Images Buensalido Architects

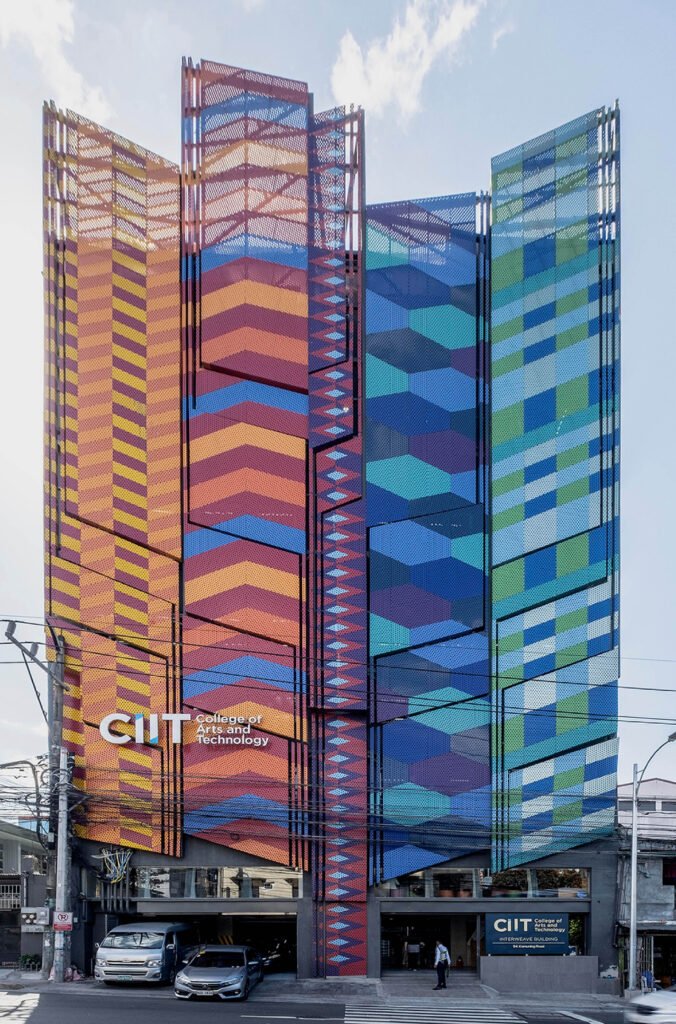

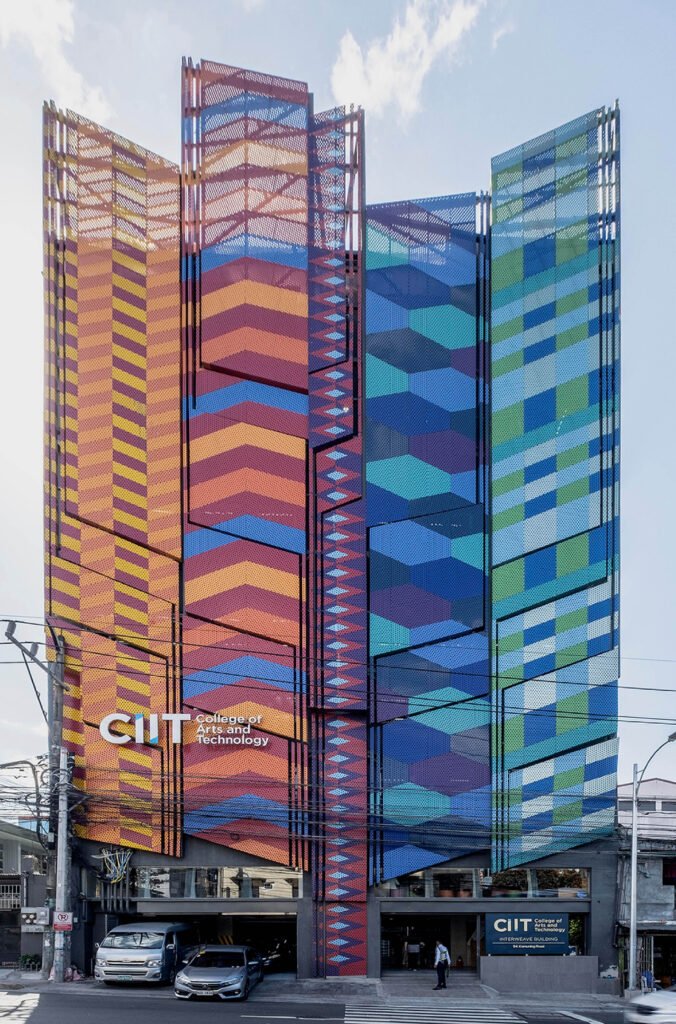

We are told not to judge a book by its cover, but we should in the case of the Interweave Building. That’s because the owner and the architects have much in common. Both espouse pride in being Filipino and possess a collaborative and generous spirit—an outlook expressed both outside and within the building.

Generous

The word “generous” comes from the Latin generōsus from the root verb, gen, which means to beget, create, procreate, reproduce, generate, and engender. From gen comes genus, which means kin, kinfolk, clan, class, and race. Genus also means gender. Genesis means birth and origin, and generōsus, someone well-born or of noble birth.

Adopted by the English language into “generous,” the word would come to mean superior, excellent, dignified, honorable, gallant, and courageous—qualities associated with the nobility and no longer one’s literal birth into landed gentry.

By the 17th century, “generous” and “generosity” had evolved to mean abundant, bountiful, vibrant, rich, potent, and ample, used to describe harvests, praise, color intensity, a portion of food, the alcoholic content of wine, or the size of one’s bosom. Then the words would evolve yet again and be closely linked to “magnanimous,” as persons of high birth were expected to be towards the low-born—giving, bighearted, liberal, charitable, kind, munificent.

Now, what does all of this have to do with Interweave, Buensalido, and WAF?

The generous owners

I’d not heard of CIIT College of Arts and Technology before. Still, its mission and vision of leading the way to a competitive Philippines by “empowering the youth through industry-ready, values-driven and accessible education,” its unpretentious description of its values, and the school’s open-handed culture make me feel hopeful about its graduates.

What you see is what you get—a richly patterned, abundantly colored, eminently practical, and cost-effective exterior with functional interiors enlivened again by vibrant hues, and a foundation and structure faithful to the owners’ benevolent concern for the environment. Here’s more from the owners:

“We’ve always stood for a laid-back campus culture that provides a sense of community and familiarity. Elevators are available to be used by everyone—students and school administrators alike. Our faculty also implements this through the communal workspace with uniform tables, chairs, and rolling cabinets. No one, not even our president Mr. O, has their own private office. From photography and recording studios to drawing rooms and computer labs, there’s room for every kind of creator. We’ve made sure to outfit them with quality equipment that, like the software apps we give you access to, are in line with the industry-utilized standard technology. There’s even a 3D printer available for you to print your creations into reality.”

The school has tablets at each classroom door displaying electronic schedules. The 6th-floor lobby has curved monitor gaming PCs with student-created games! And their library-café, where faculty and students hang out, has a graphic novel section. Best of all, it’s got “great internet and power outlets on the floor and at every table.”

They sound like liberal, largehearted folk. Practical where they need to be without skimping on students’ needs. They must be true to their word—growing a school from 21 students in a dozen years to 1200 in the midst of a pandemic is proof of the pudding.

The generous boss

Jason Buensalido, meanwhile, impresses me with the generosity with which he speaks about his people and with everyone the firm works. He’s the overachiever in school no one could get mad at because he’s nice to everyone. He’s the acquaintance on Facebook and Viber who makes you feel like a friend. He’s the interviewee journalists love because no question is too stupid. He’s generous with his time, and he gives you everything you need—soundbites, photos, floorplans, and now, he’s even provided us with a video clip, unsolicited.

Oh, and he, too, runs a school called Foundree, with partners and friends to want to give to architecture students and graduates what they didn’t have when they were young—better education, mentorship, and preparation for licensure exams and setting up practices.

He’s the man who lets people take credit for their contributions. He’s the boss who grooms employees into partners. When Kanto interviewed Buensalido about his other WAF shortlisted project, the Freedom Memorial Museum, he quickly pointed out we should include Em Eliseo, one of B+A’s partners, in the credits. He did it again when we asked to interview him on this one.

Here’s the project description Buensalido sent, followed by Kanto’s interview with him and his associate, Jerome Bautista. You’ll see what I mean.

The School

CIIT is a College of Arts and Technology that offers multi-media, fine arts, computer science, and game development courses. They needed to transfer their existing campus to a building to answer the growing space requirements of their increasing number of enrollees.

They had purchased an old four-story building in the middle of a busy residential neighborhood undergoing a DIY-type of rapid gentrification, where houses are haphazardly converting into various commercial uses to maximize the rising land value. The building formerly housed a bar on the ground floor, a restaurant at the top level, and some residential and commercial rental units in between.

In the spirit of practicality and sustainability, the owners decided to retain the existing structural members of the existing building and retrofit them to accommodate additional floors above.

Team

The project was a collaboration between two groups. Aecon Builders Co. would be the architect-of-record and in charge of planning and detailed drawings, while Buensalido+Architects would be the exterior architect and designer for vital public areas.

Plan

Sitting on a 450-square-meter plot, the existing four-story building comprised only 400 square meters. Therefore, the plan was to maximize space using the current structural frame of the building and effectively move the projected number of students up and down the different levels through an engaging vertical circulation strategy.

We provided a central staircase that doubles as a social space. It accommodates students passing through and serves as an ‘amphitheater’ for pin-up huddles and lectures, creative shows, or for just hanging out. Once we established the central feature, Aecon fit the classrooms in the leftover space in the most efficient manner.

The existing building didn’t have a basement. Aecon could not add sub-level parking or set parking above ground because the existing columns had a maximum carrying capacity despite post-retrofit. Therefore, most of the ground floor was dedicated to parking, leaving a small entry lobby that leads directly to the central staircase and lift, preceded by an outdoor lounge and vertical garden.

The main common space would be on the second floor, with the main reception, student lounge, library, and cafeteria, distributed around the central core. The reception has a double-height ceiling overlooked by the administrative offices, faculty, and employee lounges above at the third.

The fourth and fifth floors hold lecture rooms, creative studios, and computer laboratories, accommodating the 1,200 enrollees. The topmost level is the gym, which hosts college events and parties, and a mezzanine level for bleachers.

Structural

The biggest challenge was adding the three top levels, which called for strategic structural retrofitting. After demolishing the non-structural partitions, the ground floor slab was removed to reveal the original footings. On this were laid new footings that would carry new steel columns (two steel columns were strapped around each existing concrete column and covered with a second layer of reinforced concrete). These new steel columns would not only go up beyond the existing four floors to carry the frames of the three new floors above but would also carry the double steel beams flanked around each existing concrete beam as additional bracing to complete the retrofitting of the project.

Exterior

Being an art school, the clients wanted the façade to express creativity, experimentation, and freedom. Unfortunately, the structurally retrofitted building gave no elbow room for creative three-dimensional expression on the main shell without a high cost to the owners. The solution, therefore, was a second skin detached from the building, which allowed freedom on three-dimensional manipulation without driving up the price too much.

CIIT’s goal is to be at the forefront of the intersection of arts and technology education while asserting Filipino ownership of the company, pride in Filipino identity, and its sustainability ethic.

These ideas were juxtaposed in the composition of the façade. The skin profile takes the form of a canopy that grows out from a central core, like a tree. This profile is then broken into smaller segments, sliced through lines in motion in a chipboard pattern—a nod to technology, a core strength of the school. Finally, textile weave patterns from Filipino tribes were abstracted into a vibrant, geometric network of shapes and colors.

Interiors

To address cost limitations, the industrial aesthetic—an open ceiling with exposed utilities, unpainted walls, and polished concrete for the floors—kept costs down and also lays bare the history of the building. Old and new utilities are exposed, construction joints between original and new structures are visible, as are the additional steel retrofitting members that reinforce the old concrete frame.

For visual language consistency in and out, the abstracted Filipino weave patterns were brought inside via colored wooden strips attached to the ceiling. The energetic hues create a sense of movement within the interiors, starting and ending at various access points to different spaces, serving as a navigational tool.

Optimistic Architecture

Filipinos have a deep-seated psychological struggle with our past that manifests today in a defeatist, victim mentality. The colonial mentality we struggle with surfaces, for example, in our urban fabric that is a hodge-podge of foreign styles, some inappropriate to our cultural context and climate.

The mentality of being small—”I am just a speck of dust in the scheme of things, so I cannot do anything about anything anyway,” is why Filipinos are resigned to corruption in government, inequality between rich and poor, poorly designed urban spaces, and so on. It could well be this predicament that has developed in us a resilient spirit. But if it is resilience that allows exclusivity and imbalance to prosper, then it should be corrected.

The resilience we celebrate is the Filipino’s relentless belief that tomorrow will be a better day. Albeit a passive attitude, we can turn resilience into an active and intentional attitude. This optimism and positivity, this idea of hope, is what Filipino Architecture should be about. Through expressive forms, vibrant colors, and an assertive presence, we convey the celebratory character of Filipino fiestas and festivities in architecture. Such nature would serve as both motivation and urban renewal strategy. Amidst the messy and uninspired gentrification in this corner of Manila, the hope is the school building sets a celebratory and uplifting precedent for others to echo when they develop their properties.

Buensalido + Architects Project Team:

- Jason Buensalido – Principal Architect

- Jerome Bautista – Associate Architect

- Rissa Espiritu – Project Architect

- Larry Espino – Technical Innovations Architect

The generous principal

Kanto: Jason, the building owners and Aecon must be thrilled by CIIT shortlisted at the WAF!

Jason: They were both happy about the news! We asked for their blessing and support before entering WAF, of course, so they were aware and have supported us since. Even before WAF, the owners have been proud of the building, being their first build as a school. (They rented an interior space for their previous campus.) Their story is the story behind the design, and they’ve plastered it on the school walls so the users know what the building represents, which helps the people form an attachment to the campus.

Will Aecon be presenting alongside you at WAF?

Jason: Though we invited them, both the owners and Aecon will not be joining us for the presentation but expressed their full support in other ways.

Why was there a need for Aecon to do the planning and detailed drawings?

Jason: We came into the picture at the latter part of planning. AECON had already been engaged as the architect-of-record and had the floor plans and basic exterior shell designed and costed out. The client brought in B+A as they were looking for a unique design expression of their values. They wanted to use design to communicate their identity to the world, the admin, the faculty, and the students. We told them we would agree only if we had AECON’s blessing, which they gave right away. They agreed for us to take the lead on the façade design and the common areas, from conceptualization, detailing, and construction supervision while also allowing us to suggest tweaks in the other levels. The client delineated the scope of each group.

How did B+A and Aecon collaborate? How did your ideas impact their plans and vice versa?

Jason: Much of the design drawings had already been done. B+A couldn’t do much structural alteration as these were already costed out. We were asked not to touch the fenestrations as deals with suppliers and contractors had already been made. This was one of the reasons for the skin proposal, a strategy that could have maximum visual impact and the least cost implications.

We designed everything in the shared spaces—the lobbies, circulatory spaces, reception, student lounge, cafeteria, and library. We were limited here by the low ceiling height, as these areas occupy the mezzanine level of the original four-story building. We carried through the visual logic of the façade into the interiors, a pattern language that AECON and the owners themselves applied in areas not part of B+A’s scope. They based their ideas on our designs, which we then tweaked for coherence when needed.

Jerome: For the interior design, the space planning was already ironed out, so we designed around it. We did, however, have a hand in the design of the utilities (mechanical, electrical, and fire protection), recommending an organizational language that echoes the directional language of the ceiling fins.

For the façade design: While we worked around the structural plans of the building, we still had to compute the total weight of the second skin, its sub-framing, and our proposed façade structural framing early on and coordinate it with AECON for structural design verification, so there was a lot of collaboration on that end.

Which rooms face the street?

Jason: They would be the entry lobby on the ground preceded by a mini-outdoor waiting area, the student lounge and library on the second floor, classrooms and labs at the upper floors, and the gym at the topmost level. The building is along Kamuning Street in Quezon City. The façade faces northwest.

The rooms facing the street are airconditioned? Tell us about the conditions for natural ventilation.

Jason: They, along with the other rooms not facing the street, are air-conditioned as directed by the clients. All the spaces have the option to naturally ventilate through operable windows, of course. But this isn’t desirable due to the polluted air from heavy street traffic. The only fully naturally ventilated spaces are the circulation spaces and the gymnasium. If the school were to open the exterior windows, the air would enter the rooms and rise to the topmost floor (where the gym is) through the stack effect, and the hot air would dissipate through the storm-louvered walls lining the gym and multi-purpose space.

Jerome: Low-velocity energy-efficient industrial ceiling fans are provided at the topmost floor to ensure efficient airflow and improve air movement across the floors, which help increase the effectiveness of cross ventilation.

With the building facing northwest, it’s great you used a brise soleil. What is it made of? How big are the holes? Am wondering how much shade it provides and how much light gets through.

Jason: Aluminum composite panels with nano-coating, which makes them resistant to dust settling and staining. The perforations are about 25 mm in diameter, spaced approximately 25 mm from each other. We don’t have an exact figure, but it effectively reduces glare and radiant heat from the cityscape. While it still allows light and wind to filter through, another function of the skin is to block off the distractions of the city—clutter, noise, and even dust—to help the students concentrate in class.

What is the color of the brise soleil material facing inwards? Any particular reason for the color?

Jason: At first, we wanted the color of the skin interior to be the same as outside, but for financial reasons and to lessen distractions, we settled on light gray, for ease of maintenance and prevent the interiors from being too dark.

How were the colorful wood strips attached to the concrete ceiling?

Jerome: We screwed ¾-inch marine plywood substrates directly to the slab first on the areas where the wood strips will be, then the strips were glued and screwed on the said substrate.

I was wondering whether their number and depth help to cut down noise in the hallways.

Jason: We never had the opportunity to test this as the project didn’t have an acoustic engineer on board. But I would imagine that it helps diffuse the sound, being made of softwood, designed in a baffle pattern, and laid out circuitously throughout the common spaces.

Have you been able to visit the school with students in them? Have you asked them how they like it? How have they compared it with their old campus?

Jason: Yes! We visited the school and spoke to the owners, teachers, and some students. The owners admitted that they were initially hesitant about the design but realized that the space is not for them but for the students. They’ve said that the building is a success because, through the design, they can connect easily with the teachers and students on their vision for the school. They also see the students enjoying the campus very much.

The teachers appreciate that the spaces are not drab or clinical, but instead are playful and create an environment where they feel the students are more receptive to what they teach. They also mentioned that they don’t feel they are going to ‘work’ as they are relaxed and comfortable in the environment that helps reduce stress.

Both the teachers and students say the vibrancy of color and lighting in classrooms and common spaces affect their mood positively. Sharing with you a video when we spoke with them:

Has the school made any changes to the classrooms and common areas set up because of the pandemic?

Jason: They haven’t resumed face-to-face classes since the lockdown, so aside from the usual safety protocols, such as contact tracing, physical distancing, installation of sanitation stations, purchasing of portable HEPA and UV filters, and acrylic barriers, they haven’t done any structural changes with the school yet. A big reason is that they quickly converted all the classes to virtual.

They are an arts and tech school with innovation at the core of their value system, and the speed with which they adopted the full online distance learning setup is exemplary. They even increased their student retention rate to 96 percent! The satisfaction rating of the students with teachers has also gone up. They are currently still developing and planning the full potential of virtual learning, studying the potential to reach the entire Philippines and even abroad.

However, they believe face-to-face classes are pivotal to learning and perhaps will apply a blended setup when there no longer is a need for lockdowns. They will surely make structural changes to the school before then. Furthermore, we are in talks to design their new campus in the vicinity soon (from the ground up this time), where we can take our learnings in this existing structure and design better this time around.

How would you alter the school typology now that we have all realized the need to safeguard wellbeing and health?

Jason: Schools all over the world are already changing, shifting from the traditional classroom set-up towards much more flexible spaces, where students have the autonomy to learn at their own way and pace. Teachers are more and more becoming facilitators of learning rather than lecturers of information, and students are being trained to be active and empowered learners.

Aside from these changes in pedagogy which have a significant impact on space, COVID has bumped up health, wellness, and safety to be top priorities in coming iterations of future school designs. There will be a heightened focus on essentials—more natural light in the interiors, better natural ventilation, flexible space planning, to name a few. More green spaces, as plants filter air and absorb carbon monoxide. Aside from this, the green spaces could be used for urban farming and food production, encouraging students to take active roles in solving global issues such as food sourcing.

Active design will play a central role in the circulatory spaces—floor to floor and building to building—encouraging students to walk or bike, which could be complemented by being intentional about enhancing the pedestrian experience.

Designers would have to dive deeper into material specification, ensuring no toxins, low-VOC, and bacteria-resistance. Higher levels of filtering systems, especially in artificially ventilated spaces will be integrated as well.

Jerome: The pandemic has exposed the vulnerabilities of archetypal typologies, I believe that flexible spaces and, ultimately, flexible and hybrid typologies will be the next frontier.

I am so impressed you credit your people, Jason. Tell us a bit about your associate, Jerome. What did he bring to the table for this project?

Jerome is the lead architect for the project, now an associate architect and a partner in the firm. We both led design discussions when we were developing the designs with the team, and he was the point person and primary decision-maker at client and site meetings.

Tell us also about Larry, your Technical Innovations Architect. What did he bring to the table?

Jason: Larry ensured that the technical aspects of the design were addressed and well-coordinated. He collaborated with the engineers and suppliers to ensure the buildability of the team’s ideas and took the lead in the preparation of the details. What happens in the industry is that when concepts are detailed into technical drawings, they often lose the original language and essence of the concept. One of his main roles is to protect the original intent and essence of the concept, while negotiating the complexities of implementation such as cost, maintenance, buildability, availability of materials, and limitations of the site, among many other factors.

Jerome: Since he took the lead on the development of the design details—from the smallest connection detail, to how all the different building systems play and interact with each other—his presence during site meetings and inspections is invaluable. His extensive experience and familiarity with the building materials we specified in the project proved to be a real asset to the team, not only during the design phase but also during construction, by providing practical and efficient solutions whenever the need arose.

Tell us also about Rissa’s contribution.

Jason: Rissa wasn’t the original project architect of CIIT, but when she took over, she made sure she knew all the drawings especially during construction, often being the one who would correspond with the builders for the queries they had. She would also visit the site along with the team to ensure that the interpretation of the drawings is correct.

Jerome: Rissa played a pivotal role in the success of the project, from initiating regular internal update meetings and discussions within the team to make sure that everyone is on the same page, to being completely obsessed with checking the façade during site meetings to ensure that every cell is correct in size and angle, and the exact color and shade we envisioned and specified.

Thanks! And best of luck, Jason and team!

Jason and Jerome: Thank you so much, Judith and Team Kanto!

So, here’s a guy who’s schooling us in the art of collaboration and being a decent human being. And here’s a school that believes in critical thinking, innovation, teamwork, and doing the right thing. The two make an excellent match.

The University of Notre Dame has a project called The Science of Generosity Initiative, established in 2009. The initiative funds projects like, “The Family Cycle of Generosity,” “The Causes, Manifestations, and Consequences of Generosity,” and “The Social Contagion of Generosity.” They study what makes people generous and investigate broad moral questions related to the common good. Its founders believe that more liberal giving could “accomplish world-transforming change.”

Will the World Architecture Festival sense the owners’ and the architects’ collaborative and giving spirit in the Interweave Building? I hope so. The important thing is the school got built and the students are happy. Could the schools of Buensalido and CIIT spread the contagion of kindness, bigheartedness, and courage more quickly, please? •

7 Responses