Interview Patrick Kasingsing

Images Batad Kadangyan Ethnic Lodges Project

Hello, Raymond! Welcome to Kanto! In celebration of fifteen years of supporting the Batad community through adaptive reuse of ethnic baluys (ancestral hut), your team at the Batad Kadangyan Ethnic Lodges Project is inviting the public to participate in a one-of-a-kind Pahang, an Indigenous Ifugao house blessing ritual presided over by the last mumba’ih (shaman) of Batad. But before we get to that, let us recall your first encounter with the ritual and the baluys. What was it like? And can you run us through the generalities of a Pahang?

Raymond Macapagal, Assistant Professor at UP Diliman: I first visited Batad in late 2005 and immediately fell in love with the landscape. I returned a few months later and requested to stay in a baluy, which is the traditional house of the Ifugao. I was then led to Ramon’s Homestay, where the owner (Ramon Binalit), had me stay in his tiny ancestral hut. It was warm and smoky inside since it had a cooking hearth. It was also filled with all sorts of traditional items like heirloom rice wine jars, carved wooden spoons, a ritual box, and decorated with the skulls of sacrificed animals. Seeing my great interest in the house, my guide (Pio Mannod) proposed an offer I couldn’t resist: if I help his family restore their dilapidated baluy, then they will give me the house! As I did not really intend to own a house in the village, I just made a better counter-proposal: I will help them adaptively restore their baluy, and they can host tourists so that they have extra income. They happily agreed.

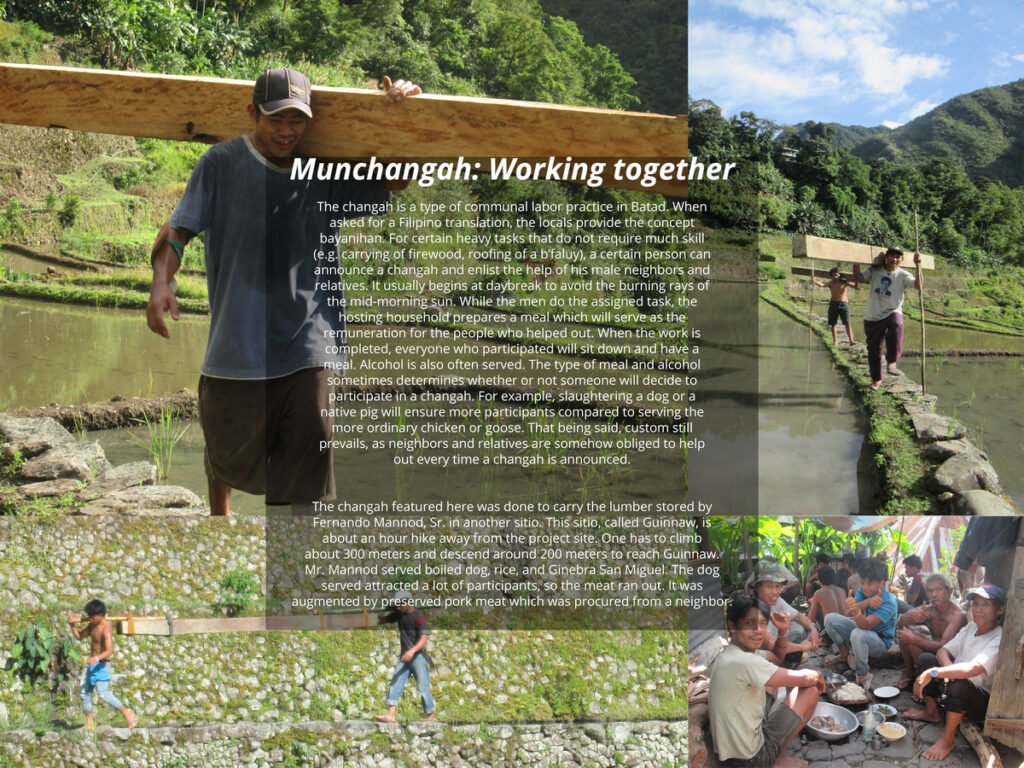

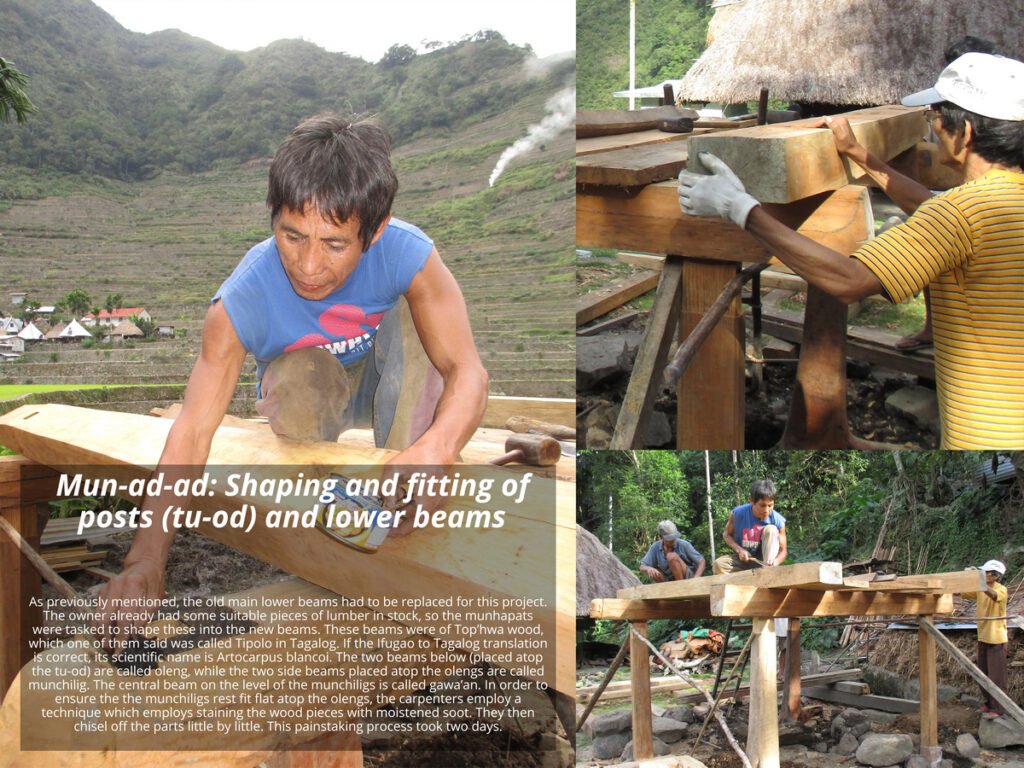

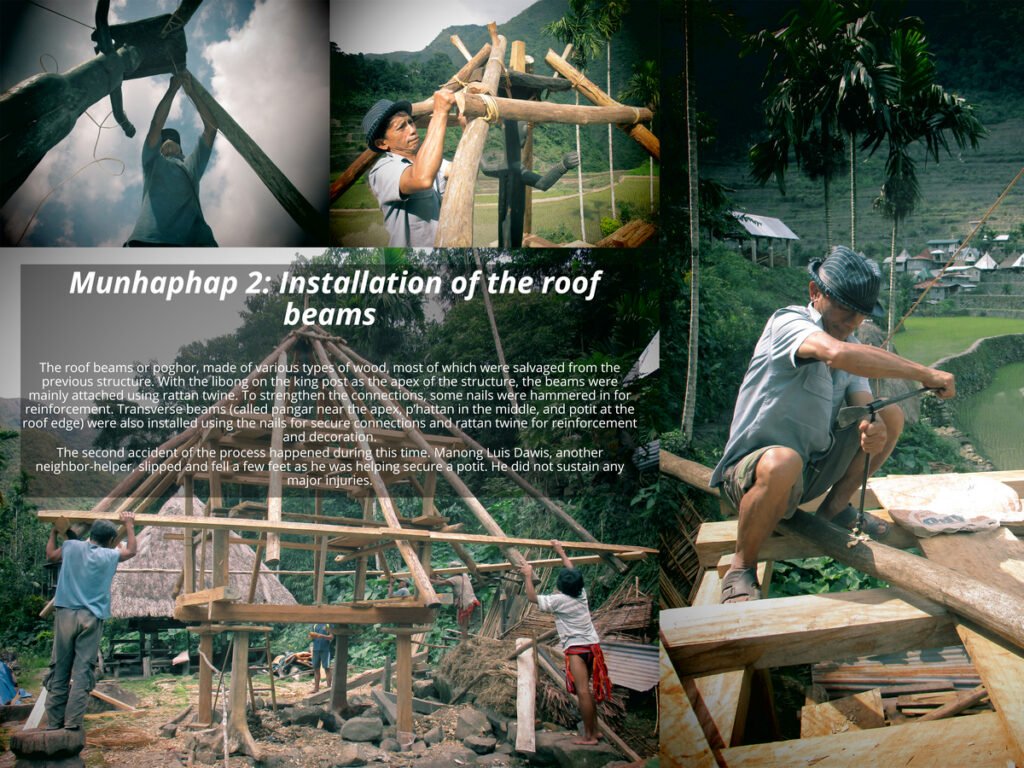

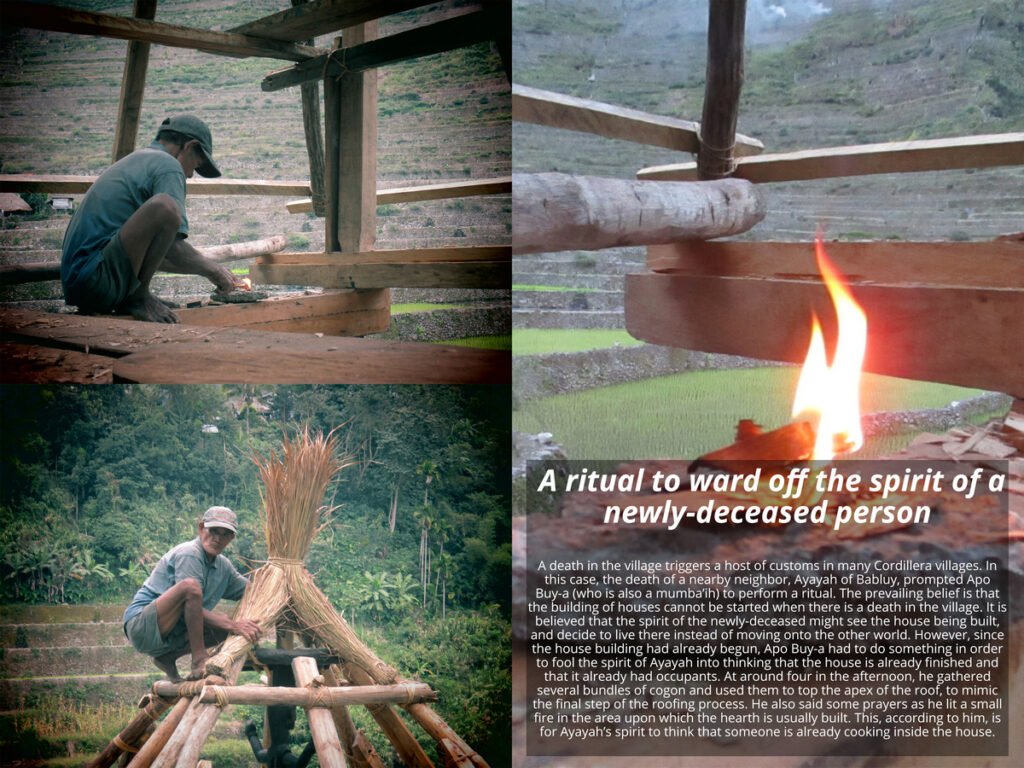

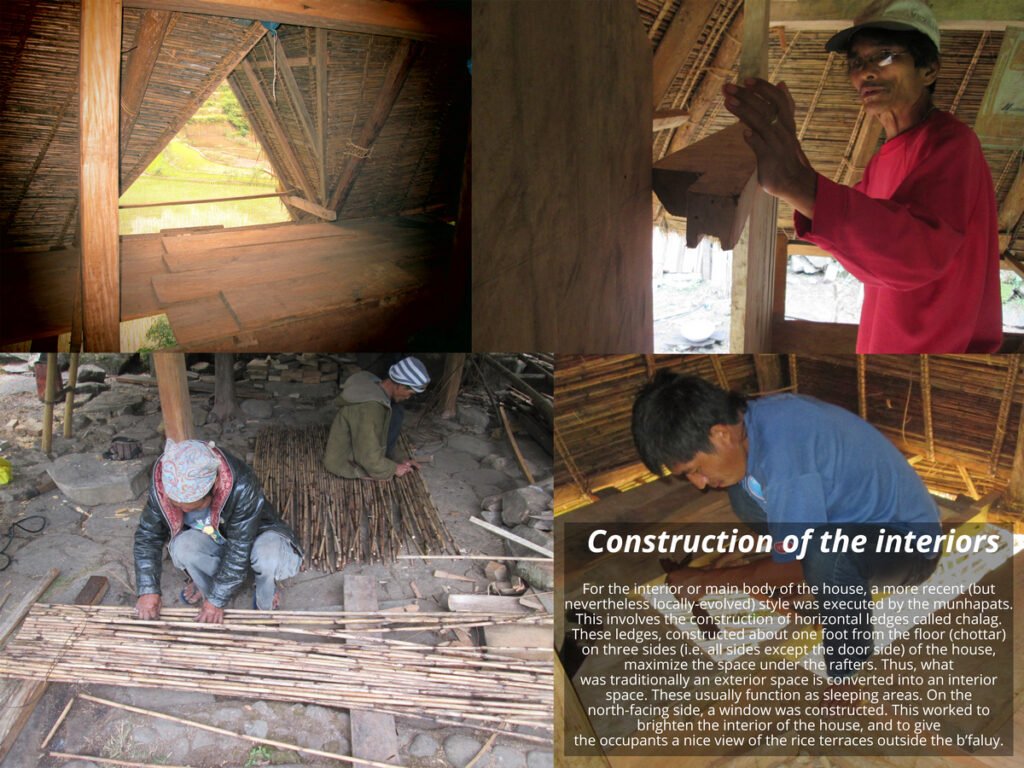

The house was restored with some funding from me (to buy materials that cannot be locally sourced), while the Mannod family provided building materials from their woodlots and manual labor. The work was done using the changah system, their version of bayanihan. My best friend, Raoul Bermejo followed suit and helped the Ambojnon family restore a larger baluy.

To inaugurate the houses, we did a Pahang or house blessing ritual officiated by five mumba’ih (shaman). It starts before sunrise, as the shamans call upon the ancestors to join the festivities through a recitation of their genealogy. Then the shamans perform other prayers interspersed with dances as they recount the stories of their people. It was a ritual filled with chanting, dancing, gong-playing, wine-drinking, and the slaughter of three pigs. We cooked lunch and shared the meat with the community and a few tourists.

In your studies of indigenous communities around the Philippines, what makes the ritual distinctive and a must-see? Do other indigenous communities you’ve encountered have equivalent rituals?

I have not witnessed other rituals as grand as this in other places in the Philippines. This is a must-see not because there is something distinctive about it. Many other indigenous communities have similar rituals to inaugurate a house. However, this ritual is a dying practice, as many communities have lost their old ways of worship due to the influence of foreign religions like Christianity.

Was there a particular moment that convinced you that helping preserve the community’s traditions and uplifting their livelihood was going to become your advocacy? Was the community immediately on board with expanding the Ethnic Lodges initiative?

What cemented my decision to help stems from the main complaint of the rice terrace farmers: despite the influx of tourists into the village and the terraces, it was only the tour operators, guides, and inn owners who benefited most from the tourist money. The very people who tend the terraces hardly reap the benefits!

As previously mentioned, it was actually the people in the community who proposed this. So, in most cases, the success of a restoration project was ensured. We have been able to restore at least 12 houses all over the village.

What were some of the challenges you’ve encountered with the initiative? What steps were taken to ensure that the resulting adapted structures stay true to the community’s roots and traditions?

It has happened that some families were not able to complete their restoration projects because of various reasons. We also ran into difficulties sourcing certain materials like mountain grass, as many cogonal areas in the village had been converted into vegetable plantations or reclaimed by the forest. We have learned to be more selective of our partners, and also to ensure the availability of materials before doing a restoration. It was also very important for us to involve the traditional carpenters who have the knowledge and ability to construct these houses, as they are built differently from typical houses.

What do you find distinctive about the baluys? How were the structures compatible with adaptive reuse as dwellings? What were the challenges in adapting them as tourist accommodations?

I think they’re perfect examples of environmentally-responsive vernacular architecture. It is raised from the ground to keep away from pests and enemies. It even has wooden disks on its posts to prevent rats from scurrying up. The thick cogon grass roof keeps the interiors cool in the midday sun and warm at night. You also won’t hear the noisy pitter-patter of raindrops during downpours. The wooden walls also help to maintain a relatively constant temperature, which is important to prevent the growth of fungi that damage the rice crop stored in the attic of the house. This is also the most widespread type of house that still exists in the Philippine Cordilleras. While the traditional houses of the other indigenous groups in these mountains have all but disappeared, the Ifugao baluy/b’faluy/fale continues to exist!

The biggest change we made in converting the baluy into tourist lodging is the addition of windows. This provided much-needed light and a pretty view of the terraces. However, we had to devise a way to prevent water leaks in the joints of the window frame. That made me understand the reason why these houses did not traditionally have windows: they had to be watertight. More open-minded tourists loved this experience of living in a baluy. Of course, they had to contend with the fact that there are minor inconveniences like bugs. But it was an interesting and unique experience that one can learn so much from.

What were some of the tangible or extant benefits that you’ve seen as a result of this initiative? Were there unforeseen cons?

The increased demand for baluy lodging also encouraged other standard inns in the village to build their own baluys for their guests. Other outsiders also started working with the locals to restore more houses. However, tourism totally evaporated during the pandemic, and some of the restored houses fell into disrepair. We are hoping that tourism recovery will bring in more interest in funding house restorations.

Why is it vital that we preserve intangible heritage such as the Pahang ritual?

This ritual is our spiritual connection to our ancestors. Imagine doing a roll-call of ALL your ancestors to join in this ritual feast. This form of ancestral veneration is a unique characteristic of indigenous religions here in the Philippines and is hardly seen in colonial religions like Christianity. It reminds us of who we are, and where we came from.

You are currently inviting the public to join a special Pahang ritual. What do you want participants to get out of the experience? Are there other means for the general public to help support the community?

As there is only one remaining mumba’ih in Batad, this might be the last opportunity for us to witness a ritual such as this. That is why we are doing this. Moreover, we want the participants to experience community-based tourism that is rooted deeply in indigenous heritage. Beyond the communal feasting of the Pahang ritual, guests can also participate and learn about the various aspects of Batad Ifugao life.

The Ethnic Lodges program has been running for fifteen years. Any interesting or memorable anecdotes from both participants and the partner community about the initiative?

Interestingly enough, I think the most significant story of this project does not have anything to do with tourism. Several years ago, an elderly woman from the village, Auntie Imbang, asked us for help in restoring their baluy. She said that, even though they had a “modern” house, she and her husband Uncle Lamagon still preferred to live in their old baluy even though it was about to collapse already. This made us realize that baluy restoration should not only be done for tourism. It should also be done so that the locals can continue living as they used to for the past few centuries.

Also, my greatest sense of accomplishment comes from my students at UP Diliman, whom I’ve brought on study trips to learn about the rice culture and the traditional houses. Many of them still message or tag me on Facebook once in a while saying that their Batad trip was their best field trip in college.

Are there future projects under the Batad Kadangyan Ethnic Lodges initiative you’d like to share with our readers?

We are hoping that some people may be able to pitch in and help restore several baluys that fell into disrepair during the pandemic years. We can connect you with the families and help manage your own baluy restoration project in Batad!

Also, harvest time is fast approaching. It would be great if we can also arrange a harvest tour of Batad in the coming months. •

Invitation to a House Blessing Ritual in Batad

The Pahang house blessing ritual in Batad will be held on the morning of 14 May 2023, at the Mannod and Ambojnon baluys in Sitio Balihong, Batad, Ifugao. People wishing to join may contact Raymond Macapagal at 09368678974 so that he can connect you with a local Batad guide. Support and cooperation for future restoration projects are also very welcome. More information about the house restorations may be found on their Facebook page: Batad Kadangyan Ethnic Lodges Project.

2 Responses

Amazing article – and a great partnership! I wish the project well! Here’s to preserving culture while sharing and educating about it!