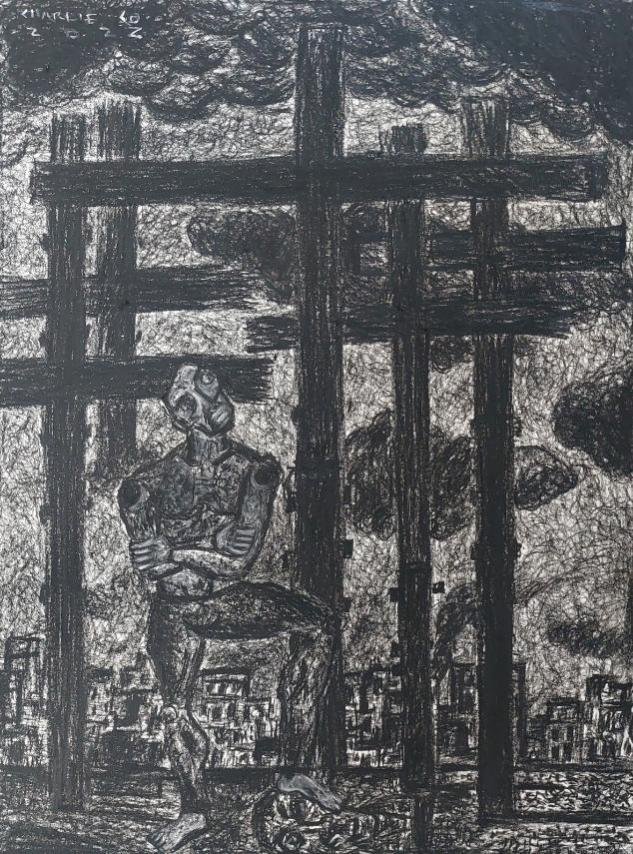

In the Catholic faith, no symbol surpasses the power of crucifix in portraying Christ’s passion. Very personal to the artist, The Cross Series (2022) are black and white “sincere, candid, and surreal,” narratives of his old conviction that the cross and making the sign of the cross is protection. While he was ill, a cross was always at the foot of Co’s hospital bed.

But unearthed scandals in the Church, the otherism and hatred spewed by extremist Christian and Catholic sects, science, conspiracy theories, and new technologies forge compelling questions and a disquieting sense of faith under attack.

The burden of these disquieting uncertainties necessitate expression on a medium more capacious than typical 18 x 24 or 24 x 36-inch canvas. “Big questions, big stories, and big issues should be painted on big canvases,” says Co.

Do We Have a Choice? (2022) is the culmination of this series. In this oeuvre, Co presents multiple crosses with two figures crucified in the foreground. Set against an apocalyptic red city burnt to the ground, the naked and exposed crusader mounts his formidable black battle horse carrying a mighty double-ended matchstick. One end holds a face, the other unlit, like its bearer with two faces. He raises his free hand as if asking: What did we do to the world? Do we want this? Do we still burn what has been burnt?

As with The World Gone Mad and other works in this exhibition, one could get drawn inside the chaos and energy of this oeuvre. Co says this was the first time he used modeling paste in his paintings—gallons and gallons of it. The process excited him. The physical nature of splattering the material on the canvas, sometimes hurling a mass of paste at full strength, and the sounds that came with each action were empowering and therapeutic.

Questioning the Systems

But the questions never stop. And always the visionary, Co burdens himself with the biggest ones. In search of answers and immersed in the daily news, Co’s themes in System Corrupted span local, national, and global concerns—all highly political. But because they are drawn from experience and parallel events in his life and mediated and interpreted by his consciousness as a human being and artist, the works will always be personal.

The 2022 Philippines national elections generate inquiry and evaluation of the country’s recurring system failures. The First One Hundred Days (2022), a work in two parts, depicts the politician in his first hundred days in office and thereafter. His hand on a Bible and other raised in solemn oath, Part One is predominantly red. His eyes menacing and blue suggest that the politician is more humanoid than human.

First One Hundred Days I and II, acrylic on canvas, 4 x 6 feet, 2022

In Part Two, Co reveals what hides behind the promise: the politician is two-faced. Leviathans surround him, some obvious, others hidden; he soon gets sucked into the corrupted system. His horse face for a body is greed.

Charlie Co starting work on Paradox, November 11, 2022, video by Ann Co

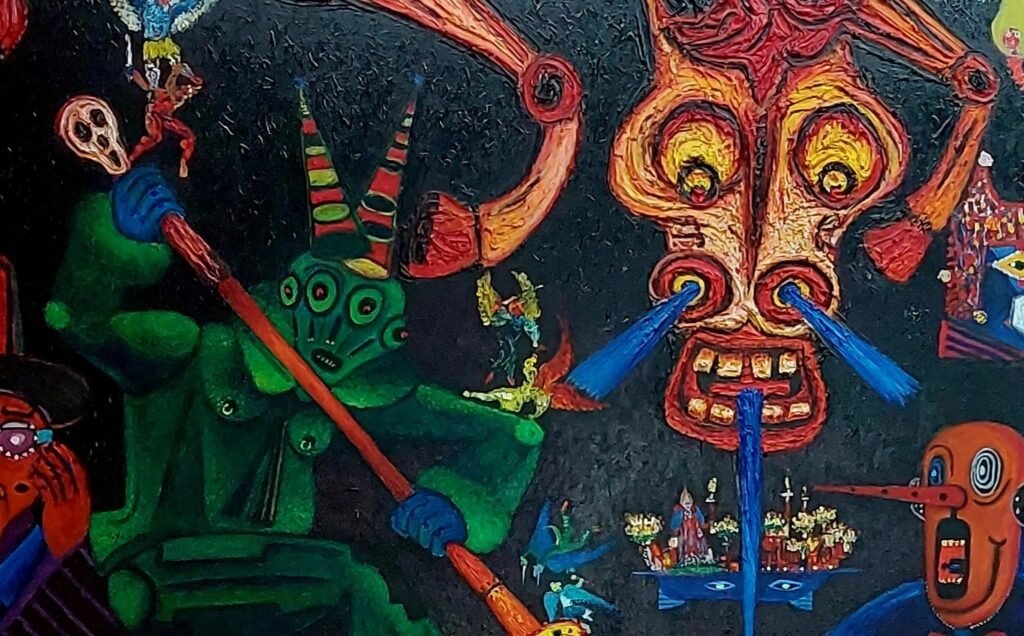

“The art world is made up of institutions and communities;” multiple players each have their internal politics. Living and breathing in the art sphere for forty years, Co examines his role in the system: Am I really a part of this so-called system? Have I been corrupted by this system? Why do I have collectors? I paint war and chaos, yet they buy my art—why? He asks all these questions and expresses disquietude in Paradox (2023).

Wary and darkly whimsical, replete with familiar and unorthodox symbolism, Co situates himself at the focal point of the composition—the winged man holding paintbrushes with paintings behind him.

The wings are a symbolic shield against evil, a representation he previously employed in his St. Michael’s Visitor (1997). In this work, the wings are golden yellow, perhaps a more robust protection against the fiery horse that wants to devour the artist’s soul, its blue sword tongue ready to stab Co on the head; and against the evil green figure thrusting a dollar-edged spear at Co’s neck. The faceless figures in white with orange ties donning yellow bowler hats stand for the players in the art world. Behind the players stand much larger entities. Some blatantly reveal themselves, others inconspicuous. The chandeliers represent affluence and its corruptive influence on the art world. Paradox asks the artist’s biggest question: Inside this world, how do I protect myself and my art from being devoured and infected by the system?

Detail, Paradox

With his last piece, Co proffers one answer. It lights a path and enables sight of the fragility of existence, the vulnerability of man and the world; an icon that represents these epiphanies and his response: the matchstick. In Finale Art File’s triple-height gallery, Co installs three colossal matchsticks of forged metal. The message: We have three matchsticks. One bears the world. With the stroke of one stick, everything could burn to the ground, the whole system corrupted. •