Interview Patrick Kasingsing

Images Dar & Wagh

Hello Ranjit and Amber! Welcome to Kanto! You both came from illustrious architectural practices: Kerry Hill and WOHA. What would you say are valuable insights, practices, or sensitivities from where you came from that you took with you to Dar & Wagh?

Ranjit Wagh and Amber Dar Wagh, co-founders of Dar & Wagh: We were indeed very lucky to have had a long period of learning and association with Kerry Hill and WOHA. Both places are headed by a genuinely great bunch of people making them wonderful places to be. Every person in the studio enjoys conditions that enable us to push out our best work, making possible an unflinching focus on practice.

To maintain a diversity of people and projects was fundamental to both firms. This allowed ideas and experiences to meld, creating unique genius loci complementary to Singapore where the practices are based. Large commissions mean large teams. We learned to keep one’s ego aside and work together with the sole intent of bettering the project, always keeping the client’s interest at the top.

But our most important learning was that― ‘if you just focus on the architecture everything else comes along for the ride’.

As Indian architects schooled “in the modernist architectural tradition of Ahmedabad,” was your modernist-leaning training a boon or bane when you entered practices outside of India? How would you describe India’s system of architectural education?

We studied at CEPT, which is Pritzker Laureate Balkrishna Doshi’s school in Ahmedabad. It was founded in the early 60s, a time of great architectural and social churning in India.

Chandigarh was newly-minted. Corbusier had finished four commissions in Ahmedabad and Doshi had recently started his practice. Then came Louis Kahn’s Management Institute and the works of their Indian protégés Anant Raje, Achyut Kanvinde, and Hasmukh Patel among many others.

Had Frank Lloyd Wright’s Calico Mills project been built, Ahmedabad would have the rare distinction of being the only city in the world to have built works by all three Modern masters. It was exactly in this heady modern cocktail at Ahmedabad that young, 17-year-old aspiring architects were thrown in.

What works in a modernist school is a clear focus on the fundamentals of architecture―space, order, structure, light, and form. The rigor is absolute. Our university was also small, which meant it was a close-knit group of people completely immersed in learning. These strong fundamentals helped us transition quite easily when we joined practices in Singapore.

Like most developing countries, and indeed most parts of the world, there is a decentralization of education and a massive proliferation of new places of learning. A number of them, like India, are still trying to find their feet. It’s a long climb.

It is always a challenge to strike out on your own; can you recount to us what convinced you both to start Dar & Wagh in 2015?

Quite frankly, it was a family matter that brought us back to India. We toyed with the idea of working for someone in Pune before starting off. But it was Richard and Mun Summ (of WOHA) who strongly advised us against doing so and told us to take that leap of faith. Kerry and Justin (of Kerry Hill Architects) were equally supportive of the decision. If they believed in us, what excuse did we have?

What would you say were the most pressing challenges you encountered as a young practice?

It was the reverse culture shock that took us off guard the most―something we didn’t expect as we were simply ‘coming back home.’ But home had changed.

We had also built little in India till then and were returning to Pune after a gap of 20 years. To add to this, we had two very young children who deservedly needed time and attention. This was in addition to the usual teething problems for any new practice. A triple whammy!

Was it easy or hard to locate new clients?

After a few months in India, once we settled down a bit, we took our portfolio and met as many people as we could to show them what we could do. Luckily for us, our extensive experience convinced some clients to give us a chance. From that point on, it was just hard work.

Till now, we’ve been consciously under the radar on social media and intentionally so. People often ask us how we get commissions without a website. Almost all our work has come through referrals and repeat clients. So hopefully we are doing something right.

Any memorable anecdotes to share about the firm’s early days?

We were in Mumbai in 2015, showing our work to one prospective client. As luck would have it, WOHA was having a meeting next door with the same client for another project. Of course, they recommended us and we had our first project―a community club.

If you could sum up your firm’s spatial approach in a dictum or a mantra, what would it be?

It would most definitely be this: To bring balance and a sense of rest to any space.

I know it’s hard to choose favorites but what project from your current body of work would you say embodies this belief the most? How does it do so?

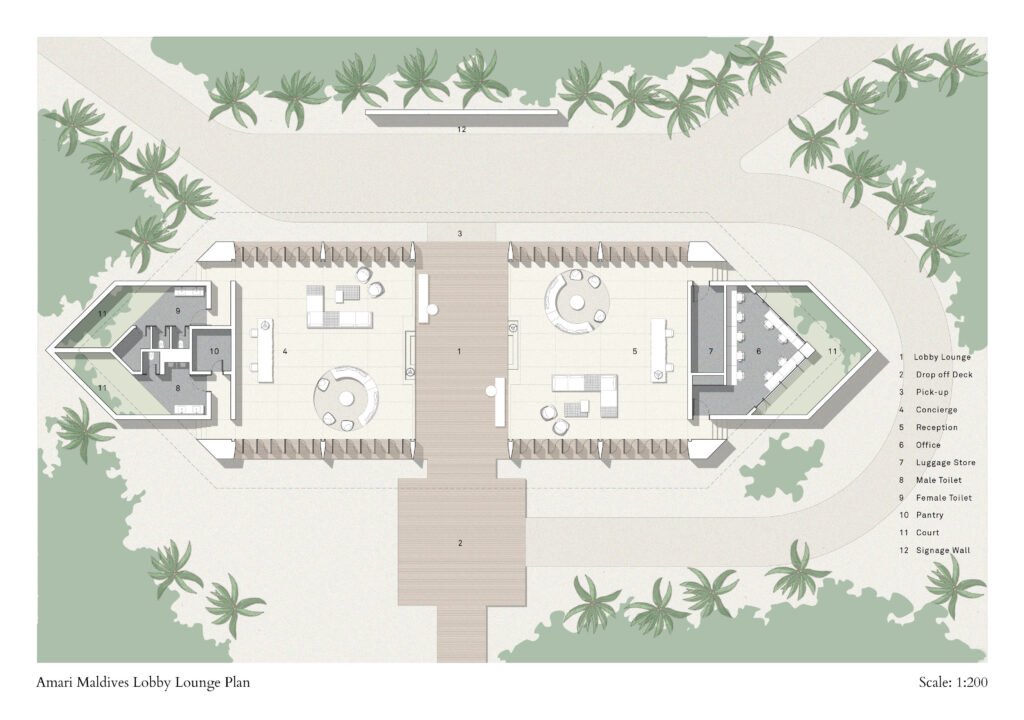

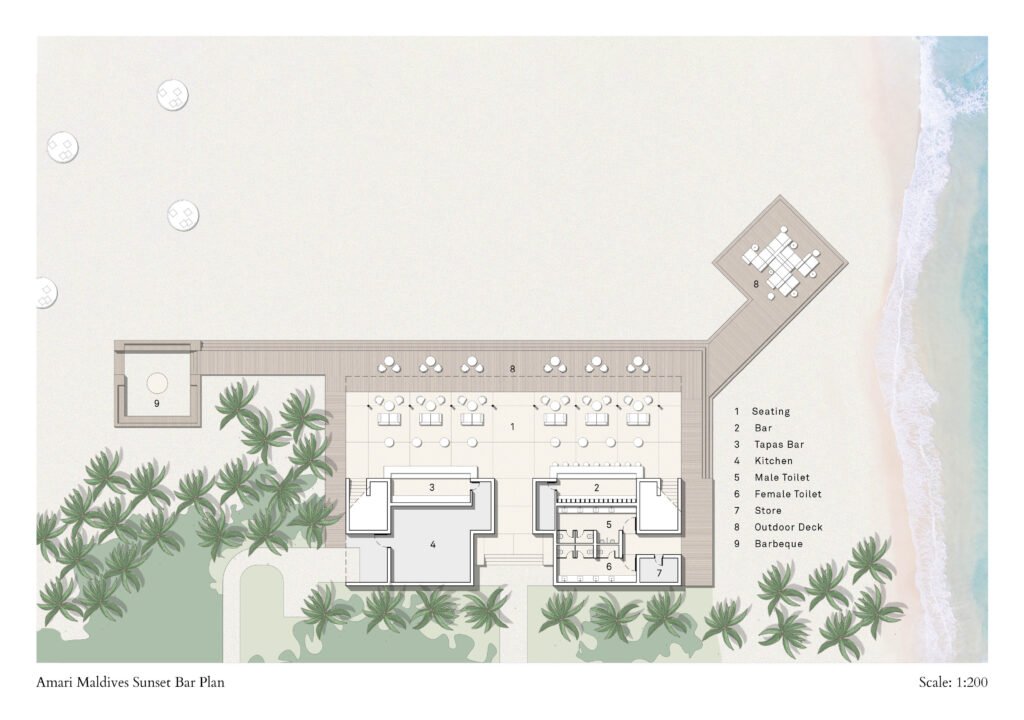

The one on our drawing board! On a serious note, the Lobby and the Sunset Bar, two buildings at a new resort in the Maldives would be good examples. Both buildings embody deceptive simplicity and effortlessness. This is achieved by an intentionally subtractive process of removing everything unnecessary from the architecture. By bringing balance and rest to spaces, the buildings recede into the background simply becoming facilitators for guests to enjoy their holidays in the stunning Maldivian landscape.

You mostly design in tropical locales, having done so for decades working for Kerry Hill and WOHA; what elements or characteristics would you consider to be fundamental to tropical architecture?

Tropical climate is reasonably salubrious most of the time with minimal climate control strategies and wind helping to bring comfort to inhabitants. Buildings need to be full of spaces that allow the breeze to flow. Rooms in the European sense don’t really exist. So the architecture is ambiguous about whether a place is open or closed. It’s all about verandas and their connection to nature.

What do you think are some of the present issues or misconceptions this architectural approach is riddled with?

Like a lot of architecture, there is a tendency to see tropical buildings and their architectural expression merely as a design trend.

For example, Kerry’s buildings are extremely elegant and photogenic, but that’s arguably an unintended consequence of a deeper architectural search. Kerry himself always said that his buildings are better experienced than photographed. That’s because while he was a master of order, space, light, and materials, his exceptional talent was in his ability to create buildings that could evoke emotions; the way the sun came in, how the view opened, where the eye moved…These were carefully choreographed experiences that were impossible to capture through a camera.

Tropical architecture, like all good architecture, is rooted to place, and its expression is incidental. Unfortunately, it’s the expression that often gets the focus and we get inquiries asking us to build tropical open houses in hot and dry, desert-like climates. It makes little sense to do so.

Let’s talk about your dream commission. What would this project be and why so?

A primary school or a health center in rural India.

We truly believe that architecture can empower. And building something like this will have a direct and positive impact where it matters most. The only way architects can serve society is by building well. And commissions like these, perhaps unfettered by egos and personal agendas, are places where the true beauty and essentiality of architecture lie.

Jumping off from that train of thought regarding beauty, should all architecture be beautiful?

Absolutely, otherwise, it would be mere construction. Corbusier answers this wonderfully in Towards a New Architecture. But we think the deeper question is what makes architecture beautiful?

For us, if every design decision while making a building has at least two reasons to be and at the same time provides a harmonious and balanced solution, then it passes the test. The beauty becomes innate.

India is slowly gaining recognition as a wellspring of precocious architectural talent as evidenced by the awarding of the Pritzker to Balkrishna Doshi and the rising stature of Indian practices within the global design conversation. What quality or sensitivity does the Indian spatial approach embody which is now finding appreciation and an audience globally?

The Indian subcontinent has a very unique and special culture. You can see it in the languages, the clothes, the food, and the festivals. There is a messy vitality about the place and the attitude to space-making kind of mirrors this.

To borrow from Kurula Varkey’s thoughts: “It is one of ‘layering’ from outside to inside. In the urban context, this coming together of the spatiality of diverse elements create conjunctions, and overlaps creating multiple layers. The result is a great deal of informality―the axis always shifts, spaces move diagonally, the route shifts. Each has its own law, but the total is coming together of diverse parts within an ideational unity.”

This is very different from the western ideas of clarification and abstraction. So unless we de-school ourselves from the western notions of beauty, it’s impossible to appreciate India. Unfortunately, the intellectual agendas of architecture are very Eurocentric. Europe after all has been at the forefront of the world for close to 400 years.

But to see India, or for that matter, any developing country through those lenses is a disservice. Until we consciously remove those lenses, we can never truly appreciate Indian architecture for what it is. When Doshi won the Pritzker, Reuters called him ‘India’s architect for the poor’. This was simply because they were unable to reconcile why the jury chose his work when it didn’t fall into any of the west’s accepted notions of success or beauty.

In the face of globalization, is there still a need to develop a culturally-distinct architectural style or aesthetic?

Yes, but this should come naturally as a response to the project needs and constraints rather than an ideological architectural imposition. Only then will it be grounded and valid.

What do you think is the most pressing challenge the field of architecture has to contend with today? How is your firm addressing this challenge?

Climate change is undoubtedly the single biggest challenge facing humanity. The only way we can step up to this is by building intelligently. First, we try and optimize whatever needs to be built. To build less is a good thing. There is also a conscious engagement with clients and contractors to select materials, practices, and designs that offer environmentally suitable solutions.

Here’s a fun question: if you can pick any architect, dead or alive to design your house, who would you pick?

Would have to be Carlo Scarpa or Rick Joy!

Let’s now close this interview with some advice for aspiring architects: what would you say are important skills or traits an aspiring designer should hone to be able to create effective and beautiful spaces?

Listen to the client, keep your ego aside and approach every design with a clarity of mind and purity of heart. •

2 Responses