Words Patrick Kasingsing

Images Martin Abad Santos for Nazareno Architecture + Design

Loss is universal, inevitable. But there is loss that is sudden and violent, one that leaves a void seemingly too deep to fill. The extrajudicial killings that marked the previous administration’s war on drugs claimed thousands of lives and left behind families drowning in grief, denied even the dignity of proper mourning. Victims were buried in unmarked graves, crammed into deteriorating, overcrowded niches, while some have yet to be found.

Knowing first-hand the destructive nature of substance abuse and the restorative power of resolve and faith, former drug addict-turned-human rights advocate Father Flaviano ‘Flavie’ Villanueva, SVD initiated Dambana ng Paghilom (Shrine of Healing) back in 2020 with Nazareno Architecture + Design. It was conceived to be a sanctuary of remembrance and solace, a structure of stark architectural purity for those whose turbulent lives were unjustly taken, a solemn, peaceful home beneath an open sky for the bereaved to gather, grieve, and heal.

A place for rest

The project began in earnest when Father Flavie approached NA+D studio principal Anthony Nazareno during a family outreach activity in Tayuman, Manila. A site has already been picked, a square plot with an existing mausoleum in La Loma Cemetery, turned over to the priest by the Archdiocese of Caloocan. It was a location pick that signaled the lamentable fact that the city of Caloocan is among the hotspots for drug war-related killings; one of its most notable victims, 17-year-old student Kian delos Santos, was laid to rest in the same cemetery. The commission was emotionally and politically charged from the very beginning, which led its eventual architect to deeply reflect on whether he was the right person for the job.

Father Flavie was unyielding in his purpose to provide a dignified memorial for the victims of extrajudicial killings, especially during the turbulent time of pandemic lockdowns, which so moved Nazareno. He asked to be taken to the proposed site, where he was left aghast at the derelict state of an existing mausoleum, which initially, Father Flavie wanted him to revive. “The moment I saw it, I knew it had to go,” Nazareno states. “It was dense, enclosed, oppressive. It was a cylindrical volume that is so dark and heavy, with the only source of light coming from its narrow entrance. The space I envisioned for the memorial needed light, space, and air.” The mausoleum was eventually cleared.

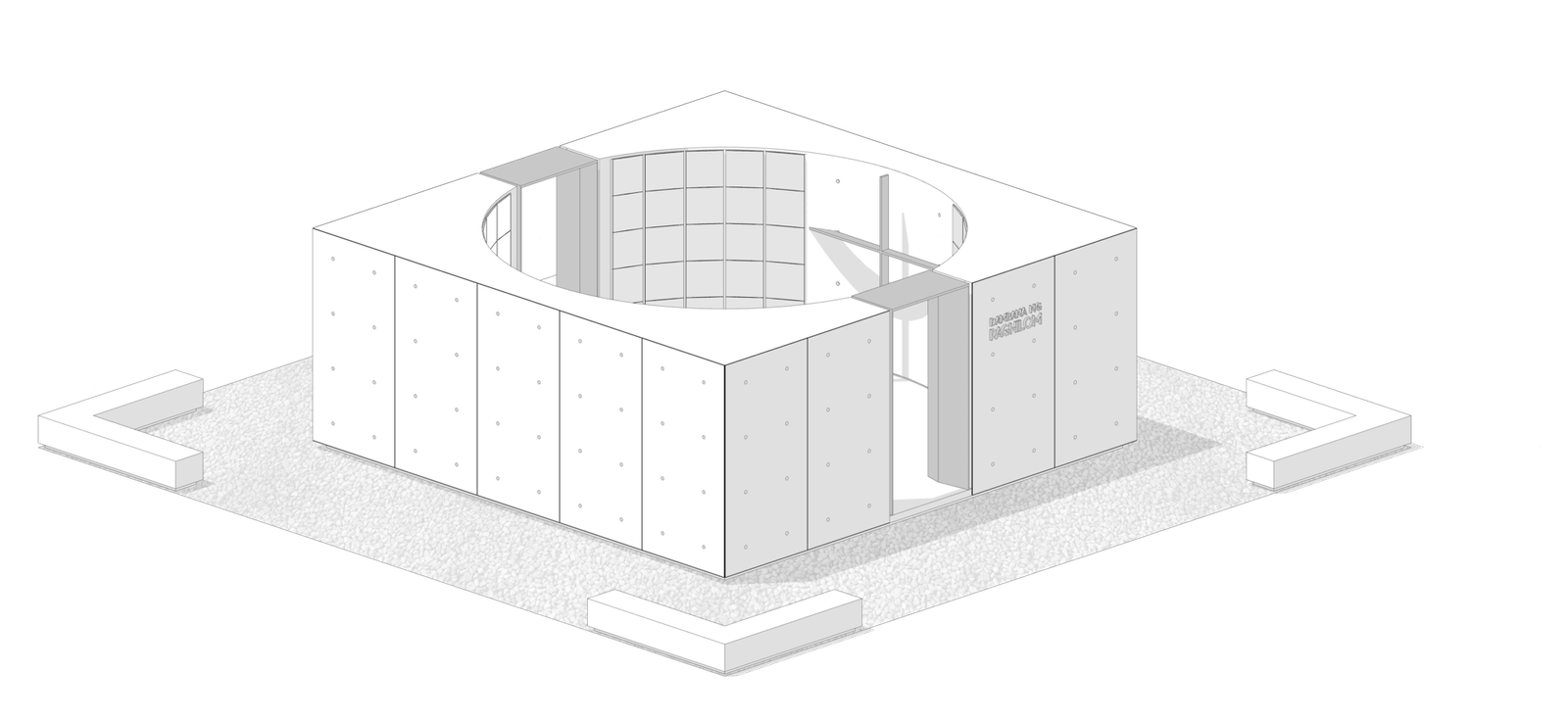

The resulting structure that emerged from the drawing boards of the Ortigas-based studio astounds with its spareness and lack of ceremony. It immediately stands out from the cemetery yard, a centrally located cubic volume that is monumental not in size but with its austerity and embrace of the elements.

The shape of soul

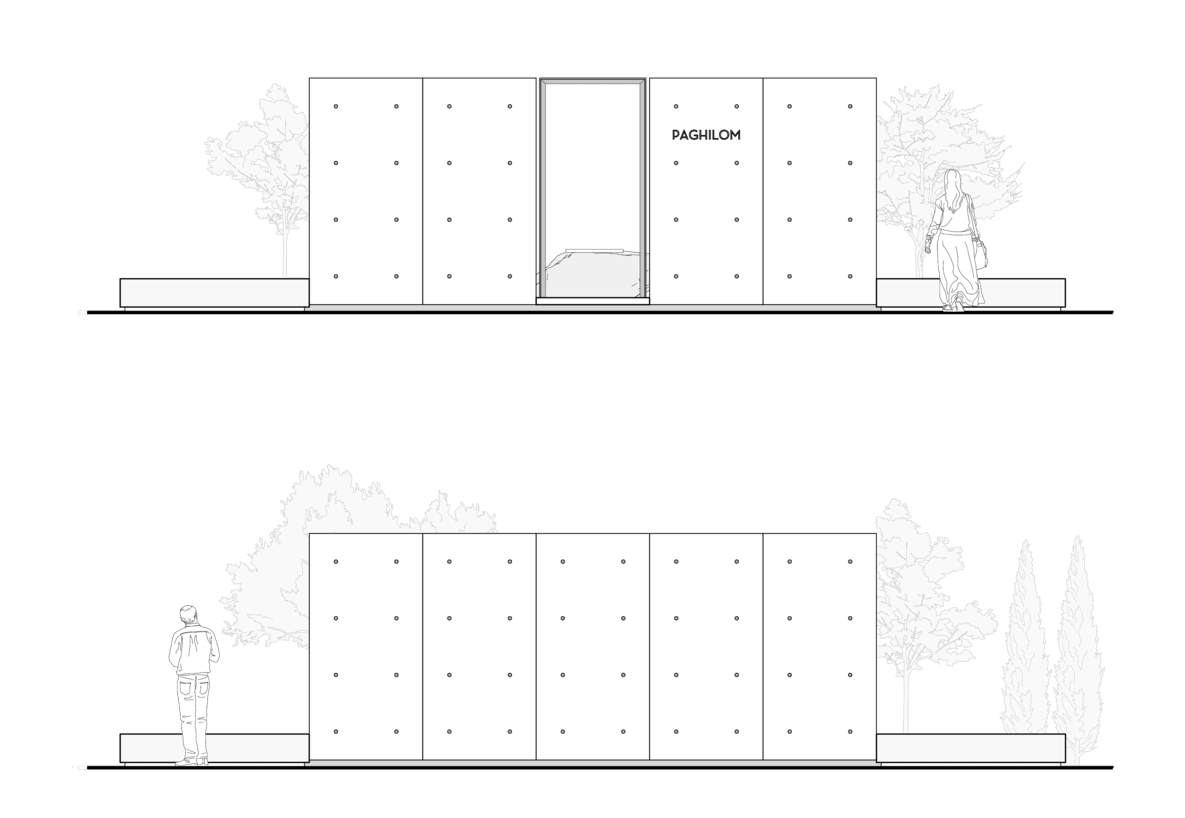

The approach to Dambana ng Paghilom is marked with discomfort, albeit one that is by design. Surrounding its smooth concrete walls are a bed of loose gravel one-inch deep, which, according to Nazareno is symbolic of the anguish and turmoil that burdened the dead and the bereaved. “The journey to healing is often an uncomfortable one,” the architect shares. Soon the audible crunch of the 2-meter-wide expanse of gravel underfoot gives way to smooth concrete. A blade-thin metal frame marks one’s entry into the space, a circular void that is at once limited and boundless.

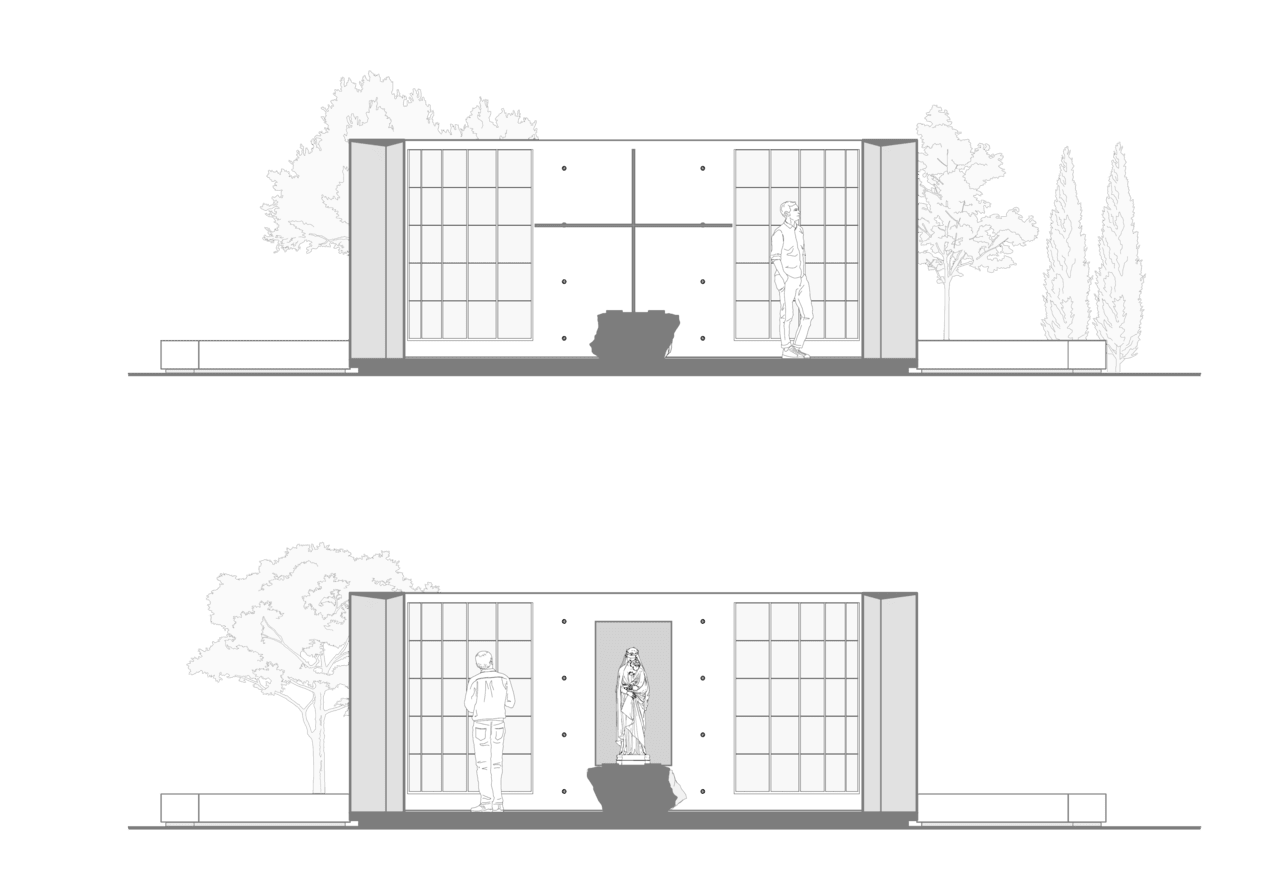

Dambana ng Paghilom is a cube with a cylindrical void at its heart, a geometric juxtaposition that is a response to its equilateral site, and an echo of the circular volume that once occupied its space. The volume measures six-meters wide on all sides, its 2.4-meter-high walls constructed from smooth, off-white concrete panels punctuated by two entry points. Within, a 5-meter-diameter cylinder is carved out, forming a void that stretches to the sky. “The decision to leave it open was deliberate,” says Nazareno. “There was initial pushback from our clients (The Arnold Janssen Kalinga Foundation Inc. founded by Father Flavie) regarding this move, but it was vital to our spatial narrative that it be kept open. The deaths of its occupants happened in darkness and secrecy. This space had to be the opposite and be a place of light and revelation.”

“What was most challenging about Dambana is it seeks to fill a void, to answer a need that cannot be truly answered by architecture. But we can help people remember.”

The memorial houses 100 niches, each designed to hold the remains of four to 25 individuals in 5-by-5 grids, providing a total capacity for 600 people. Each niche bears the names of its occupant, a reversal of the anonymity victims was once subjected to. The niches, also made of polished concrete, line the cylindrical inner walls and face a large rock lit aflame. An alcove with an icon of Mary, Mother of God, right across a 2.4-meter-tall metal cross complete the space.

Outside, the structure is framed by four corner benches outside, providing spaces for reflection and communal gathering. “Grief can isolate,” Nazareno shares. “We created this space to encourage people to sit together and find solace in shared experiences.”

Eternal flame

The stark architecture, from its simple geometries and spare material palette, quickly guide the visitor’s eye to three symbols within the circular void, that of the boulder, the cross, and the blindfolded icon of Mary, Mother of God.

A wind-battered striped boulder measuring a meter long holds court at the center of the memorial. “I wanted something heavy and raw at the heart of the space as an anchor,” Nazareno explains. Sourcing the boulder took longer than expected: it took the team six months to locate a specimen of the appropriate size, shape, and texture. A ‘tiger boulder’ with all the attributes Nazareno desired was eventually found in far-flung Marinduque by one of his go-to landscaping rock suppliers. “The rock was so heavy it cannot be carried into the site without machinery,” the architect recalls. The team then cored the boulder to host an eternal flame atop it. The flame is evocative of hope and how it continues to burn despite everything that threatens to snuff it, according to the architect. It was a poignant visual gesture slightly led down by technical limitations. The flame is manually lit daily by a caretaker.

The tandem of the blindfolded icon of a grieving Mary, facing the sheen and steely gaze of the cross provides mourners both a reality check and a promise of hope. In lieu of the usual luminous depictions of the Virgin, the rough-hewn icon portrays her in solidarity with the bereaved; Mary herself was once in a similar position, the mother of a son that was a victim of human cruelty.

For a memorial commissioned by a religious order, the sparse use of sacred imagery is surprising. It turns out that Nazareno and team wanted the space to be even more universal from the beginning: “I was initially unsure whether we needed extant religious imagery as it is a memorial that commemorates people from all walks of life and belief systems. At Father Flavie’s insistence, we added the icon and the cross. I think, in the end, the imagery of Mary and the cross further amplified the freeing and healing aspect of the space,” Nazareno reveals.

Politics of remembrance

The project naturally had its share of challenges; the conception and build according to Nazareno went largely hitch free (“We worked with a great contractor,” he shares). It was the intense gaze and the political and social commentary it would inevitably make that made all parties anxious. But Father Flavie remained undeterred, pushing the project forward, amidst a pandemic and during the closing chapter of the administration who set the bloody drug war in motion. It was a statement that bannered compassion over cruelty.

Nazareno originally wanted to keep the exterior walls of the memorial bare and unblemished, but the priest insisted on a small, illuminated signage, ensuring that the memorial’s purpose was unmistakable. The memorial opened with the inurnment of 11 EJK victims back in May 1, 2024, an emotional moment that saw hundreds of mourners, two senators and several foreign diplomats gather under intense media and police scrutiny.

Architecture of healing

Recently, Nazareno learned that architecture students from a university trekked all the way to Caloocan to study the Dambana ng Paghilom. “It’s unexpected, but humbling,” he says. Known usually for designing luxurious residences, he found this project to be an entirely different undertaking, one that helped him exercise maximum restraint, which in return led to a space brimming with meaning. “There’s a tendency to think architecture is all about form, grandeur, aesthetics, or creating a beautiful shell. But I think it is more about providing space that puts us in touch with our most authentic selves; providing a space to feel, to reflect… or in the case of Dambana, to grieve but also heal.”

Spaces shape experiences. They dictate how we move, how we feel, how we remember. For its architect, the miniscule footprint of Dambana far outscales the value the project had for him as he ponders his craft. “What was most challenging about Dambana is it seeks to fill a void, to answer a need that cannot be truly answered by architecture. But we can help people remember,” he pauses. “Because remembrance is also a form of justice.” •