Words Joey Manalo

It must be so difficult to be a painter of figurative subjects today; to create something “original” with thousands of years’ worth of art history and crowded with countless masters and geniuses before us. It is challenging if one is conscious of the weight of the past, but once a painter reconciles these worries, it is a rewarding feeling.

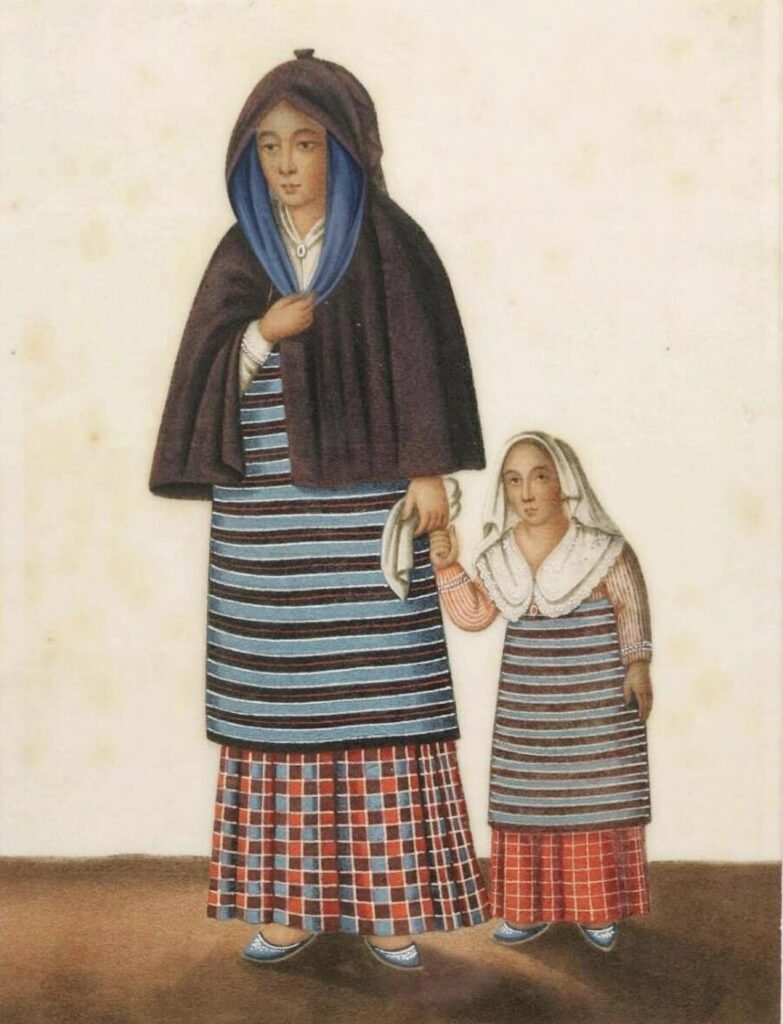

In this Lyra Garcellano work entitled “Casta V: After Domingo’s An Indio Woman Going to Mass with a Little Girl”, with an unassuming and almost mild color palette, we still effectively get the necessary daily dose of wisdom to give us the boost in going about our daily lives. We can appreciate a painting that resists merely stylized versions of something else. More relevantly, the subject in this work warrants a more detailed probe into the political and cultural climate of the early 19th-century Philippines. The subject here references one of Damian Domingo’s tipos del pais or “types of country”.

Revisiting Tipos del Pais

For those whose memory needs refreshing, Domingo’s tipos del pais, according to Wikipedia, is “a style of watercolor painting that shows the different types of inhabitants in the Philippines in their different native costumes that show their social status and occupation during colonial times”.

Damian Domingo is a high figure in Philippine art history especially during colonial times, over half a century before the time of Rizal, Luna, and Hidalgo. A lot of sources debate Domingo’s ethnic background— was he a mestizo de sangley (Chinese mestizo) or a mestizo natural (native mestizo)? I have no answer for this now but it made me realize that the fact that many essays and books dwell on this subject only confirms the unending obsession with race and class in the Philippines. How do we further understand the irrationality of race classifications imposed by colonialism and the baggage they left behind? It’s hard to believe that if you were born in the Iberian Peninsula (There was a time when the crown of Portugal was united with the crown of Spain but in a strange way. This topic is for another time) and living in the Philippines, you were exempted from paying taxes. In Philippine history class at school, we learned about the “peninsulares” and “insulares” etc. but I don’t recall learning much about the Napoleonic wars happening in Spain and the rest of Europe (coincidentally this was during Damian Domingo’s time as well) which is a shame because further examining gives insight into the failure of the “empire” concept and its inevitable doom.

The same goes for the simultaneous revolutions that happened all over Latin America during the early to the mid-19th century. History as an epic saga, a drama series, is strangely entertaining and rewarding. I must admit the guilty pleasure of approaching history from an encyclopedic perspective as well as a critical one—the appetite for history and it being a source of pure pleasure.

Going back to Damian Domingo’s period in the Philippines, social prestige and economic ascendancy were relatively new concepts. During this time, the Manila Galleon trade was now wrapping up after over 2 centuries, and for the first time the Philippines was treated by Spain as a direct colony (previously we were just a province of a colony, and the actual colony was New Spain or present-day Mexico had just gained independence during the early 19th century as well). While the local economy was starting to flourish (while not inclusively), it did give opportunities to some such as Damian Domingo, to flex their artistic muscle.

In this small oil on ivory work, we see someone who seems to be more interested in looking like a soldier than an artist. Let’s also not forget that Damian Domingo founded the first independent art academy in the Philippines and championed artists in a time when “art” was inseparable from the church, so I guess this warrants his preference to be portrayed as a five-star general. It is also interesting that miniature portraits during this time were generally reserved for Christ, Virgin Mary, or the Saints. Even the “agimat” was miniature-sized. These were protected in lockets and shrined in cases meant to withstand the disaster-prone environment.

Referencing Tipos del Pais

Una Yndia que va a Misa con Chiquita, translated roughly to “An Indya who goes to mass with a little girl”, is a curious choice for Lyra to reference among the Tipos del Pais. It depicts Damian Domingo’s wife and one of their daughters.

I honestly found it to be creepy at first because of the blackened unrecognizable faces, but it has officially grown on me and blossomed from something that has a feel of a gorgeously illustrated tapestry as opposed to something philosophical and heavy.

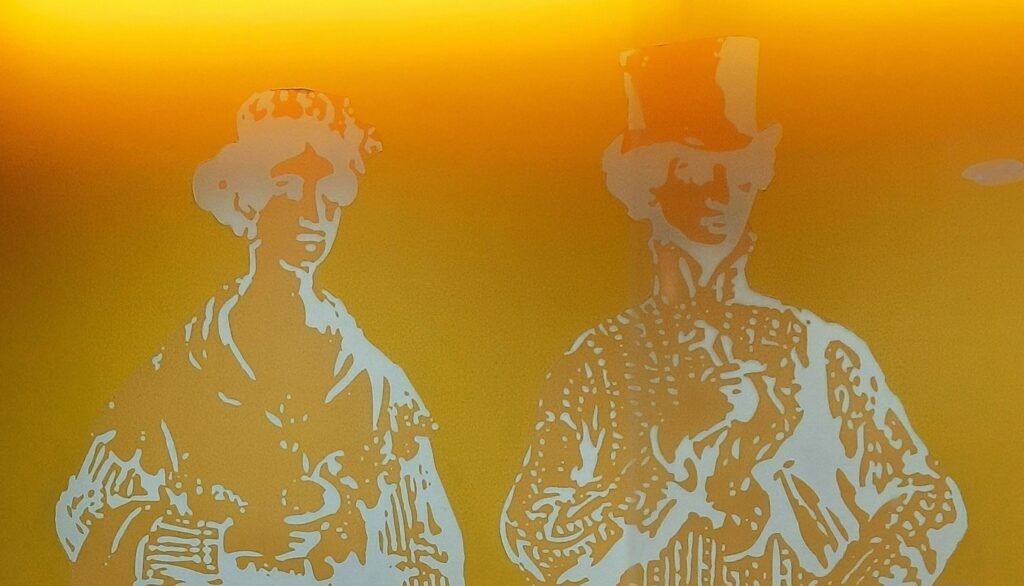

The painting reminds me of clothing and fabric. Interestingly, 2 years after Garcellano painted this, she went full-out glamour in her works entitled “19th Century Redux III & IV” for the year-end Finale group show in 2022. In her own words, she has even reflected on this transition from 2020 to 2022 as something like an “induced hyper speed” (try to recall how much the world changed from 2020 to 2022 and let that sink in). No fetishizing or romanticizing is present in these works of Garcellano. I find them to be highly rational works, with the emotional energy focused beautifully on the figurative elements. They are sartorial in the best sense of the word.

19th Century Redux III & IV by Lyra Garcellano. Courtesy of Finale Art File.

With this sartorial viewpoint, it is only natural to turn towards mercantile values, pragmatism, and the entrepreneurial spirit that all together are sources of motivation in our daily lives. Why, even BPI has Tipos del Pais references! And this is not some Lalaland fantasy either, because as we ponder on the ideals of prestige and hierarchy in our collective imagination, these ideals are interwoven to serve political and “nationalist” agendas. These are concrete aspirations.

We need that reassurance or reminder of an ordered and civilized state. Yet the discernment to filter or draw nourishing energy from the illusions of our own constructed realities is another story. Similar to Canaletto who elevated idealizing landscapes into a myth that lives to this day, colors cannot be constrained by the frame that surrounds them. •

Joshua Alexander “Joey” Manalo is a classically trained pianist having navigated through scores on his own from the age of six, eventually taking private lessons and graduating cum laude in 2009 at Rutgers University with a Minor in Music and a Major in Psychology. He was then taken under the wing of pianist Jovianney Emmanuel Cruz and had his orchestral debut in February 2011 in Insular Life Theater under the baton of conductor Marlon Daniel. Joey currently manages Outlooke Pointe Foundation’s projects and art collection. The non-profit organization was founded by his father, Jesulito Manalo in 2007 in a bid to support emerging artists and foster creative collaborations, “with the vision of utilizing art as a tool for nation-building.”