Introduction and images Studio Mariano

Interview Patrick Kasingsing

The Andamyo began as an entry to the B+abble Micro-Locale “Sit Happens” design competition, which asked participants to create a stool inspired by personal experiences of place and culture. Without a specific province or hometown to reference, I drew from a formative part of my childhood—visits to construction sites with my late father, a mechanical engineer. I was always drawn to the wooden scaffolds I saw on site. They looked like jungle gyms for adults.

Now, as an interior designer still often at construction sites, I continue to find scaffolds compelling; the image they conjure—an intricate mesh of vertical and horizontal supports, joined at points that appear arbitrary yet can bear the weight of both tools and people—always seemed ripe for formal exploration.

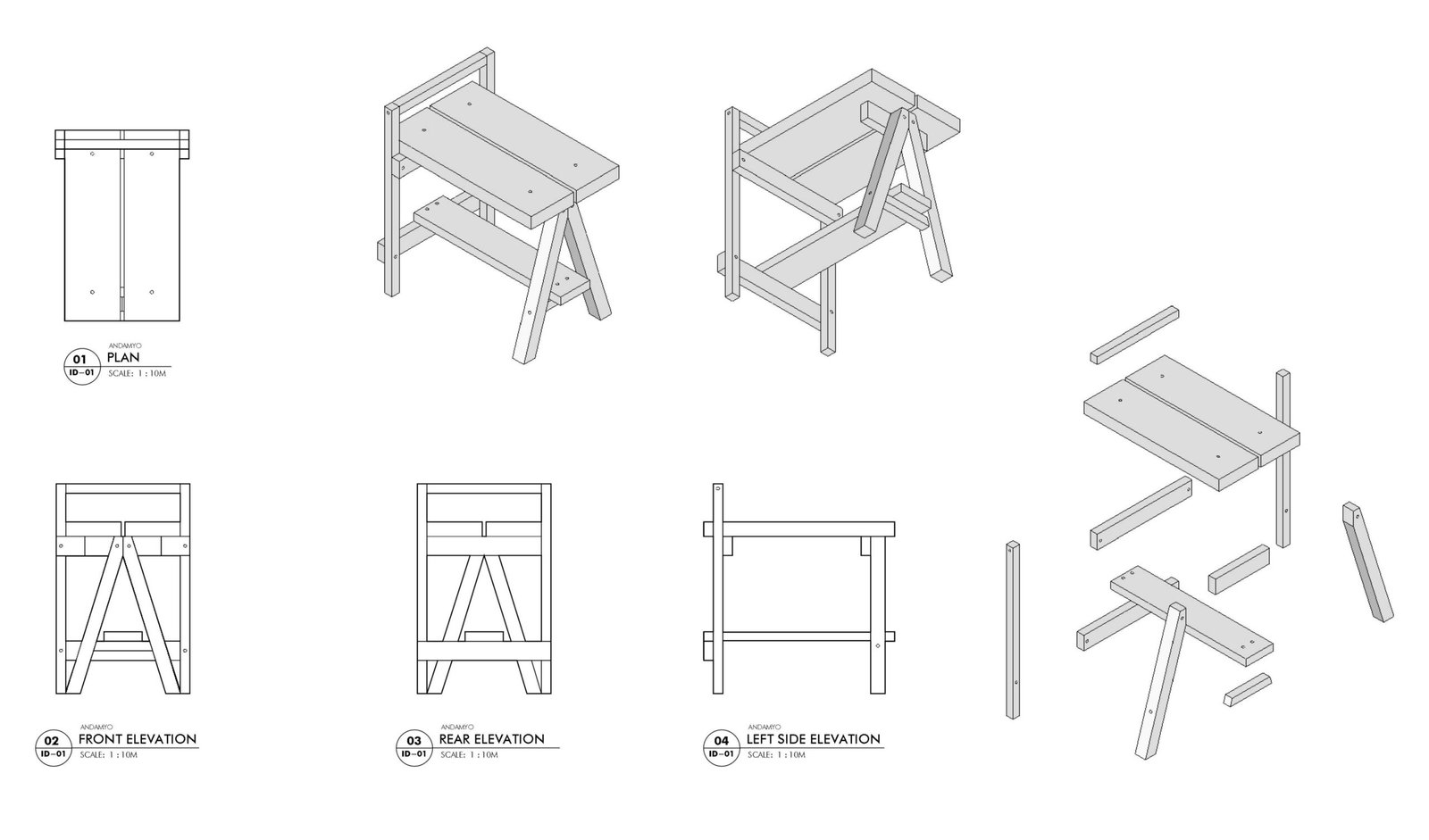

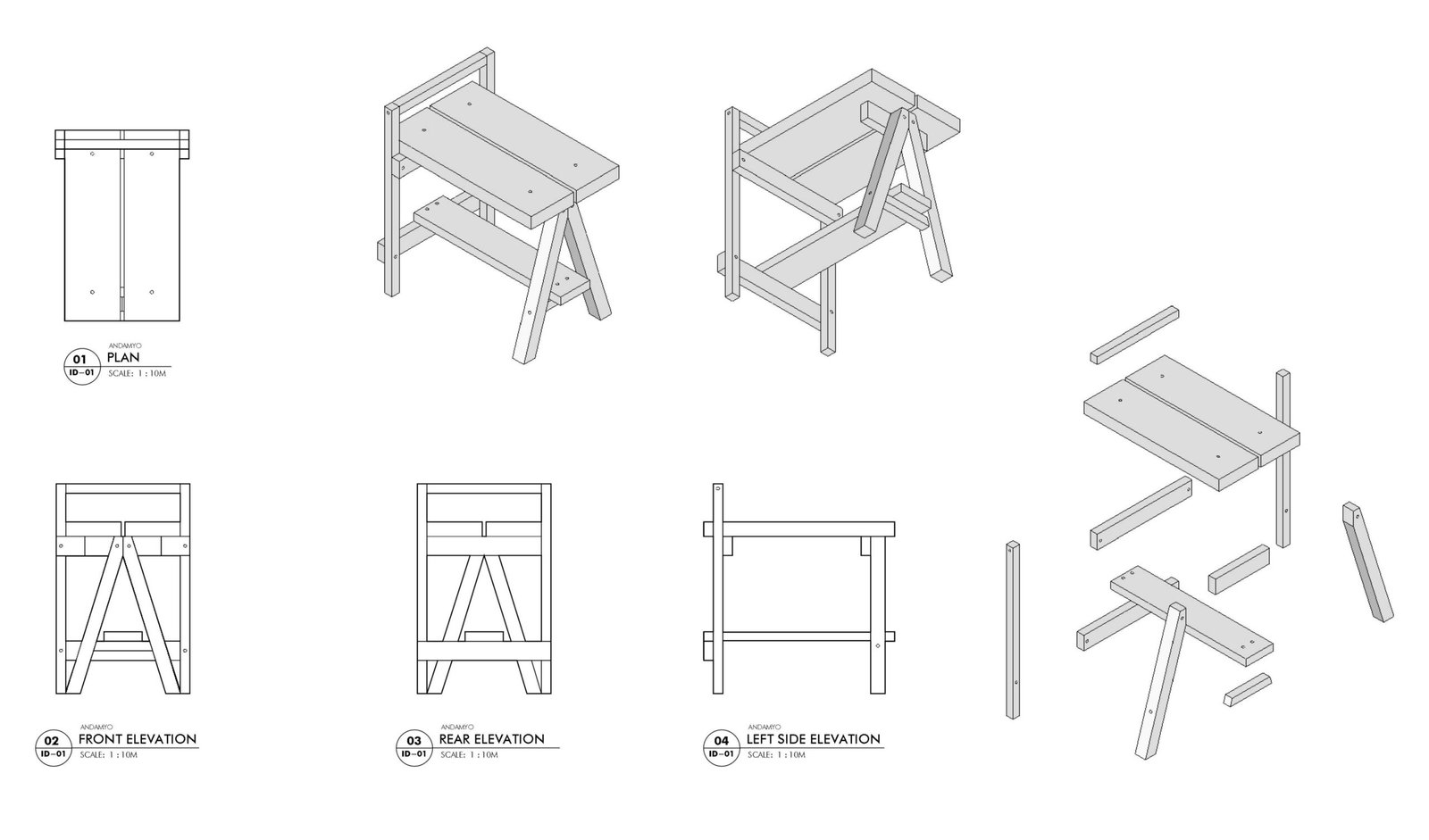

This memory formed the foundation of the Andamyo, named after the Filipino word for scaffolding. The design references the wooden structures typical of residential construction sites, held together by mismatched members, diagonal supports, and a kind of organized disorder. It’s a study in balance, resourcefulness, and the logic of things that work without being over-designed.

To stay close to that reference, I used basic components and straightforward construction techniques. The challenge was translating that raw, improvised character into something more resolved, without losing the qualities that made it interesting to begin with. I leaned into asymmetry, adjusted proportions, and let some parts protrude to create depth and variation. Varying the thickness of components added another layer of complexity.

My entry didn’t make the competition shortlist. A month later, I revisited the Andamyo with a new lens: from it being a competition submission to that of a conceptual project I could share on Instagram and in my portfolio. The response was encouraging, and it pushed me to develop a working prototype. I started with balsa wood scale models to test proportion, followed by a full-sized cardboard mockup to assess spatial presence and visual weight. With a modest budget, I produced a single prototype, which I lent to friends for testing in everyday settings. That informal trial phase, combined with my use, gave me confidence to launch a small pre-order batch, which was well received.

Originally conceived as a stool, I’ve since dropped the descriptor. The Andamyo can serve as stool, side table, or display. It adapts to need—an object of support and utility, much like its namesake.

Hello there, Migo! Welcome to Kanto, and thank you again for sharing the story of the Andamyo with us. Mies van der Rohe once said a chair is a complex object to design; do you agree? What do you find to be the most challenging stage or aspect of designing a chair?

Migo Mariano, Studio Mariano principal, and designer of Andamyo: I agree. It’s difficult because designers must care. From a designer’s perspective, a chair is not purely utilitarian–just any object that one sits on. It’s a thoughtfully designed object created with the user’s comfort in mind. Caring about the output makes it difficult and also worthwhile. It makes a designer obsess over every single detail. As part of an interior space, we have a very close level of interaction with chairs. Our bodies have direct contact with these objects. We touch, feel, and physically experience them. That’s why designers strive to come up with chairs that are beautiful and comfortable.

Technical and anthropometric factors are critical in chair design. They dictate structural performance and the level of user comfort, respectively. These are non-negotiables determined from the intended use or type of chair. The form and appearance develop around these factors. Negotiating between them and bringing them all together is the challenging part because they are not always in agreement with one another. But it’s also the most fulfilling part.

On the more practical side of things, prototyping is challenging because it requires two valuable resources: time and money. You must be creative to maximize what’s available to you at a particular time.

How important is narrative and memory in furniture design? Do you think storytelling plays a pivotal role in how a piece succeeds or connects?

Narrative in furniture design adds depth to a piece. Interest usually begins from its appearance. We are generally drawn because of how a piece looks, but it becomes more interesting when you learn about the inspiration and the stories behind it. A sincere narrative or concept helps people understand the piece better. It gives you an idea about how the design arrived at its final form and appearance. I cannot stress enough the importance of sincerity in terms of concept. People can recognize when design concepts are just flowery words and lack substance.

Memory is also a valuable component. It lends another layer of appreciation. This is where the designer may draw inspiration from–personal experiences and memorable events. Memory is not only the images we remember but the entire experience. There’s an emotional component to it. It allows people to connect with and relate to your design at a deeper level.

Just as an example, a schoolmate of mine, whom I hadn’t seen and talked to for years, messaged me about the Andamyo. He expressed his appreciation for it because he recognized the references to the scaffolding and recalled fond memories of growing up around construction sites. The story behind the piece resonated with him through a common experience that we shared.

After prototyping and the informal stress tests with friends, how else did the Andamyo evolve, be it in design, function, or how you saw it fitting into people’s spaces?

The Andamyo’s evolution in terms of design or form happened even before the stress tests. The first version was the competition entry. The second version was a more polished one made to be shared online as a conceptual piece. The third and current version was based on practical considerations of construction and potential use.

The major change was the removal of a cross brace that ran underneath and along the gap between the two surface planks, just a bit wider than the gap, allowing the planks to rest on it. First, I realized it was unnecessary. Second, it was an impractical detail. It would have just gathered dust and dirt. Lastly, removing it further simplified construction. All these adjustments and revisions happened during 3D modeling, scale modeling with balsa wood, and 1:1 cardboard modeling. I couldn’t afford multiple prototypes, so I had to make sure that the design I turned over for prototype production was as refined as possible.

What evolved after the stress testing phase was its intended use and the way I chose to name the piece. The feedback from this phase reinforced my initial decision to drop the “stool” descriptor. Calling it just “Andamyo”, instead of “Andamyo Stool”, made sense. Its form and proportions did not readily communicate it as a seating piece. Based on how my friends used it, it registered more as a side table or display platform, but I still refused to label it as such. I chose to leave it open-ended. It’s up to you how you will use it based on how the piece resonates with you. From time to time, I still show the Andamyo in use as a stool, as a reminder that it is inspired by makeshift forms that invite improvisation.

I often work with the guiding principle, “good design is intuitive”. Without instructions, people should understand how a product should be used. But in this case, aligning with the concept, I just let the Andamyo invite curiosity and creativity from its users.

What did the B+Abble competition experience teach you about furniture design? What values do you prioritize when designing furniture?

The B+Abble competition experience taught me the value of a strong narrative or concept translated properly into design, especially in the context of a competition.

When designing furniture, I prioritize establishing a strong and authentic concept from which the design is grounded. It guides the design decisions along the way and sets the design language of the piece. It helps filter ideas. Not all ideas will be used in the final design. Even some good ideas will be discarded. If it’s not aligned with the concept, it will be set aside.

I was pleased with the concept of the Andamyo because I felt it was really sincere and honest. Although my design execution for the competition wasn’t the best, I still believed the concept was strong. Improving the design to its current form was relatively easy because the idea was solid and honest.

To end, do you see the Andamyo as part of a larger design language you’re developing across your fields of practice?

Yes, but I’ll only pursue it if it suits a project, especially for interiors and commissioned pieces. This isn’t something I intend to enforce as a signature style on my clients or collaborators. But I would love to explore this design language in an entire furniture collection and, hopefully, in interiors, too, if anyone’s interested. It’s all about finding ways to make simple, straightforward forms beautiful and interesting. •