Interview Patrick Kasingsing

Images OMA

Hi Chris! Welcome to Kanto! I really enjoyed your Benilde lecture, a survey of the work you’ve done for OMA thus far. Let’s start with something light. You have contributed to the design of some of OMA’s most recognizable buildings. What’s a project that has left a significant mark on you or your team? What was it that made the project noteworthy?

Chris van Duijn, Partner, OMA Asia: A lot of projects have come our way over the years. The significance of the projects varies depending on my involvement and growth over time. However, there are a few projects that are particularly significant to me. The first is my long-time involvement in Prada projects, which provided me with many opportunities as a designer. They wanted to do something very different in the world of retail and gave me a lot of time and resources to do so. This involvement has crystallized from designing shops to organizing events to eventually establishing Fondazione Prada. Fondazione Prada was my last project with Prada, as I later focused on Asia.

This project is probably the one that I have spent the most time on. The entire span of the project was 12 years. I remember arriving at the industrial compound on day one, not knowing whether it would become a project or not. However, at the end of it all, we completed a tower two years after the complex’s opening. The project’s lifespan is quite long, but working with art, artists, curators, creative clients, and existing buildings has been sensational. We went beyond the typical old-versus-new approach and defined a more reactive approach to working with existing structures.

It was quite an adventure, huh?

Definitely! Whenever I visited the site with new design ideas, I would see half-demolished and half-constructed buildings and get inspired to explore new design opportunities. It was an iterative process where we kept refining the design until we were satisfied with the result.

I consider my project with China Central Television (CCTV) professionally significant. We had very little time to complete it, and the project seemed structurally infeasible in many ways. Additionally, working in China was a unique experience, as the cultural differences were quite pronounced compared to my previous experiences.

Was the CCTV Tower OMA’s first project in China?

Yes. Before that, I mostly worked on US projects. So, working with CCTV was my first exposure to Asia and China, which was very different back then compared to today. It was a unique project that could have only happened at that particular moment in China. At no other place and time could such a project have been possible. It reflected their optimism during the early 2000s, with the advent of the Beijing Olympics; China sought to put its best foot forward as the world set its eyes on it.

Okay, you’ve touched on China and Asia and how cultural differences make working in the region a different ball game from the West. To clarify a few things, are you primarily stationed in Hong Kong and flying to the office in Rotterdam when necessary?

My role involves leading the Hong Kong office, which monitors all Asia projects. This requires me to travel frequently between Europe and Asia. Typically, I spend two weeks per month in each location.

Yikes, that sounds tiring!

Well, yes, but I find all this globe-trotting fascinating, and being based in Asia has been particularly enriching. A chance came up to take over the Hong Kong office, which I immediately pounced on. Having worked on projects like Prada and others in Europe, I noticed that they take much longer to complete due to a different mindset than in Asia.

In Europe and the US, projects are initially viewed as risky, requiring heavy risk management even before a single brick has been laid. I’ve learned about risk registers and risk managers in my project in Denmark, which has nothing to do with architecture. This approach makes projects take longer, based on what could go wrong.

On the other hand, in China and other parts of Asia, the approach is more optimistic. It’s about the opportunities available, often from a lack of experience. However, people are driven, and the client’s ambition and energy make the projects more enjoyable.

In Europe, people tend to view the glass as half-empty, while in Asia, people view it as half-full. This change in energy makes it more exciting to work on projects here. By the time I retire, I reckon I will have built three buildings in Europe and perhaps 30 in Asia.

Yes, things feel much more fast-paced here, for better or worse.

One of the reasons that motivated me to move is that Europe seems to be complete, in the sense that our cities feel fully developed. Therefore, there is only room for small-scale changes and adjustments in built-up areas. However, there is still a lot of construction and development in Asia. This allows for more opportunities to experiment with design and explore possibilities without being limited by urban constraints.

Right. And I think many architects from the West would probably say the same thing. That their most exciting or challenging work is located in Asia.

Now, OMA isn’t one to shy away from new frontiers, be it regional, theoretical, or spatial in nature. But with every leap of faith comes the possibility of failure or missteps. Winning the Pritzker also guarantees that the spotlight stays longer on the firm’s work, which opens it up more to criticism. So how does the firm, or you as an OMA partner, handle criticism or unsavory reviews regarding projects? Has major feedback led the firm to reevaluate or adjust its working ethos or design priorities?

Of course, you cannot satisfy everyone. I remember when we were working on the design and construction of the Seattle Public Library. During that period, we received the strange honor of being considered the most hated building in the United States. Many people opposed the construction of an American public building designed by a Dutch architect. They thought it would be too big, ugly, and unnecessary. However, after the building was completed and functioning as designed, it slowly became a local symbol of Seattle and is now embraced by the citizens.

As an architect, it is crucial to have confidence in your work. You must believe in your design solution and be willing to push for innovation and new ways of doing things. This may lead to projects that look different, weird, or provocative, but you must be firm in your convictions that your design is the best solution, or growth won’t happen. Achieving growth and innovation is never easy. Hopefully, with time, the public will come to appreciate and understand why we did things a certain way. You have seen in the lecture that what you may initially perceive as crazy, aimless geometry isn’t so fanciful once you know the back story.

One significant difference between the past and present is the rise of social media. Nowadays, we can read news articles online and view comments from readers. However, it’s not always wise to read comments, primarily when a new project is published. You’ll often find that most comments are negative. This is because people who object to something are usually the ones who are the loudest. They want to be heard and to have their opinion heard by others. We are, of course, receptive to feedback. Still, I think the public should also understand that whatever is getting built is the product of days, months, and years spent by the team simmering on things to arrive at what we perceive is the best solution for stakeholders, them included.

“As an architect, it is crucial to have confidence in your work. You must believe in your design solution and be willing to push for innovation and new ways of doing things. This may lead to projects that look different, weird, or provocative, but you must be firm in your convictions that your design is the best solution, or growth won’t happen.”

C H R I S V A N D U I J N

We touched on the public sphere in the previous question, so let’s talk about public realms and spaces, a typology big on the OMA agenda. Specifically, I would like to know how your office translates this typology in the Asian context and what the differences are in how it is perceived, received, and applied in comparison to the West. Lastly, I’m interested in knowing what challenges and nuances your Hong Kong studio has faced while introducing open spaces in a region filled with densely populated cities.

Architecture, as a profession, traditionally followed a public agenda. However, with the privatization of nearly everything, the public agenda is now mostly dead and buried. Even public spaces are often privatized. For instance, in BGC, there is a large outdoor shopping area that feels public but is actually 100 percent privately owned.

What I find exemplary about our work is the overlapping nature of architecture and urbanism. Many of our architectural projects have significant urban components, while our urban projects are highly architectural in their approach. This can manifest physically, such as creating open spaces or engaging with the surrounding environment.

I presented a project in Hangzhou [Hangzhou Prism] during my lecture. The development was entirely private, and the initial plan was to construct two towers with drop-offs and a car park. However, the proposal was to create a sheltered outdoor space at the center of the project, which would be positioned at the end of a commercial retail street.

So basically, what has been offered to the city is a space that can be used for various events. For instance, it can be used as a sheltered and dry space with good acoustics for Christmas markets during Christmas. Additionally, this space can be used for other types of small markets and festivals. This is something that the client did not initially ask for as they were worried and scared about the uncertainty such a space brings. But then they saw how the city responded enthusiastically to the space provided them, and they have since become a stakeholder in the project. That’s amazing. And it’s still a 100 percent private public space.

Every project has multiple stakeholders involved. There is a client who develops the project, a user who will eventually use the project, and the people living nearby who will be affected by the project daily. We strive to create projects that benefit everyone involved. This is how we work towards incorporating public welfare in otherwise private projects.

If a developer who took a risk has succeeded, other developers would be more inclined to do the same. We can only benefit from more developers with visionary mindsets.

Now, let’s shift the topic back to working in Asia. You have been overseeing the Hong Kong office since 2015. Asia is a region brimming with distinctive and myriad cultural expressions. How does OMA ensure its works aren’t caricatures or pastiches of regional traditions and customs? Like the penchant of some architects to supersize a regional costume or object to architectural proportions. Let us in on how you collaborate or have worked with local architects to bring Asian projects to fruition.

It starts with being genuinely interested in the place you need to work in. Yes, it sounds very basic, but it’s crucial. That means you must make an effort to understand your ‘workplace.’ You should visit the site, talk to people, and get a feel for the place. You’ll be surprised how many globally renowned firms don’t bother with preliminary site visits. You should also see who else, besides your team, could be a partner in this project. You could invite them as consultants or critics during the design process.

When we started working on the CCTV Building project in China, we collaborated with Chinese architects who visited us regularly in Rotterdam or during our presentations. They provided feedback to ensure we made no mistakes or cultural faux pas. Additionally, they helped us discover exciting elements we could integrate in a contemporary way or on a different scale.

It’s essential to invest in the place you work. This means truly understanding the culture and doing more than just basic research. Don’t rely on convenient local or cultural icons for design, but strive to understand the sensibilities and qualities of the community’s culture and spaces. Projects become great when there are multiple levels of connection, going beyond the symbolic or visual details. As an international firm, we aren’t asked for vernacular projects, but this should not be an excuse to create something that doesn’t belong to the community. And that’s also why we’re organized this way: a global office with a regional focus. It’s all about finding the right balance.

A follow-up question on architects of record. Do you get to pick who you want to work with locally? Or are they usually predetermined by your client?

It depends on the project. Ideally, we propose and select the local architect to work with us. However, sometimes, our clients already have an ongoing relationship with a local architect. In Korea, local architects are our clients, and they work as delegated clients. This is the typical setup. We are interested in finding local partners to complement our work so that we’re not in competition or completely detached.

Okay, I ask because I am aware of this OMA-attributed hospitality project in Bali called Potato Head Studios, which your office worked on with renowned Indonesian architect Andra Matin.

Ah, yes, I am familiar with this project.

However, would you know what the dynamics were like in these cases? Like, who gets to call the shots?

Each project team member brings a unique contribution to a project; collaboration is at the heart of our company’s DNA. This applies both within our office and outside of it. When I started working at OMA, Rem led a team of just 35 people. Now, we have 350 employees and eight partners across three global offices (Rotterdam, Hong Kong, and New York).

Rem always uses the word “we” when explaining projects, which is significant. It demonstrates his belief in group dynamics and how everyone, from interns to partners, plays a role in the creative process. Rem and us partners make the final decision at the end of the day, but every project is a collective effort. It’s an innovative environment where ideas are bounced around and developed collaboratively, not a single person dictating from the top down.

So, you would say, like with the partners and Rem, the hierarchy is flat?

Yes, we are eight partners, each with an equal stake in the company. We all have our clients and part of the office, but nobody controls everything. As a collaborative network, we work with the best local and international specialists to learn from them and involve them in our work. I believe that it’s a great experience for everyone involved because the learning is democratic and collaborative instead of prescriptive and dictatorial.

I see.

We have a collective ownership structure that sets us apart from our peers. Unlike most design offices, which are centrally organized and run by a few partners, we distribute our ownership and operations across three design offices around the world. Although I’m not actively involved in the New York office, for example, I’m confident it is being ably led, and, as a partner, I stay informed about its projects.

Right. Adopting a decentralized system can be helpful in this regard because it allows for greater flexibility and adaptability. The decentralized approach ensures that everyone is on their toes and ready to tackle challenges in any location.

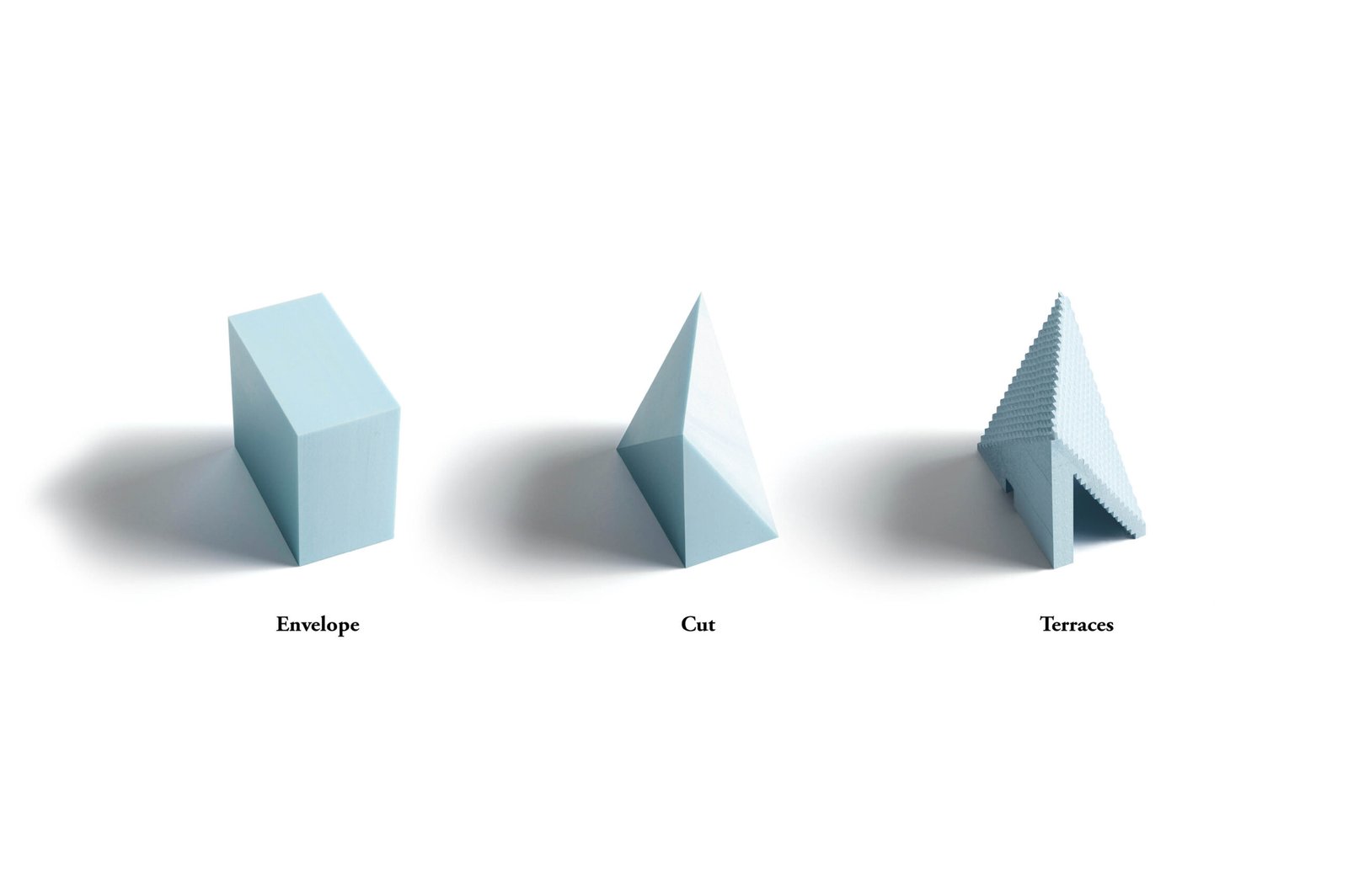

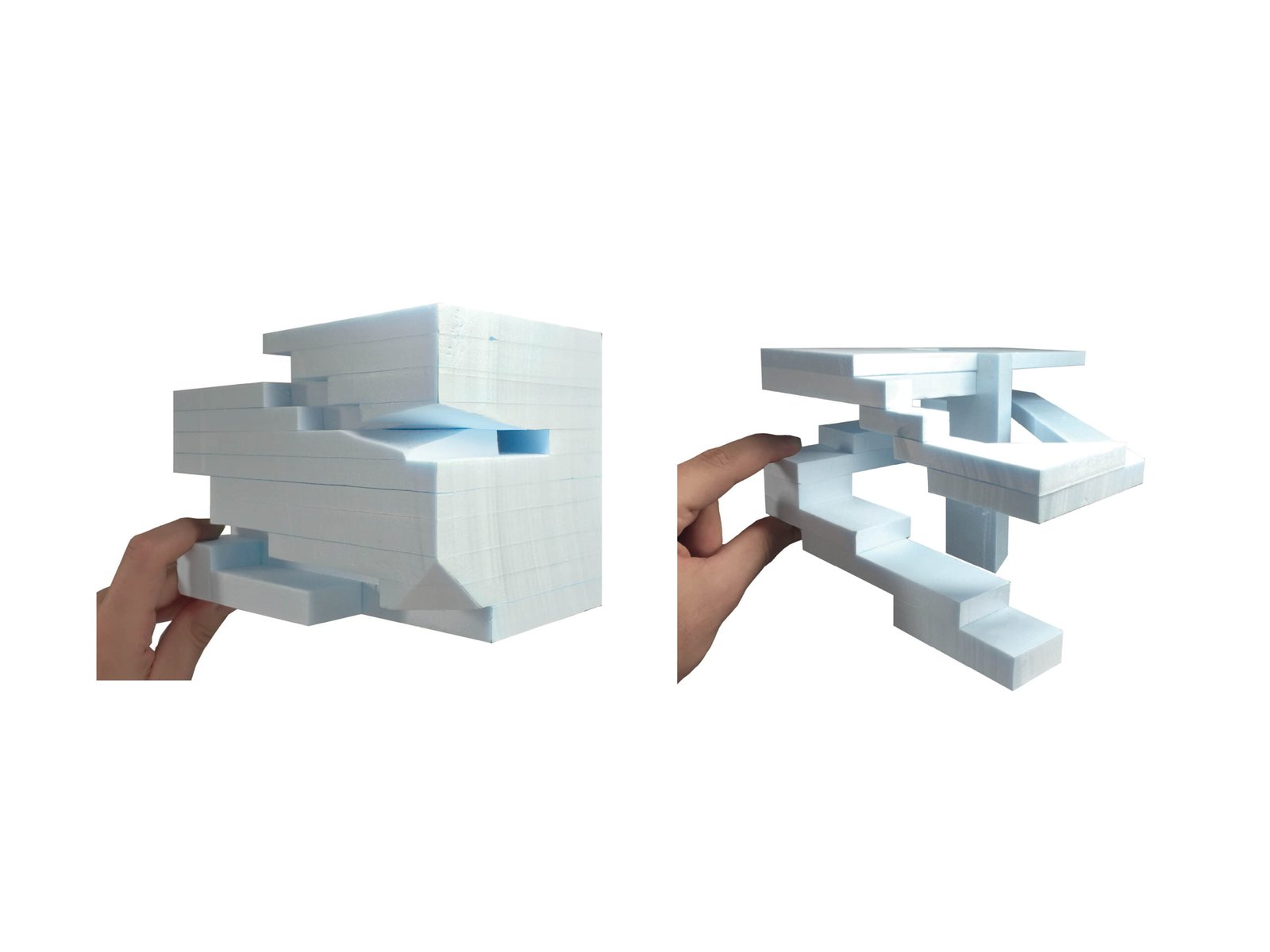

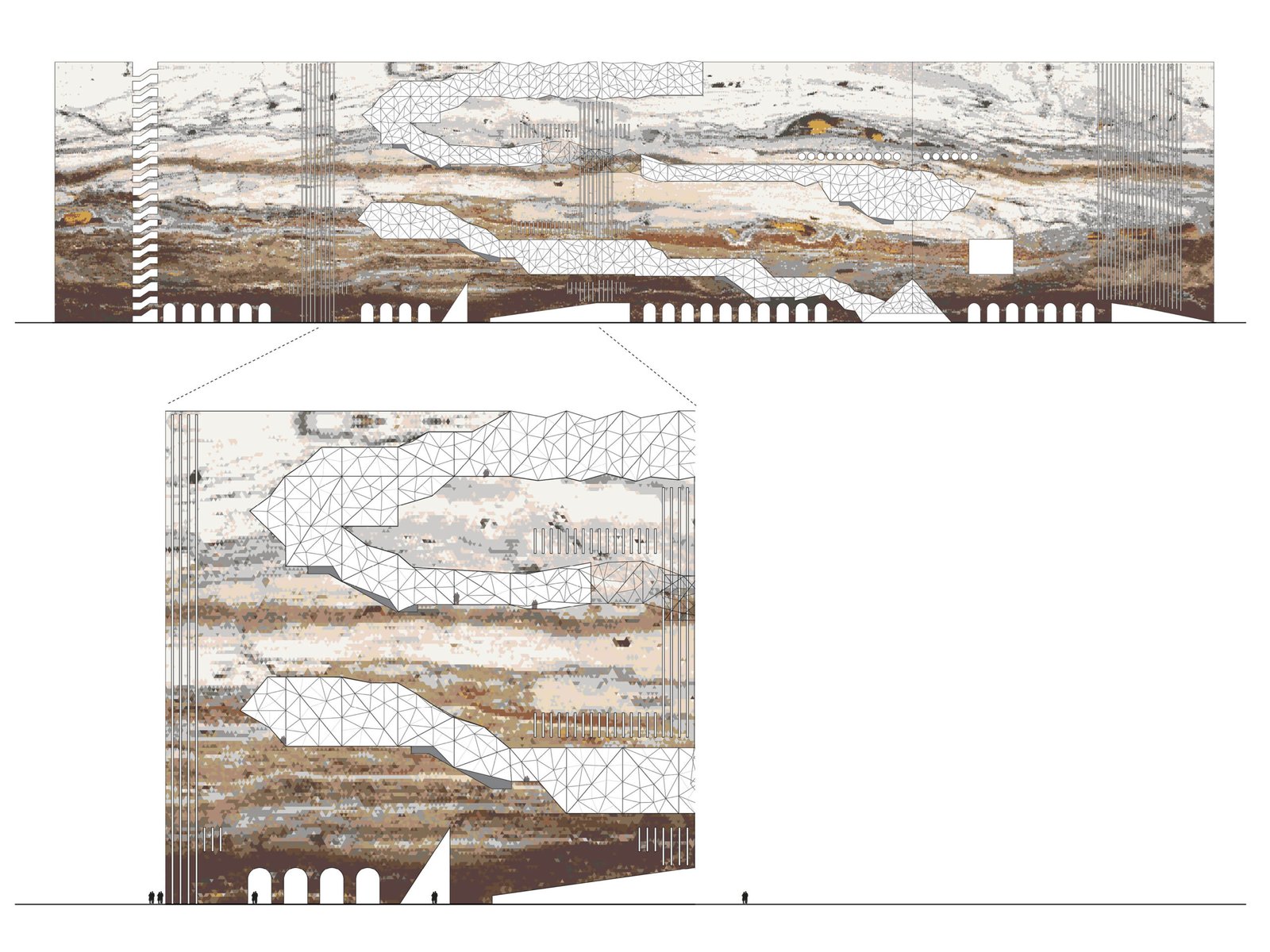

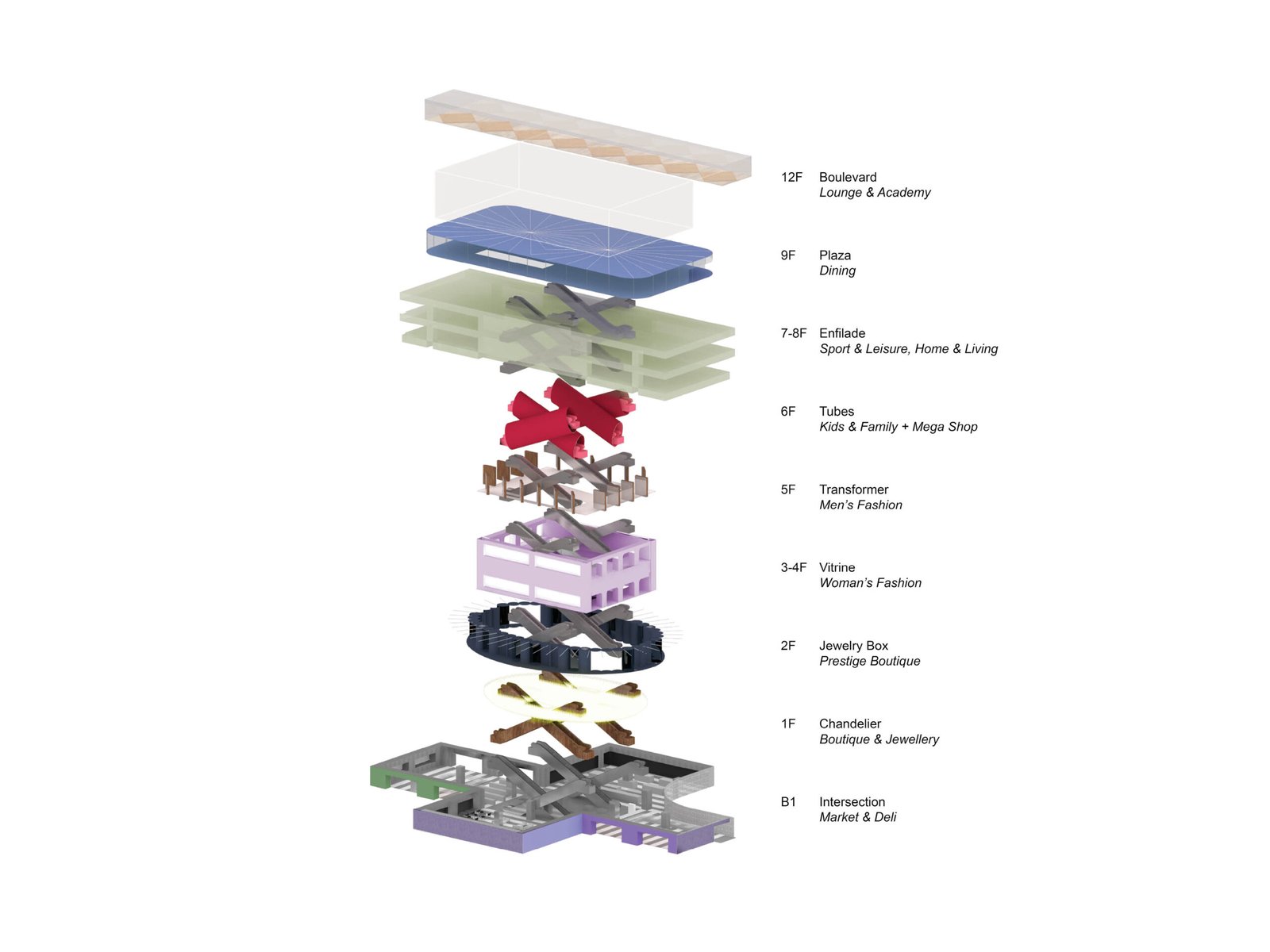

Yes, we have become highly versatile, so we can easily change direction if the project requires it. It also liberates us from predictability. For instance, some of our people questioned whether our approach was right during the Galleria project in Seoul. However, it was an important project as it helped us move away from predictability and reinvent ourselves. This ability to make quick pivots in response to a project’s effectiveness or heightened potential has allowed us to take big steps forward.

It’s funny that you mentioned the initial uncertainty surrounding the Galleria. I was unsure how to regard it myself when it finally made the rounds of social media and design websites in 2021. I have now decided that I love the project, not because it is conventionally attractive; it toes the line between beauty and ugliness with its texturality and visual excess. I can’t help but admire the audacity of it all. There’s so much to take in, but formally, also little, as everything is primarily confined within a box. Speaking of boxes, you have made your rounds of Manila, and I’m sure you’ve noticed that many of our malls are dull boxes.

(Laughs) Yes, there are a lot of boxes with trimmings here and there. Regarding the Galleria project, it was a significant move for us as the Galleria had a very conservative clientele. In the lecture, I mentioned how the CEO and the owner behind our retail client had differing visions, so we decided to think both inside and outside the box. Straddling that fine line, as you said, yielded something exciting and new, not conventionally attractive but also strangely magnetic. The Galleria project has become a reason for other clients to engage us as they acknowledge our capabilities based on our work. Retail is a fickle, fast-changing industry, and what we are doing now will be outdated in 10 years.

Right. As you’ve unpacked in the lecture, OMA and AMO have done all sorts of things. You’ve done master plans, you’ve done malls, you’ve done fashion shows. Has there been a project typology that has eluded you or OMA’s grasp? Why would you want to work on this project typology?

Okay, so whether it’s a football stadium, an airport building, a hospital, or a data center, we are interested in taking on the project. We believe we can contribute to any project, even if it’s something we haven’t done before, like an airport or something utilitarian, like a data center. However, clients usually prefer to work with someone with prior experience in their field. Hence, we always try to expand and explore new markets to gain experience and expertise. In some cases, we turn traditional typologies on their heads if it means a better design solution…

Ah yes, like that Transformers-inspired opera house entry! That was mind-blowing!

Yes, but since we had the luxury of resources for that entry, we are willing to push the limits of what design could do to meet the client’s steep requirements.

We have designed performance venues, both built and unbuilt. However, once we have completed a project, we move on to something else. We don’t repeat ourselves. In that sense, we are very idealistic and perhaps a bit naïve. We don’t recycle much of our material and treat each project as distinctive problems and opportunities with very specific solutions. In that way, we don’t ascribe to a formula.

Well, architects must be resolutely naïve and idealistic. Otherwise, you won’t survive, and the quality of our spaces won’t progress.

Right. Right.

Let’s wrap up this interview by revisiting OMA’s origins. Founder Rem Koolhaas built his reputation on knowledge sharing through his literature on architecture and urban planning. OMA has contributed significantly to architectural discourse through publications and theoretical case studies that are sometimes required reading for architecture schools. Knowing this, how do you see the firm’s role in shaping the intellectual landscape of architecture? What impact do you hope OMA’s ideas will have on future generations of architects?

The office’s first 20 years were built on the reputation of unbuilt projects. It was based on theory and manifestos because, at that moment, there was very little work for architects. It was almost a necessity to reflect on the profession. After that came the roaring 90s, when the industry globally exploded, especially in Holland and Europe. Those were the golden years, and the good thing was that the industry became more global. It used to be dominated by a couple of Euro-US-based companies of old men who had been in the industry for a long time – Eisenman, Gehry, Meier, and names like that. Then suddenly, an avalanche of new young companies emerged, initially in Europe and Holland.

That trend has continued, and when we started in China in 2002 and 2003, there were no design offices – only design institutes with up to 1,000 to 2,000 people in architecture and engineering, but they were very bureaucratic machines. There was no culture of boutique Chinese architecture communities and no contemporary Chinese architecture period. However, in the first two decades of the century, there has been a significant opening and growth in China, expanding and offering a lot to learn, see, and enjoy, like in other countries.

We have observed significant growth in the architectural industry spreading to countries like Vietnam, Thailand, and many others. However, this growth has caused architects to work quickly to meet the increasing demand. This phenomenon has resulted in instant architecture, which involves using formulas or repeating popular designs that people find appealing or ‘Instagrammable.’

Architects have had limited time for reflection, but we were fortunate to invest time in creating AMO early on. This allowed us to reflect on our knowledge and actions through exhibitions or publications. This need to reflect has been historically urgent for architects and has helped us test and improve what we do. It also allows us to determine whether architecture is the best solution to a problem or requires a different discipline or platform, which is why AMO is multidisciplinary.

I appreciate how you emphasize the importance of zooming out of architecture to see the bigger picture. I was reminded of the quote you mentioned earlier about architecture being a medium rather than a means to an end. Architecture exists in the context of many other things and needs to transcend beyond just being architecture.

Yes, we mustn’t scrimp on the time to reflect and to think. We shouldn’t just build, build, and build, but think, build, and reflect. Despite the overproduction of architecture nowadays, the theoretical realm and study of it have been reduced. It is always beneficial to take a step back and reflect on what we are doing right and what else we could do. We need to understand our place in the universe and how vast it is. This knowledge helps us to drive our agenda of creating responsive and evocative spaces for people. We will continue to pursue this agenda for as long as we can, however we can.

Thank you for your time, Chris! •

2 Responses