Interview Patrick Kasingsing

Images Yen-An Chen of Atelier YenAn

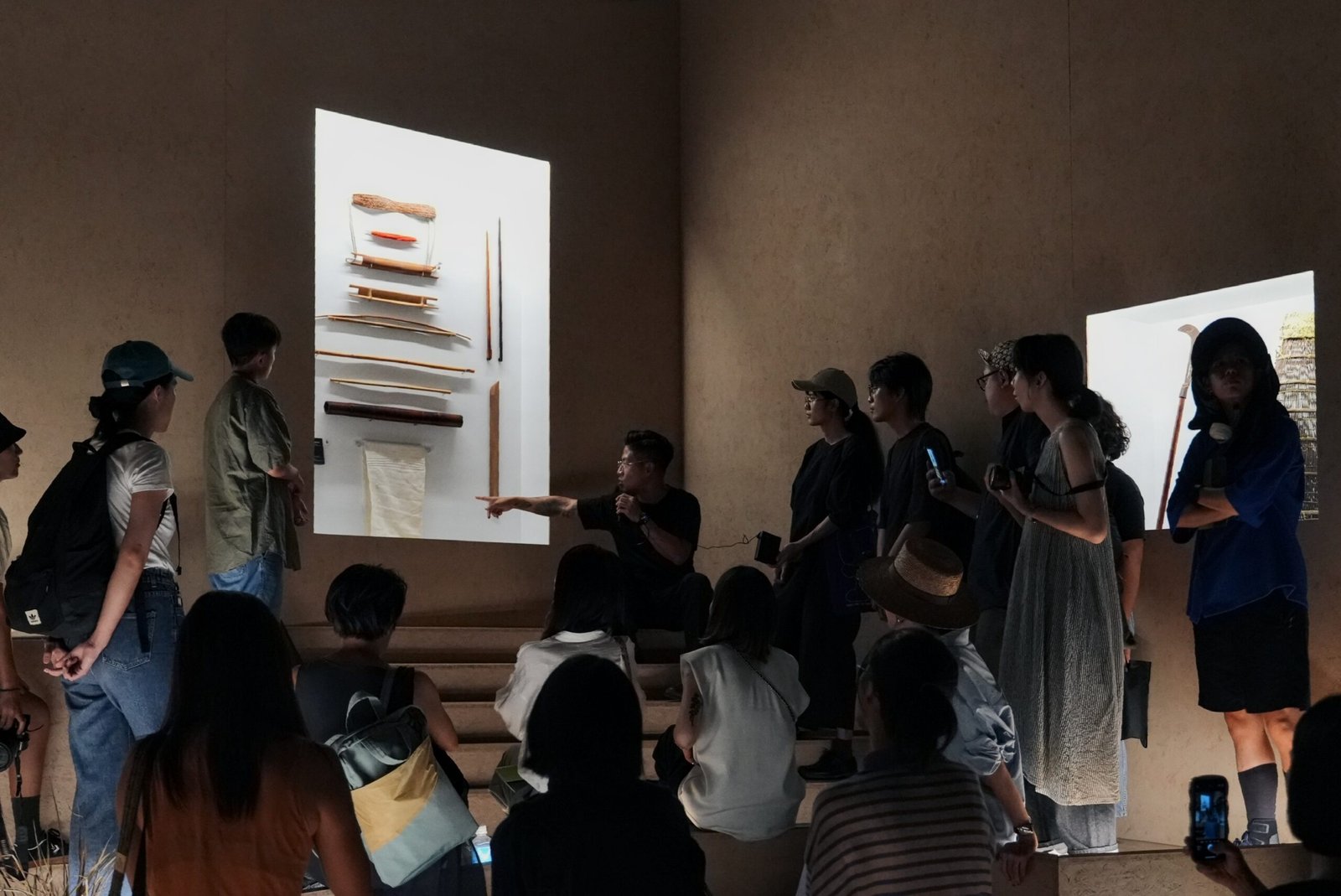

Hello Yen-An! Happy to have you over at Kanto! You’ve now had a glimpse of Filipino design energy through Astrolikha Spaces and the broader DesignWeek Philippines. Was there a moment, or idea, be it from moderators, panelists, or audiences, that surprised you or felt especially resonant?

Yen-An Chen , studio founder, Atelier YenAn: It was my pleasure to share my experiences and practices during Design Week Philippines. One of the most meaningful questions from the audience was about how I choose topics that have a real impact on society. I was deeply moved to see that people from different cultural backgrounds are also interested in the same issues. It reminded me that, despite our diverse cultures, we all share a common desire to discuss the challenges and concerns that matter to us individually and collectively.

During the Astrolikha Spaces session, ginhawa was described as a kind of well-being, linked to comfort, dignity, and cultural care. Did this idea feel familiar to you, and is there a similar value or concern, such as ginhawa, in Taiwanese design culture?

From my understanding, ginhawa goes beyond physical comfort; it encompasses emotional, social, and cultural well-being. In that sense, I feel that ginhawa aligns perfectly with my design philosophy. As designers, we can challenge ourselves to explore and express well-being within society. There are many ways to pursue this goal, and in my case, I seek to raise awareness and spark social interest through more provocative approaches—both visually and experientially. By doing so, I hope to inspire people in Taiwan to gain the confidence to discuss our own culture and issues, and ultimately, to pursue our shared sense of well-being.

The Neon Lamp Series is an ensemble of sculptural neon lamps that reimagines the rhythm of the disappearing neon industry.

The series is an evolving exploration of neon’s unique craft and luminous expression.

Based on your Astrolikha discussion and what you now know about the Philippines, what are the low-hanging fruit for collaboration and discourse that you see between Taiwanese and Filipino artists and designers? What shared design challenges or opportunities are there that can be pursued between the two nations?

Through this discussion and a deeper understanding of the Philippines, I see many possibilities for collaboration between Taiwanese and Filipino artists and designers. Both societies are constantly navigating between tradition and modernity, global influence and local identity.

One clear starting point is our shared concern for cultural well-being, reflected in the Filipino concept of ginhawa. Both Taiwan and the Philippines value community and cultural roots, yet face similar challenges in preserving authenticity while embracing innovation. Collaborative projects that explore everyday well-being, environmental awareness, and social empathy could foster meaningful dialogue.

There is also great potential in design education and co-creation, where we can exchange approaches to storytelling, craft, and technology. By reinterpreting local narratives together, we can transform traditional expressions into contemporary design languages that speak to both regional and global audiences.

Ultimately, our shared challenge and opportunity is to express cultural identity without reducing it to nostalgia or decoration. By focusing on empathy, relevance, and cultural confidence, Taiwanese and Filipino creatives can co-create works that embody a broader sense of Asian well-being, resilience, and imagination.

That’s wonderful to hear. Now, your work often turns cultural stories into objects and exhibitions. How do you decide what parts of Taiwanese identity to show, and how do you avoid reducing culture into mere aesthetic or subject of nostalgia?

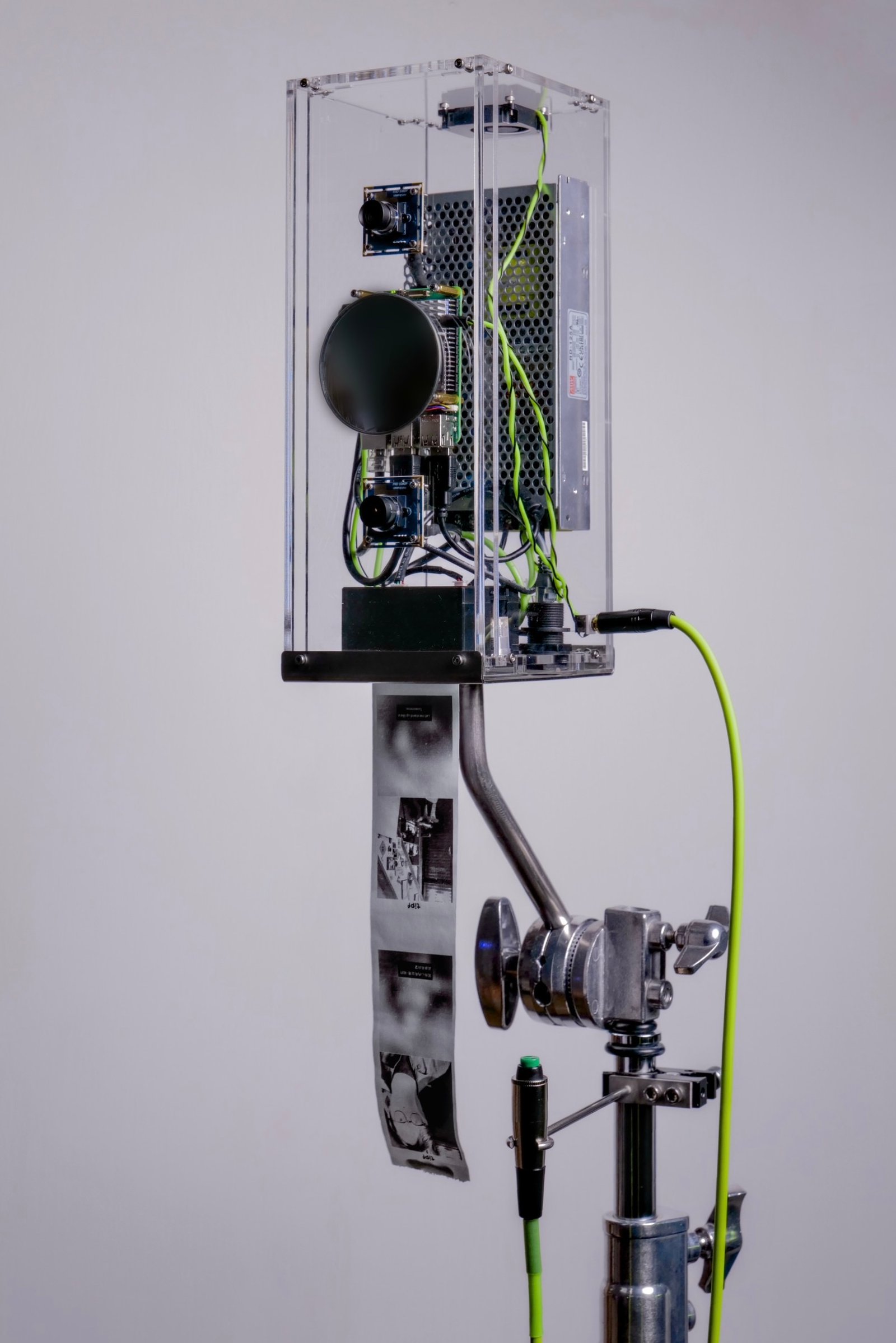

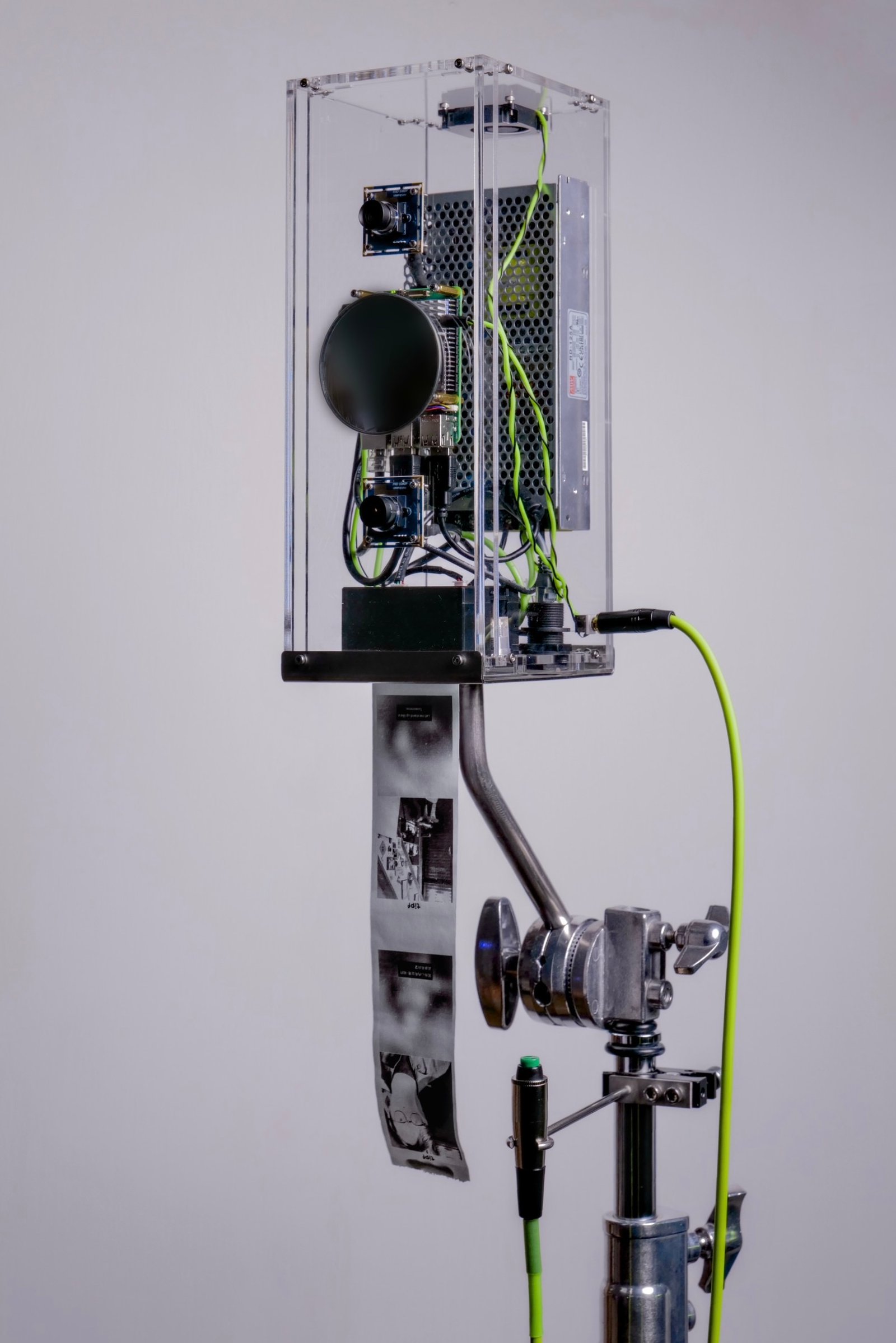

Personally, I believe there are many topics worth discussing, and I see my role as amplifying the often-overlooked or underestimated issues. That’s why we started the project p.n.g. to open conversations about pollution, politics, nation, normality, gender, generation, and more. We have a long list of themes we want to explore.

The name “p.n.g.” is intentionally flexible; for each project, we choose a new combination of meanings to make our statement. The term “.png” comes from Portable Network Graphics, a file format that compresses images without losing quality, and that’s precisely what we aim to do: to transform complex issues into accessible forms.

We believe that serious topics can be discussed in lighter, more approachable ways to better connect with the public. As long as we keep this principle in mind, our designs can be both visually engaging and culturally meaningful at the same time.

Like your Filipino peers, Taiwanese designers often work at the intersection between local traditions and global audiences. How do you keep cultural detail and meaning intact when designing for people or places that may not know the full context?

I believe there are many ways to engage global audiences, but my main concern is whether we can accurately translate our culture and roots without losing their meaning in the process. It can be challenging to convey the background and nuances of our culture to those unfamiliar with it. However, my goal is to reach people who may lack confidence in our own cultural identity. By doing so, we not only strengthen our sense of self but also share our culture with the world.

If communicating with global audiences is the goal, we need to establish a clear narrative and cultural pathway that helps them understand our origins. It’s not an easy task, but I believe it’s a challenge that all of us, as content creators, must face together.

Let’s close with AI, a topic that was explored in great detail by your nation last year for Taiwan Design Week. AI tools are now being used to generate images or narratives quickly, but often at the expense of cultural depth and soul. How can one protect the meaning, texture, and humanity of Taiwanese stories in one’s work, especially when using digital tools?

Personally, I rarely use AI tools to create my vision from scratch. I usually develop the concept in my mind first and build a solid foundation before bringing it into AI. I believe that when used properly, AI can save a lot of time — I’ve benefited from its assistance in improving visual communication, especially when preparing proposals. It’s also a helpful way to test whether an idea works visually.

However, I don’t fully trust images generated entirely by AI, at least not yet. While AI can search vast amounts of online data and produce stunning visuals in seconds, it often places cultural elements in the wrong context. The results may look convincing, but inaccurate representations can distort or harm cultural understanding.

As creators, I believe we have a responsibility to engage with AI thoughtfully. The images we produce are powerful tools of communication. My primary concern isn’t the lack of cultural depth, but the risk of mixing or misusing cultural symbols, which can unintentionally harm those working to preserve their own heritage.

Indeed. And like any tool, it should stay guided by human judgment. The horizons AI opens will only be as inclusive and attuned to kaginhawaan as we make them. Thank you, Yen-An, for your time! •

Kanto thanks the Taiwan Design Research Institute for making this interview possible

One Response