Interview Patrick Kasingsing

Images Marc Brousse

Hello Marc! What are you currently reading?

Hello Patrick, hope you’re well. At the moment, to inform my next artwork, I am reading a book about the Mourners of Dijon, the sculptures commissioned to surround the tomb of Philip the Bold. I intend to create an illustrative allegory based on that historical masterpiece.

I’ve also been reading Stephan Zweig’s “Letter from an Unknown Woman”. I deeply admire this humanist writer’s capacity to transport you in time with his affective writing and narrative tone. I very much resonate with his pronouncement: “I was sure in my heart from the first of my identity as a citizen of the world.”

Congratulations on winning the 2020 Architecture Drawing Prize for the hand-made category! Can you tell us a bit about your winning entry, ‘Dear Hashima’? Why did you enter this particular artwork into the competition? What did you hope to gain or learn from joining?

Thank you, Patrick, it is an honor and a pleasure to have won such recognition from the Soane Museum and the jury of the TADP. I didn’t expect such recognition.

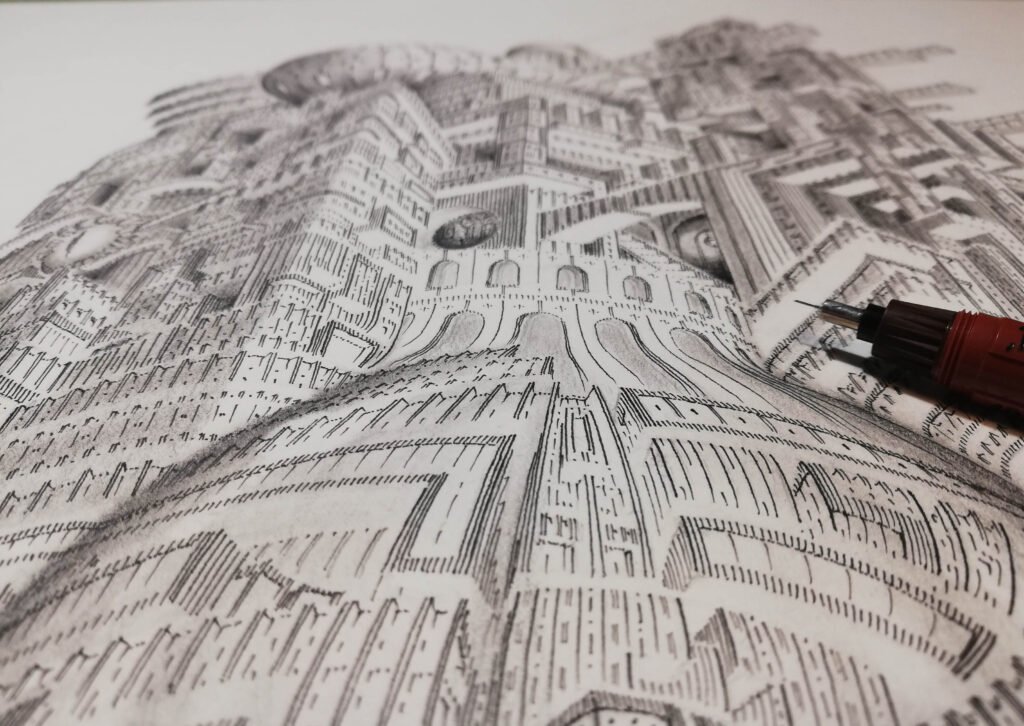

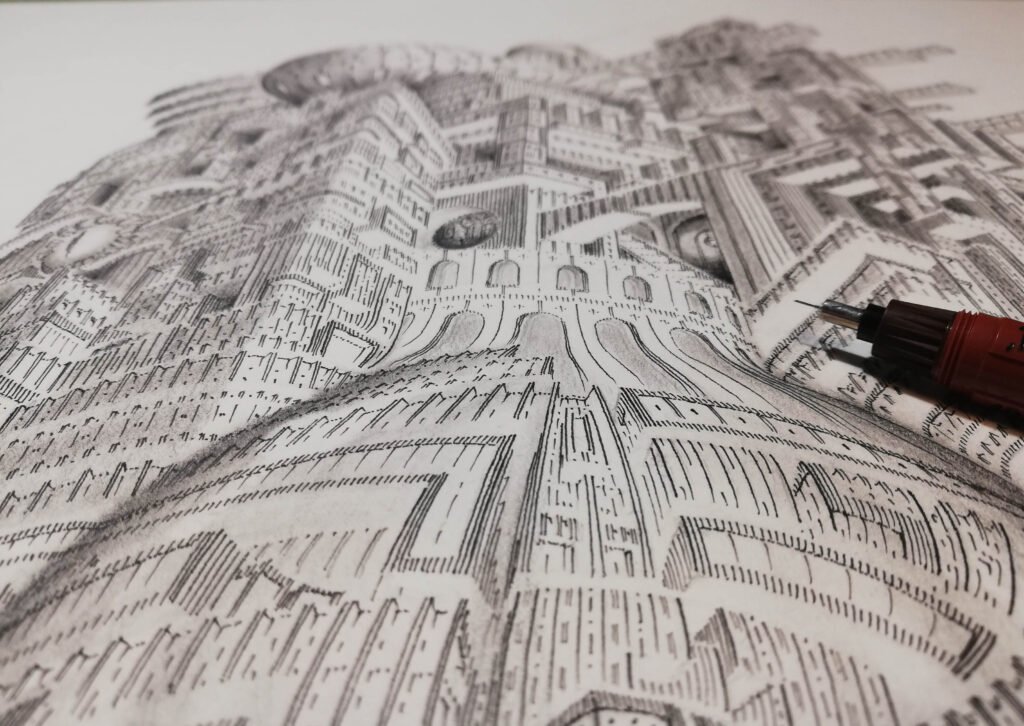

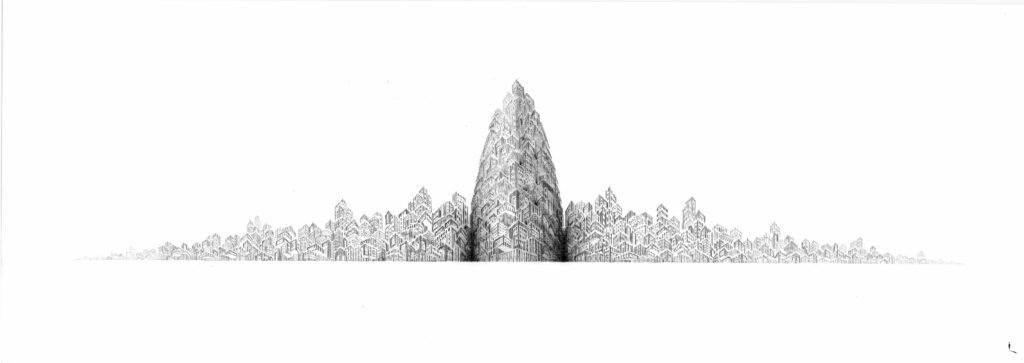

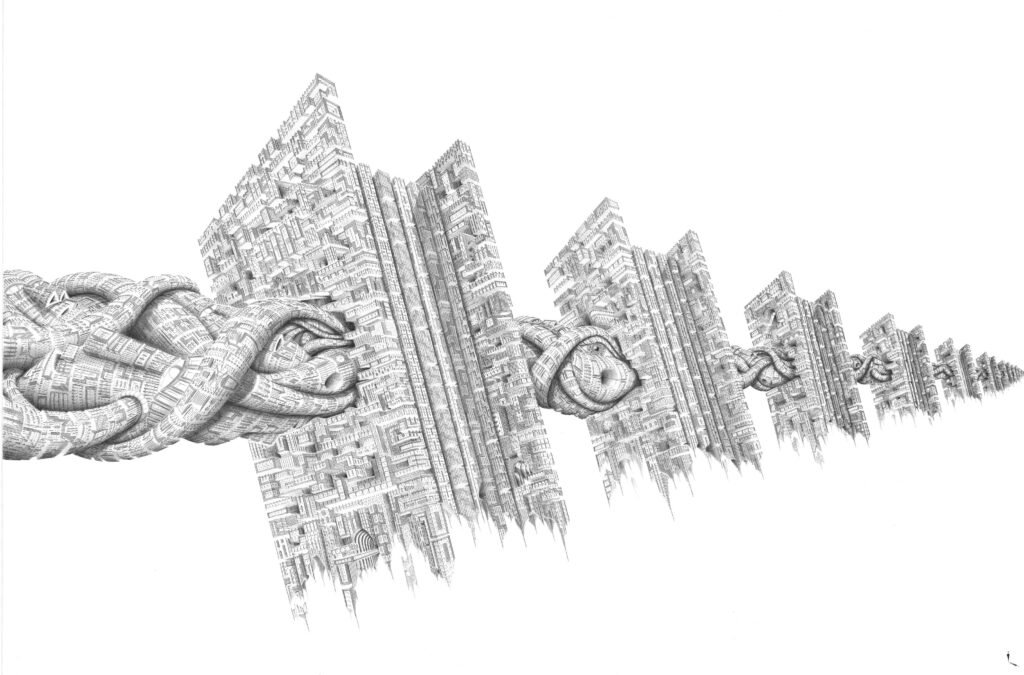

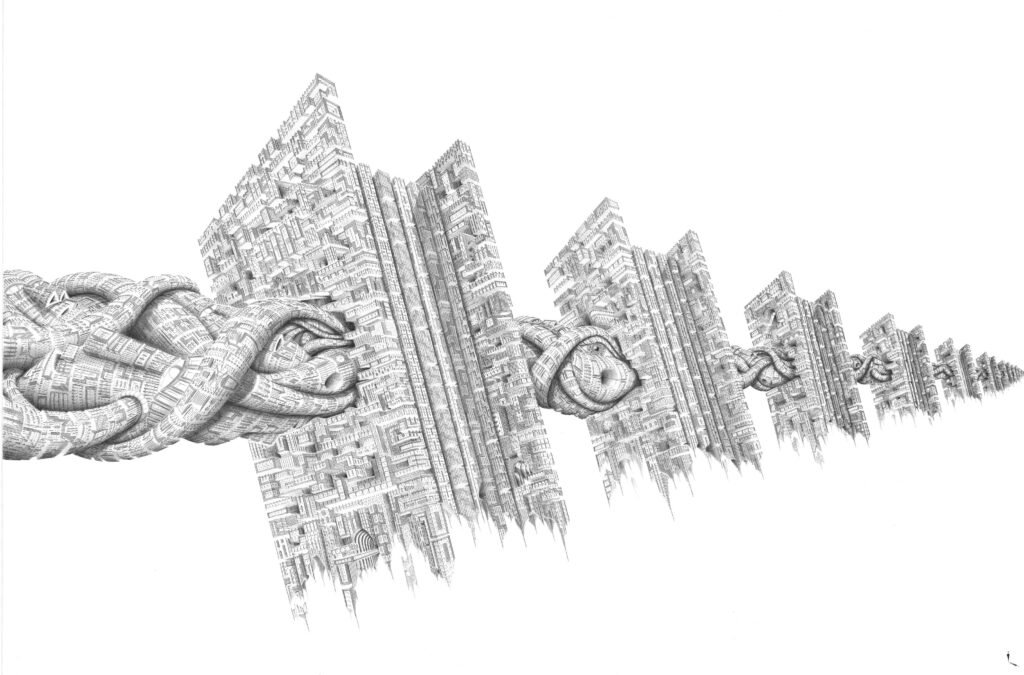

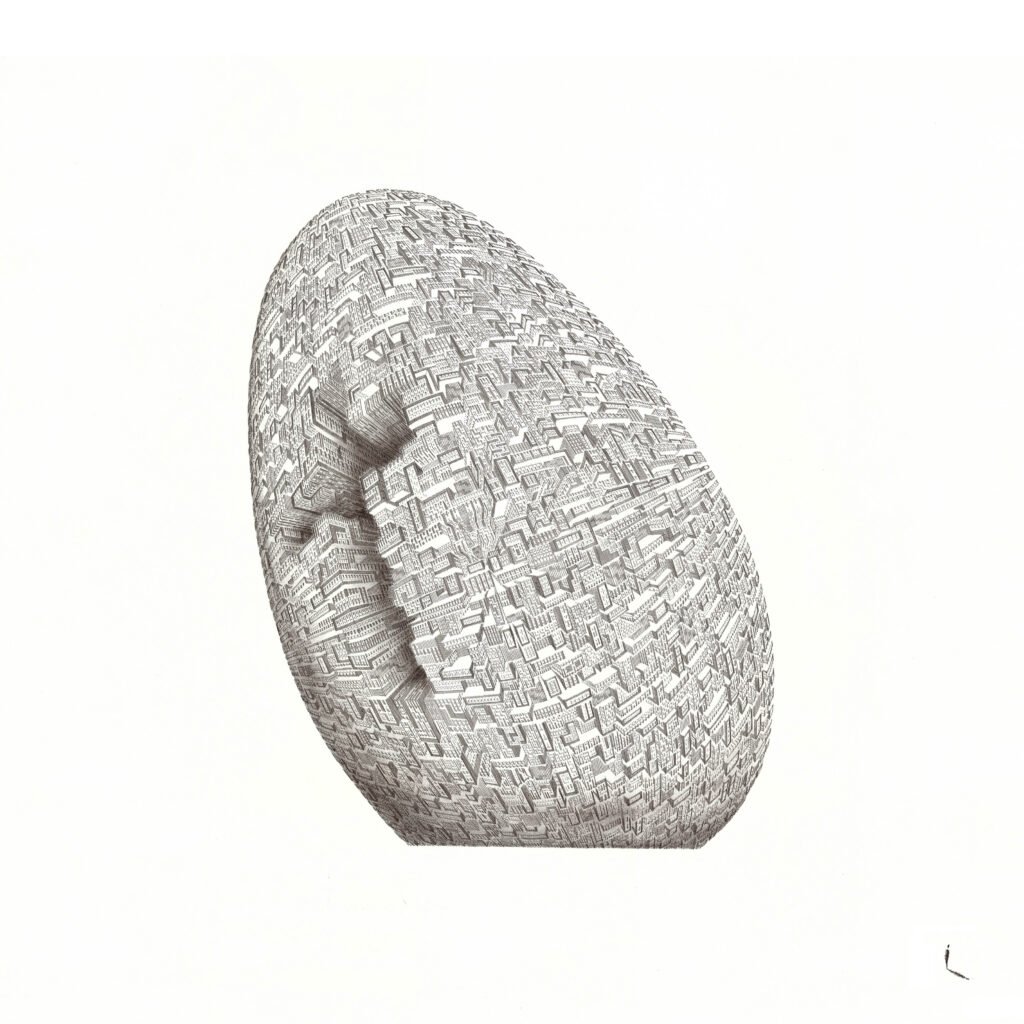

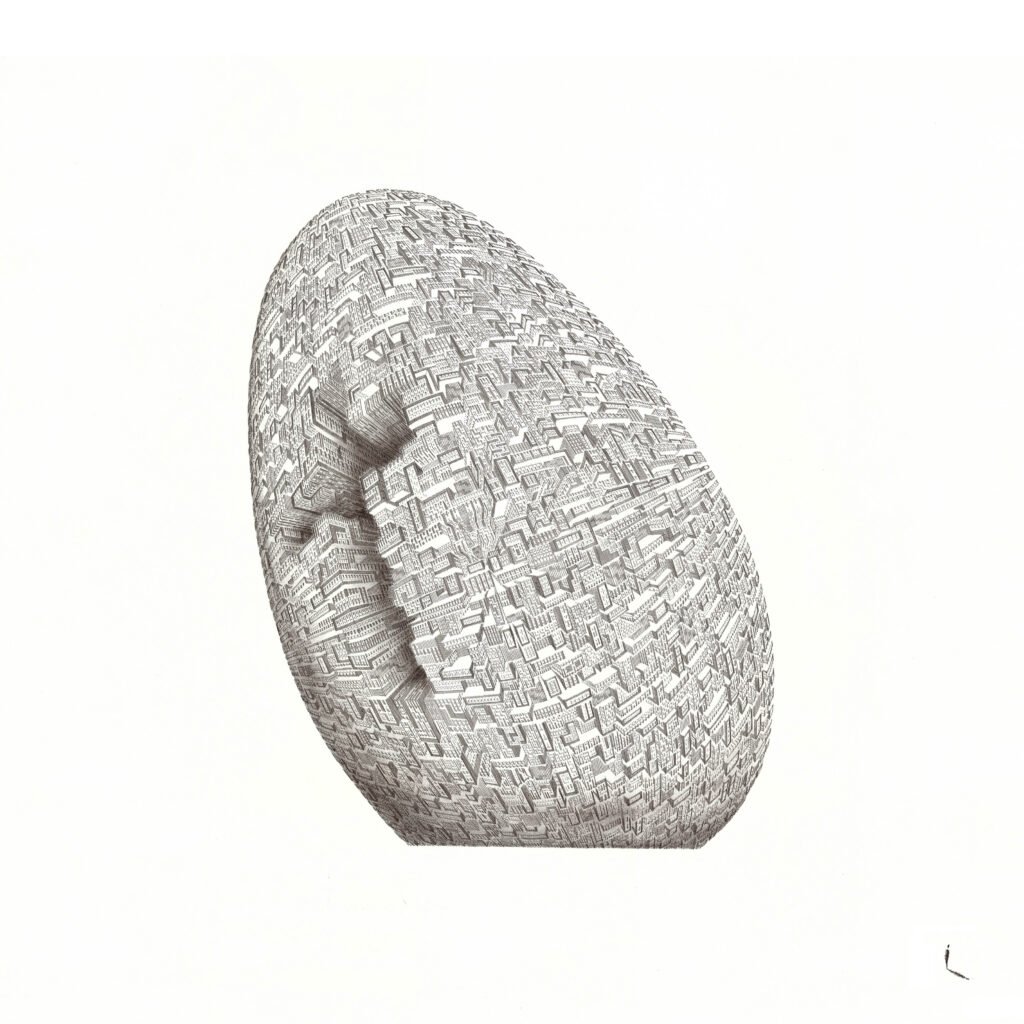

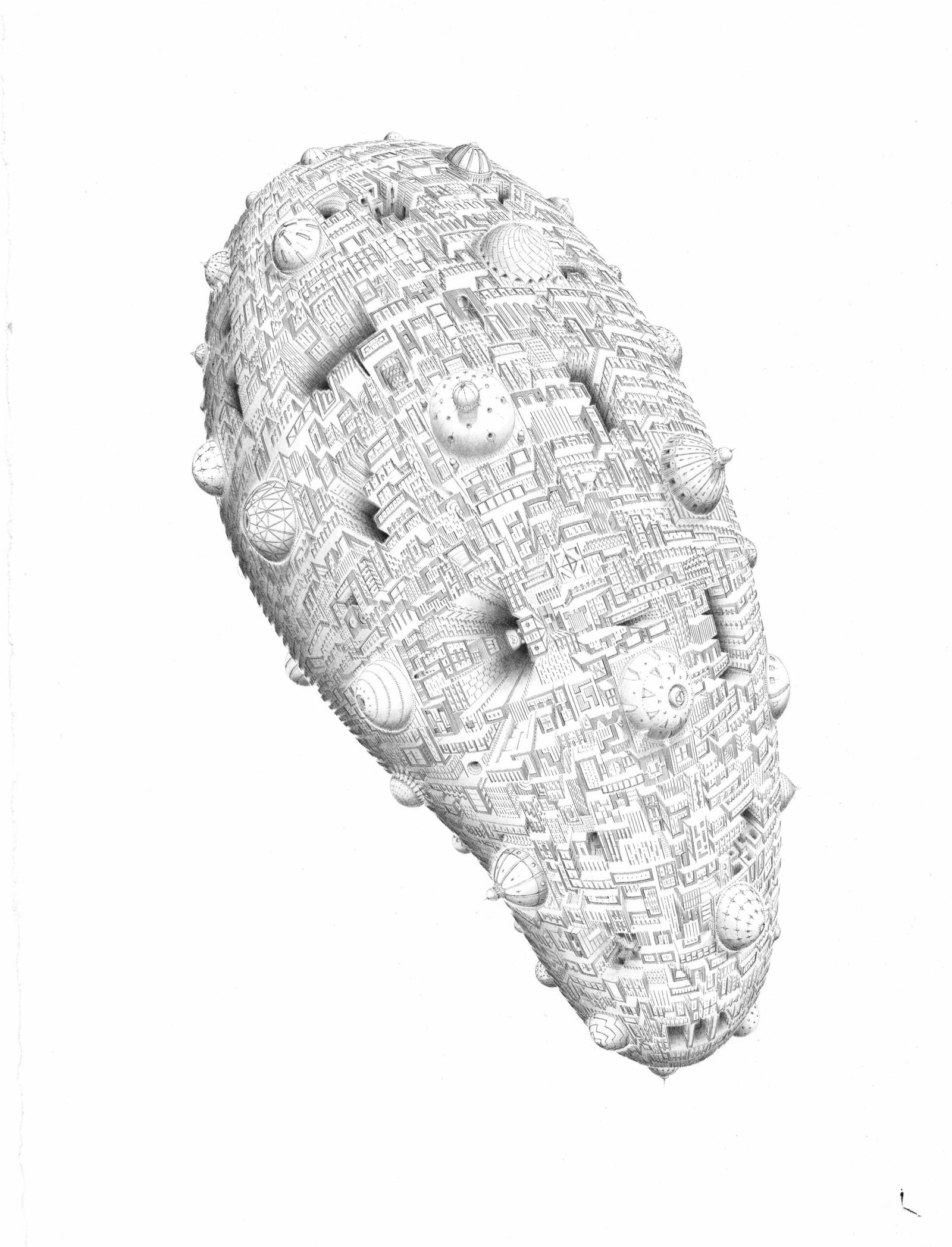

The drawing “Dear Hashima” is taken from a series investigating urban expressions and utopias, and interactions between the ancient world and the future. The drawing uses a technique called ‘traitillism’ and features a second layer of invisible ink which, when exposed to UV light, reveals an illustrated underlayer: the soul of the city.

Depicted in the artwork is the tiny Japanese island of Hashima (commonly called Gunkanjima, meaning ‘Battleship Island’), a long-abandoned coal-mining center, which was at one point in time, the densest city in the world before its closure in 1974.

The artwork expresses the conquest and imposition of the urban grid on what was once natural territory for industrial need and Nature’s eventual reclamation of the space it was robbed of. It is a depiction of the interplay between the artificial and the natural, the organic and the urban. By depicting this ‘dialogue’ between the architecture of man and nature, the artworks question the position and identity of Man within the city and Nature’s expanse. Beyond this forceful imposition on nature, what is it truly that Man wants? This line of thinking brings to mind noted sociologist and philosopher Zygmunt Bauman’s definition of the Contemporary period; a utopia of the hunter who kills until his carnier is full. Man does not rest until perceived threats or sources of discomfort and anxiety are controlled, tamed, and conquered.

Joining competitions for me is another way to share and transmit my ideas and beliefs concerning art and architectural representation. These competitions offer people like me who have something to say about the architectural realm a means to express one’s vision, engaging peers, the jury, and my viewers in discourse with drawing as our medium. After all, drawing is the language of architecture, the primary act that brings structures big and small into being.

The fact I have been awarded comforts my convictions and encourages me to go deeper in this field of expression, utilizing the technique I have developed.

You probably get asked this a lot but for the benefit of our Kanto readers, can you recount to us the beginning of your drawing journey?

Drawing is fact of life for an architect. I have been drawing for a while so let me recount how I nurture the act daily. When my family and I resided in Brussels, my day would start when I bring my son to school (I nicknamed him my little Caravaggio because he was born on the same day as Michelangelo Merisi). Every morning, my son and I would behold fragments of architecture on our walk from home to school, with Brussels, the surrealist city, a willing accomplice. These daily walks allowed my son and I to bond and simultaneously discover the poetics of space and the capacity of architecture to affect and define our memories of the places we live in. These little walks reinvigorated my memory of spaces and triggered my desire for more exploration in a medium other than architecture.

After these treasured walks, I would then proceed to my studio where I start working and sketching. I would start by practicing my hand while listening to the classics, where I let the cadence and rhythm inform my movements on paper. I would then switch to more contemporary sounds, which sometimes trigger the necessary emotions and ideas I need for a a project or a piece; I am really heavily influenced by what I listen to and recognize music as a co-creator. One of my favorite composers, a fixture in the studio, is Max Richter.

When my eyes grow tired and my professiona; discourse with line and surface can go no further, I would do sketches that are much more emotive and intuitive, oftentimes depicting the interweaving of imagination and reality; sometimes, I would step up out to visit an exhibition.

The evening is generally dedicated to my wife and son. It is important for me to make a clear distinction between professional and private time. It is also the time of day dedicated to catching up with friends and family

Sometimes, depending on my mood, I find myself enjoying working at dusk. You feel as if you are surrounded by the shadow of the universe, and the silence and peace trigger a torrent of artistic expression unhindered by daily routines.

You usually work with charcoal and ink, and it is interesting how the behavior of your chosen drawing materials echoes what you wish to communicate about the concept of epigenesis concerning urban spaces; was this intentional on your part? what do you enjoy most about the process of traditional illustration?

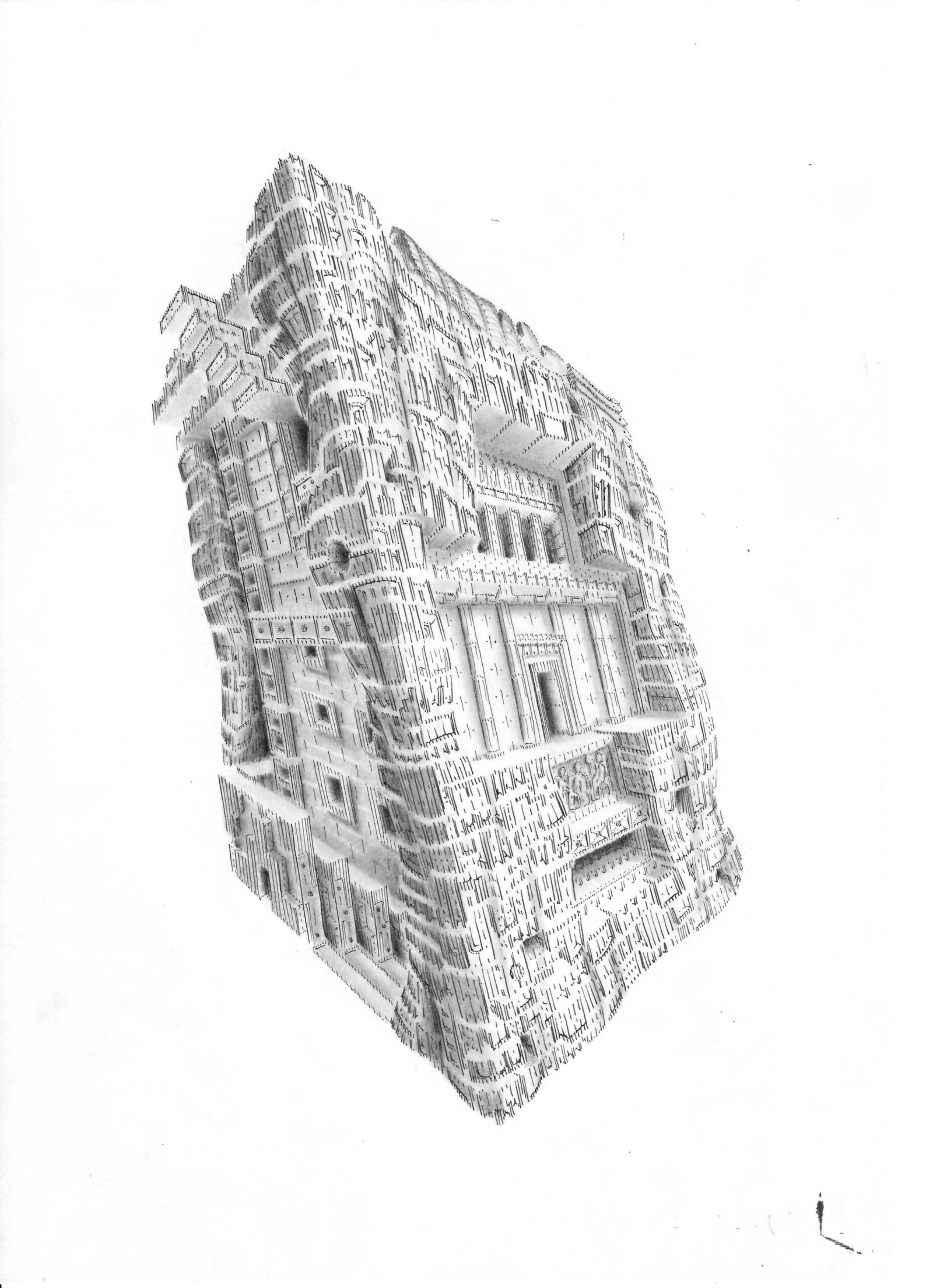

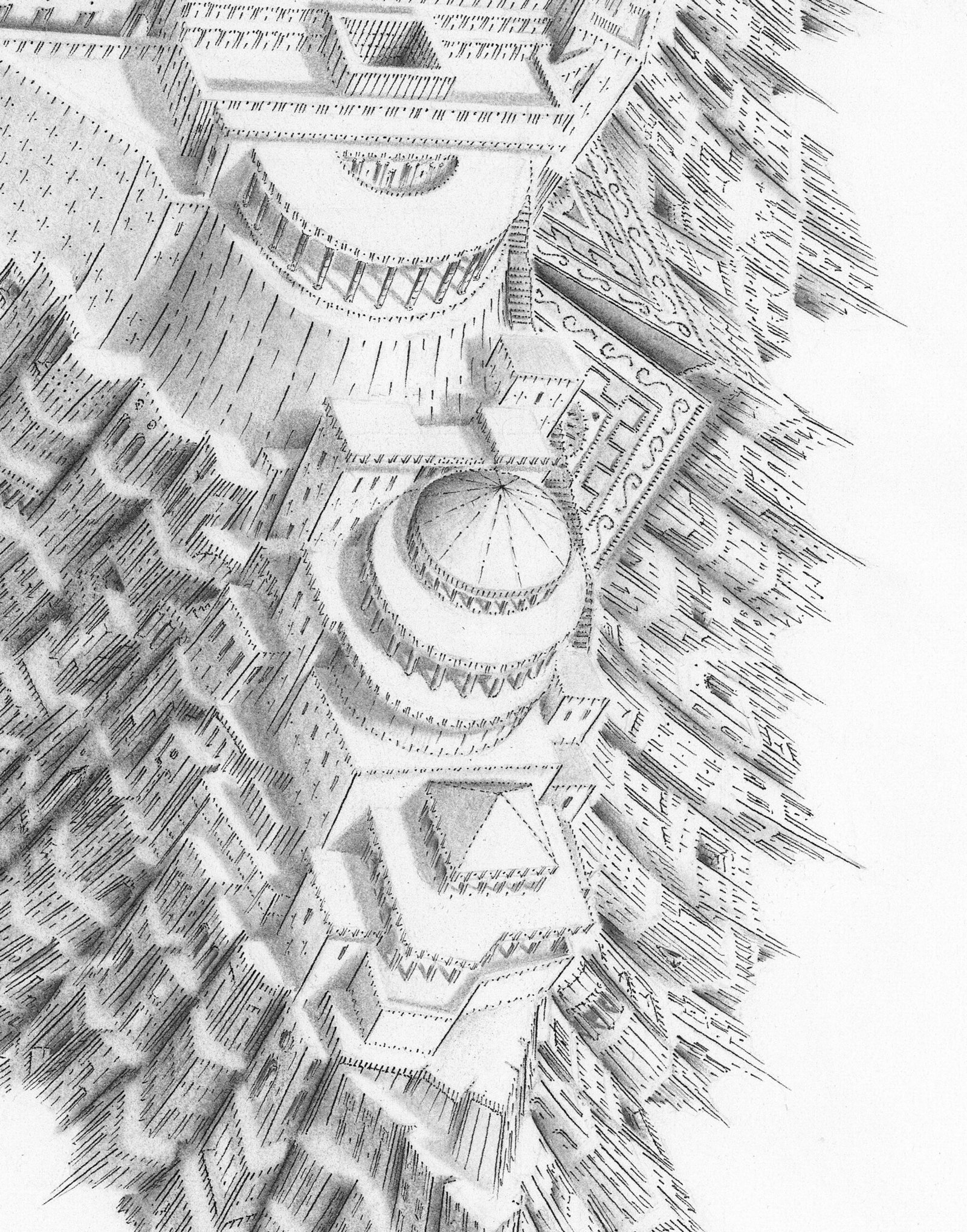

You understand the principle perfectly. The ink establishes the urban grid, the architectural score ( like a music partition), the different global patterns that establish the urban space. The transitory spaces that I draw are both abstract and figurative, permitting me to accentuate the notion of epigenesis, likeness tempered with difference and complexity, while contradiction adds weight to the orderliness.

Every city or urban artifact is a unique species in perpetual evolution, a living organism. The epigenetic principle states that development is the outcome of certain underlying rules plus specific sensitivity to the existing environment; this concept is transferable to urban development. The ‘traitillism’ technique I developed allows me to express this principle.

Overlaying these concepts now in the act of drawing: the sequence of interweaving lines and hatching are both expressions of material, but also of the interplay between line and space, order and chaos, complexity and simplicity, qualities that are inherent in varying degrees in today’s built environments. The charcoal’s solid finish and malleability permits (like the concept of parti and poche), the depiction of structure and volume, fullness and emptiness, the expression of solidity and space through the rendering of light and shadow. Each architectural object can reveal its own identity, vibrating with the energy to extricate itself out of the larger whole. The capacity of charcoal to effortlessly translate feeling and emotion by way of the lightness or tightness of which it is held on to further adds to its being an ideal material

What I relish about the process of traditional drawing is the direct and intimate connection it triggers with your mind, your eye, and the medium. The temporality in the drawing process is also interesting, by the intensification of the lines, you explore the boundary of the object or the space you bring into existence. You translate visions and images and make them ‘true’ when depicted on a surface, and oftentimes, there is a need to devote hours to layer upon layer of articulation and depiction, a fleshing out that is akin to the birth of a living organism.

The seamless distortions and projections in your illustrations showcase your deft drawing skill; from afar the illustrations seem to have been constructed with computational assistance but upon closer inspection, one starts to see the human, man-made aspects of the work; for your illustrations that ruminate on urban spaces especially, what do they say about your observations and understanding of the urban spaces you’ve lived in and have encountered in your journeys?

The connection I feel with my craft and message is much stronger and uninhibited when I draw by hand. While my work might look like an exercise in technicality, it is first and foremost, my impression and personal reading of man and his relationship with urban and natural spaces, and thus the occasional crooked line is a welcome accident.

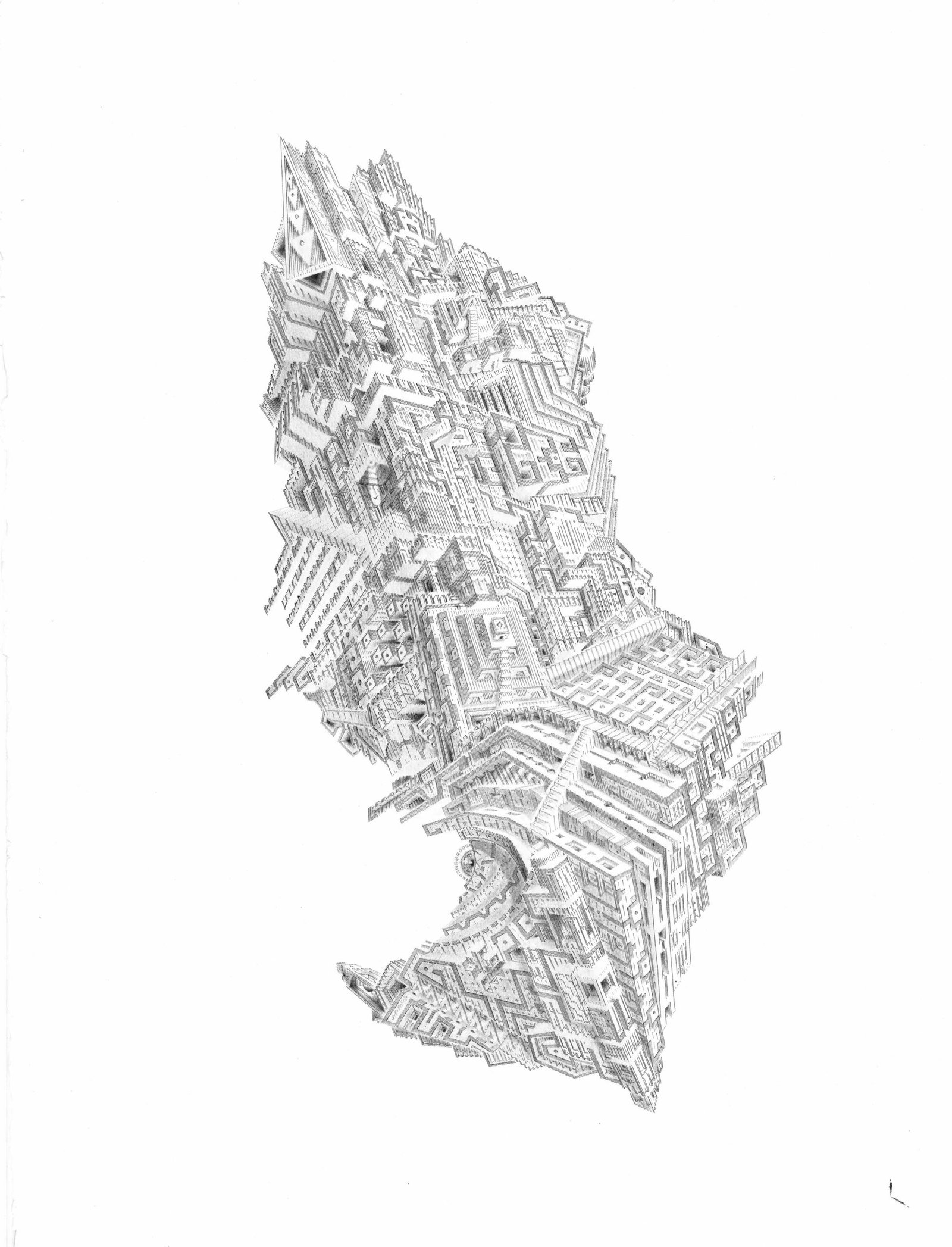

I have the impression that the urban spaces we live in attain an aspect of both harmony and diversity in them, not due to uniformity by which it has been laid out but because the space is a combination of spatial consonances and dissonances that balance each other out and ultimately help the space to work and live.

A real-life example: during my time in Brussels, there is a multitude of façades (as befitting a surrealistic city) representing differing styles via stylistic articulations (ornaments, high, style, openings). However, a sense of contenant or containment unites all these stylistic gestures together, facilitating a dialogue between the façade and its ornaments. Overall, you feel a sublime urban unity despite its diversity, an orderliness emerging out of apparent randomness.

Controversially, we can observe some places (like the Haussmanisation of Paris) that are defined by specific urban rules, a fixed grid, a constrained rhythm, or a specific template, composed and governed by classical treatises and others through a collection of aesthetic interpretation. Because you plug in repetitive measures and strict rules, there is a rigid manipulation of the urban rhythm, sacrificing dissonance and diversity with an aesthetic uniformity and predictability.

The granular energy transfer in an urban space, from the self-assertion of façade ornaments, the steadfast stance of a building’s skeleton, the crisscrossing urban grids…it fascinates me as you get a sense that all this energy expended is in service of a higher ideal, beauty perhaps or some other sublime ideal that is hard to describe.

Would you say that today’s urban spaces could benefit from more ‘humanity’ in how they are designed and plotted out?

I think today’s Architecture is very much divorced with Utopian principles, much too oriented on economical needs, and heavily reliant on technology and ‘smart cities’ in order to solve big urban problems. The solutions being posited are macro, generalized, like some uniform blanket that can be draped over a city. But we are forgetting the value of thinking ‘small’, thinking human-scale, thinking about how such massive changes can affect the mind and the heart; treating urban problems as symptoms of a much larger problem, and allowing different communities space to breathe and contribute to the solution (instead of forcing a solution on them) I feel would lead to more inclusive, diverse and ultimately happier spaces.

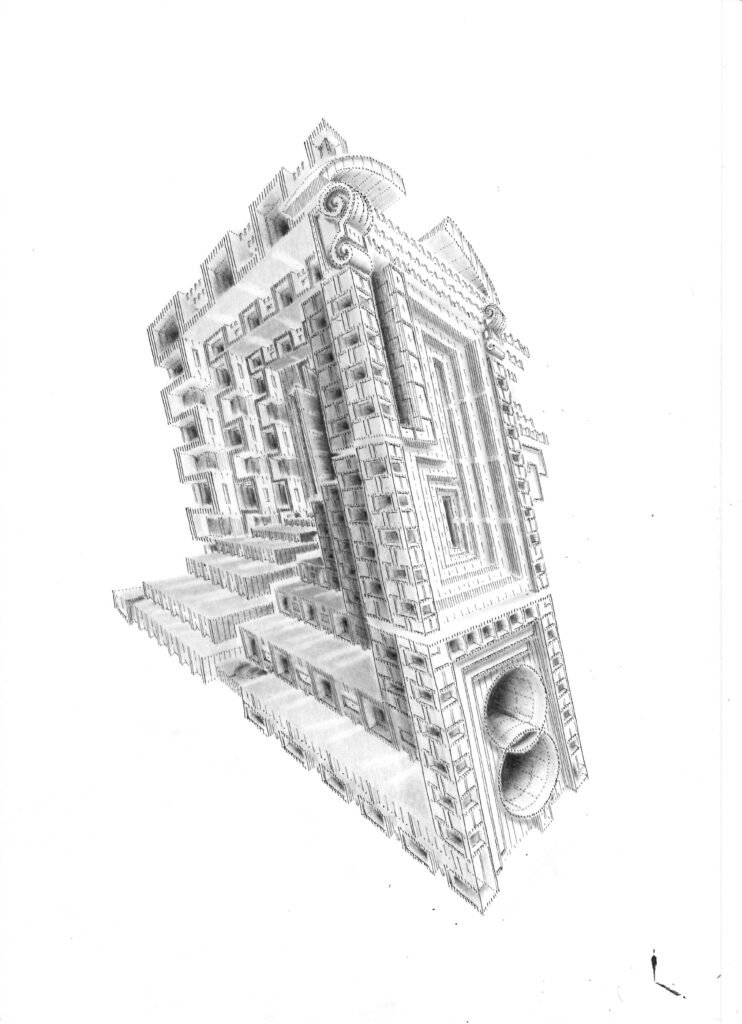

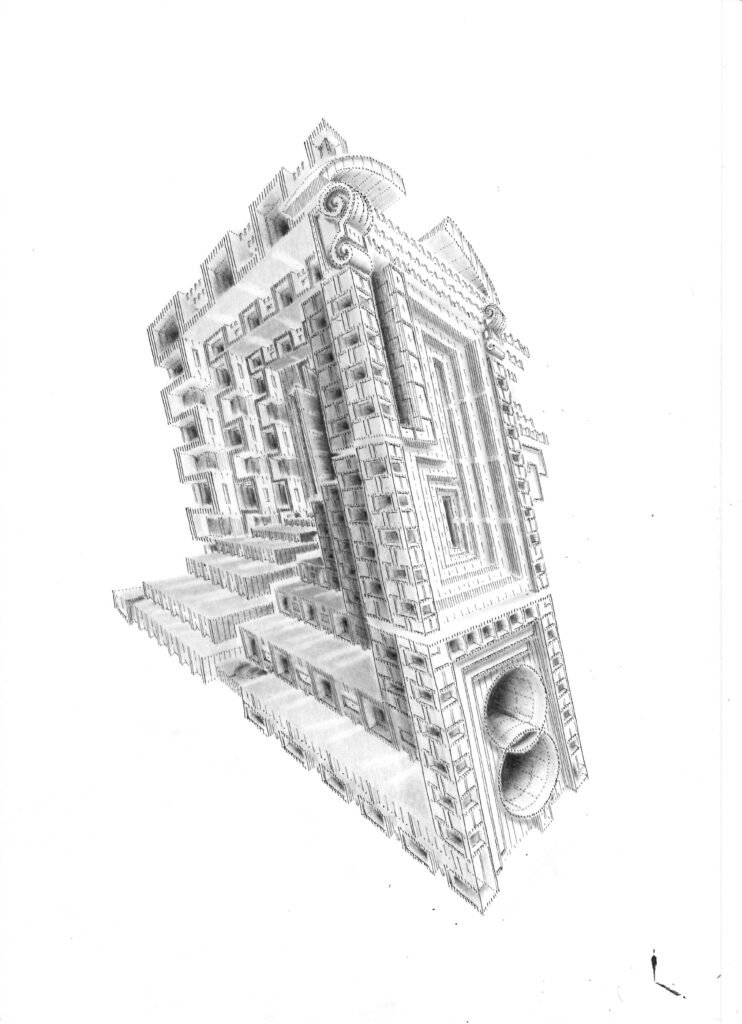

Fragment XIX, 20 x 30 cm, 2019

Andene Signature, 55 x 70 cm

Is your being an architect an inseparable part of your drawing journey and mission?

Architecture in my mind is the ultimate art. It combines all the other realms of artistic expression and contributes directly to their identities and their enlightenment, like how a space receives music or the image of a space captured by the camera.

Art serves as my bridge between the physical world of architecture and my imagination. I like the fact that like architecture, art should appeal directly to the senses. It needs to exert expressive strength, a level of uncertainty and vagueness to allow possibilities and translations, imbued with soul and a voice that can reach out to its viewers. Like architecture, art has the capacity to offer shelter and space for those whom its message resonates with. I cannot imagine separating these two fields I am intimately involved in at all.

Do you foresee yourself evolving this illustration style as you seek to further explore other desired themes and issues?

I will definitely continue to evolve this style (scale drawing, integrating more opinion, color), because first and foremost, I derive enjoyment from doing it. I also want to respond to how people react when they see my artworks, their level of comprehension (not just aesthetical comprehension), and the effectivity of how I deliver my message. It is only then that this discourse I am carrying out will be effective.

As an example, my ongoing collection “Gazing at the crossroads of civilization,” is a long and pleasant work of research and expression. It would be interesting to finalize this artistic chapter with a book, as a compendium where art could be used to reveal and explain all the architectural symbolisms that humankind has engraved on the face of the earth for millennia. So message in the bottle, if you know an editor!

While your illustrations seem to suggest utopic visions and fantastical worlds, what real-world issues and themes in how man relates to built spaces and nature do your drawings seek to draw out?

Since ancient times, utopian architecture has been dreamed of as an assignable place (ATOPOS) expressing an exit from history. Visions of cities without time could be illustrated, compiling a moral vision of the world.

Nowadays, people seem disconnected from their built environment, using the built space for their needs but not because it provides a specific relation between the spatial configuration and our body and mind. Architecture is slowly losing that fundamental principle of inspiring the spirit and triggering sensorial experiences; the small intimate moments that imbue a space with transcendental qualities are now at the mercy of capital and economy.

Like Hegel would say, Art and Architecture do not exist to teach moral lessons, or imitate nature, or assuage feelings; its aim is the representation of the Spirit; in sensorial form, it is the shining through of the absolute, materializing finally into an external sensorial object. Appearance is essential for the truth. Thus architecture has to be conceived as the sensuous presentation of the truth of a place.

Domus chrisalys, 55 x 70 cm

Massada

It is human to seek out beauty in things; how would you describe the beauty that you seek in what you do as an artist and architect?

The notion of beauty and the sublime is a delicate theme that has been debated by many philosophers since the time of Edmund Burke, Kant, Hegel, Benjamin, Heidegger, or even Bachelard.

I think the notion of aesthetics comes between imagination and real purposiveness. Beauty is part of the imagination, imbued with a power to draw out pleasure in its beholders through sensorial experiences.

I agree with Kant and Burke on their analysis of beauty and aesthetic principles. I concur that these are two domains that are interconnected and this is something that I aim to translate in my artworks.

On one hand, I agree with Burke’s principle that there is a logic to taste: the capacity to sense, while nature can be enlightened with knowledge, practice, and frequent exercise. Beauty sans concept is represented as an object or space of universal satisfaction that is determined by the power of judgment, a subjective universality, or intersubjectivity.

On the other, I do believe in the possibility for an object or space as represented by art and architecture to reach a beautiful, even sublime quality even if it is perceived without physical representation or an end. Piranesi and M.C Escher for example mastered that notion in my opinion, along with De Chirico and his metaphysical paintings

For architecture, the rotunda, for example, has a noble effect because of its seemingly infinite aspect. You cannot fix a boundary, and the notion of beauty appears because your imagination has no rest.

Thus beauty has to combine both notions, offering that intersubjectivity, the common-sense based and logical standard necessary for universal communicability (which, of course, means that not everyone will agree or be pleased with what you perceive as beautiful), and free will.

This is why I developed this technique called traitillism, where the abstract is interwoven with the figurative. The sensation of beauty I am trying to attain in my drawings belongs firstly to the form, fed by the memory of the lines, but also to the possibilities and narratives my work elicits from a reader’s fertile mind. •

Meet Marc’s line of vision at marcbrousse.com