Introduction Patrick Kasingsing and Gabrielle de la Cruz

Interview Gabrielle de la Cruz

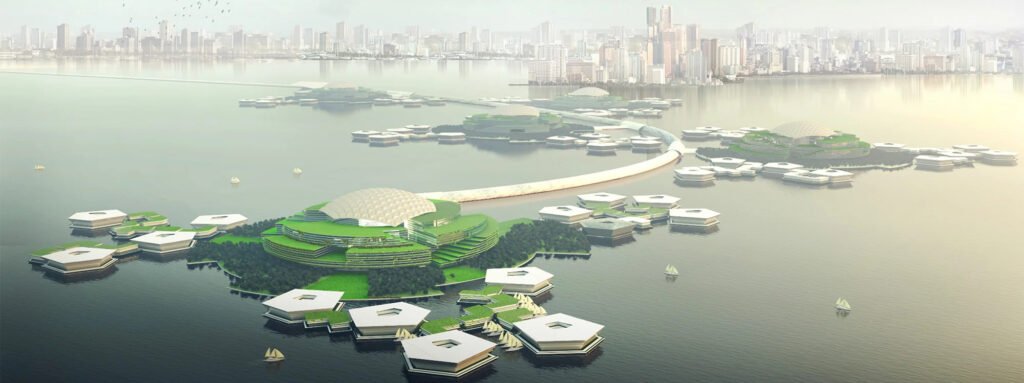

Images Joel Luna Planning and Design

The year that was

Merriam-Webster’s “gaslighting,” Messi’s ‘crowning’ at the FIFA World Cup, the rise (and imminent fall?) of Musk-era Twitter, the monumental departures of Queen E and Pélé, and the continuing turbulence in Ukraine and Iran… 2022 sure was a memorable ride, for better or worse.

On local shores, 2022 hosted a significant election, one whose outcome is still the subject of myriad Facebook groups, heated debates, and countless memes. It also broke records for dollar-to-peso exchange rates and the price of the humble onion, and paved the way for the return of concerts, exhibits, and other public gatherings (along with the pre-pandemic traffic situation, unfortunately).

YES 2023

It is in the spirit of tenacious optimism that we at Kanto look back at 2022, parsing through the past year’s opportunities and challenges to find lessons and insights that can help arm us for the year ahead.

Welcome to Kanto’s first Year End Special or YES 2023—a collection of conversations with creative professionals who help us unpack a year’s worth of lessons and insights, along with their forecasts and wishlists for the year ahead.

A conversation with urban planner, Joel Luna

We kick off the series from a macro, urban planning perspective with urban planner Joel Luna of Joel Luna Planning and Design. He is the former Chief Architect, Vice President, and Head of Ayala Land, Inc.’s Innovation and Design Group. His firm JLPD specializes in the planning of large-scale, mixed-use townships, community planning, tourism estates, and urban place-making. Notable projects include their Panglao Bay masterplan, campus master planning for Holy Angel University, and their alternative urban future concept, Manila 2060.

Hello, Joel! Thank you for your time. Can you give us an overview of how your 2022 has been?

2022 has been significantly busier for us at JLPD compared to the past 2 years and this is simply a reflection of the upswing in overall economic activity as we rebound from the slowdown during the pandemic. As we close the year, we find ourselves scrambling to finish our deliverables while we also gear up for next year’s activities. We all wanted to take a break during the Christmas holidays, so that became our motivation for the home stretch.

You mentioned slowing down due to the pandemic and scrambling to finish deliverables. What were some of your most challenging projects this year?

We worked on a couple of projects that were particularly engaging. One was an urban redevelopment project of an existing commercial district that was significantly affected by the pandemic lockdowns. Our whole team had to put our minds together and employed observational techniques to identify what was really going on and from there, propose solutions to rejuvenate the place. Another is for a sensitive coastal development project where we had to propose some light-handed solutions to preserve the surrounding mangroves. We proposed interesting ideas such as floating architecture and floating farms and bioclimatic architecture. Projects that challenge our typical ways of thinking are always exciting for us.

The pandemic undoubtedly affected firm operations and project delivery. What operational changes and pivots were implemented? With the gradual improvement of our pandemic situation, what does your post-pandemic work setup look like?

The biggest learning probably has more to do with the operations of our firm. We are on a hybrid setup with most of the team members still largely working from home and coming for in-person meetings only as needed. We have come to adapt to this flexible mode of working. And although nothing beats the level of collaboration and spontaneous idea exchange that comes from being complete and together in the workplace, flexibility does offer a different form of productivity, especially once you consider the cost of time, stress, and anxiety lost during commutes. Important learning, therefore, revolves around the whole notion of productivity.

We have reached a point where productivity is no longer bound by time or space (creativity never was, to begin with). The size of our firm and the nature of our work allows us this flexibility. The challenge is how to facilitate engagement, coordination, mentoring, and collaboration under this flexible system.

From your perspective, how much did the hybrid work setup affect cities? What does this mean for urban planning in general?

When the economy re-opened in 2022, there were a lot of transformations in the workplace that persisted post-pandemic—hybrid working being one of them. Many firms have adopted a full work-from-home or flexible work arrangement. This has many positive implications such as the potential to reduce or eliminate commutes, and lower pollution, and traffic congestion levels. It also allowed for decentralized activities which potentially disperses economic activity to other areas, activating suburban areas. The whole concept of productivity has been redefined and is now less place-based. This has profound implications for cities. On the other hand, the decoupling of work from the traditional office could have repercussions on property development.

The bright side here is that it could allow for a rethinking of the office typology and of the purpose of central business districts. Many CBDs now function more like social districts. The challenge for the property sector is how to create products and spaces that can harness and reinforce this evolution.

Apart from the adjustments in the office typology, what significant pandemic-driven changes in the urban planning industry did you observe?

The COVID pandemic prompted many practitioners to take more seriously the issues of healthy environments, active mobility, spatial justice, resource and energy scarcity, and open space provision in the built environment. I have observed that many urban planners have taken several advocacies, supporting different causes such as active mobility or regenerative development. I’ve also noticed an increasing interest among young designers and even students in urban issues of the city with a constructive form of dissatisfaction with the status quo—a drive towards creating better places for people. I find hope in these observations.

Urban planning was once seen as an esoteric profession practiced only by the intellectual elite. Today, more people voice their opinion about the built environment, how Metro Manila is currently planned, and how it can be planned better.

Part of the clamor for replanning Metro Manila and the Philippines, in general, is the addition of proper bike lanes, green urban spaces, and lively community hubs. What are your thoughts on this? Do you think such suggestions must be immediately implemented moving forward? What factors should be considered when integrating these elements into existing urban spaces?

The pandemic revealed a lot of what’s deficient in our urban areas. We realized that we don’t have resilient mobility systems, supply chain systems, and food systems. We also saw the impact of not having enough open spaces and outdoor areas in our cities. Our old paradigms were restrictive, inflexible, and ultimately fragile in the midst of a crisis. It also showed how uneven our physical realm is, skewed towards those who have the means.

Fortunately, many communities adapted to the crisis by setting up community gardens, by setting up small food and delivery systems, creating community pantries to help those in need, by shifting to cycling as means of commuting. These ground-up interventions show possible directions of how we should be planning our cities. We need to view these small interventions as insights to form more permanent solutions for mobility, land use, and open spaces for our cities.

Across all the urban planning propositions and advocacies you’ve come across this 2022, was there a particular one that stood out for you?

I think that the thrust for more inclusive mobility stood out as a major eye-opener for the past two years and continues to gain momentum. Many mobility advocates have voiced their opposition to car-centric infrastructure (most notably PAREX). The groundswell behind the cause for more people-centric mobility shows that we have reached a tipping point of awareness, driven by a strong dissatisfaction with the status quo and top-down solutions. It also shows the willingness of people to participate, contribute and voice their opinions on relevant issues.

For me, it reflects an overall shift in collective mindset that emerged during the election period, the community pantry phenomenon, and the mobility advocacies of different sectors. These are resources that can be harnessed to improve our urban environment and society in general.

We cannot deny that working towards these developments comes with trial and error. Have you observed any worrying developments recently? What would you say is the biggest challenge for the urban planning profession at the moment?

I think the biggest risk to urban planning or society at present is the tendency to revert to the old normal. Prior to the pandemic, the prevailing view is that bigger is better—we had mega structures, large townships, and big malls. The tempering effects of the crisis showed the value of scaling down.

Emerging from the pandemic, it is very tempting to follow old patterns of thinking and pursue old goals, revert to old behaviors disregarding whatever lessons we learned from the crisis. For instance, I was disheartened to see that some of the parklets that we had on some streets in the CBD have reverted into parking spaces. This, to me, is a regression to the old norm of being more car-centric rather than creating more people-centric places in the city.

We faced an unprecedented crisis during COVID which required unprecedented solutions. We continue to face novel challenges in the coming years. Our old paradigms simply won’t cut it anymore.

You say that old paradigms must be left behind. What new paradigms do you wish to see in 2023? What are your hopes for urban planning in the coming year?

I hope urban planning can help answer some of the big questions of our times—climate change, bio-habitat depletion, resource scarcity, and inequity. I hope that some nexus approach that can simultaneously address these issues could be found and manifest itself in the way we plan our cities. I am particularly intrigued by the potential of our marine environment to solve our problems of energy, food, and resource scarcity, as well as our problems of carbon sequestration.

Harnessing the oceans as future habitats and a way to heal ecological damage. The scope of planning has largely been terrestrial, treating the ocean simply as a sink for our waste. Floating cities may not happen next year, but some pioneering minds have been exploring this idea for quite some time now. And with climate change already upon us, we need drastic measures to adapt while we try to reverse carbon emissions.

More immediately, I hope that there will be a stronger focus on inclusive mobility in our cities. We need to have a system-wide view of mobility that simultaneously address land use and accessibility, and mass mobility. We have already seen how a narrow view that infrastructure investments for private vehicular mobility ignore the needs of the vast majority, disadvantaging everyone. I hope our policymakers and the property industry can prioritize this in future developments.

How does your firm plan to contribute to the development of the urban planning sector head-on? Can you let us in on some of JLPD’s plans for 2023?

The coming year seems to look very exciting as opportunities open up on the work front. Many of the projects we were working on were recently launched and we’re looking forward to a few others moving to the implementation stage. I was also quite fascinated by the way AI has been evolving lately and was intrigued by AI artwork. I started exploring how AI-generated illustrations can augment our own designs for our projects. It’s quite fascinating to use them.

We’ve also been introducing regenerative features and nature-based solutions in many of our large-scale projects and it is good to see that there is interest in these approaches among our clients. What is most exciting for me is our expanding network of strategic allies. We have collaborated with Archiglobal since we started JLPD and more recently, we have broadened our strategic partnership with Clarq Landscape and some individual consultants and we are looking forward to pursuing more projects jointly, bringing to the table our collective and individual skills.

Wow, you and your team seem to have done a lot of work in 2022 and you already have plans set moving forward. Were you able to take breaks? How did you spend your downtime? Did you discover new personal hobbies or talents?

I still spent most of my time indoors and I think I spend most of my time reading. Reading has always been a hobby and recently I’ve been drawn to reading about economics, financial history, some futurists’ theories, and of course books on planning.

The normalization of activities allowed me to go on a few side trips though, visiting some islands and trekking some properties—not necessarily downtime, but after spending more than 2 years cooped up indoors, being out among trees and hills was literally a breath of fresh air. We’ve also had a few in-person casual activities with my team and a few get-together activities with old friends. Those were fun.

Lastly, if you were to look back on everything that you did this 2022, what would you consider your proudest achievement? Why this in particular?

One upside of being an architect is that we can see and experience places in our minds long before anyone else does. And one of our highest forms of fulfillment is to see these images actually built and used by people. One project that I had the honor of working on during my last years as head of Innovation and Design in Ayala Land was Tower Two at Ayala Triangle. This year, I had the privilege of seeing the building completed. It took nearly a decade since we began conceptualizing the project.

No project is ever easy and it takes a lot of dedicated people and strong leadership to complete it. Seeing it stand now makes me proud of the talented people I had the honor of working with and who had the perseverance to see it through.

The flip side to this is that oftentimes, our boldest ideas are the ones that do not reach implementation. These are the discarded schemes, unapproved concepts, and layers of ideas that remain simply as visions in our minds or as plans awaiting implementation. We are proud of these too. There is a lot of value in the thinking that goes behind any project whether these are implemented or not. •

Gabrielle de la Cruz started writing about architecture and design in 2019. She previously wrote for BluPrint magazine and was trained under the leadership of then Editor-in-Chief Judith Torres and then Creative Director Patrick Kasingsing. Read more of her work here and follow her on Instagram @gabbie.delacruz.